The first time I featured a painting by William Dyce was over twelve months ago (My Daily Art Display, May 14th 2011) when I looked at his painting Pegwell Bay, or to give it its full and bizarre title, Pegwell Bay, Kent – a Recollection of October 5th 1858. To find out why the painting had such a strange title you will have to check back on the earlier blog.

William Dyce was born in Aberdeen in 1806. His father was a fellow of the Royal Society and an eminent physician. Dyce attended the Marischal College, which is now part of the University of Aberdeen. He trained as a doctor before reading for the church. However the course of his life changed when aged nineteen he decided to become an artist and enrolled at the Royal Scottish Academy Schools in Edinburgh and later as a probationer at the Royal Academy of London. At the age of nineteen he made his first trip to Rome and stayed there for nine months studying the works of the great Masters such as Titian, Rembrandt and Poussin. He returned to Aberdeen but the following year he went back to Rome and this time stayed for eighteen months. During this second visit to the Italian capital he met the German painter, Friedrich Overbeck, who was one of the leading artists of the Nazarene Movement. The Nazarene Movement was made up of a group of early 19th century German Romantic painters who aimed to revive honesty and spirituality in Christian art. The name Nazarene came from a term of derision used against them for their affectation of a biblical manner of clothing and hair style.

By 1829 Dyce was back in Scotland and settled in Edinburgh for several years. To survive financially he would carry out many portraiture commissions but his main love was his religious, history and narrative paintings. In 1837, he was appointed Master of the School of Design of the Board of Manufactures in Edinburgh and produced a pamphlet on the management of schools like the one he was working at and this was well received, so much so, that he was transferred to London as superintendent and secretary of the recently established Government School of Design at Somerset House, which was later to become the Royal College of Art. In 1844 he was appointed Professor of Fine Art in King’s College, London, and became an Associate of the Royal Scottish Academy, and in 1848 elected to become a Royal Academician.

In 1850 Dyce married Jane Brand who was twenty-five years younger than him. They went on to have four children. He died at Streatham, Surrey in 1864, aged 58.

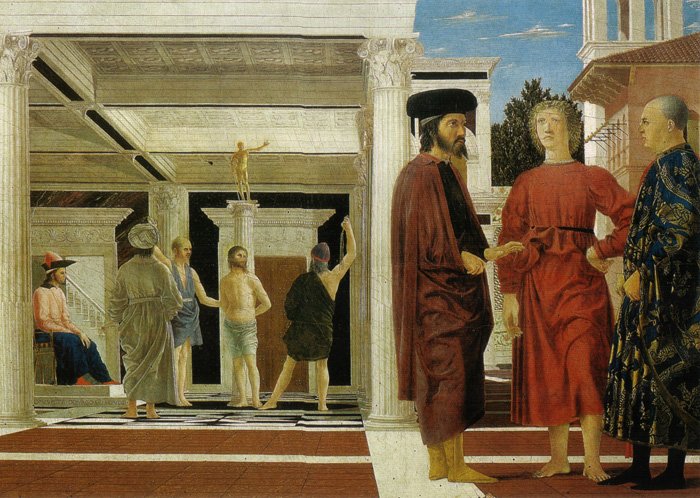

Today I am looking at a completely different type of painting by the artist in comparison to his seaside painting, Pegwell Bay. This is a religious painting entitled The Meeting of Jacob and Rachel. There were about four versions of this work by Dyce, each of different size and with minor alterations but this one, which was completed by him in 1853, is now housed in the Kunsthalle in Hamburg. This was the original work and the only one which had a vase resting on the edge of the well. The painting proved so popular with the public that Dyce commissioned Holman Hunt to make copies of it.

The painting is based on a story from the Old Testament book of Genesis (29: 9-14):

9 While he was still talking with them, Rachel came with her father’s sheep, for she was a shepherd. 10 When Jacob saw Rachel daughter of his uncle Laban, and Laban’s sheep, he went over and rolled the stone away from the mouth of the well and watered his uncle’s sheep. 11 Then Jacob kissed Rachel and began to weep aloud. 12 He had told Rachel that he was a relative of her father and a son of Rebekah. So she ran and told her father. 13 As soon as Laban heard the news about Jacob, his sister’s son, he hurried to meet him. He embraced him and kissed him and brought him to his home, and there Jacob told him all these things. 14 Then Laban said to him, “You are my own flesh and blood.”

This painting, Meeting of Jacob and Rachel, depicts the point in time just before Jacob kissed Rachel, and as the biblical text quotes the experience was so memorable, he lifted up his voice, and wept. Jacob had fallen in love, at first sight, with this beautiful young woman, when he saw her standing at the well about to give water to her father’s flock of sheep. Look at the way Dyce has portrayed Jacob. The young man having just cast his eyes on his cousin is besotted with her. He leans towards her almost balancing on one leg. Look at his demeanour. Look at the intensity of his expression as he looks into Rachel’s face. Look at his eagerness. His emotions seem to be getting the better of him. He clutches Rachel’s right hand and press it against his heart. Maybe he wants her to feel how it is beating wildly. His left hand rests on the nape of her neck. He caresses her neck gently and at the same time his hand will guide her face towards his so that he may kiss her. Now look at Rachel. See how her expression differs from that of Jacob. Her eyes are cast downwards in a gesture of modesty or is it coyness? She cannot meet Jacob’s gaze. The top half of her body leans away from Jacob and she steadies herself by placing her left hand on the well.

So does this meeting of man and woman result in a happy ending? Well yes and no! Rachel’s father, Laban was quite cunning and realised that Jacob was a young and strapping lad who could help out on the farm and so he offered him the hand of Rachel in the future, providing he would work for him. Jacob agreed and worked for Laban for fourteen years without payment in the hope of getting the father’s blessing for his marriage to his daughter. Then Laban made another condition for this marriage. He wanted Jacob to first marry Rachel’s elder sister, Leah, after which he would be able to have Rachel as his wife.

So this is not just a story about young love but also a story of patient love and the way Jacob was willing to wait for Rachel. This may have been uppermost in Dyce’s mind as it mirrored his relationship with his wife-to-be Jane Bickerton Brand who was born in 1831, for he was made to wait for her hand in matrimony as she was so young when they first met and the age difference of twenty-five years obviously further concerned her father. William Dyce did wait and they did marry, so all ended happily.