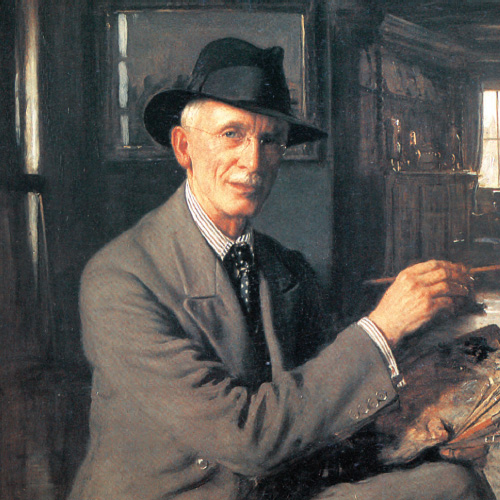

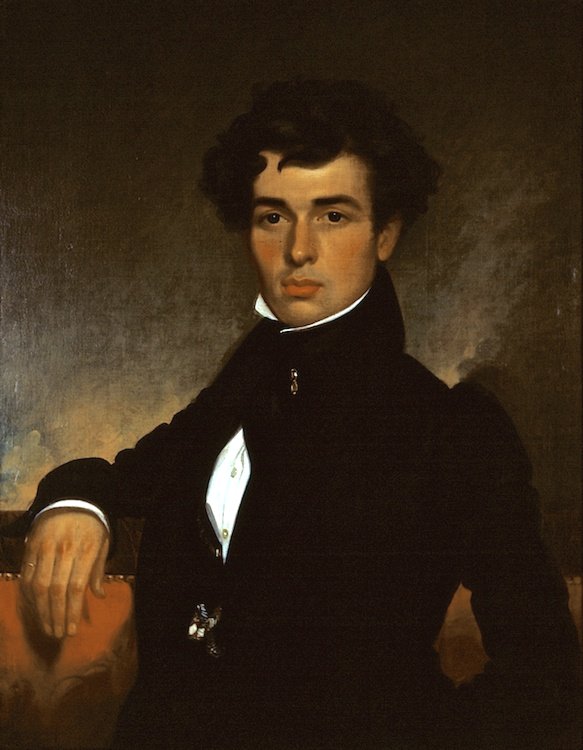

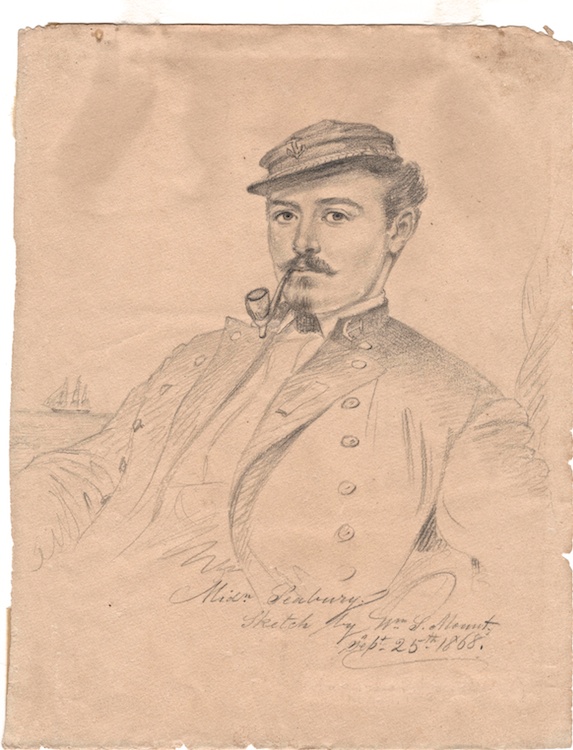

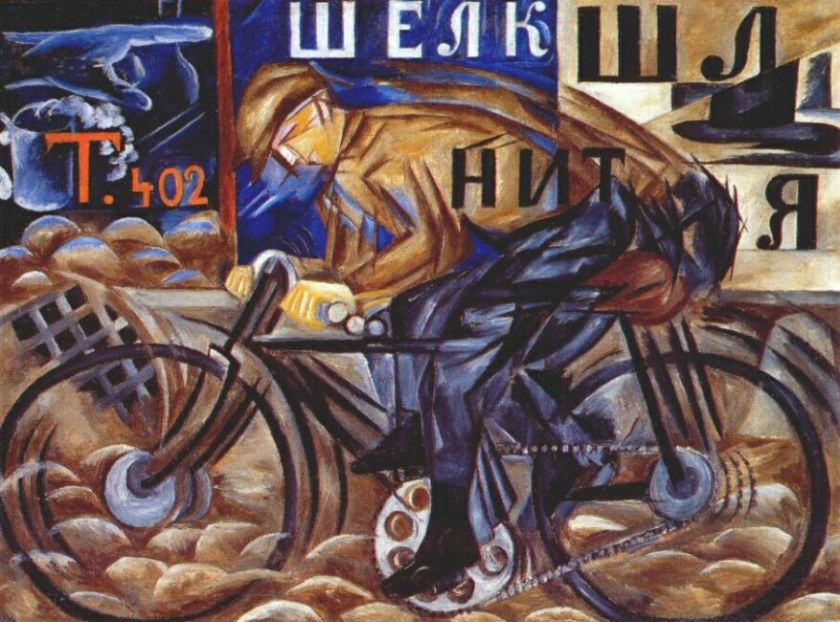

(Self Portrait)

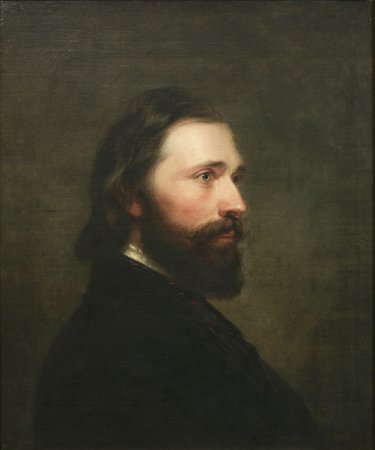

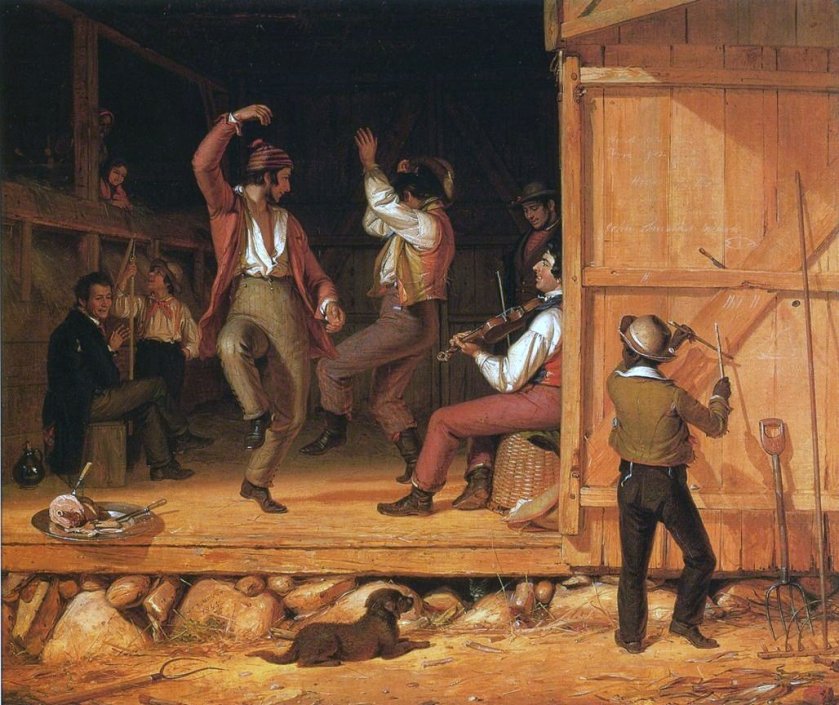

There is something very intriguing about “–isms” when talking about genres in art. We are all aware of them common ones such as realism, impressionism, cubism, etc. In fact I have an art history book about “-isms”. Today I want to introduce you to another “-ism” which is not mentioned in the knowledgeable tome. It is ruralism, often referred to as Rural Naturalism, an art genre through which artists pictorially champion life away from the grime of cities and, through their paintings, exalts life in the countryside. One of the great exponents of ruralism is the subject of my next two blogs, the English painter, Sir George Clausen.

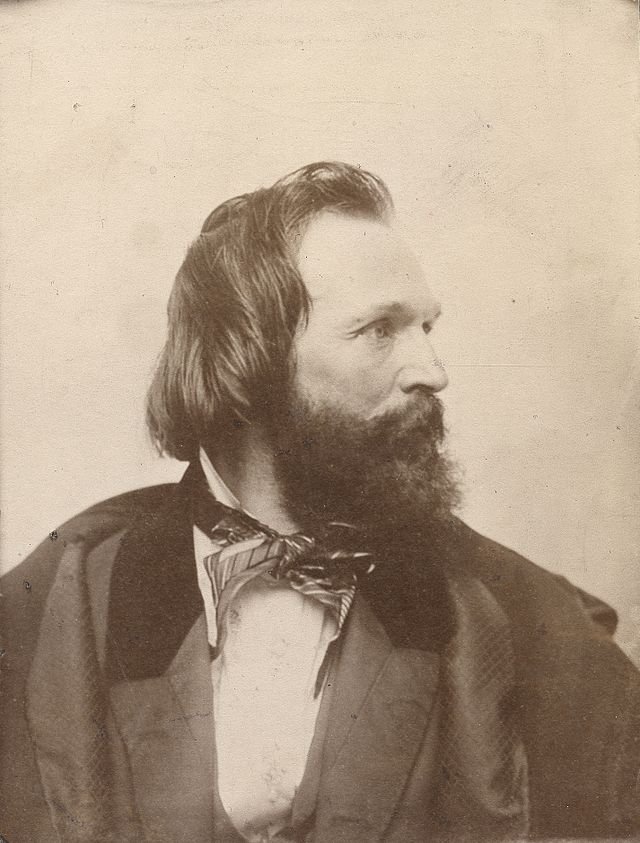

George Clausen was born 8 William Street, Regents Park, London in April 1852, the son of Jorgen Johnsen and Elizabeth Clausen. His father, an artist and interior decorator, was of Danish extraction and his mother was of Scottish descent. Up until the age of fourteen and a half, George attended St Mark’s School in Kings Road Chelsea. In 1867, three months before his fifteenth birthday he started a five year apprenticeship in the Chelsea drawing office of Messrs. Trollope, a firm of interior decorators. During this period he was trained in drawing by John Cleghorn, whose job title was a copyist and limner, an old term for a painter of ornamental decoration, a book illustrator or somebody who illuminates manuscripts. Cleghorn had an artistic background having studied at The Royal Academy Schools. George Clausen had a thirst for artistic knowledge and to supplement Cleghorn’s tuition, also attended evening classes at the National Art Training School, South Kensington, which in 1896, would become the Royal College of Art. One of the jobs Clausen was involved in was to decorate the home of the English genre, history, biblical and portrait painter, Edwin Long. Clausen’s boss, an Irish man called Brophy, gave Clausen the task to paint some lilies on the panels of a door in Edwin Long’s house. Clausen remembered this time and it must have made an impression on him, for sixty years later in his Autobiographical Notes which appeared in the Spring 1931 edition of the Artwork magazine he recalled the time:

“…Long looked at my work and said ‘May I see your sketchbook?’ He gave it back to me and said ‘Did you ever think of becoming an artist?’ I said ‘Yes, but I saw no opportunity of getting the training.’ Long said ‘I think you’d have a chance. And if I were you I’d try for a scholarship at South Kensington.’ Brophy readily agreed. I had already taken medals in design, and I was worked up in my spare time, and obtained a two years’ scholarship in decorative painting at £50 a year!…”

Clausen was not enamoured by the training he received during the two year course at South Kensington School of Art. He believed that there was not enough teaching and lacked structure as students were left to get on with things themselves.

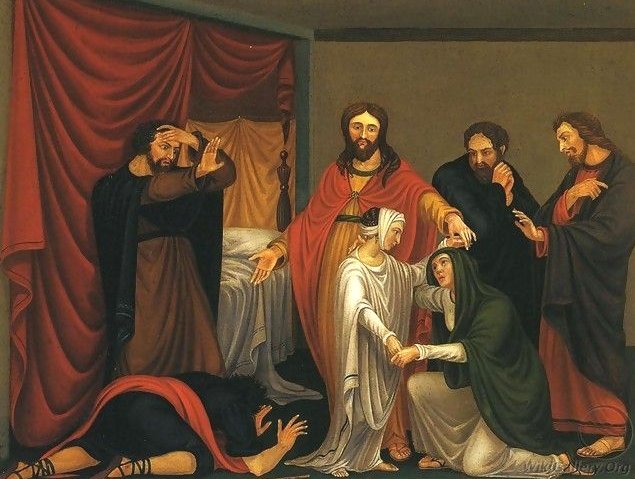

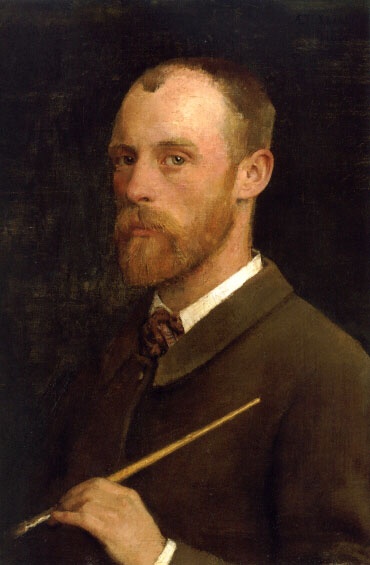

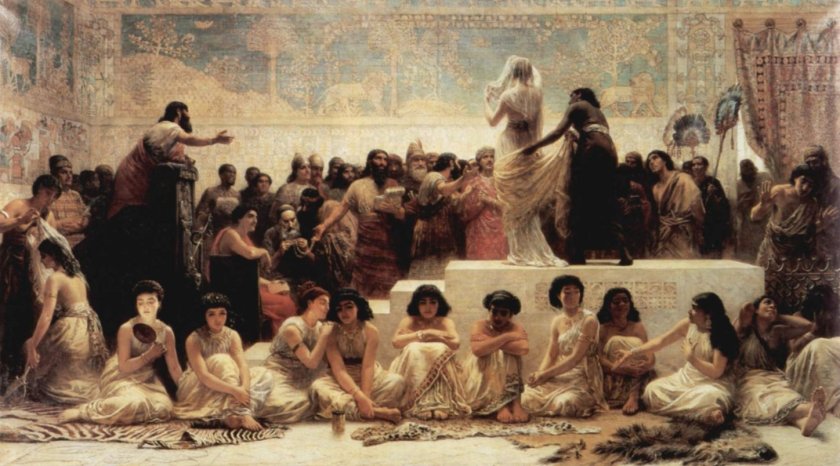

He did however keep in contact with Edwin Long and did a lot of research work for him with regards some of Long’s large biblical paintings. Long would pay Clausen for his help and also tutored him. Long realised that Clausen’s artistic ability needed to be carefully nurtured and believed, for Clausen to receive the best artistic tuition, he needed to leave England and move to Antwerp and attend the Antwerp Academy of Art.

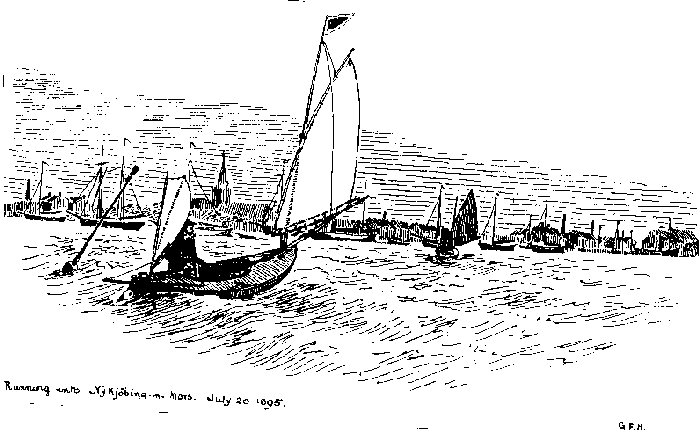

George Clausen accepted the advice and travelled to Holland and Belgium and for a short period enrolled at the Antwerp Academy where he studied under the tutelage of Professor Joseph van Lerius. His sketches and paintings around this time were heavily influenced by Dutch subjects such as the coastal fishing villages and he exhibited a number of these at the Dudley Gallery, which was originally located in the Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly, London. It was completed in 1812 and financed by Earl of Dudley to house his valuable collection of pictures during the erection of his own gallery at Dudley House in Park Lane. It was known for its promotion of French and Dutch artists.

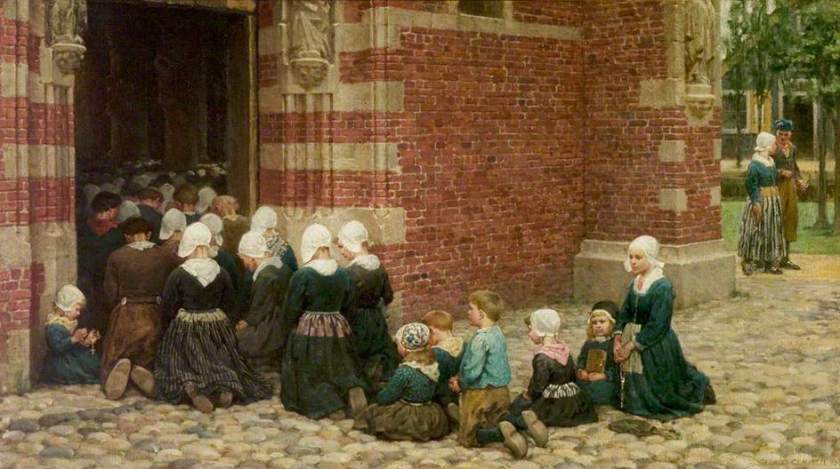

One example of Clausen’s “Dutch period” was his small (47 x 84 cms) oil on canvas painting entitled High Mass at a Fishing Village on the Zuider Zee, which he completed in 1876 and is part of the Nottingham Castle Museum collection. The work was the result of a summer holiday Clausen had taken to the island of Marken, in the Zuider Zee, with his friend and fellow artist Dewey Bates. They had visited the village of Volendam on a Sunday, where there was a celebration of a High Mass. The mass was so well attended that the church was full and many parishioners were left outside. In the painting we see into the fully occupied church as well as a group of fishermen with their wives and children kneeling on the cobbled street outside the main entrance door.

The painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy, the first work he had ever submitted to the prestigious establishment, and the art critic of The Times, seeing the work of art and Clausen’s name immediately believed he was a Dutch artist painting a scene from his homeland and wrote :

“…a very clever Dutch painter, hitherto only known in this country by two drawings exhibited at the Dudley Gallery…”

The art critic of the Spectator was full of praise writing:

“…a quiet thoughtful picture, in every sense of the word. A work of true art and deep feeling…”

Whilst in Europe George Clausen made many visits to Paris. His paintings around this time showed that he had been influenced by the likes of Whistler and William Quiller Orchardson, a well loved Scottish portraitist and painter of domestic and historical subjects. He was also very interested in the rustic natural depictions of the Scottish artist John Robertson Reid and Léon Augustine Lhermitte, a French realist painter, whose primary subject matter was of rural scenes depicting the peasant worker.

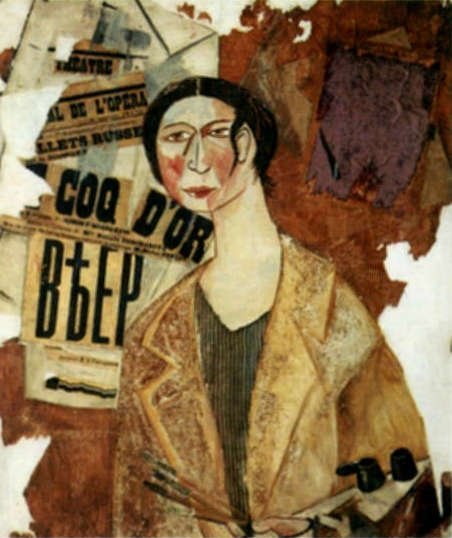

In 1880 Clausen exhibited his work La Pensée at the Grosvenor Gallery in London. It was a difficult depiction for an artist with the model seated in an interior. The figure is not seated parallel to the plane of the picture and the rear wall. It is a work of art full of detail. Look at the right background and you can see the edge of an elaborate chimney piece. In the left background there is a drop leaf table and on the floor a goat skin rug. The lady sits upright in the chair looking out at us whilst grasping a knot of violets in her right hand which rests in her lap. This is the key to the title of the painting (Thought). Here is a lady lost in thought about her lost love.

Clausen often used this model for his paintings and one I particularly like featuring her was completed in 1881 and entitled a Spring Morning, Haverstock Hill. It was exhibited at that year’s Royal Academy exhibition. This London street scene was an ambitious work featuring not just the main female model, who walks along the street accompanied by a small child, but a number of other characters some at rest, some at work, including labourers digging up the cobbles in the road and, directly behind the main character, a flower seller.

When Clausen exhibited La Pensée at the Grosvenor Gallery amongst his fellow exhibitors was Jules Bastien-Lepage who was exhibiting nine paintings, including Les Foins (Haymaking), which depicts resting haymakers. This painting had been exhibited at the Salon in 1878. Clausen, like the critics, were enthralled by this work of rural or rustic naturalism. Clausen shortly after moved to the countryside and went to live in the Hertfordshire village of Childwick Green. He later wrote in his 1931 Autobiographical Notes about his new surroundings and the new opportunity and challenges it gave him as a painter

“…One saw people doing simple things under good conditions of lighting: and there was always a landscape. And nothing was made easy for you: you had to dig out what you wanted…”

Soon his sketchbooks were full of sketches and paintings depicting workers in the countryside surrounding his house. One of Clausen’s first works depicting labourers in the fields was completed in 1882 and was entitled The Gleaners. The work was exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1882. It was greeted with great acclaim by the critics and art reviewers. In Vol. V 1881-2 of The Magazine of Art, the reviewer wrote about how Clausen sympathetically depicted the labourers:

“…He shows us a little company of the poor not in picturesque rags but in garments of fact, gleaning modern English fields…”

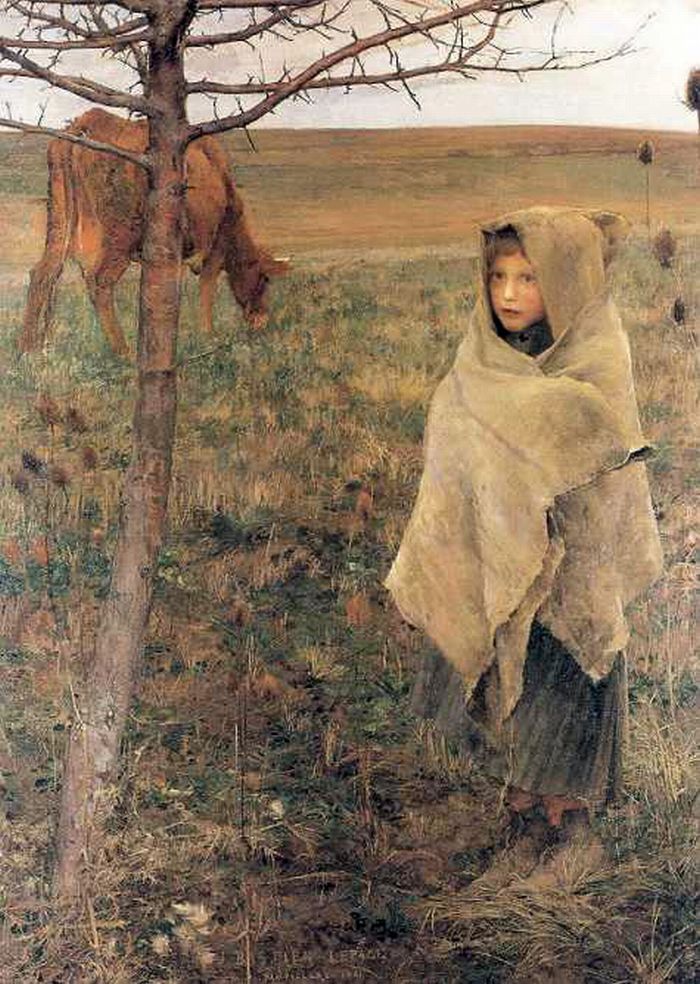

In 1881 Bastien-Lepage completed a work entitled Pauvre Fauvette. He often painted the peasants from the town he was living in at the time, Damvillers which is situated in north-eastern France. In his painting we see a very small young girl, the ‘little wild girl’ of the painting’s title. Her job is to patiently and quietly guard a cow, which we see on the other side of the tree. In a way it is a depiction of isolation in the way the artist has depicted the small child, even dwarfed by the tall thistles. She stands alone next to a leaf-less tree surrounded by a very barren landscape. It is a pitiful depiction and we note her haunted and sad eyes and the way she tries to cover herself up and keep herself warm in a threadbare blanket leads us to believe it could have been a cold winter’s day.

The next work I am featuring was also probably influenced by Bastien-Lepage’s work above. It was one which Clausen began in the autumn of 1886 and completed in 1887. It was entitled The Stone Pickers. On completion Clausen sent it to Goupil, the art dealer and in 1887 it was exhibited at the Dudley Gallery, London and also appeared at the second New English Art Club exhibition of 1887. It is now housed at the Laing Gallery in Newcastle upon Tyne. The model for the painting was Polly Baldwin and the setting was at Cookham Dene. Look how in this work the girl has sacking wrapped around her lower body to keep her warm, similar to the attire of the child in Bastien-Lepage’s painting. Stone pickers were sent out into the fields to pick up loose stones prior to ploughing. In Clausen’s painting we see a young girl depositing stones, which she had picked up, on to a pile. In the background we see another woman bent down picking up stones from the field. One can only imagine what a backbreaking and tedious job the women had to endure. Many artists of the time liked to depict hard working labourers/peasants at work in the fields, This was the essence of rustic realism or rustic naturalism. Look at the expression on the young girl’s face as she looks down at the pile of stones. It is a sad and almost haunted expression. Behind her there is a can containing water and a wicker basket containing food for her lunch. Our eyes are drawn to this area because of the red colour of what could be a table cloth.

In my next blog I will complete Clausen’s life story and have a look at some more of his works of art.