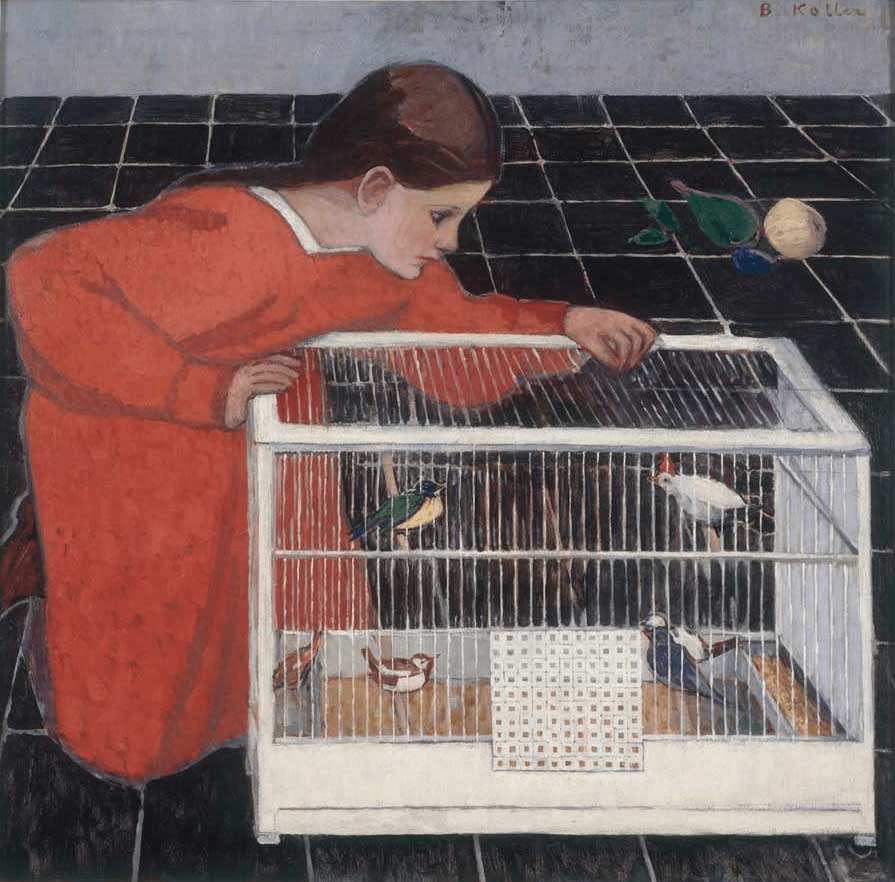

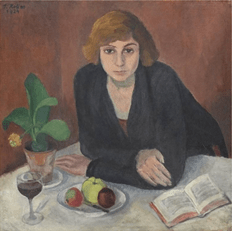

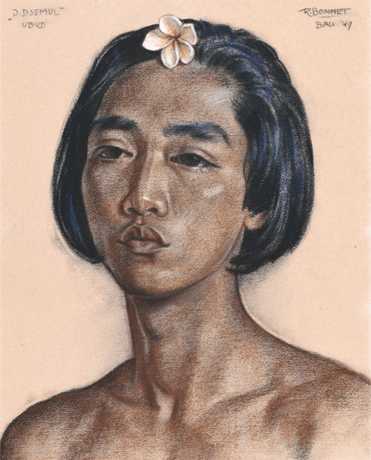

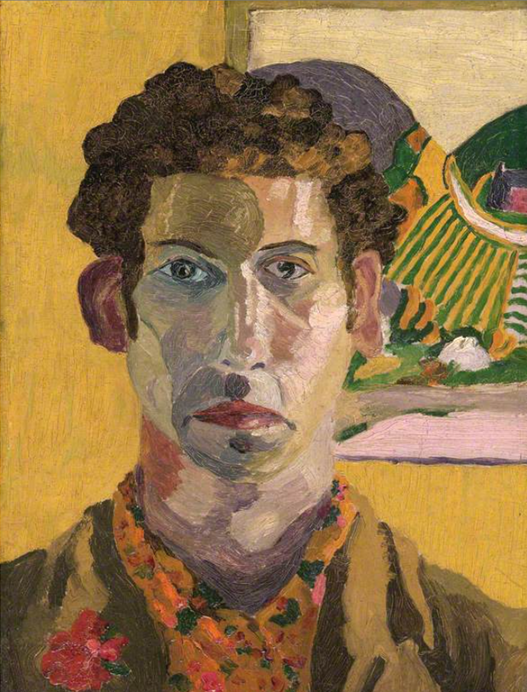

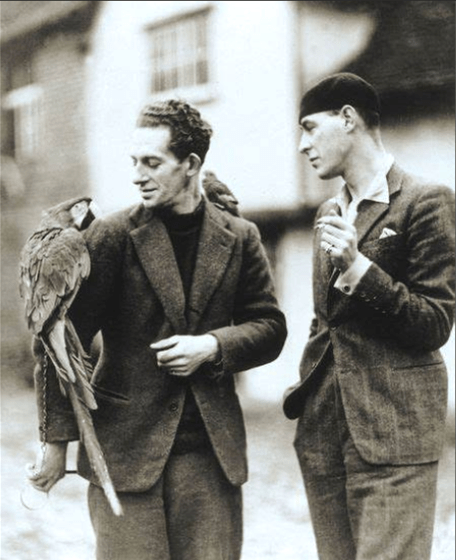

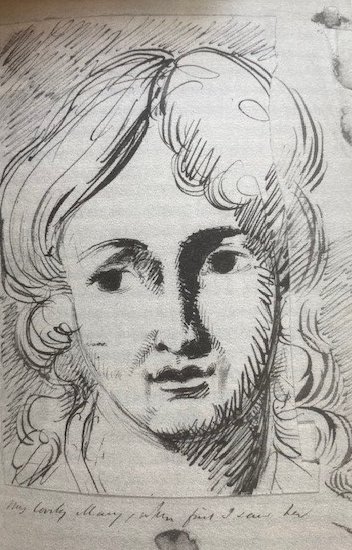

Portrait study of Isabel, by Philip Alexius de László, (c.1909)

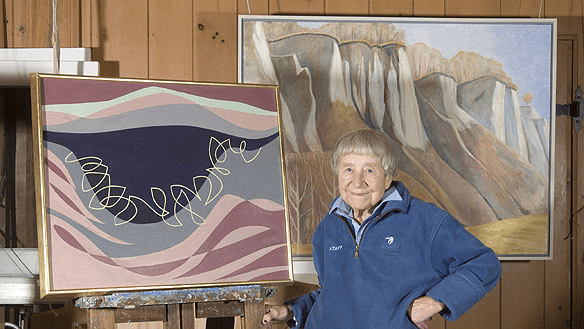

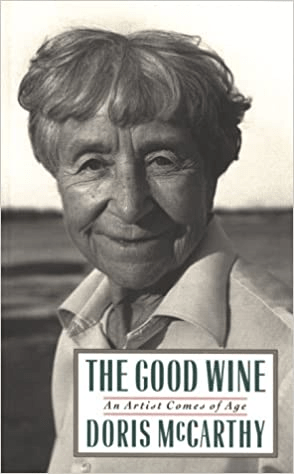

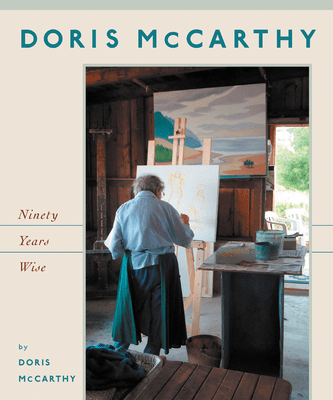

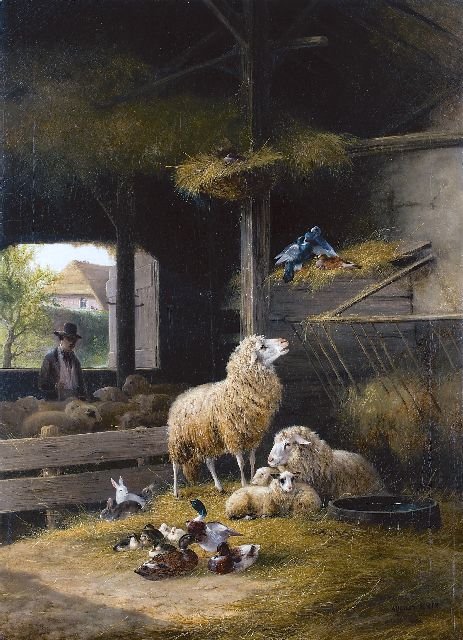

In 1856, John Nott , the Lord of the Bydown Manor estate within the parish of Swimbridge, close to the town of Barnstable in Devon, died childless and his two sisters Elizabeth and Marianne became his co-heirs. In 1838 Elizabeth Nott married Reverend John Pyke, and their son John Nott Pyke, became the heir to Bydown. John Nott Pyke was educated at Eton College and Exeter College, Oxford and was an amateur playwright. In 1863 John Nott Pyke received royal licence to assume the additional surname of Nott, in compliance with the will of his uncle and thus became known as John Nott Pyke-Nott. In 1867 he married Caroline Isabella Ward, a writer and artist. The couple had five children, three sons and two daughters. John Moels Pyke-Nott, the eldest and heir to the estate was born in 1868. Caroline Evelyn Eunice Pyke-Nott was born in 1870 and Isobel Codrington Pyke-Nott was born in 1874 and it is this lady, a painter that is the subject of this blog.

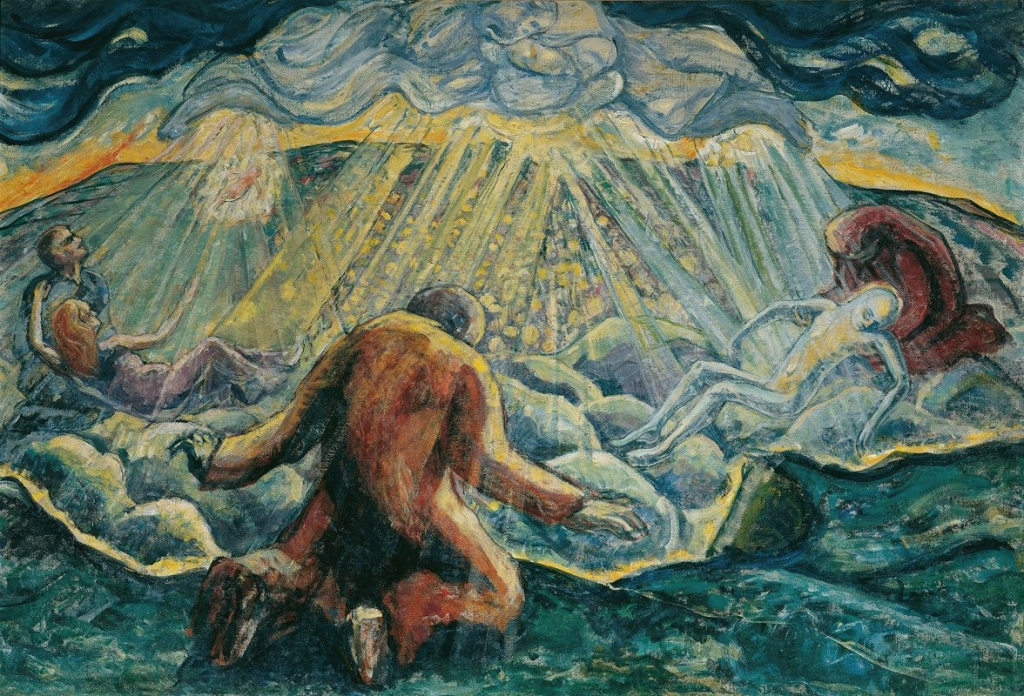

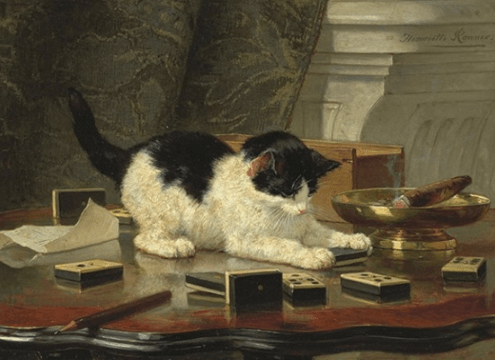

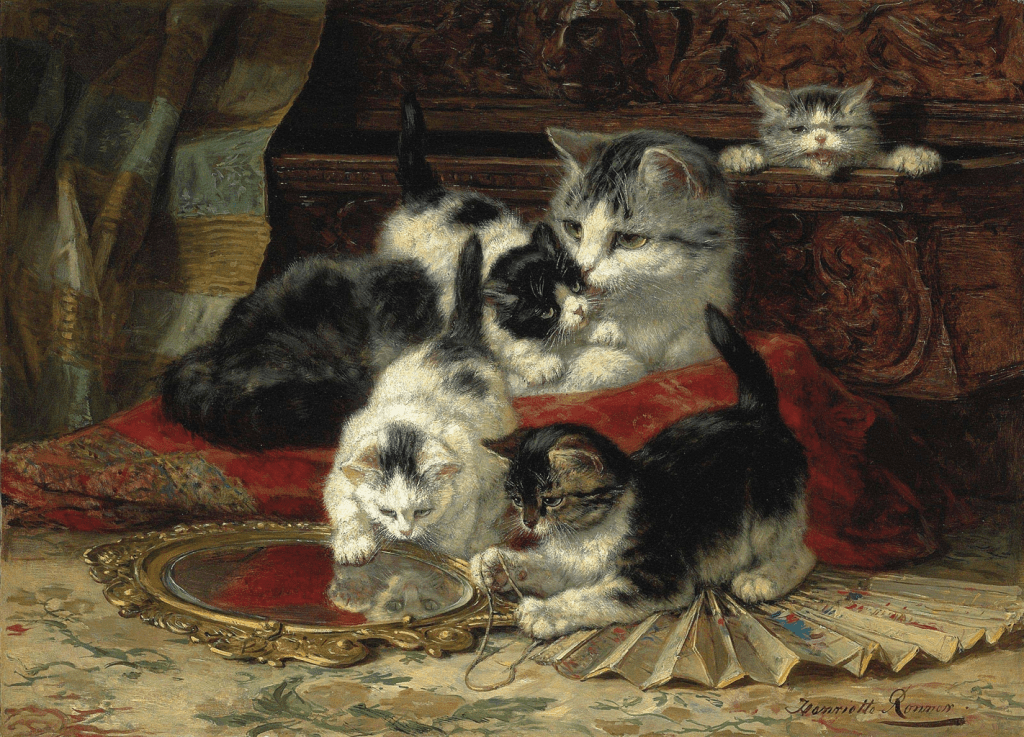

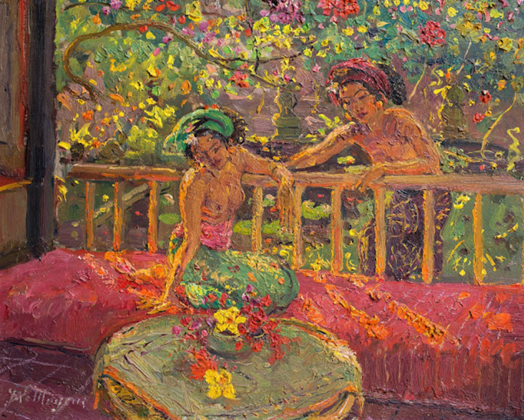

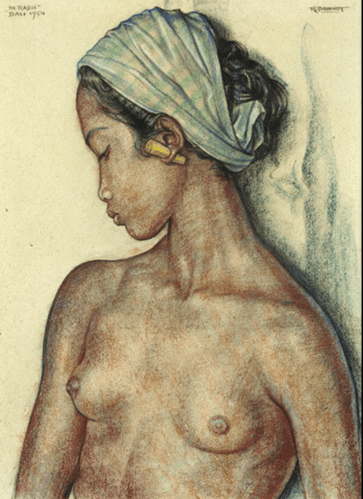

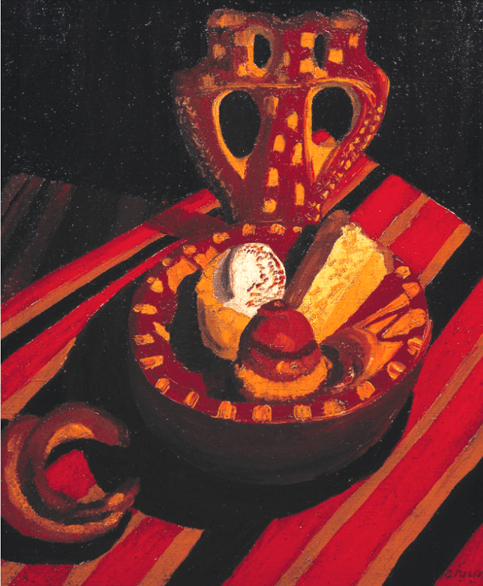

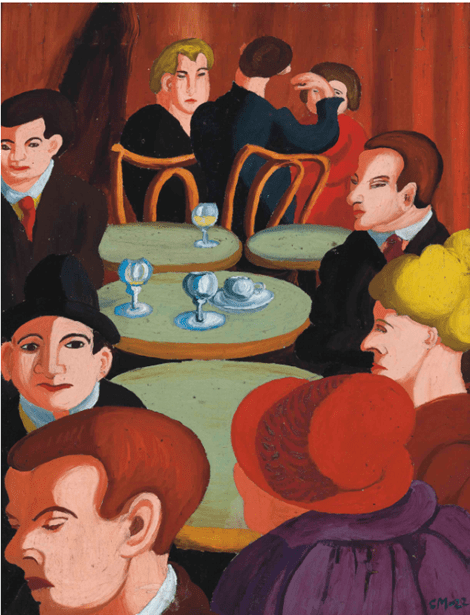

Phoebe by Isabel Codrington

Isabel Codrington Pyke Nott, more commonly referred to as Isabel Codrington, was born on the Bydown estate within the parish of Swimbridge in Devon in 1874. When she was nine years old she and her family moved to London. In 1885 Isobel and her sister Evelyn Caroline Eunice were enrolled at the Hastings and St Leonards School of Art. From there Isobel and her sister attended the St John’s Wood Art School which was a precursor for entry into the Royal Academy Schools which Isobel entered in 1889, aged fifteen. It was also here that her sister Eunice met her husband-to-be, the artist Byam Shaw. Isobel soon displayed her artistic talent and won two medals for her work and she soon began to have her work shown at various exhibitions.

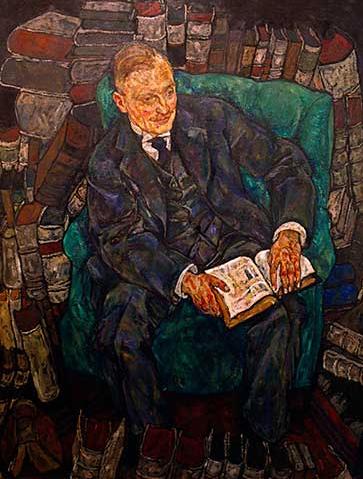

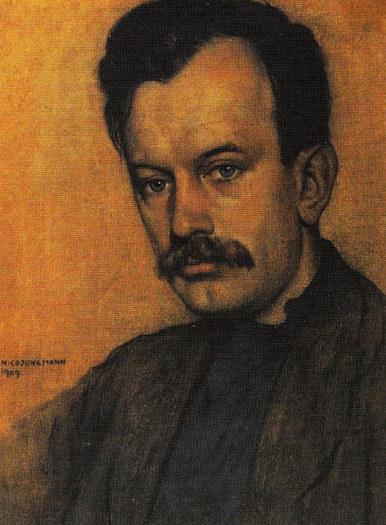

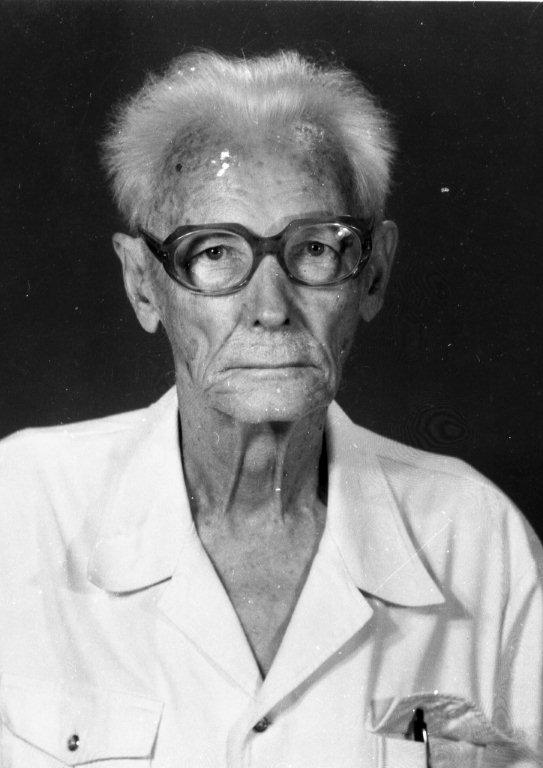

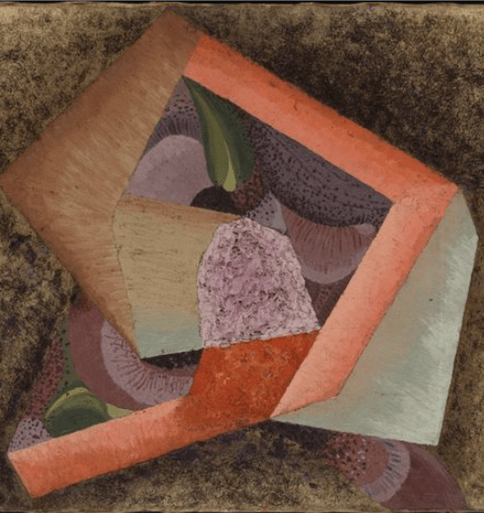

Paul George Konody by William Roberts (1920)

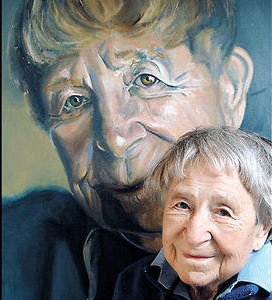

Around the end of the nineteenth century Isobel Codrington met a young and highly motivated Hungarian-born art critic, Paul George Konody who at the time was the editor of The Artist, and later became a regular art reviewer for The Observer and The Daily Mail. The couple fell in love and were married on October 27th 1901 in the romantic village of Porlock, an English coastal village in Somerset. Isabel was twenty-seven at the time of her marriage and her husband, twenty-nine. She was now Mrs Isabel Konody. The couple went on, during the next five years, to have two daughters, Pauline and Margaret.

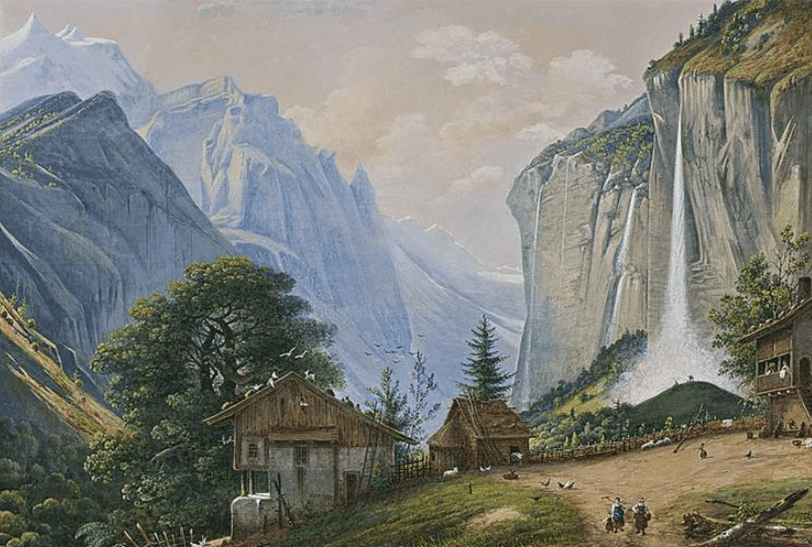

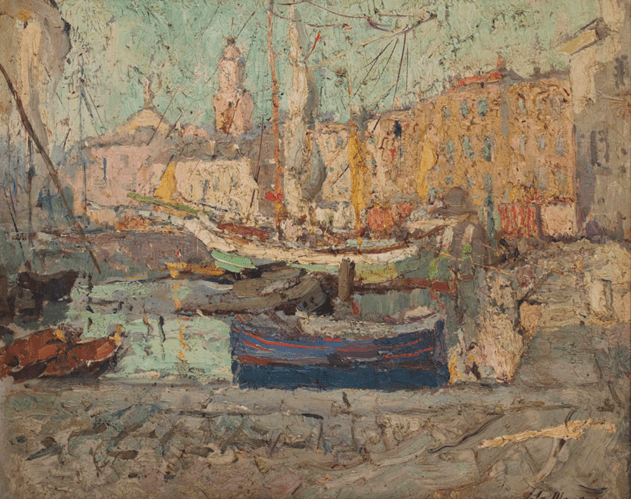

At this time, Isabel’s work featured miniatures and inventive watercolours, one of which won her a medal at the Exposition Internationale d’arte in Barcelona in 1907. Isobel and her husband lived in London and hosted many parties for their artistic and literary friends. Isobel’s husband was a keen motorist and the couple and two male companions, Gustavus ‘Dan’ Mayer, the art dealer, and ‘Pomponius’, the architect, Edwin Alfred Rickards, embarked on an exciting road trip in 1911 driving through France and then down the length of Italy from north to south through the Alps and Apennines, in what Konody described as a ‘noiseless’ thirty-horse-power steam driven landau. Out of this momentous trip Konody published the account of their exploratory journey in a 1912 book entitled Through the Alps and the Apennines.

Mrs Konody sketching an ox-cart at Assisi. Photograph by Gustavus Mayer from P.G. Konody’s book , Through the Alps to the Apennines, (1911)

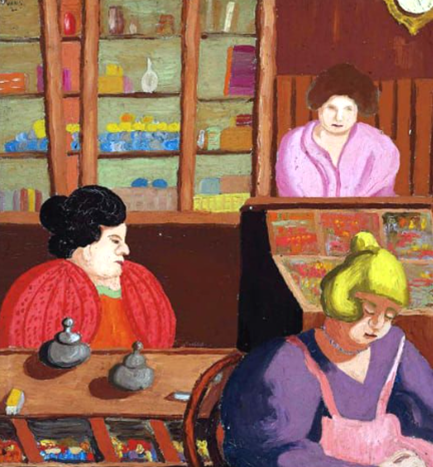

Cantine Franco-Britannique, Vitry-le-François by Isabel Codrington (1919)

Sadly Isobel’s marriage to Paul Konody came to an end around 1912 and they divorced in 1913. That same year, Isabel married Gustavus Mayer, known as Dan, who had been with Isabel and her husband on their Italian road trip. He was a director in the London art dealership, P & D Colnaghi.

The Beggars are coming to Town by Isabel Codrington

Having two young daughters and a new husband to look after curtailed her painting for a few years. She remembered the time she returned to her beloved art in an interview with a reporter in 1918, saying:

“…I felt I would like to begin again…… I had forgotten almost everything…”

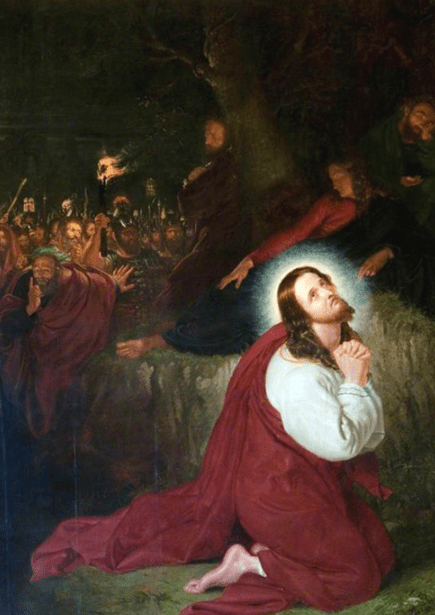

The phrase “getting back on the horse” came to fruition in 1919 when she received a painting commission from the Imperial War Museum for a painting, Cantine Franco-Britannique, Vitry-le-François, which depicted life at a French canteen during the Great War. It is an interior scene of a canteen for French troops and we see soldiers sitting and standing around the tables talking amongst their comrades. In the right foreground we observe one soldier greeting another who has just come into the room. On the extreme left of the foreground, we see one soldier slouched over with his head resting on his arms on a table.

The Shrimp Girl by William Hogarth (c.1745)

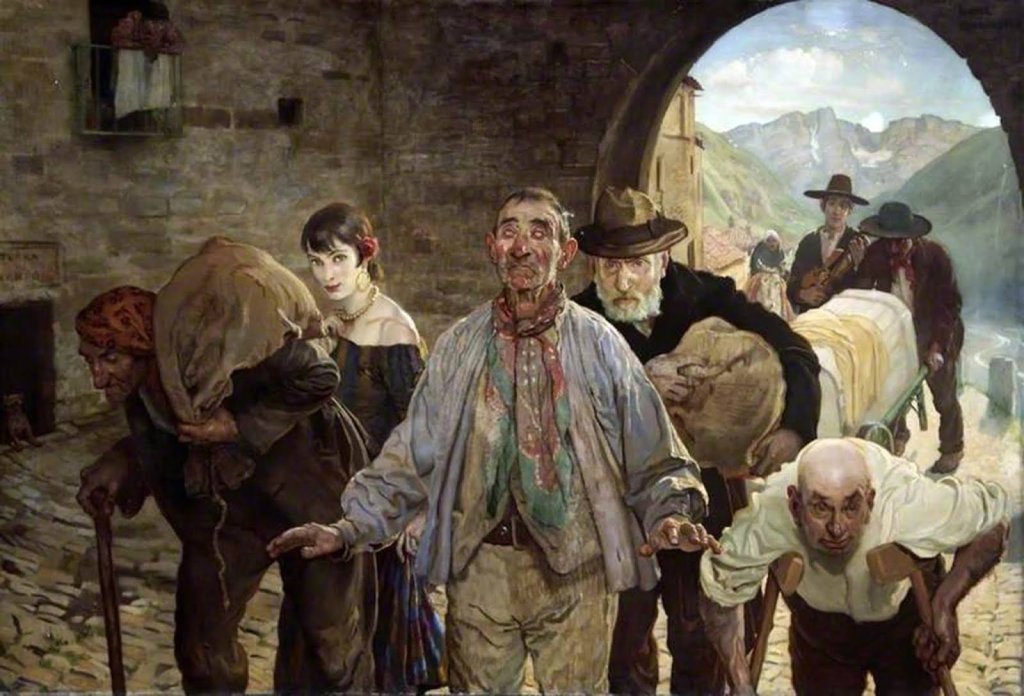

The depiction of Costers, Hawkers and Gypsies became popular around the mid eighteenth century with the likes of William Hogarth’s painting, The Shrimp Girl. The painting was one of Hogarth’s later works and depicts a woman selling shellfish on the streets of London, which was typically a job assigned to the wives and daughters of fishmongers who owned stalls in markets such as Billingsgate. By the 1920s this type of depiction was favoured by the likes of George Clausen, who was one of Isabel Codrington’s most notable teachers.

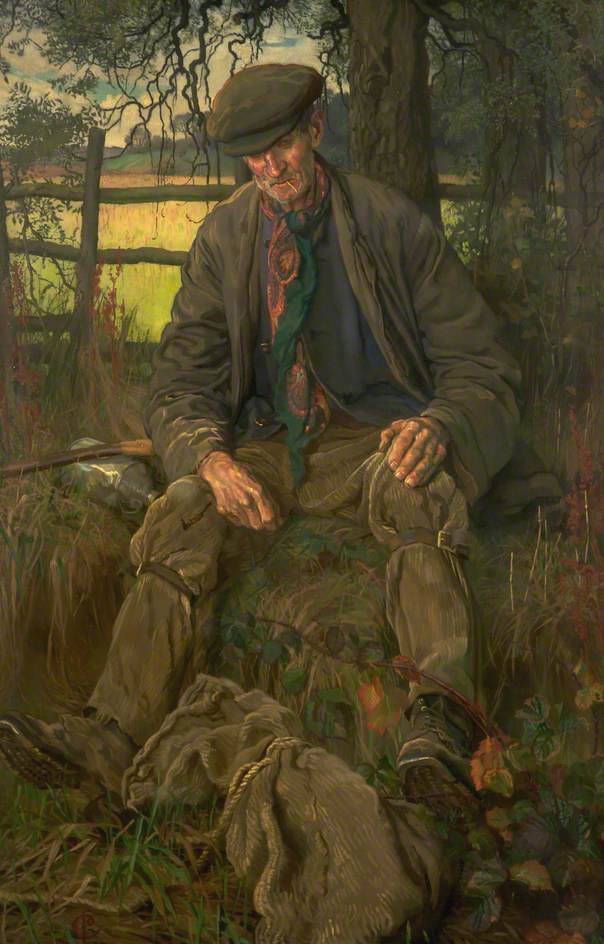

The Old Tramp by Isabel Codrington (1926)

Her painting entitled The Old Tramp was well received by the critics and the art critic of the Colour magazine wrote:

“…At the present time Miss Codrington is among its ablest exponents as can be seen in this outdoor character study which is remarkably naturalistic and full of descriptive detail…”

The article also made reference to the plein air tradition of George Clausen and Bastien-Lepage.

Zillah Lee, Hawker by Isabel Codrington (c.1928)

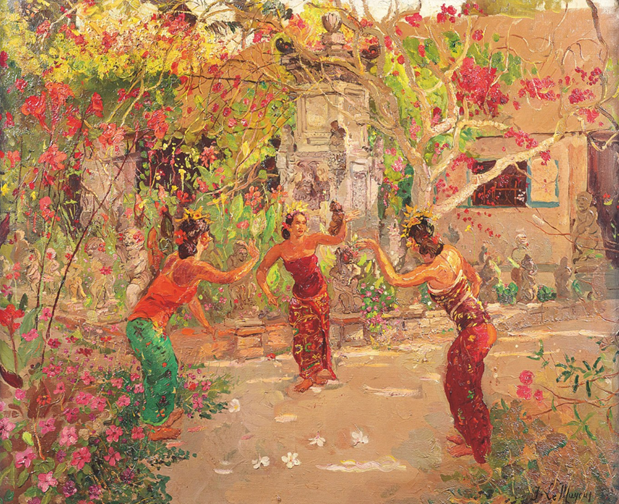

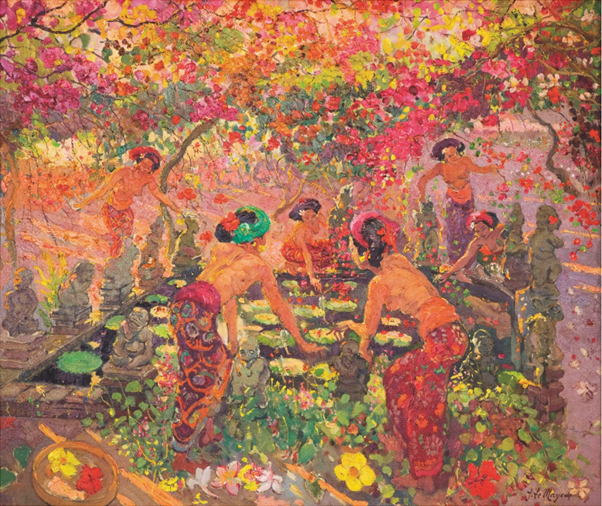

Two years later in 1928 when her painting entitled Zillah Lee, Hawker was shown at the Paris Salon des Artistes Français, similar remarks were made about her depiction of the gypsy woman. One French critic remarked that the depiction of the old woman was ‘sobres, très observés, traduites avec une grande simplicité de moyens, (simple, highly observed and translated with great simplicity of means). The exhibiting of her work that year was the fifth time her paintings had graced the walls of the Salon. From Paris the painting went to London where it was exhibited at the Royal Academy.

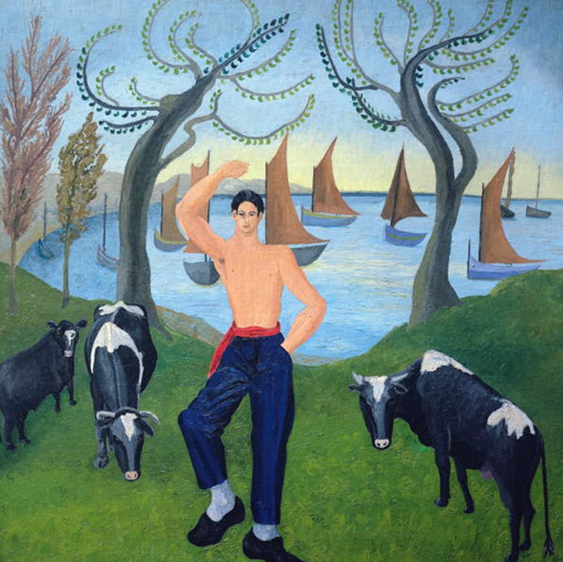

The Onion Rover by Isabel Codrington

In the 1920s Isabel had her work exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy and after 1923, her paintings could be seen hanging at the prestigious walls of the Paris Salon. On one occasion she received a Mention Honorable from the Salon Jury. One of her favourite subjects for her paintings was that of peasant life. She had exhibited works alongside the great George Clausen, one of the foremost modern painters of landscape and of peasant life and maybe it was his influence that influenced Isabel. It could also be, despite her impressive circle of artist friends and the connections she made through her husband’s firm of P &D Colnaghi, that Isabel preferred scenes of peasant life which she would have come across during her travels through France, Spain and Italy. One of her “peasant” depictions was entitled Onion Rover.

The Old Violinist by Isabel Codrington (c.1933)

Fine Prints of the Year was an annual series of books that reported and discussed the etchings, engravings, woodcuts and lithographs published each year between 1923 and 1938 by major artists of the period. Malcolm Salaman, an art critic and Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Painter-Etchers and Engravers, who studied at Slade School of Art and Ruskin School of Art, Oxford, explained in the preface to the 1933 volume of Fine Prints of the Year, why he had chosen to illustrate the distinctive figure of The Old Violinist in preference to Isabel Codrington’s consummate landscapes. He wrote about the subject of the print:

“…He is playing his way slowly along the poor street, his worn fingers touching the strings in no uncertain fashion, though his bowing is not perhaps what it was in his younger and more showy days. But there is something in the tone or the tune that attracts a small boy ambling along with his marketing mother. This etching is suggestive, the face, figure and clothes of the man show wear, but the fiddle is being strummed with a reminiscence that the child seems to recognise…”

Isabel often added distant figures to her etched street scenes, so to enrich the narrative element of the work.

Drowsy Summer Days by Isabel Codrington (c.1935)

In complete contrast to Isabel’s paintings depicting gypsies, beggars and the like, she produced one of her most sensuous works entitled Drowsy Summer Days. Isabel Codrington may well have seen paintings depicting provocative reclining nudes which were popular in the 1920s and 1930s but she has depicted the sleeping female in the most sensitive way.

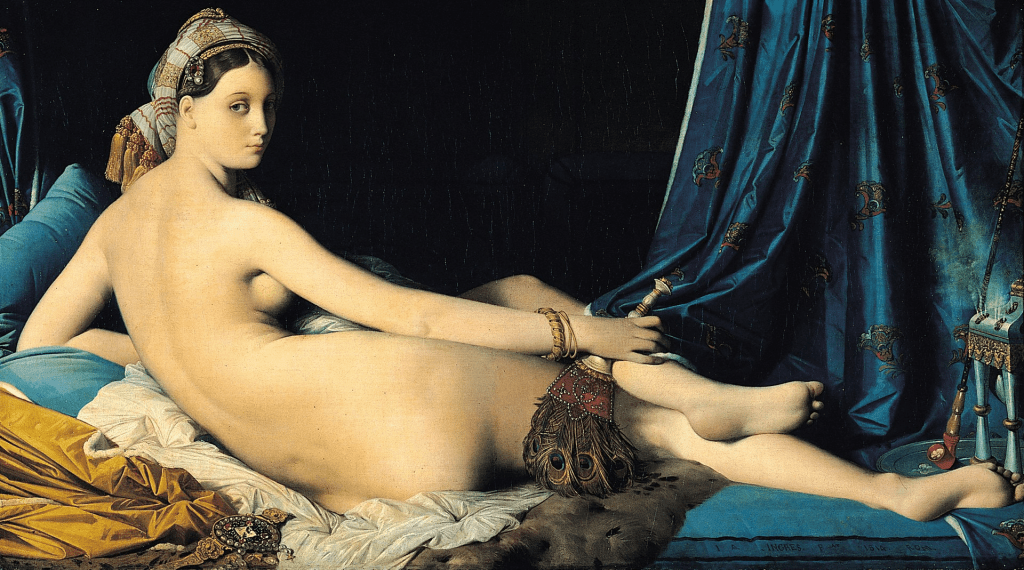

Grande Odalisque by Ingres (1814)

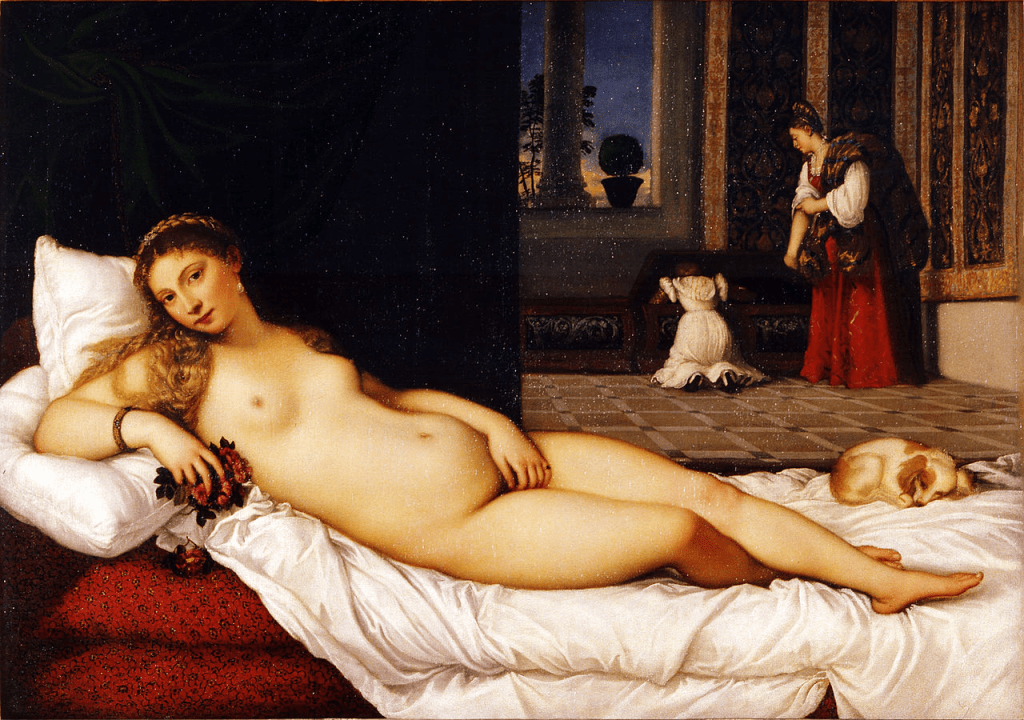

Her model’s sleek torso, pale skin, and the cool, silken cloths and cushions on which she rests, remind us of Ingres’ 1814 Grande Odalisque or the Venus of Urbino by Titian..

Venus of Urbino by Titian (1534)

In Isabel’s painting the woman’s body is bathed in the light from the fire in her boudoir on what appears to be a drowsy summer day. The young woman’s book has been set aside and her arms have fallen by her side, whilst her head has sunk into a silken pillow. The painting was the last one she submitted to the Royal Academy. Alfred Lys Baldry, the English art critic and painter commented on the work saying:

“…. it was an idealized rendering of the female nude as seen by a male painter and the frank fidelity of the female nude of the woman artist who has no illusions about the beauty of her sex…”

Morning by Isabel Codrington (1934)

Similar in some ways and yet in total contrast in other ways is Codrington’s 1934 work simply entitled Morning. It was a masterclass on the use of light and shade. Gone are the silk furnishings seen in her Drowsy Summer Days painting. In this work we see a woman lying asleep in a simple metal bed. Her left arm lies outstretched towards the floor while her right hand clutches the sheets. The room is seedy and an untidy mess. In the room we see a plain wooden chair by her bed, enveloped with her discarded clothing and a melted candlestick. In the foreground, the light from the morning sun streams through a window into the room. A breakfast table can be seen, cluttered with bread, cucumber, a bowl of tomatoes, a half-read newspaper, and a glass of water. The lifestyle of the depicted woman could not be further away from the luxurious lifestyle of the female in the Drowsy Summer Days painting.

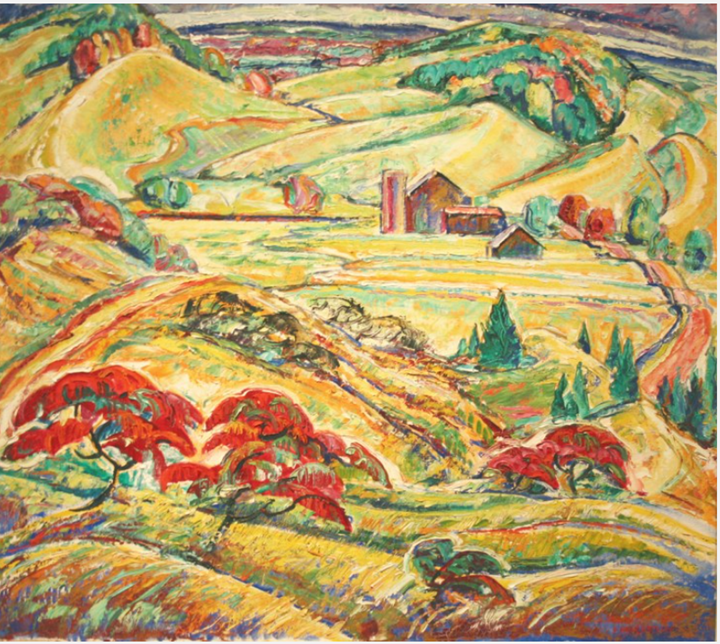

Wild Thyme Farm by Isabel Codrington (1927)

Isabel and her husband, Gustavus Mayer, moved to the village of Woldingham in Surrey, and bought a mock-Tudor mansion named Wistler’s Wood.

Isabel Codrington dominated the British art scene during the 1920s. Her landscape work was outstanding and her painting, Wild Thyme Farm was a prime example of her excellence. The depiction with its foreground field of hay-stooks typifies a series of downland landscapes painted by Isabel on the estate surrounding her home at Whistler’s Wood, a forest in Surrey. The sun shines from the left on to the rolling hills and casts long shadows.

Frank Rutter, a British art critic, curator and activist who was the art critic for The Sunday Times, wrote about Isabel Codrington’s landscape works, saying:

“…since her art is based on simple domestic commodities and the homely landscapes and barns of the southern counties, Isabel Codrington has little need of an interpreter. Her pictures speak for themselves and speak simply but eloquently…”

The Lily Garden by Isabel Codrington (c.1935)

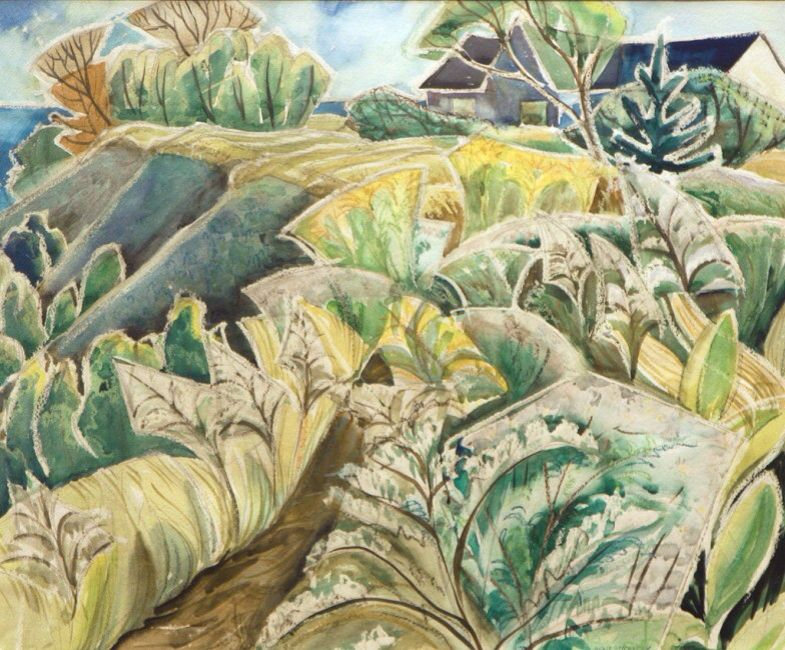

Isabel’s landscape paintings depicting rural scenes around her home, the Mayer estate, at Whistler’s Wood, Woldingham in Surrey, were shown at a 1929 exhibition. During the 1930s, Isabel began to concentrate on etching and an exhibition of her etchings was presented at Colnaghi’s London gallery in 1933.

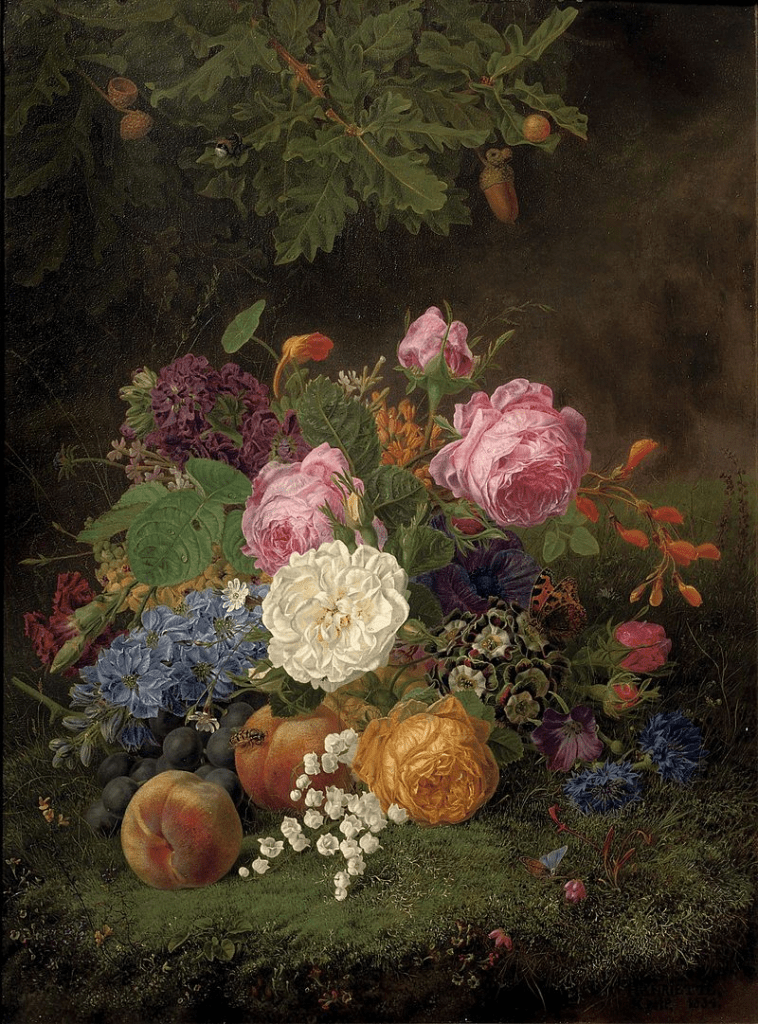

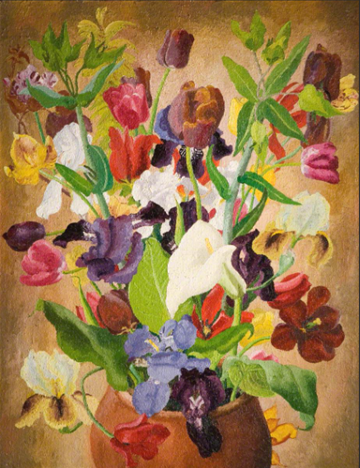

Chrysanthemums by Isabel Codrington

In 1935 she submitted work for the Royal Academy exhibition for the final time. Her final solo exhibition of ‘Flower Paintings’ was held at the Rembrandt Gallery in Vigo Street in November 1935. During the final years of her life, she moved to Devon where she died in 1943, aged 68.

Below are some websites I used when compiling this blog and they will offer you further reading about the life and works of Isabel Codrington.