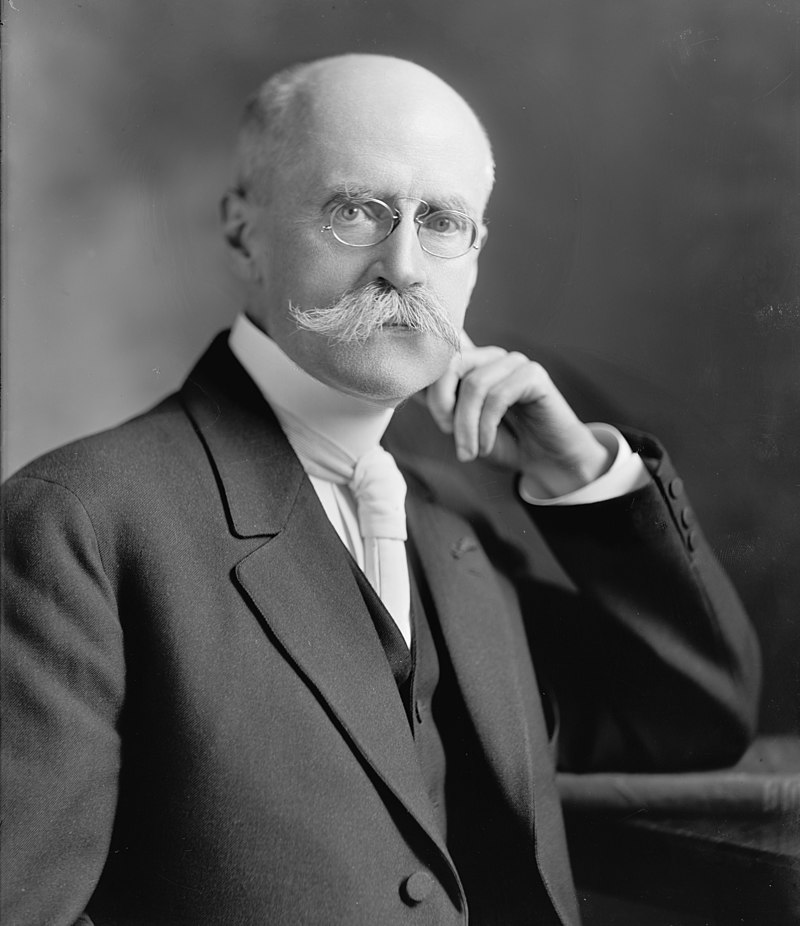

The artist I am looking at today is the late nineteenth century American painter, muralist, art historian and travel writer, Edwin Howland Blashfield. Blashfield was born on December 5th 1848 in Brooklyn. He was the son of William H. Blashfield and Eliza Dodd. His father was an engineer and wanted his son to follow in his footsteps. On the other hand, his mother, Eliza, had been trained as a portrait painter and she encouraged her son’s artistic studies. His father’s wishes for his son’s future were granted, and in 1863, aged fifteen, Blashfield travelled to Hanover, Germany, to study engineering. The death three months later of his companion and godfather, Edwin Howland, necessitated in his return to the United States. Once on home soil, he enrolled on and engineering course at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts, which lasted for two years.

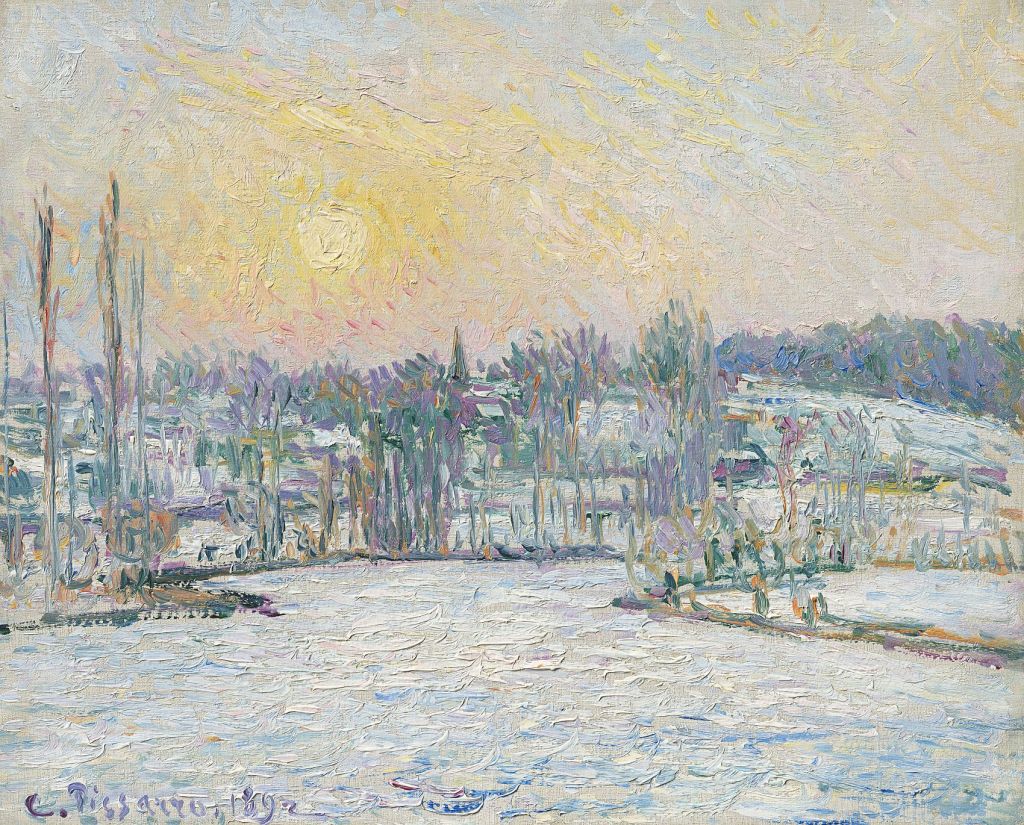

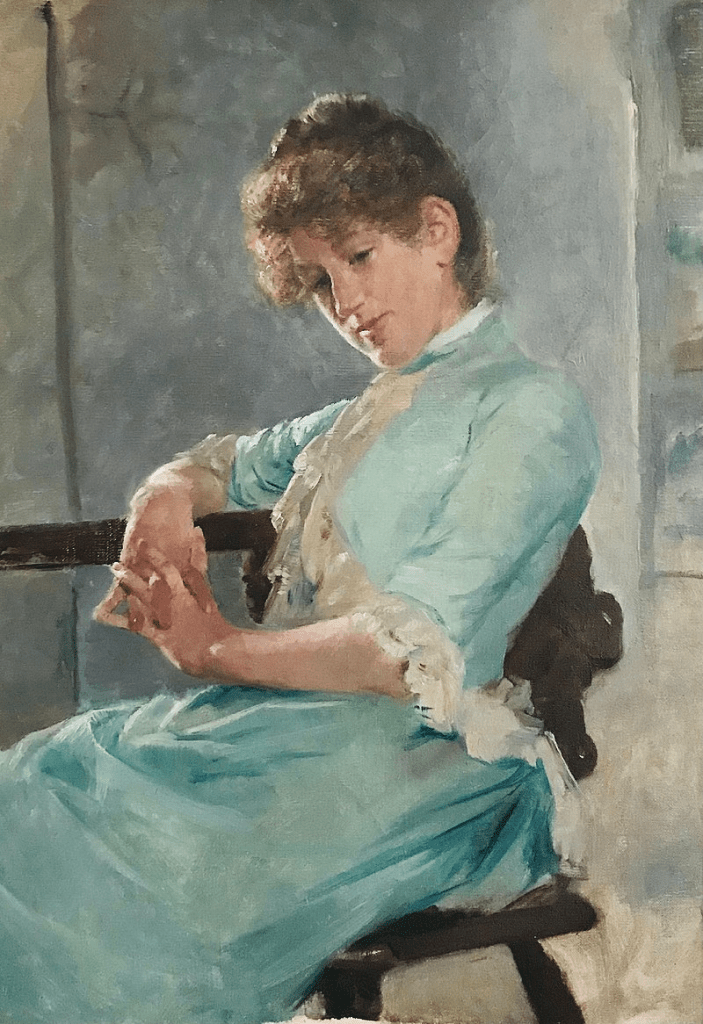

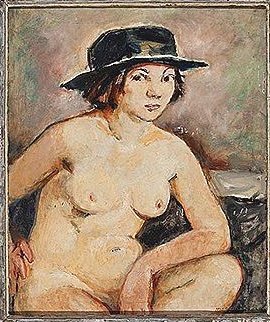

The Roman Pose by Edwin Blashfield

While studying at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, his mother, sent some of his drawings to the French academic painter Jean Léon Gérôme, whose praise for Edwin’s work persuaded his father to allow him to take up a career in art. Blashfield followed his technical training with three months of study with Thomas Johnson, who had once been a pupil of William Morris Hunt, the American Romantic painter. He then travelled to Paris in 1867 to gain more artistic training but was denied entrance to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, so, instead, he took a place in the studio of the French history and portrait painter, Léon Bonnat from 1867 to 1870. As well as the tuition, Blashfield met great artists living in the French capital such as Pierre Puvis de Chavannes and William-Adolphe Bouguereau whose work greatly influenced him. Blashfield led a good life in Paris thanks to his inherited wealth and during the summers he would head for the French countryside. In late 1870 the Franco-Prussian War began and Paris was under siege and later came the uprisings in the French capital, so ending his artistic training, and so to escape the troubles he travelled around Europe, visiting Belgium and then went to Florence where he remained for eight months. He returned home to New York in 1871 and for the next three years he painted mainly costume pictures of fashionable ladies.

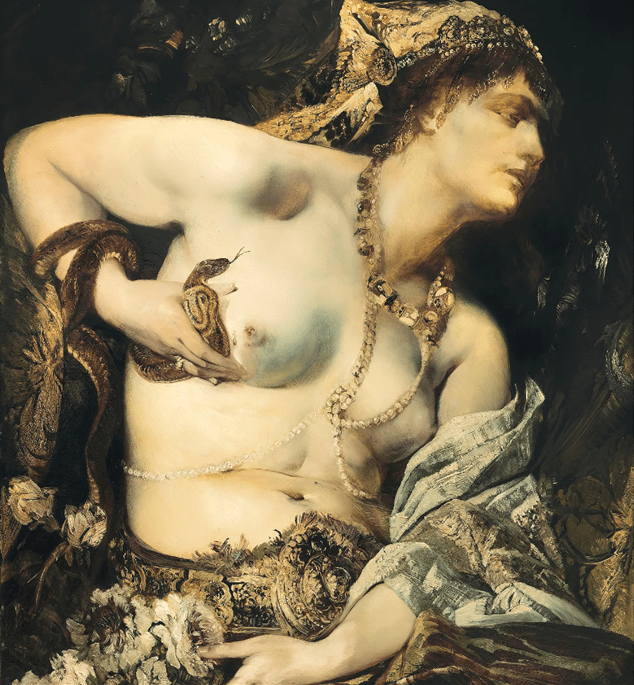

The Lover’s Advance by Edwin Blashfield

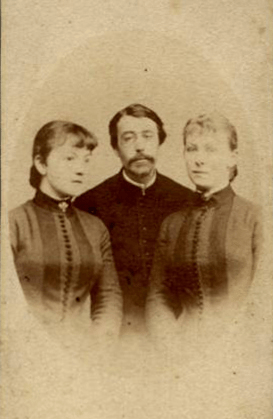

He returned to Paris in 1874 and re-enrolled at Léon Bonnat’s studio where he became great friends with fellow American painters Elihu Vedder, H. Siddons Mowbray, and Frederick A. Bridgman. In 1876, he met writer Evangeline Wilbour, a pioneer of women’s history, and activist. Evangeline was born in 1858 and often summered in her birthplace, Little Compton, Rhode Island, though she lived much of her life in New York. She was the eldest of four children of Charles Edwin Wilbour and his wife Charlotte. Her father’s principal business was ownership of a large paper manufacturing company and had connections with Tammany Hall, a New York City political organization, which became the main local political machine of the Democratic Party and played a major role in controlling New York City and New York State politics. It was through this connection that Charles Wilbour received many contracts and made his fortune from William “Boss” Tweed the political boss of Tammany Hall. Tweed fell from grace in 1871 and eventually in 1873 he was jailed for corruption. To escape any fall-out from this, Evangeline Wilbour’s father decided to hastily leave the United States in 1874, and move to Paris with his family.

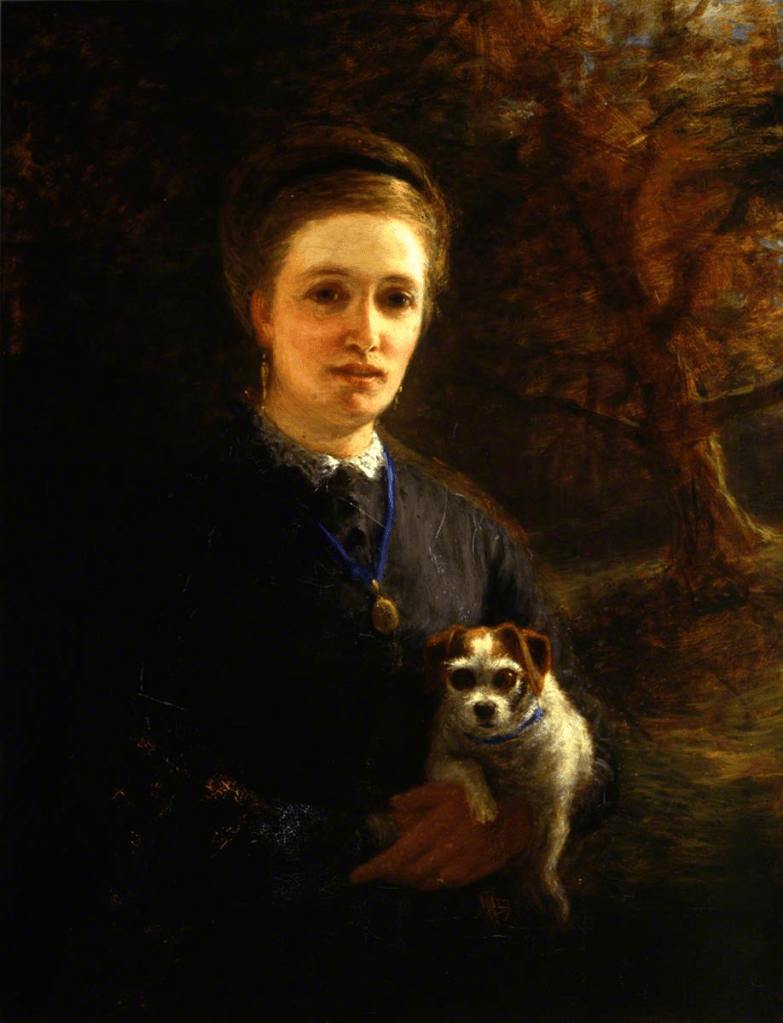

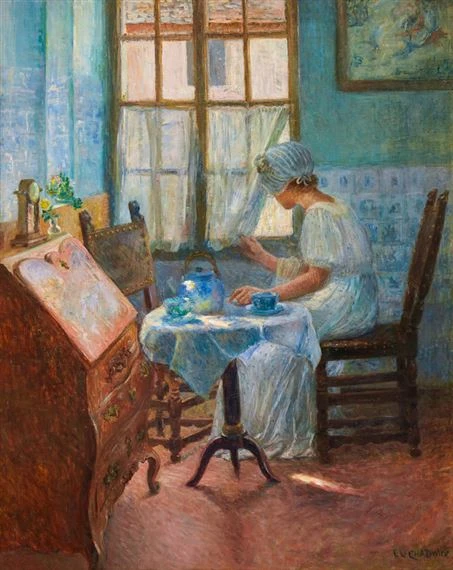

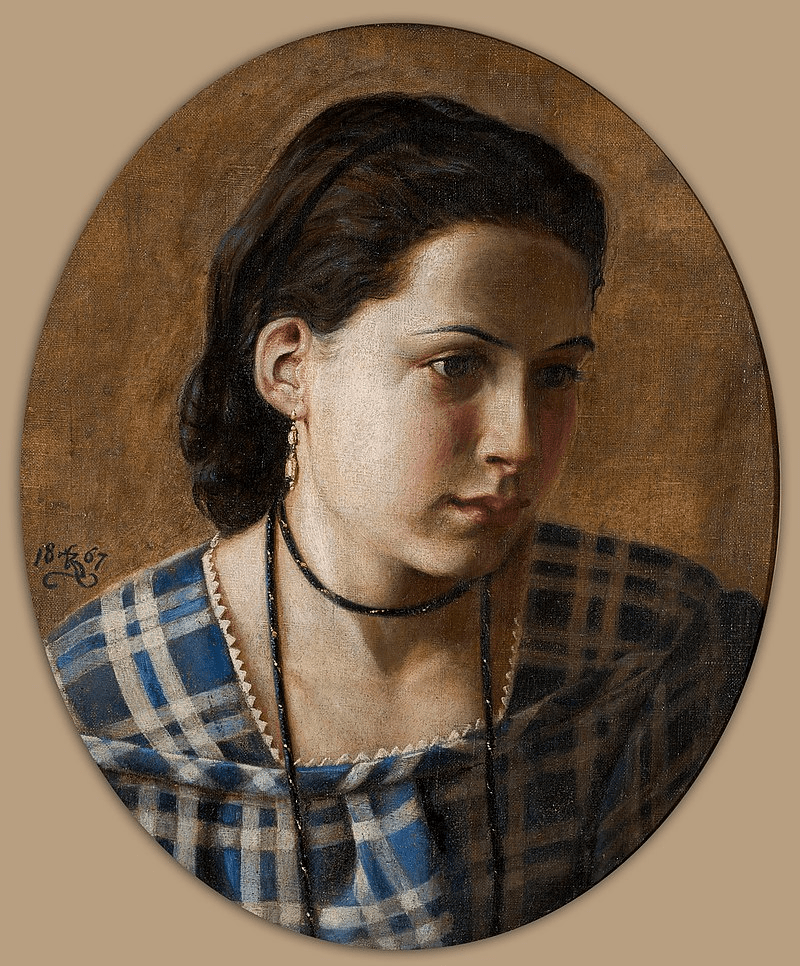

Evangeline Blashfield née Wilbour

Evangeline spent a short time in finishing schools in Florence and Paris but despite her interrupted education, her insatiable curiosity and her never-ending search for knowledge, she was looked upon as one of the most learned people of her era: fluent in French and Italian, capable in German, Arabic, and Latin; a world-class expert on history, art history, literature, and theatre.

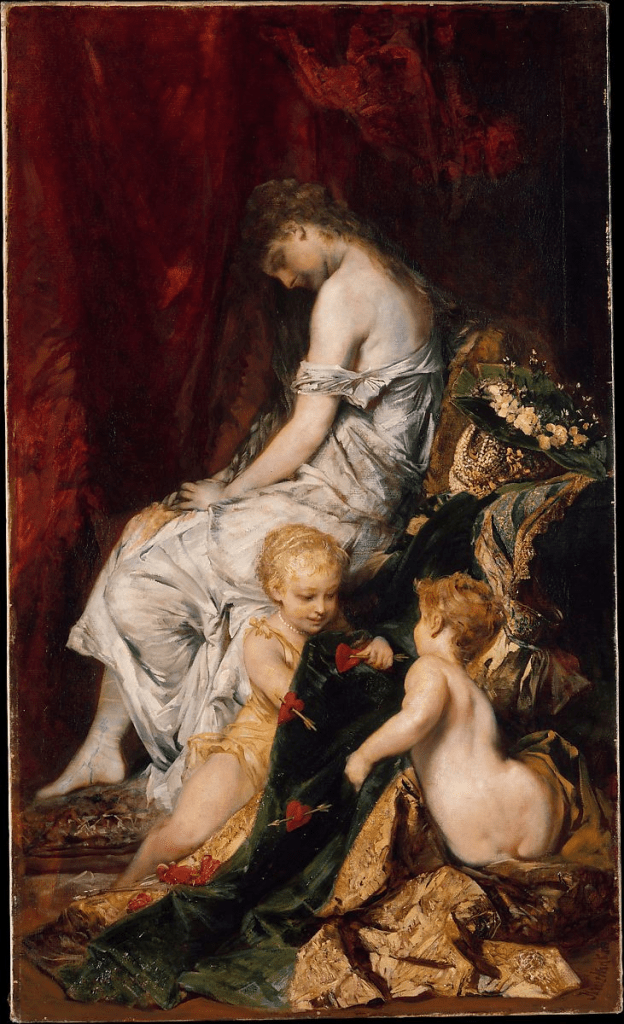

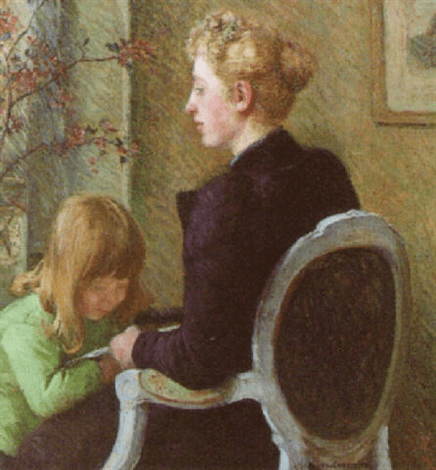

The Dolls by Edwin Blashfield

Evangeline and Edwin Blashfield met at a dance in Paris in 1876. Blashfield introduced her to his art, which consisted mainly of painted pictures of ladies in fancy dress, which he sold. Evangeline and he developed a close friendship but she believed he could better himself as his main source of income was squandered on parties and trips to London. Evangeline knew that Edwin must change his modus operandi if he was to succeed. Having met Evangeline, Blashfield’s painting motifs changed and he started to depict female gladiators fighting each other with swords, ancient women artists, and theatrical female figures thrilling with passionate intensity but this was just the start of the change Evangeline envisaged for Edwin. The couple married in 1881 and she provided him with a substantial income. Edwin gave up his studies with Bonnat and the couple returned to New York They set up home in the newly built studios in the Sherwood Building on West 57th Street, which was home to many of the emerging young artists of the generation.

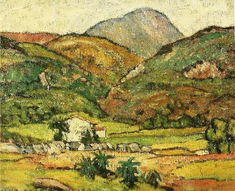

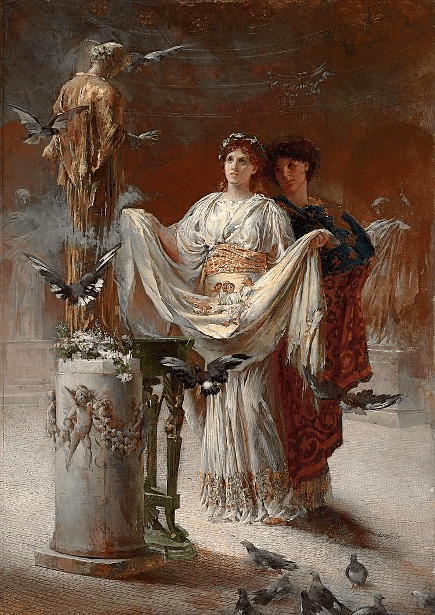

The Roman Aviary by Edwin Blashfield

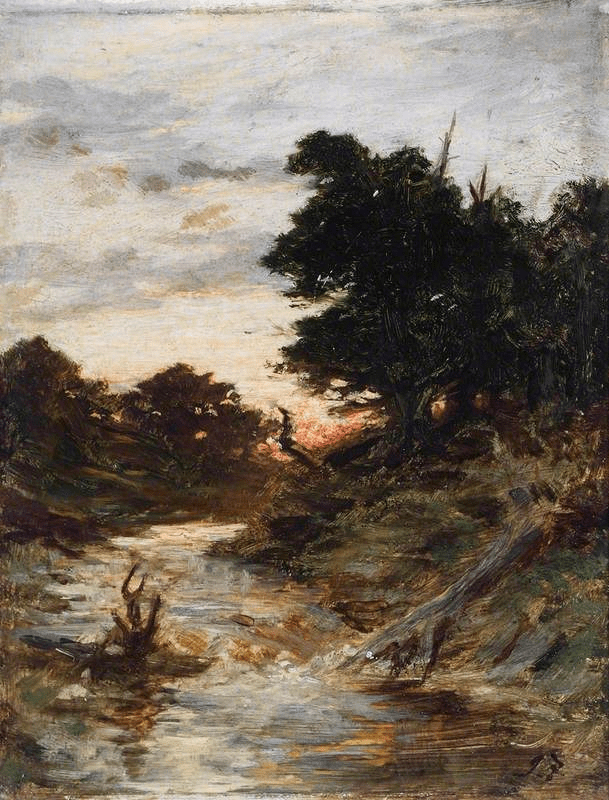

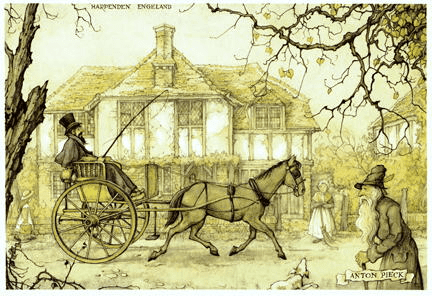

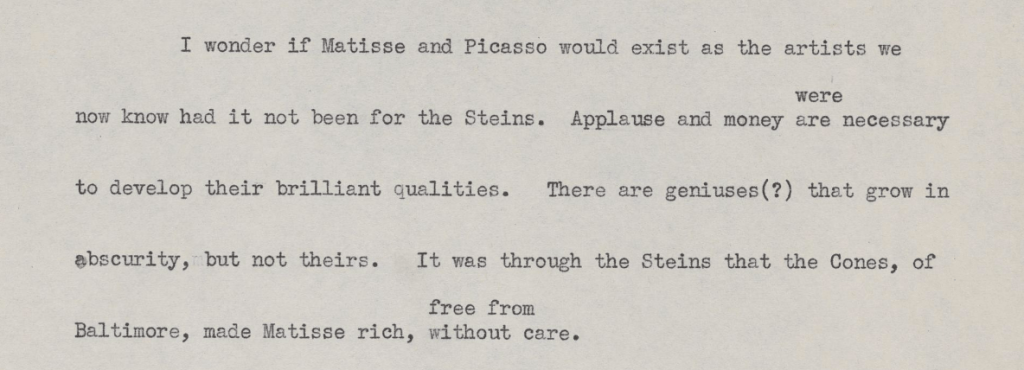

Evangeline persuaded her husband, who was now financially sound, to abandon his painting and selling small easel pictures and instead concentrate on painting larger and more ambitious works. However, Blashfield continued painting whimsical genre pictures and also did illustrations for the St. Nicholas Magazine. Soon after returning to New York, he worked together with his wife, producing illustrated articles for Century Magazine and Scribner’s Magazine. Edwin and Evangeline Blashfield returned to Europe in 1887, spending time at the artist colony of Broadway, in the heart of the English Cotswolds, where they met fellow painters, Francis Millet, the leading light of the group, from Mattapoissett, Massachusett, Edwin Austin Abbey, the American muralist and John Singer Sargent. These artists, who were mainly American, were attracted to the village by its idyllic rural nature.

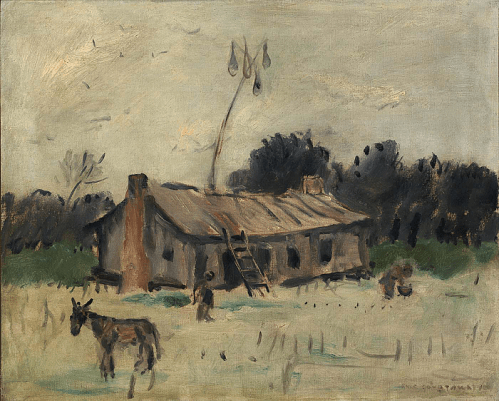

Iliad, The Luxor Barber by Edwin Blashfield

Later that year the Blashfields continued their travels and took a boat trip to Egypt and went to sail on the Nile aboard the boat owned by Evangeline’s father. Her father Charles Wilbour had escaped America and the time of the fall of William “Boss” Tweed and the Tammany Hall corruption scandal which might have touched him, due to the many contracts his paper-making business had with Tweed. Charles Wilbour then had concentrated on his love of all things to do with Egypt and he visited Europe and spent his time studying the Egyptian treasures of the British Museum and other great European collections. He became associated with many well-known Egyptologists and went on five Nile River expeditions. He bought a boat which was moored on the Nile.

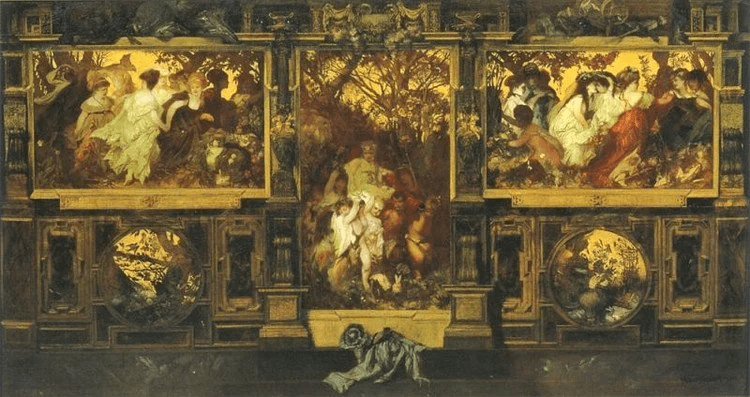

The Columbian Exposition (Chicago’s World Fair ) (1893)

Influenced by his wife, Blashfield agreed to concentrate are large scale paintings and murals, and soon in the 1880s he became America’s foremost authority on mural and monumental painting after his success at the Chicago World’s Fair. The Chicago World Fair was held in Chicago in 1893. It was also known as the World’s Columbian Exposition as a celebration of the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the New World in 1492. The Fair was held in Jackson Park, with the centrepiece being a large expanse of water epitomising the voyage Columbus took to explore the New World. The exposition was an influential social and cultural event and had an insightful effect on American architecture, the arts, American industrial optimism, and most of all, Chicago’s image. In 1892 Blashfield was approached by the American academic classical painter, sculptor, and writer, Francis Davis Millet, whom he had previously met whilst visiting the Broadway artist colony in Worcestershire. Millet, a member of the Society of American Artists in 1880, and in 1885, was elected as a member of the National Academy of Design, New York and as Vice-Chairman of the Fine Arts Committee. He was made a trustee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and sat on the advisory committee of the National Gallery of Art. He was decorations director for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. He wanted Blashfield to contribute a mural, The Art of Metalworking, for one of the domes of the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building of the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago. The murals Blashfield completed for Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building of the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago were loved by attendees and it led to many more mural commissions.

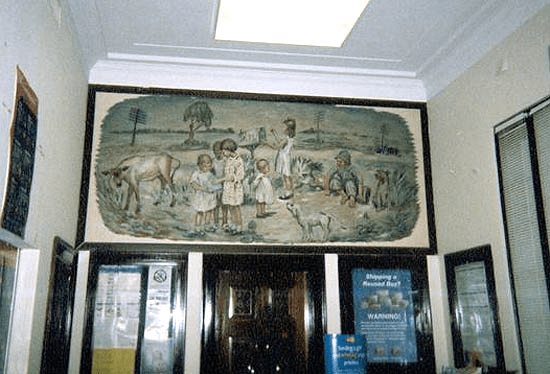

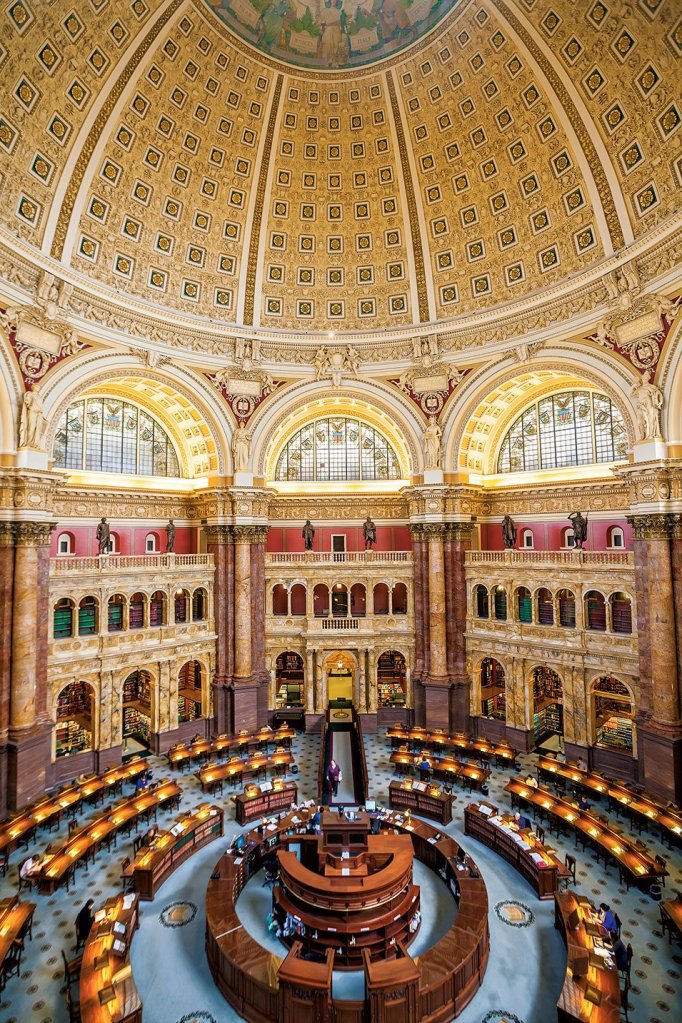

Edwin Blashfield’s mural for the interior of the dome of the Library of Congress Thomas Jefferson Building.

One such commission was for the interior of the dome of the Library of Congress Thomas Jefferson Building. It was decided that Blashfield’s murals would adorn the dome of the Main Reading Room, occupy the central and the highest point of the building and form the culmination of the entire interior decorative scheme.

His murals would decorate inside the lantern of the dome and depict Human Understanding. They would be observed above the finite intellectual achievements which were represented by the twelve figures positioned in the collar of the dome. These twelve seated figures represented the twelve countries, or periods, which Blashfield felt added the most to American civilization. On the right of each figure was a tablet on which was inscribed the name of the country typified and, below this, the name of the exceptional contribution of that country to human development.

Egypt represents Written Records.

Judea represents Religion.

Greece represents Philosophy.

Rome represents Administration.

Islam represents Physics.

The Middle Ages represent Modern Languages.

Italy represents the Fine Arts.

Germany represents the Art of Printing.

Spain represents Discovery.

England represents Literature.

France represents Emancipation.

America represents Science.

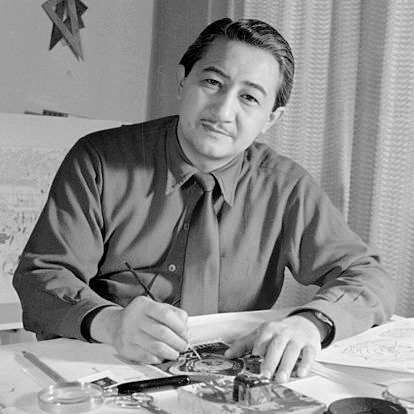

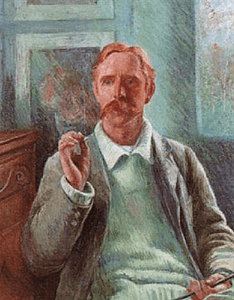

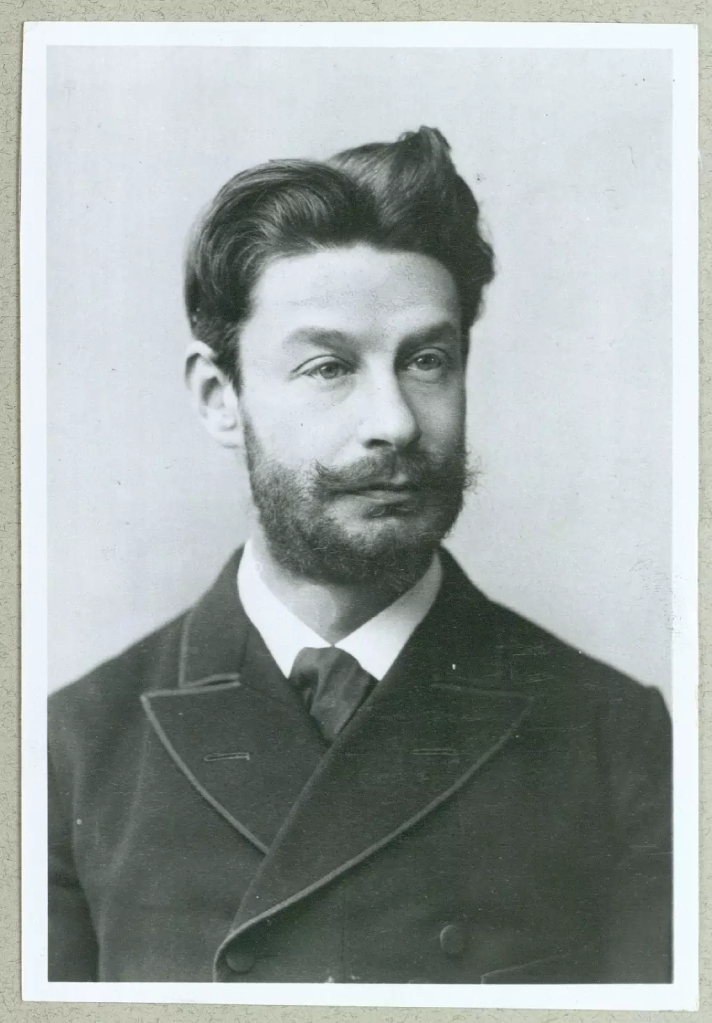

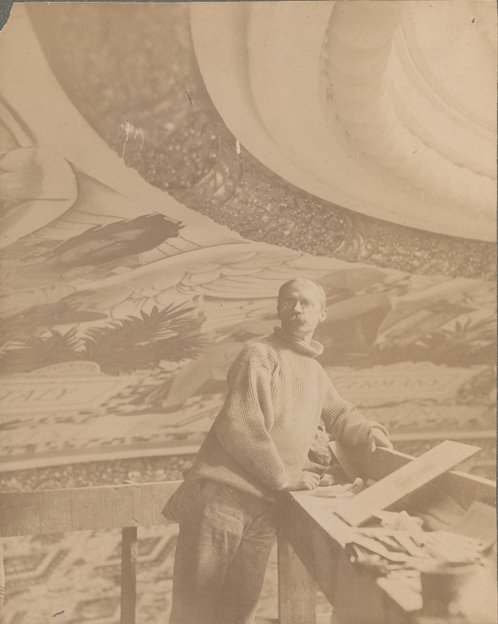

Edwin Blashfield at work on his murals

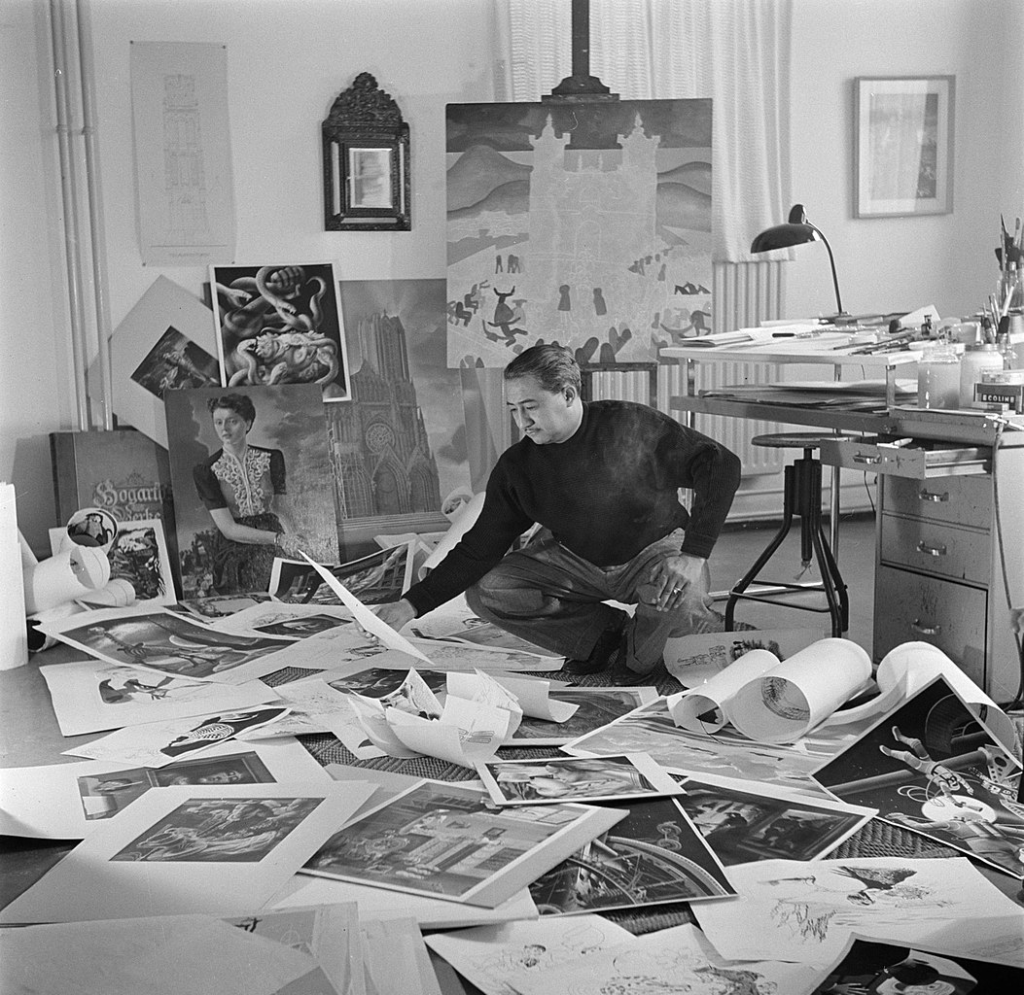

The precarious staging need by Blashfield to paint the murals

Blashfield’s murals featured in courthouses, state capitols, churches, universities, museums, and other places across the United States, including the grand ballroom of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, New York

Westward – mural by Edwin Blashford

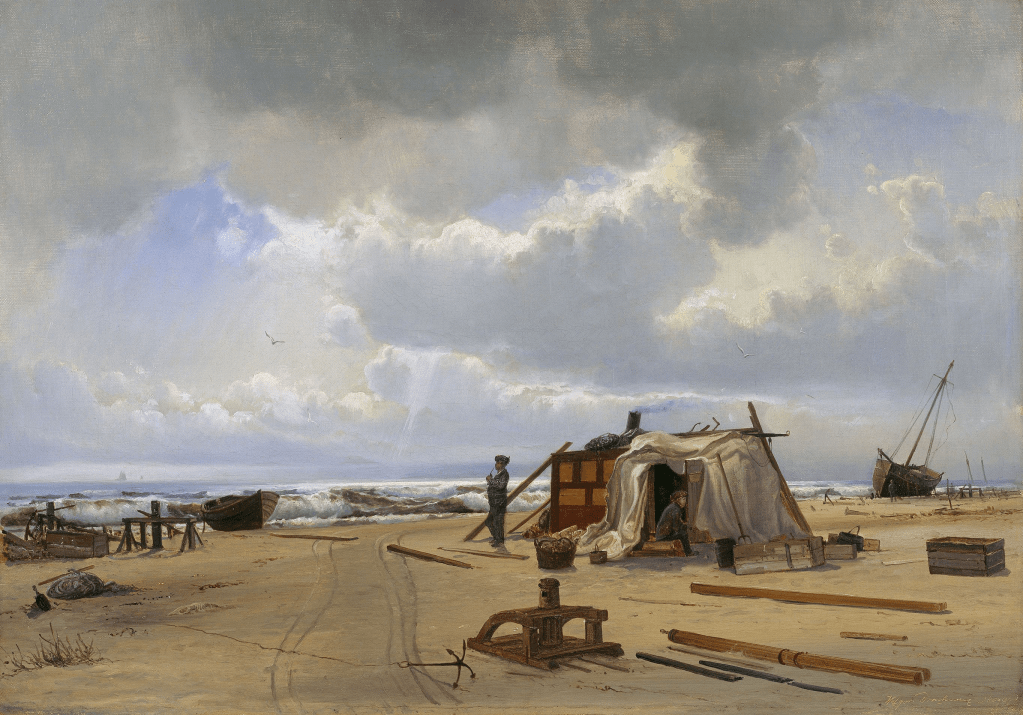

Blashfield completed a mural for the Iowa State Capital Building in Des Moines, which extended the full width of the east wall above the staircase. The mural painted by Blashfield in 1905 measures 14 feet high and 40 feet wide and is simply entitled Westward.

Detail from the Westward mural

It was painted on six pieces of canvass and placed into the frame. It is an idealised representation which depicts early pioneers, who are crossing Iowa and heading West seeking a new life.

Detail from the Westward mural by Edwin Blashfield

Blashfield described his mural, writing:

“…The main idea of the picture is symbolical presentation of the Pioneers led by the spirits of Civilization and Enlightenment to the conquest by cultivation of the Great West. Considered pictorially, the canvass shows a ‘Prairie Schooner’ drawn by oxen across the prairie. The family ride upon the wagon or walk at its side. Behind them and seen through the growth of stalks at the right, come crowding the other pioneers and ‘later men.’ In the air and before the wagon, are floating four female figures; one holds the shield with the arms of the state of Iowa upon it; one holds a book symbolizing Enlightenment; two others carry a basket and scatter the seeds which are symbolical of the change from wilderness to ploughed fields and gardens that shall come over the prairie. Behind the wagon, and also floating in the air, two female figures hold, respectively, a model of a stationary steam engine and of an electric dynamo to suggest the forces which come with the ‘later men.’ …”

Mural above central staircase

The mural was a reminder of the courageous journey taken by pioneers travelling west to set up home and achieve a new life for their families and descendants. A truly noteworthy and heroic journey – or was it ? Some did not think so and wanted the mural removed. In Iowa, the Indigenous women-led activist group Seeding Sovereignty delivered a letter to officials seeking the removal of monuments and Blashfield’s mural from its State Capitol in Des Moines. Ronnie Free, a member of Great Plains Action Society, told the local newspaper, the Des Moines Register:

“…I feel it is a century long’s attempt at trying to erase the history of Indigenous peoples. It covers up genocide. The term whitewashing comes to mind. I think they’re horrible, and I hate that my children have to see that…”

In its place, activists are calling for the mural and monuments to be replaced with works that celebrate the state’s Indigenous history.

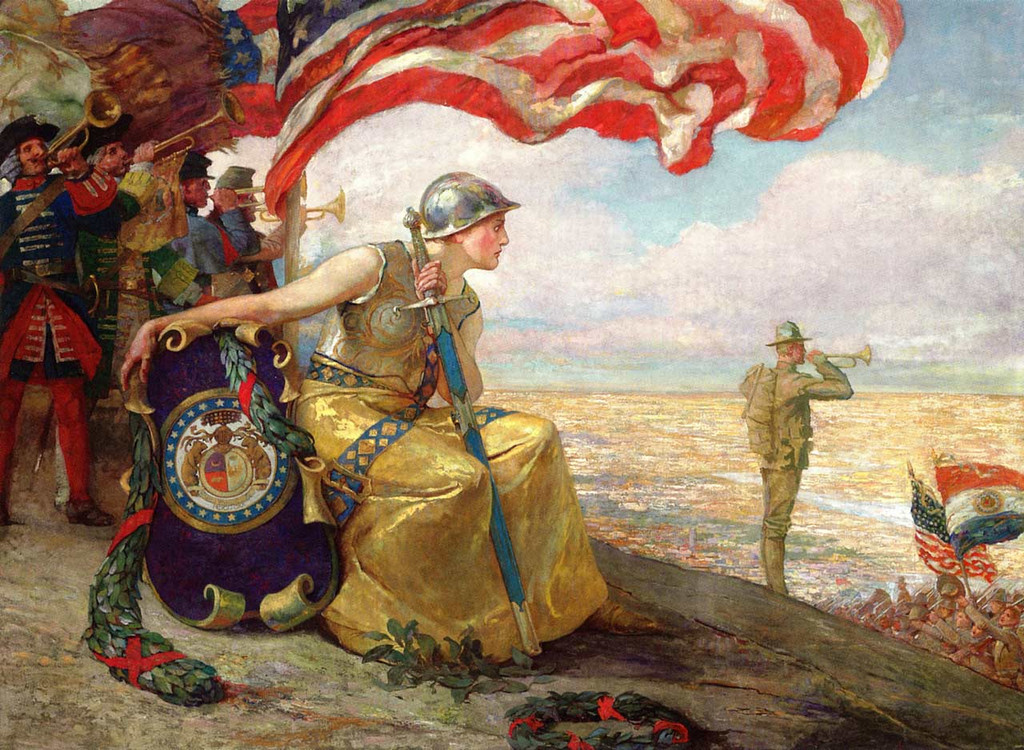

Trumpets of Missouri mural by Edwin Blashfield (1918)

In 1918, Edwin Blashfield was commissioned by the Kansas City Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution to complete a mural entitled Trumpets of Missouri which would commemorate and honour the citizens of Missouri who answered the nation’s call to arms in the First World War. The work is a rare surviving mural by the Blashfield. The Kansas City Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution was established in Kansas in 1896 and has helped promote history throughout the state from its 19th century beginning through the present. The foreground features a woman symbolizing Missouri, seated and clad in armor while watching her sons depart for war. Further historical symbolism emerges with a group of trumpeters in the background, “representing Old France, Old Spain, and the Union and Confederate forces, while in the front of her is a figure in khaki representing the Union of the present time, sounding the call to arms. Blashfield’s mural was described in the New York Times article of June 16th, 1918:

“…The composition is intended to give a historical outline of the development of the State. Before the Louisiana Purchase, Missouri belonged to France, then to Spain, and, again, to France. During the Civil War she was tossed from the Confederate to the Union side. The wide range of her racial and political affiliations is indicated in the painting. Missouri is symbolized by a seated female figure watching the departure of her troops. Over her head the Stars and Stripes billows on a strong wind in noble folds. Clad in armour, her hand grasping a sheathed sword, she looks out over a vast expanse of rolling country under a sky filled with clouds. Behind her stand a group of trumpeters representing Old France, Old Spain, the Union and Confederate forces, while in front of her is a figure in khaki representing the Union of the present time, sounding the call to arms. The troops responding are carrying the American flag and the Missouri State flag…”

Following its completion in 1918, the artwork was briefly displayed at an art gallery in Blashfield’s home state of New York, but later that year was presented by the Daughters of the American Revolution as a gift to the Kansas City Public Library to be hung in its facility at Ninth and Locust Streets. However mystery surrounds the mural and its present whereabouts. The library building was bought by U.S. Trade School and at that time the mural was in the building but sometime in the 1980s it disappeared. According to the Christies’, New York auction service website, the painting entitled Trumpets of Missouri, was sold at auction in 2014 to a private bidder for a substantial $149,000.

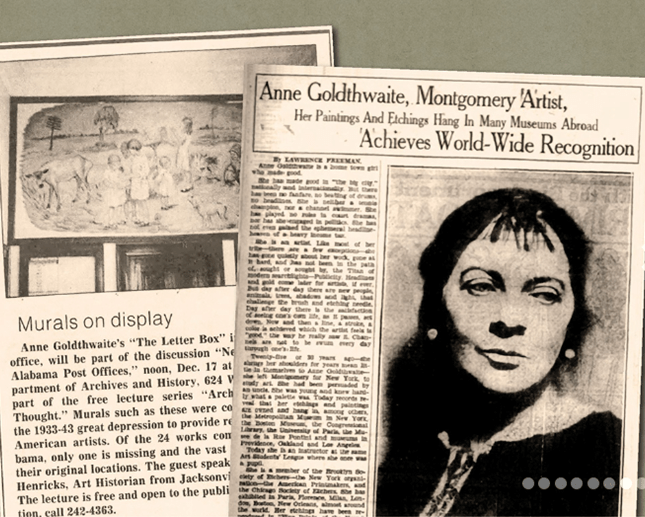

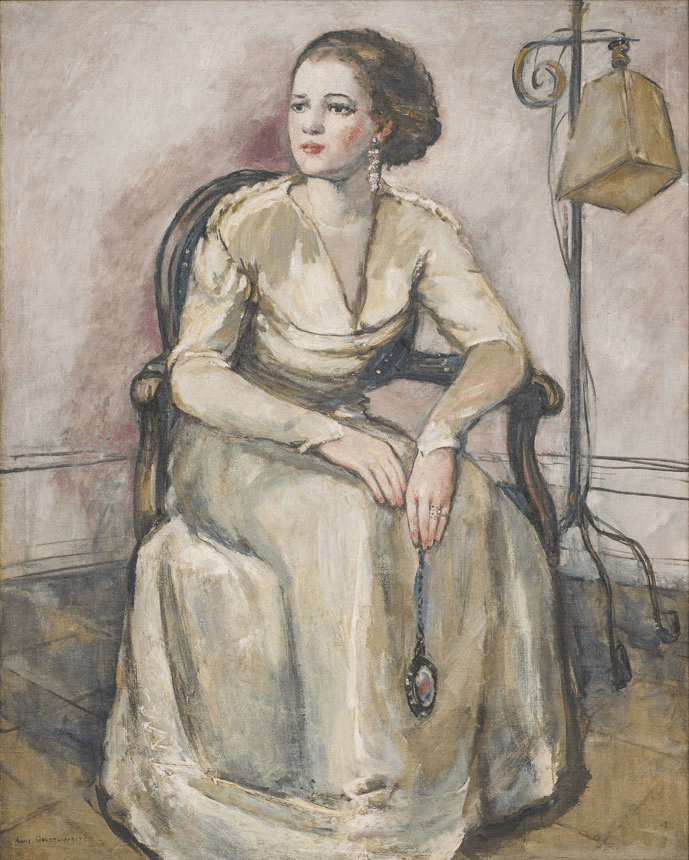

Evangeline Blashfield by Edwin Blashfield (1889)

Evangeline Wilbour Blashfield came from a long line of feminists and suffragists. Her mother, Charlotte Beebe Wilbour, founded and led half-a-dozen societies for the advancement of women, including Sorosis, the nation’s first women’s professional club. Evangeline often wrote about the rights of the poor and the downtrodden. She was able to understand a deep problem that even nowadays troubles her country and politics: that the oppressed, forgotten, and disenfranchised cannot become equal citizens until they have equal voice, dignity, and history. Evangeline was a knowledgeable historian. She understood that remembering rather than forgetting the errors and abuses of the past is the best defense against future abuses of our shared humanity.

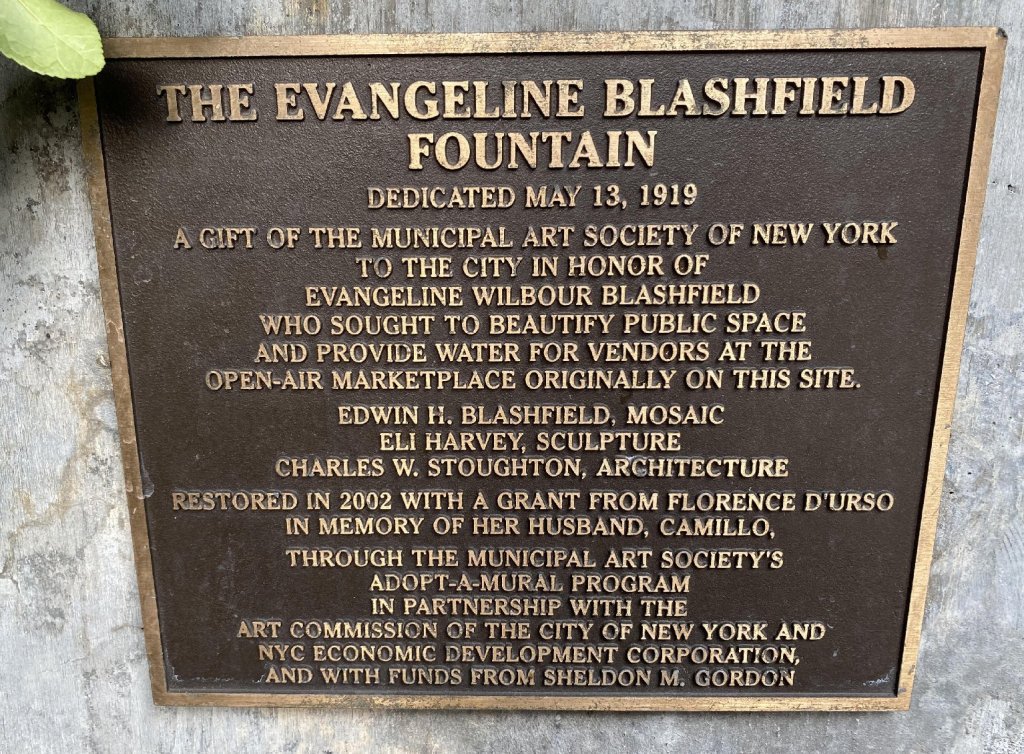

Evangeline Wilbour Blashfield Fountain

A gift of the Municipal Art Society of New York to the city in honor of

Evangeline Wilbour Blashfield who sought to beautify public space and provide water for vendors at the open-air marketplace originally on this site.

Evangeline Wilbour Blashfied died in New York on November 15th, 1918 aged 60. Six months after her death, the Evangeline Wilbour Blashfield memorial fountain was dedicated to her at Bridgemarket, underneath the Queensboro Bridge. She had lobbied for the fountain through her position in the Municipal Art Society. She wanted the vendors (and their horses), who came over the bridge from the farmlands of Queens with their wares, to have fresh water. At the turn of the twentieth century the immigrant sons of toil who kept New York and the nation running trucked their vegetables across the bridge every day to the beautifully vaulted Bridgemarket, but the space outside was a muddy, rutted mess. Evangeline wanted a fountain to be built to beautify this space and to water the horses of the vendors at the market.

In 1928, ten years after Evangeline’s passing, Blashfield re-married. His second wife was Grace Hall. Blashfield had been very active within the art community throughout his life. He served as President of the National Academy of Design, the National Institute of Arts and Letters (1915-16), and the Society of American Artists (1895-6). He was also a member of the Society of Mural Painters, the Architectural League, the Federation of Fine Arts of New York, and the National Commission of Fine Arts. Among his many honours, Blashfield was awarded a Gold Medal by the National Academy of Design in 1934, an honorary membership in the American Institute of Architecture, and an honorary Doctor of Fine Arts by New York University in 1926.

Edwin Howland Blashfield died at his summer home on Cape Cod on October 12th 1936, aged 87.