Jessie Mary McGeehan

Jessie Mary McGeehan was born to Patrick and Mary McGeehan in 1872 in Rawyards, Airdrie, about twenty miles east of Glasgow. She had four younger sisters, Annie Louise, known as Aniza, born on December 24th 1874, Mary Catherine born March 6th 1877, who in September 1904 entered the Order of Sisters of Notre Dame, taking her final vows in December 1914 and becoming Sister Callista. Agnes McGeehan was born April 26th 1882 and she was the one daughter who helped the mother with the running of household affairs. Agnes was the only one of the McGeehan sisters who never went for art training. The youngest sister was Lizzie who was born on May 20th 1883. Lizzie was eighteen when she attended the Glasgow School and remained there for for five years. Lizzie exhibited her watercolours, signing them Phil Winsloe, from 1908 to 1918, the year she died of pneumonia, just thirty-five years old. There was also two brothers Charles Vincent born in 1882 and William born in 1884. However this is the story of the two eldest sisters, Jessie and Aniza, who made names for themselves in the world of art.

Jessie and Aniza’s father was Patrick McGeehan, whose own parents had emigrated from Ireland in the 1820s. He was a grocer and spirit dealer in Black Street, Rawyards, who later became a carriage hirer. Patrick was also a talented musician and amateur artist who must have reached a high standard as his painting The Blasted Oak, Cadzow was accepted by the Royal Scottish Academy in 1879. He was very involved in the town’s community and church life. There can be no doubt that Patrick encouraged his children to progress with their own artistic ambitions.

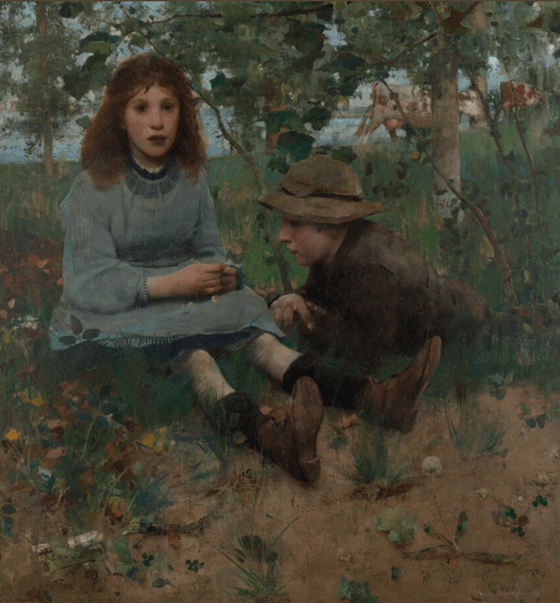

Good Morning by Jessie McGeehan

In the March of 1888, Patrick’s eldest daughter Jessie, still only fifteen years of age, enrolled at the Glasgow School of Art. That September, two of her younger sisters, Annie Louise, known as Aniza, aged thirteen, and nine-year-old Mary Catherine joined her. One would have thought that they would have been too young to study at the Art School but when examining the attendance register of the School it can be seen that there were many other students of that age. It is thought that the deciding factor for their admission was down to them having an older sibling or family member at the school. Jessie and Aniza studied there for seven years but Mary Catherine McGeehan, according to the Art School register, only completed one year before leaving. While studying at the art college the girls won a number of prizes in local competitions and gained free studentships to the school.

The photograph above shows the female students who were attending the 1894/95 session at Glasgow School of Art Archives. Aniza McGeehan is standing immediately above the seated gentleman, Francis Newbery, who was head of the Art School, and her sister, Jessie, is the third lady on the right of Newbery.

Dinan by Jessie McGeehan

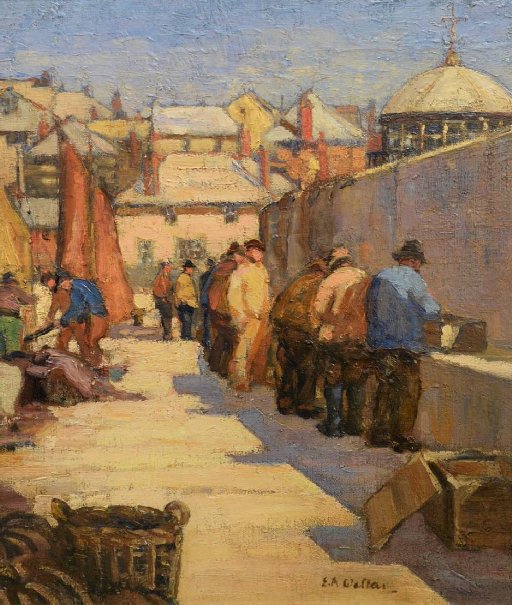

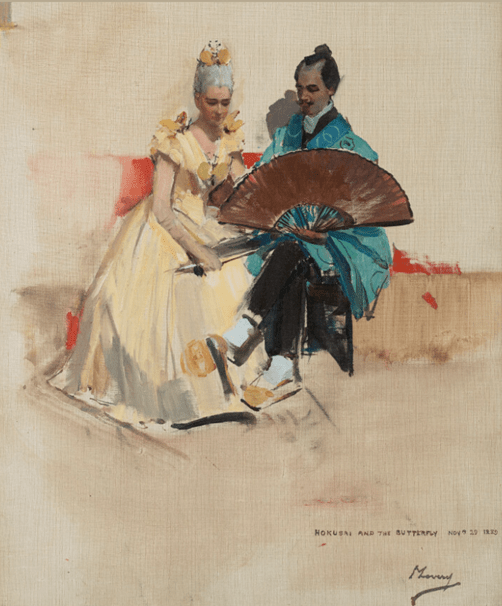

After leaving the Glasgow School of Art in 1895 Jessie continued her studies in Paris. It was around this time that Jessie’s paintings had a “flavour” of France as can be seen in her work entitled Dinan, depicting the Breton riverside town with a view of the river, bridge and buildings. Other paintings of hers depicting the French way of life were entitled Un Bon Coin and Flower Sellers, Paris which were exhibited at the Exhibition of the Royal Glasgow Institute of Fine Arts (RGI). From the last decade of the nineteenth century Jessie’s work, both oil and watercolours, were shown at exhibitions at the Royal Glasgow Institute of Fine Arts, the Royal Scottish Academy and the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool and in 1901 her work was shown at the Royal Academy, London.

Harvesting Plums by Jessie McGeehan (1932)

In 1897 Jessie set up her own studio at 134 Bath Street, Glasgow which for a time she shared with her sister Aniza. Shortly after the turn of the century Jessie’s artwork was being appreciated throughout Britain and abroad. In the art magazine, The Studio, there was an article about female artists and part of which was dedicated to Jessie:

“…In any notice of the lady painters of Glasgow, mention must also be made of Miss McGeehan’s bold and striking work. She is an ambitious artist whose pictures improve steadily from year to year; she evinces considerable skill in brushwork, and much that is fine and poetic in the inspiration of her work…”

On a Dutch Canal by Jessie McGeehan

During the early 1900s, Jessie spent time in Holland as many of her works, which appeared in exhibitions between 1906 to 1913, featured Dutch subjects. Her reputation as a talented young artist grew and the Scottish newspaper, the Scots Pictorial wrote about her growing reputation in the art world by 1919:

“… Jessie McGeehan – ‘One of our youngest Painters whose work has earned for her a high place among British Artists. Trained at the Glasgow School of Art, and in Paris, where she enjoyed the friendship of some of the greatest painters and sculptors of the age, she has added to this training by travel and an exhaustive study of the treasures in the great European galleries. Miss McGeehan contributes to the Royal Academy and other important art exhibitions…”

Children playing on the Beach by Jessie McGeehan

The year 1915 was the beginning of a sad time for the McGeehan family. That year their son, William who was just thirty-one years-old was reported missing presumed dead, while serving in France with the King’s Own Scottish Borderers. Three years later in 1918 his brother, Charles Vincent, a joiner who was only thirty-six, died in the Western Infirmary, Glasgow and his younger sister Lizzie died of pneumonia, aged 35. One year after their deaths and after forty-eight years of marriage, Patrick’s wife Mary died at their home in Montgomerie Street, Maryhill, Glasgow. Jessie’s father Patrick died on May 3rd 1924.

Glass mosaic in St. Augustine’s Church by Jessie McGeehan

Jessie McGeehan created a glass mosaic panel for St Augustine’s Church in Langloan, Coatbridge. She also created a glass mosaic in fourteen panels depicting the Stations of the Cross for St Aloysius Church in Garnethill as well as undertaking work for St Mary’s Church in Lancashire.

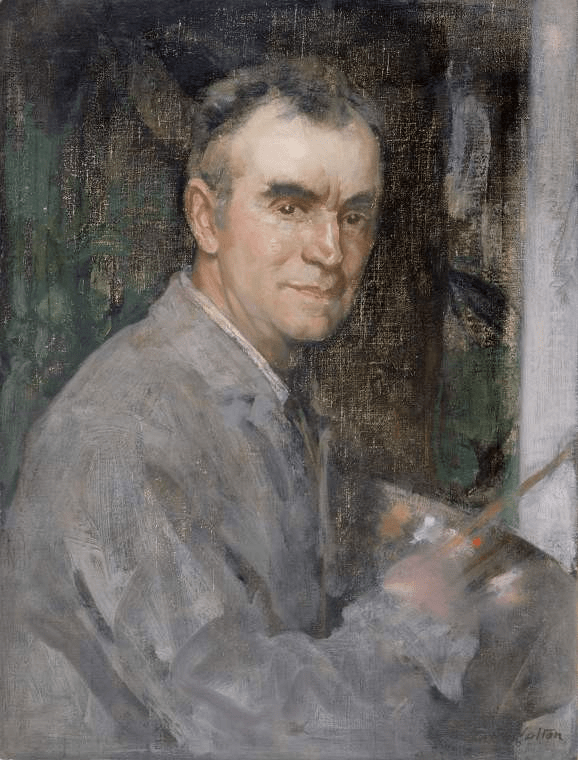

Aniza McGeehan by Jessie McGeehan (1929)

Jessie McGeehan’s 1929 oil portrait of her sister Aniza is in the North Lanarkshire Museums collections. This was one of two oil paintings exhibited in the 1929 Walker Art Gallery Autumn Exhibition. At the same exhibition Aniza exhibited a bronze bust of her sister, Jessie.

Running parallel to Jessie’s artistic life was her sister Annie Louisa (Aniza) artistic journey. Aniza was the second of eight children, born on December 24th 1874. She was two years younger than Jessie but, like her and her younger sister Mary, she attended Glasgow Haldane Academy Society of Arts, better known simply as the Glasgow Art School. Aniza’s time at the art school was one of great success, winning a local art scholarship, and in 1895 she was joint winner of the Haldane Travelling Scholarship which came with a £50 prize and with this she was able to afford a trip to Paris in 1896, where she established her own studio and enrolled at the Colorossi Academy. She began to exhibit her work, paintings and sculptures, and in 1897 she had her sculptured bust of Lizzie Bell shown at that year’s Glasgow Fine Art Institute exhibition.

Ferry on the River Dordogne by Jessie McGeehan

Around this time, her father sold his licenced grocery business in Coatbridge and moved to Glasgow. Aniza left Paris and returned home to Glasgow where she shared a studio at 134 Bath Street with her sister, Jessie. She had her portrait of school inspector Dr Smith shown at two exhibitions in 1899. The art critics stating that the portrait was one that evoked “masculine strength” which was in complete contrast to her sculpture work, a bust of Mrs D. Campbell Rowat, which was hailed by the critics as “delicate and refined”.

A Day at the Dunes by Jessie McGeehan

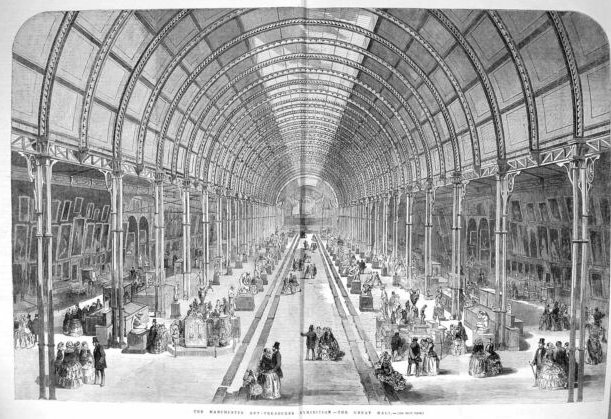

Towards the late 1890s, Aniza received the commission for ten sculptures for Pettigrew and Stephens’ Store, Sauchiehall Street, Glasgow and according to her family she barely had time to finish the commission before her marriage in St Aloysius Church, Garnethill on June 12th 1900 to Vincent Murphy, a timber merchant from Liverpool. The service was conducted by her uncle, Father Charles Brown. Clearly Aniza’s talent had been recognized by many of the leading figures in the Glasgow Art World.

Pettigrew and Stephens’ Store, Sauchiehall Street, Glasgow .

Sadly, this magnificent building, which encompassed many of the outstanding talents in Glasgow, was demolished in 1974. Fortunately, Roger Guthrie, a leading member of the Glasgow conservation movement,managed to save two of Aniza’s sculptures. One was gifted to The Hunterian Museum and the other to the Scottish Amicable Building Society in Stirling. Aniza moved to Waterloo Park in Liverpool which at the time had a number of Scottish families living there. Vincent and Aniza went on to have four children, but only John Vincernt and Marie Louise (Marielle) survived childbirth. Despite the work involved in raising a family she continued with her sculpture work and in 1903 had one her bronze works, Monsignor Nugent, exhibited at the Royal Academy, London.

Learning to Walk by Jessie McGeehan

In the mid-1930s, Jessie had moved to 152a Renfrew Street, which was to remain her studio and home for the rest of her life.

Vincent and Aniza flanked by their son John Vincent and their daughter Mariella

Sadly, Aniza’s daughter Marielle died of pneumonia, when she was only nineteen years of age. Following her marriage Aniza continued to exhibit and take commission work, but soon this became too much due to family commitments resulting in her exhibiting less frequently than Jessie.

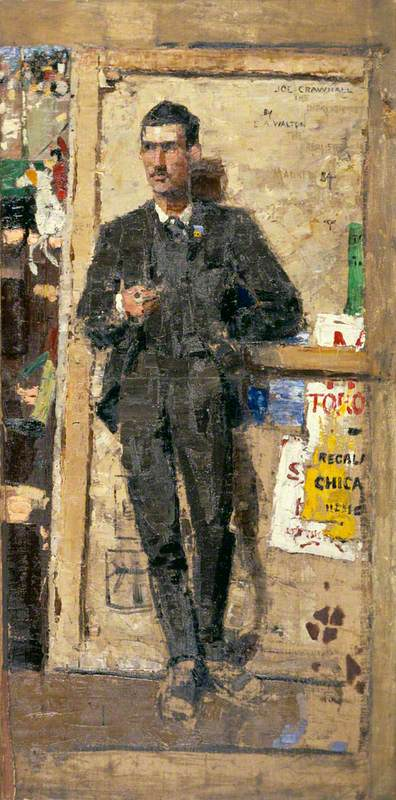

Annie Louise (Anzia) McGeehan

Anzia McGeehan died in September 2nd 1962, aged 87.

Jessie McGeehan died in Glasgow in 1950, aged 78

Information for this blog came from the usual internet sources plus:

The Parish of St Augustine Coatbridge website – A Family of Artists.