……………….Cecilia Beaux finally returned to Paris in December 1888 after her summer in Concarneau and her six week European journey and the first thing she had to contend with was to find some new accommodation. Her one priority was that her new “home” had to be better than the dismal and dire Pension Villeneuve which she and her cousin May Whitlock had had to put up with on their arrival from America in January. They eventually settled for a “room-only” fifth-floor attic apartment in a Latin Quarter maison meuble (furnished house) at 30 rue Vaugirard, situated in the 6th arondissement across the road from the Luxembourg Gardens. Cecilia was delighted with her new home, writing:

“…There were five flights for us, but easy, broad, spotless, and without taint of late decades. I would like to boast openly that I have lived in an attic in Paris, a tiny chamber in the mansard, with a dormer window opening its croissee eastward and sunward. The window would hold a plant or two, and outside was the leaden ledge that took the rain on stormy days. Leaning out one could look down upon the Senate, grey and dignified, and the Luxembourg Gallery was very near. The iron railing of the garden was across the way…”

However, it was still winter, still cold and the accommodation was still damp so one of her first purchases was a stove, for which she paid four francs.

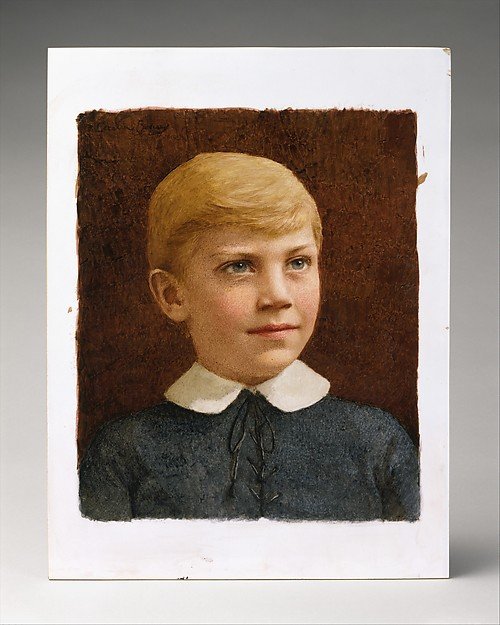

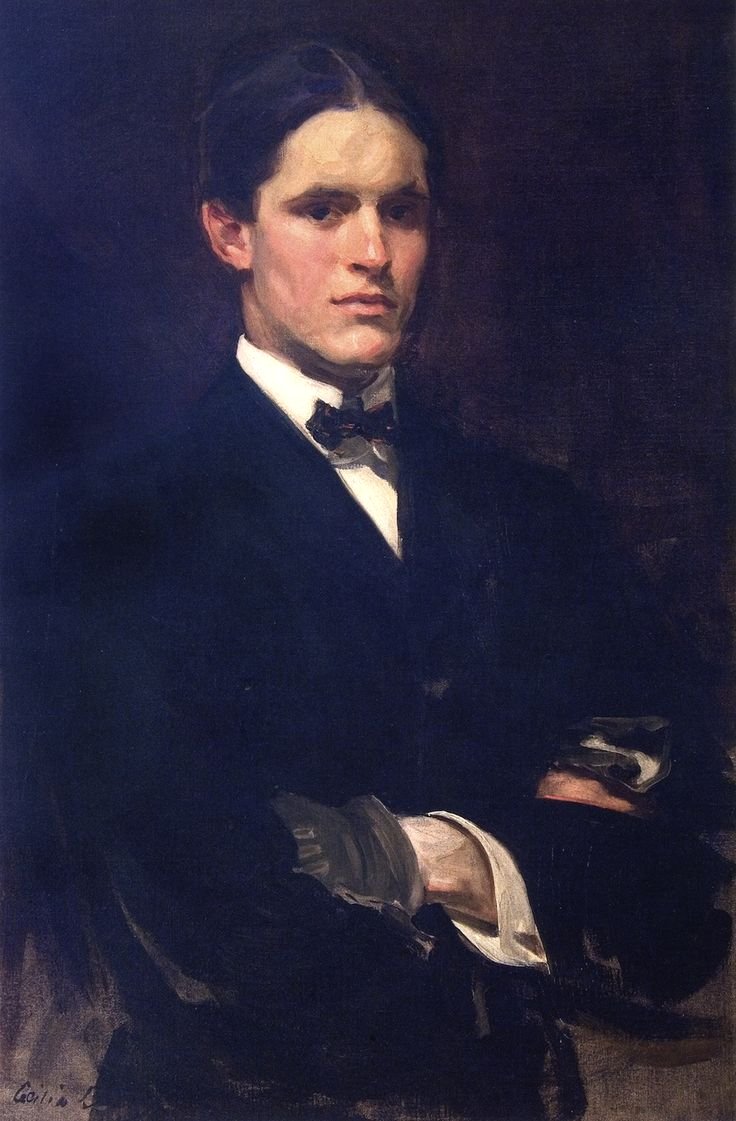

(Cecilia’s nephew)

Cecilia returned to the Académie Julian to study art but this time she attended the original branch of the academy which was at the Passage des Panoramas, which meant she had to make the two-mile journey crossing the Seine each day. It is interesting to read in her 1930 autobiography, Background with Figures, that she was less than enamoured with the teaching at the academy and although she could have attached herself to an atelier headed up by a well-known artist she was not convinced of the benefit of such a move. She wrote:

“…I might have delivered myself, of course, to an individual master. There were several of high repute who admitted disciples. By an instinct I could not resist, I shrank from the committal, although there would have been contacts resulting from it of high value and interest. I saw no special direction in any exhibited work (I fear to say it), among the living, that I felt like joining…”

Cecilia was also unhappy that there were few critiques by the tutors which would have given her some constructive criticism. All the tutors would tell her that she should just “keep on as I was going”. It was not that she was simply negative about the teaching at the Julian for she had definite ideas of how art should be taught and how the tutors should act:

“…What the student above all needs is to have his resources increased by the presence of a master whom he believes in, not perhaps as a prophet or adopted divinity, but one who is in unison with a living world, of various views, all of whose roots are deep, tried, and nourished by the truth, or rather the truths that Nature will reveal to the seeker. He is the present embodiment of performance in art, better called the one sent, representing all. He is serious, quiet, a personality that has striven…”

Cecilia’s room in rue Vaugirard was too small for it to be used as a studio and for her a studio was a primary requisite not just to carry out painting but it was a place for quiet contemplation. With that in mind she managed to secure a nearby small ground-floor working place at 15 rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs which was situated at the southern end of the Luxembourg Gardens. Later Cecilia and her cousin and companion, May Whitlock would give up their room at the rue Vaugirard house and move their belongings into the studio.

In May 1889 Cecilia made a solo trip to England. She had been invited by her one-time Philadelphia friend Martha Haskins “Maud” du Puy, now Mrs Maud Darwin, to come up to Cambridge and stay with her, her husband George Darwin, who was the eldest son of the naturalist, Charles Darwin, and their four children. George Darwin was the Plumian Professor of Astronomy and Experimental Philosophy at the University of Cambridge and the family lived at Newnham Grange, which was situated in an idyllic location perched on the banks of the River Cam. Cecilia had to endure a very rough Channel crossing from Dieppe to Newhaven and then a long train journey through London to Cambridge. However, despite the inauspicious start to her English adventure, her short stay at Newnham was all she could have hoped for. Beautiful house to stay in with a comfortable bed, a completely different scenario in comparison to her room in Paris. In her autobiography she remembered her first morning at Newnham Grange:

“…My first waking in the big, chintz-hung guest-room at Newnham Grange is one of the jewel-set markers of memory………… The sun poured in, and through its beams I could see across a meadow and under huge trees. Another window was hung, without, by a rich drapery of lilac wistaria, in full bloom, and when I sprang from my bed and put my head out, there was a cherry tree full of ‘ripe ones,’ just outside, also bird song; and a robin, making the best of the feast, superseded the cuckoo, and children of English voice and speech were in the garden below…”

She also had a taste of university and English countryside life with an invite to dinner at the Vice Chancellor’s Lodge, Sunday morning service at King’s Chapel and even a visit to Charles Darwin’s eighty-one-year-old widow, Emma, who was Cecilia’s friend’s mother-in-law. She even was invited to the hallowed Master of Trinity College Cambridge’s garden party, remembering the event well:

“…An English garden-party differs from all others especially in the domain of the University. The Master of Trinity, who is the King of Cambridge, has a garden which occupies one bank of the river for a long distance. Acacias in full bloom hang over the wall during May week, tall dark yews associating as background. The Master himself, large, brown-bearded, and urbane, looked his part to perfection, and I was proud to have a share of his gracious attention…”

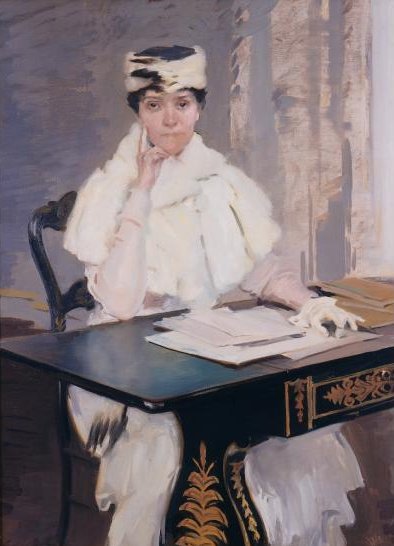

Such was the frequency of invitations to lunches and dinners that Cecilia hardly had time to think about sketching and painting but she did complete one work, a pastel portrait of her host Maud. Maud’s husband George was made Knight Commander of the Bath in 1905, and so the title of this portrait is now known as Lady George Darwin.

Cecilia and May Whitlock cancelled their plans to return to America and instead went to Cambridge in June, where they were to have stayed as guests of George and Maud Darwin, not in the main house but in The Mill, a small residence at the end of the garden of Newnham Grange. However Cecilia decided as it may not have been big enough for two ladies Cecilia and Maud took lodgings, at Ashton House, a small brick dwelling in a shady street, only a stone’s throw from Newnham and used The Mill as her artistic studio.

After that second visit to Cambridge, Cecilia left the comfort of Newnham Grange and returned to Paris only to find that her cousin had vacated their fifth-floor attic room and moved all their possessions and clothes into Cecilia’s small one-room studio with skylight. This was now to be their living quarters, their bedroom, as well as Cecilia’s studio. It was a terrible shock to the system for Cecilia who had just sampled the height of comfort in Cambridge. To make things worse for her and May, as summer approached, the once cool room had become a “hot-house” as the intense sunlight streamed through the skylight. Reading a passage in her biography, one can be in no doubt as to how Cecilia regarded her new “home”:

“…The circumstances of my return to Paris should be mentioned only by way of warning and contrast, and I shall always regret that I returned to the adored place, by way of my own blunder and a very squalid experiment. When I entered the shaky door of the studio, I found it filled with a helter-skelter collection of our belongings. There had been no preparatory cleaning or arranging. A bed had been put in. The toilet arrangements were simple, but for use required a complicated process. A tin basin, which I had used for washing brushes, was uncertainly disposed on the corner of the bookshelf, the soap saucer scarcely holding beside it. A chair-back was all there was for towels, and, if one wished to sit down, books and dresses had to be put somewhere else. It had become scorching hot. I insisted in rigging up some sort of Screen under the skylight for decency’s sake. Squalor, wretchedness, into which no gleam of fun entered; I sympathized with royalty and was ‘not amused.’…”

Cecilia and May’s time in Paris and England had come to an end in August 1889 and the pair boarded the steamship Anchoria at the Scottish port of Greenock Harbour on the River Clyde. On the twenty-second of August, the pair set sail ploughing their way through rough seas and a blanket fog. The intrepid pair finally arrived back in Philadelphia at the beginning of September 1889 after almost nineteen months away from home. Once home, her family bombarded Cecilia with questions about her European adventure and her plans for the future. Cecilia was unequivocal about her future life. It would be dedicated to her art and from the sale of her paintings she would shore up the family finances. She was also equally definite that her future life and plans would not be hampered by relationships with possible suitors. The family accepted her views and her plans for the future and set about trying to help her.

Her uncle, William Biddle, found a new studio for her at 1710 Chestnut Street, and then helped her arrange it so that she could set herself up as a professional artist. She and her cousin Emma shared the studio. At the same time her family relieved her of all household duties. The sense of family loss was two-sided, for not only did her sister and aunts miss Cecilia, but she also missed her family despite the good times she experienced in Europe. Maybe it was the happiness of being back, once again, in the family fold that enticed her to complete many portraits of her sister’s family and other relatives. She also received many portraiture commissions from the Philadelphia “elite”. In the five years after her return home she completed over forty portraits.

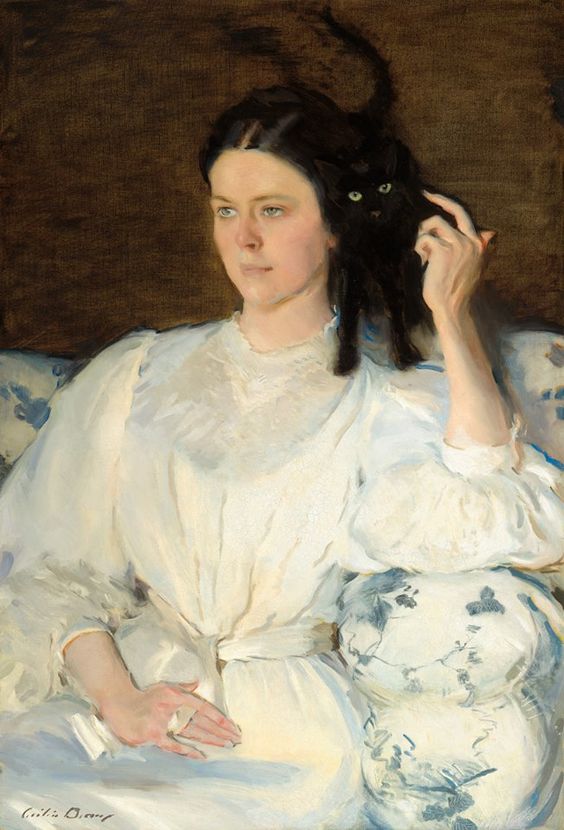

Probably her most famous family portrait was completed in 1894 and was entitled Sita and Sarita (Jeune Fille au Chat). It is a depiction of her cousin, Charles W. Leavitt’s wife Sarah (Allibone) Leavitt and the mysterious title of the painting comes from Beaux’s use of Spanish diminutives, Sarita for Sarah and Sita, meaning “little one,” for the cat. Sarah is dressed in white, with a small black cat perched precariously on her shoulder. The eyes of both the woman and the cat are green and almost lined up horizontally in the depiction. The combination of the whiteness of her dress and the palid complexion of her face are in direct contrast to the black furry animal standing on her shoulder. Both human and animal stare out enigmatically. Cecilia Beaux donated this painting to the Musée de Luxembourg and it is presently housed in the Musée d’Orsay. Twenty-seven years later she painted another version of the painting which is now housed in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, part of the Corcoran Collection.

Another of her well-known portraits, Dorothea and Francesca, was that of the two eldest daughters of Helena de Kay and Richard Watson Gilder. Richard Watson Gilder was a poet and editor of the periodicals Scribner’s Monthly and The Century Magazine, and his wife Helena, who was artistically trained at The Cooper Union in Manhattan, was a portrait, still-life, and flower painter, and also a writer. The Gilders, who were very good friends of Cecilia, were leading lights of an artistic literary and music circle in New York and they played a central role in the founding of the Society of American Artists in 1877. Cecilia recalled in her biography the setting for the painting which took place in the Gilder’s Four Brooks Farm in Tyringham, Massachussets:

“…The big and little sisters, Dorothea and Francesca, used to execute a dance of the simplest and all too circumscribed design, invented by themselves, and adorned by their unconscious beauty alone. This was the subject. I built a platform with my own hands, as the girls could not move easily on the bare earth. When it rained hard, in September, the orchard let its surplus water run down the hill and under the barn-sill, so that, as my corner was rather low, I put on rubber boots and splashed in and out of my puddle, four inches deep. October was difficult, for it grew bitterly cold. But valiant posing went on, though the scenic effect of the group was changed by wraps. Summer, indeed, was over, when on a dark autumnal night, in the freezing barn, the picture was packed by the light of one or two candles and a lantern…”

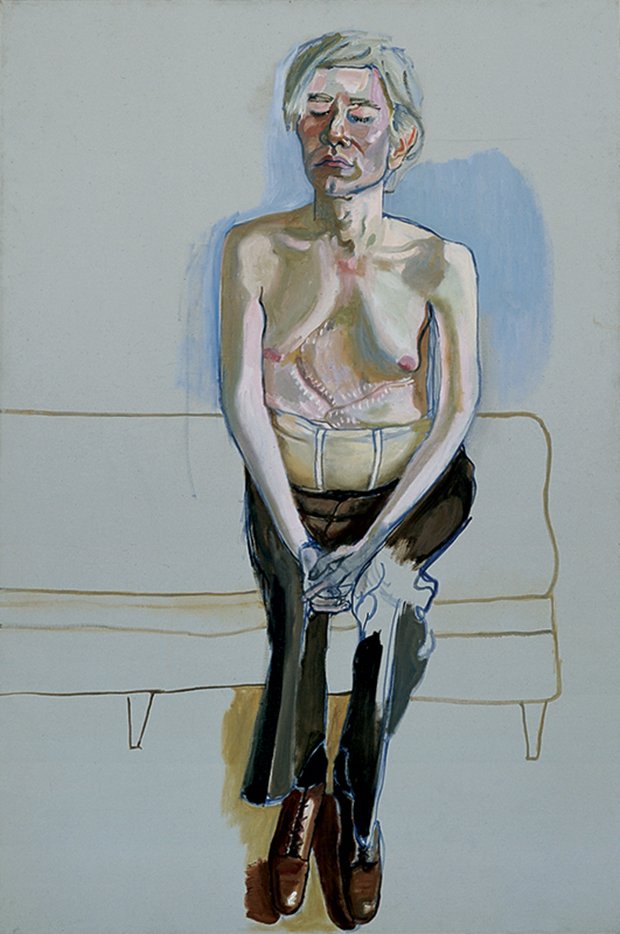

Cecilia Beaux’s cousin, Charles Wellford Leavitt, featured in another of her works. She completed the painting, Charles Welford Leavitt, the Artist’s Cousin in 1911. The sitter, who was forty at the time of the sitting, was a successful engineer and pioneer in the field of city planning. To acknowledge his profession Cecilia has added some of the tools of his trade on a table next to him. She has portrayed him with his arms crossed in front of him and his demeanour oozes a sense of importance and confidence.

In my final blog about the life of Cecilia Beaux I will look at her later years and the many portraits she did of the rich and famous.

…………………………………to be concluded.

Most of the information for the blogs featuring Cecilia Beaux came from two books:

Background with Figures, the autobiography of Cecilia Beaux

Family Portrait by Catherine Drinker Bowen

and the e-book:

Out of the Background: Cecilia Beaux and the Art of Portraiture by Tara Leigh Tappert.

Extracts from letters to and from Cecilia Beaux came from The Beaux Papers held at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art

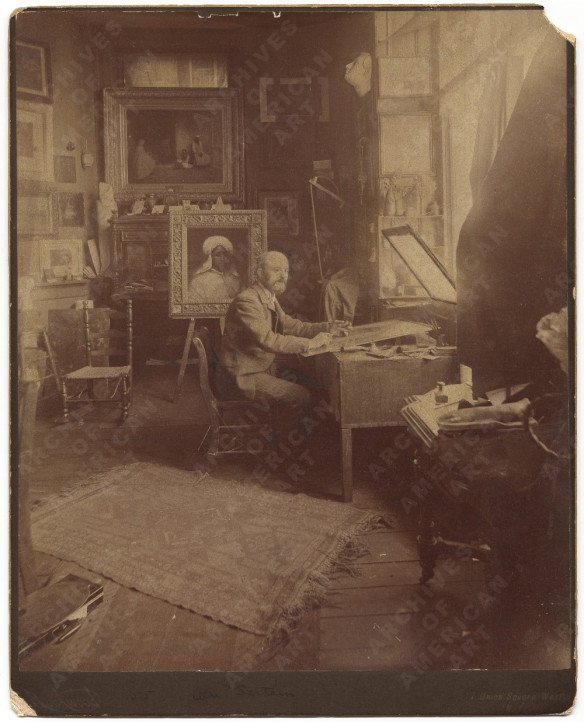

Photograph from Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts archive

Information also came from the blog, American Girls Art Club In Paris. . . and Beyond, featuring Cecilia Beaux was also very informative and is a great blog, well worth visiting on a regular basis.:

https://americangirlsartclubinparis.com/tag/catherine-ann-drinker/