In my previous blog I concentrated on the portraiture of Marie Bashkirtseff but she will probably be remembered best for other genres

One painting by Marie Bashkirtseff which came about during her time at the Académie Julian was one commissioned by the founder of the establishment, Rodolphe Julian. He asked her to paint a canvas depicting the artists at work in his academy. The finished canvas was entitled L’Atelier Julian and is now looked upon as one of Bashkirtseff’s finest works. Initially Marie was not impressed by the commission but could see the benefit for herself, writing in her diary:

“…As for the subject, it does not fascinate me, but it may be very amusing, and then Julian is so taken with it, and so convinced… A woman’s studio has never been painted. Besides, as it would be an advertisement for him, he would do all in the world to give me the wonderful notoriety he speaks about…”

The painting portrays the light and airy studio at the Académie Julian where Bashkirtseff and her fellow students would work. L’atelier Julian is a quite large oil on canvas work measuring 154 x 186cms and is currently housed in the Dnepropetrovsk State Art Museum. It is a fascinating work featuring sixteen students all taking part in a life-drawing session. The studio looks well organised, although small in size, but that maybe due to the number of people crammed into the room. As an observer, we firstly focus on the woman seated at the centre of the work. She wears a bright blue dress. In her hands are a small brush and a maulstick. She is working on a painting of the young nude model, who is holding a staff whilst standing on the raised dais so that he can be seen clearly by all the female students. If we look past this lady we see one of her colleagues staring out at us. Maybe someone is entering the room to join this artistic group. Our eyes now leave the lady in blue and we start to scan the rest of the room. It is a hubbub of activity. Some of the females are concentrating intently on their canvases whilst others partake in chit-chat. The two females in the foreground, one seated, one standing, engage in conversation. The lady standing rests her hand on a wine-coloured velvet drape which has been laid over the back of the chair. Look at the drape. See how Bashkirtsteff has showcased her artistic ability in the way she has depicted the elaborate folds of the material. Many artists in the past and in the present time like to show off their artistic skills in this way. This large and multi-faceted work was exhibited to great acclaim at the 1881 Salon.

Following a visit to Russia in 1882 to visit her relatives she returned to Paris. She had not been feeling well and decided to visit her doctor. In Dormer Creston’s 1937 biography on the artist entitled Fountains of Youth – The Life of Marie Bashkirtseff, he quoted her diary entries:

“…At the doctor’s. For the first time, I had the courage to say: Monsieur, I am becoming deaf. It can be borne, but there will be a veil between me and the rest of the world…”

Later that year her health deteriorated further and she noted in her dairy after visiting the physician that the news was not good:

“…I am consumptive, he told me so to-day…”

Despite her failing health she carried on with her art. She punished herself by working long hours almost as if she realised her time was almost up and none should be wasted. It was in 1882 that she met the French painter Jules Bastien-Lepage. He was ten years older than Marie but he became her confidante and mentor and her greatest inspiration. It has often been mooted that the two became very close romantically. He persuaded her to look beyond her wealthy lifestyle and observe and depict in her paintings those who were less financially fortunate than herself. She listened to Bastien-Lepage and soon the subjects of her work changed. Her works soon depicted the lower classes and street scenes. This was such a turn-around for a young woman who had only known the life of affluence.

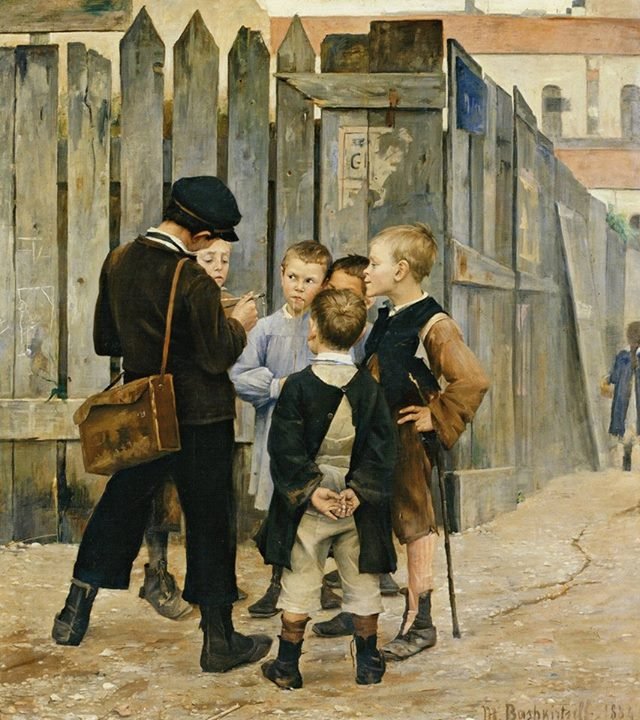

One of her best loved paintings featuring the “real world” is entitled The Meeting which she completed in 1884 and was exhibited at that year’s Salon. It is now housed at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. It was an enormous success, both with the press and public alike. However, much to Bashkirtseff’s annoyance, her painting was not awarded a medal. In her diary she wrote of her frustration and disappointment:

“…I am exceedingly indignant because, after all, works that are really rather poor have received prizes…..There is nothing more to be done. I am a worthless creature, humiliated, finished…”

Marie believed that being awarded a medal by the Salon jurists would help to immortalise her and that, to her, was of the utmost importance as, at this time, she knew her life was coming to an end. She desperately did not want to die before her artistic talent was recognised. She dreaded being forgotten.

In this next work, Marie Bashkirtseff copies the Naturalist style of her friend and mentor, Jules Bastien-Lepage. Lepage’s naturalism focused mainly on the countryside but Bashkirtseff decided to follow his style of naturalism or realism but concentrate on an urban setting. In some ways the work is a genre scene, a depiction of everyday life. Before us are six young boys, who stand in a circle fascinated with what the tallest boy has in his hand, although it is not visible to us. Whatever it is, it has them deep in discussion. Some still wear their school smocks. The shabbiness of their clothes and shoes marks them as coming from poor working-class families and the setting is a run-down working class area. We see, behind the group of boys, the old wooden fence with the graffiti and the torn posters all inferring that the setting is one of poverty.

Bashkirtseff’s choice of depicting working-class schoolchildren in this painting may have come about as it was the subject of schooling which had become a great topic of conversation in the early 1880’s with Jules Ferry, a member of the French government at the time, establishing the law that saw the arrival of free, compulsory, secular education. However other art critics would have us believe that the depiction of the boys was simply a bourgeois stereotype that people like Bashkirtseff would adopt. Again some people wanted to look for a message in the painting, a message that may only be there in their eyes. The feminists pointed to the fact that the group are all males and further suggest that the young girl walking away alone is symbolic of the feminist movement and their desire for better integration in society. In the book, Overcoming All Obstacles: The Women of the Académie Julian by Gabriel Weisberg and Jane Becker, the writers wrote about the painting and its lack of recognition by the Salon jurists:

“…While painters at the Salon designated her for a medal, the jury passed on her submission. The public complained. While Robert-Fleury was encouraging her to include passages of draped figures (to show off her virtuosity in that skill), Marie refused, not finding drapery fitting to her modern street boys. Again the critics noted her sincerity of execution, freshness of facture, and realism in taking up the subject. While the work did not receive a medal, it was bought by the state, and several engravings and lithographs were made after it…”

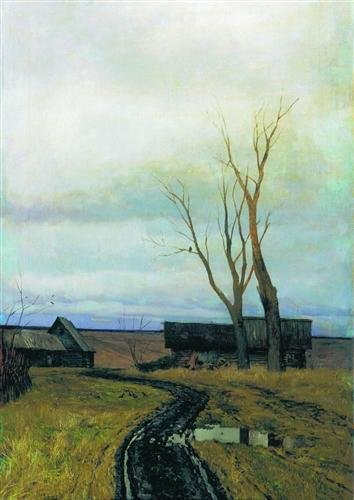

Although I stated earlier that Bashkirtseff wanted to focus on urban portrayals, my next offering of her work is a beautiful painting entitled Autumn, which moves towards a landscape work. The setting is a rutted tree-lined road which runs parallel to the river. Through the trees we see an arched stone bridge which straddles the waterway. The time must be late summer or maybe early autumn as many of the trees have shed their bronze-tinted leaves while others cling to the branches and retain their summer colour. To the side of the road is a pavement. Look at the details Marie has depicted of the sidewalk. The fallen bench straddles the pavement and the road. The crumbling stonework of the pavement is clearly visible and which is now home for the fallen, windswept leaves and what looks like an abandoned newspaper lies in the gutter close to the fallen bench. Beside the pavement we see a stretch of garden fencing which has seen better days. This is an example of Naturalism in art, a style Marie Bashkirtseff had adopted due to the influence of her close friend, Jules Bastien-Lepage. The painting is devoid of people and this fact alone means we are not distracted from the artist’s detailed depiction of the area. It also avoids the work of art being focused on people and the depiction of them may turn the painting into a work of Social Realism with the landscape being looked upon as merely a background to a story within the work. The colours used by the artist set the scene for a certain time of year and also a certain time of day. One can imagine the lighting of the scene would be different at another time of day and obviously it would be a far different depiction if this had been mid-winter.

In a diary entry for May 1884, she wrote:

“…What is the use of lying or pretending? Yes, it is clear that I have the desire, if not the hope, of staying on this earth by whatever means possible. If I don’t die young, I hope to become a great artist. If I do, I want my journal to be published…”

Four months after this entry, on October 31st 1884, Marie Bashkirtseff died of consumption (pulmonary tuberculosis) in Paris. She was just twenty-five years old and for her, she sadly believed she had achieved little.

She was buried in Cimetière de Passy in a large mausoleum, designed as a full-sized artist’s studio and has now become a French Heritage site. The inside of Marie Bashkirtseff’s mausoleum we see in the central background a copy of Marie’s bust which was sculpted by her friend the sculptor René de Saint Marceaux. Behind the sculpture hanging on the wall is one of Marie Bashkirtseff’s last and unfinished paintings entitled Women Saints. At either side, on pedestals are busts of her parents Sadly almost two hundred of her works were destroyed or looted during the Second World War. However her journal was published by her family in 1887. Sadly it was an abridged version which had been heavily censored by her relatives who thought a lot of the contents about them were unflattering seeing to it that a good deal of material was critical and unflattering to the family and unfit for the reading public. Having said that however, the diary stands as one of the great diaries of its time. It was not until some years later, with the discovery of Marie’s original manuscript in the Bibliothèque nationale de France that it was realised that the diaries published by the family had been heavily edited. An unabridged edition of the complete journal, based on the original manuscript, has been published in French in 16 volumes, and excerpts from the years 1873–76 have been translated into English under the title I Am the Most Interesting Book of All.

The diaries were started by a girl of fourteen and they began as a simple coming-of-age journal but later developed into an often sad account of how life conspired against her and her fight to survive.

I will leave you with an entry in her diary when she talks about how people may remember her. She wrote:

“…If I do not die young I hope to live as great artist; but if I die young, I intend to have my journal, which cannot fail to be interesting, published. Similarly: “When I am dead, my life, which appears to me a remarkable one, will be read. (The only thing wanting is that it should have been different)…”