Today I am returning to an artist I first featured almost twenty months ago. The artist in question is Andrew Wyeth and in My Daily Art Display of January 3rd 2011 I looked at his famous work entitled Christina’s World. It is an extremely poignant painting and one which will always linger in my memory. I do recommend you go and have a look at it and see what you think. My featured painting today is a beautiful portrait which Andrew Wyeth completed in 1966 and is entitled Maga’s Daughter. The reason for the title will become apparent when you read the life story of Andrew and his wife Betsy.

Andrew Wyeth was born in 1917 in the town of Chadds Ford, Delaware County Pennsylvania. His mother was Carolyn Brenneman Wyeth (née Bockius), a lady from Wilmington. His father was Newell Convers (N.C.)Wyeth, an artist and one of America’s greatest illustrators. N.C. Wyeth had moved from Massachusetts as a young man to study with the illustrator Howard Pyle in Chadds Ford and it was here in 1908 that he and Carolyn married. He then built his home and studio on an eighteen acre homestead close to the site of the Brandywine battlefield, where in 1777 the Continental army led by George Washington fought the British army in the American Revolutionary War. The couple went on to have three daughters and two sons of which, Andrew was the youngest. All the children were extremely talented. The eldest child, Henrietta is considered by many art scholars to be one of the great women painters of the 20th century. Carolyn Wyeth, the second daughter was also an artist whilst the youngest daughter, Ann, was a talented musician. Andrew Wyeth’s elder brother, Nathaniel, was a mechanical engineer and inventor.

Andrew Wyeth’s father although wanting to devote his time to painting had to, for financial reasons, concentrate on his work as an illustrator. It was a well paid profession and the family lived a comfortable lifestyle. As a child, Andrew never kept well, one illness followed another and consequently he spent a lot of time at home and his father had to provide him with home tutoring. There was a marked difference between father and son. His father was a big man and had boundless energy which was in marked contrast to his frail and delicate son. Later in life Andrew Wyeth remembered those days closeted at home with his father. He wrote:

“…Pa kept me almost in a jail,” Wyeth recalled, “just kept me to himself in my own world, and he wouldn’t let anyone in on it. I was almost made to stay in Sherwood Forest with Maid Marion and the rebels…”

Before Andrew Wyeth had reached his teenage years his father had achieved celebrity status as an illustrator having illustrated Robert Louis Stevenson’s famous book, Treasure Island. Following on from this success he illustrated other famous novels such as James Fenimore Cooper’s Last of the Mohicans and Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe. Andrew Wyeth was taught art by his father, who inspired his son’s love of rural landscapes, sense of romance, and instilled in him a feeling for the Wyeth family artistic traditions. From an early age, the youngster soon began to enjoy drawing and with his father’s guidance, he quickly mastered figure study and watercolour techniques. Andrew soon became fascinated by art history and loved to look at works by not only the Renaissance Masters but native born American artists, such as Winslow Homer. In 1937, when he was twenty years of age, Andrew had his first one-man exhibition of watercolours at the Macbeth Gallery in New York City. It was a resounding success and all the works exhibited were sold. It was now that he was certain in his own mind that a career as an artist was all he wanted. This immediate success which he achieved did not reassure him as like many talented people he was exceedingly self-critical. He was irritated by some of his work believing it to be too facile.

It was in 1939 that Andrew Wyeth met Betsy Merle James. Betsy James was born in the village of East Aurora in New York State in 1922. Her father, Merle James, a trained artist, worked as a printer for the newspaper, Buffalo Courier-Express. Her mother was Elizabeth “Maga” Browning (hence the title of today’s featured painting). Betsy grew up as the youngest of three girls. In the 1930’s the family spent their summers with their friends on Bird Point, a promontory jutting out into the Atlantic Ocean, close to the town of Cushing, Maine. The next door neighbours were Alvaro Olson, a blueberry farmer and his sister Christina . This was the Christina of Wyeth’s famous painting Christina’s World. As a young girl Betsy became great friends with Christina. In 1939, on Andrew Wyeth’s twenty-second birthday, while spending the summer in Maine, the seventeen year old Betsy James and the twenty-two year old Andrew Wyeth met. At this initial meeting Betsy James took Andrew to Cushing to introduce him to her long-time friend Christina, who had been crippled by polio in childhood. Strangely, at this first meeting, it was not Christina who made the greatest impression on Andrew Wyeth but the weather-beaten, three-story, steep-roofed, clapboard house, built on a coastal promontory which was her home. However later Christina and Andrew became good friends and she featured in many of his paintings including three beautiful portraits entitled, Christina Olson (1947), Miss Olson (1952), and Anna Christina (1967). Christina even allowed him to convert one of the rooms in their farmhouse into a studio.

Andrew and Betsy dated all that summer and in the fall, when Betsy went off to the Colby Junior College in New Hampshire, they faithfully corresponded with each other. They were in love and the following year they married and set up home in an old schoolhouse which lay on the Wyeth family land. Although Betsy was not an artist, Andrew continually sought her judgement on his work. Sales of Andrew Wyeth’s works of art grew steadily and Betsy managed the business side leaving her husband to concentrate solely on his art. Betsy had a strong character and exerted almost as much influence on her husband as his father. In the early days of her marriage, she believed that she had to battle with Andrew’s father to gain her husband’s attention. She once commented to Richard Meryman, Andrew Wyeth’s biographer, on her battle with her father-in-law:

“I was part of a conspiracy to dethrone the king — the usurper of the throne. And I did. I put Andrew on the throne…”

In 1943 the couple had their first child, a son Nicholas. A second son, James followed three years later and would become a renowned artist in his own right. Eighteen years after the couple married and settled in to life in the school house, they moved and bought an old 18th century gristmill on the banks of the Brandywine River in Pennsylvania. Whilst her husband spent days on end painting, Betsy set about restoring the old mill, converting it into a home and a studio.

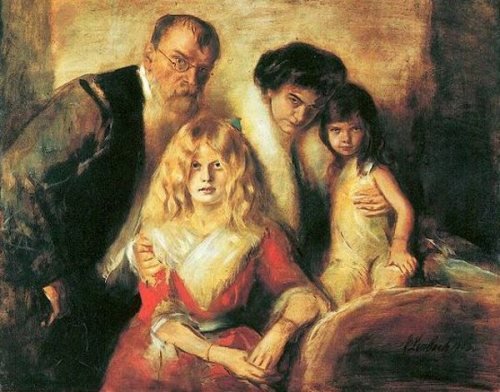

The featured painting today is Maga’s Daughter by Andrew Wyeth, which he completed in 1966. It is a portrait of his beloved wife Betsy, whose mother was Elizabeth “Maga” James . She posed in a three-quarter view. She stands erect. Her bearing is one of dignified pride as she averts her eyes away from the viewer. Atop her head is an antique riding hat with its drawstrings dangling freely on either side of her face, almost if they were acting as a frame of a picture. She wears a drab-coloured, high collared dress which almost blends in with the slightly lighter coloured background. There is a faint flush of colour to her cheeks and a smile is forming on her lips. What beautiful eyes she has, lit by the unseen light source to the left of the painting.

What was Andrew Wyeth thinking as he painted this portrait? Actually we know, for he told us:

“…It’s my wife, Betsy. I had worked a long time on this and knew it wasn’t working. At the time I was on board of trustees of the Smithsonian Institution – quite prestigious. But Betsy didn’t like it, telling me that my work would suffer because of all these boards. I left for Washington one morning, and Betsy got furious, really flew into a rage. All the way down I kept thinking of that colour rising up high into her cheeks. I knew I had captured her. The colour of those cheeks under her coal black hair and that hat gives the portrait a real edge. Really caught her. It’s more than a picture of a lovely looking woman. It’s blood rushing up. Portraits live or not on such fine lines! What makes this, is that odd, flat Quaker hat and the wonderful teardrop ribbons and those flushed cheeks. She could be a Quaker girl who’s just come in from riding… ”

On January 16, 2009, Andrew Wyeth died in his sleep at his home in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, after a brief illness. He was 91 years old. Andrew and Betsy Wyeth had been married sixty nine years