Marie Laurencin, Paris (c.1912.)

Marie Laurençin’s paintings dating from around 1910 have a strong flavour of cubism. However, she once again stated that although the experiments of cubism fascinated her, she was adamant that she would never become a cubist painter because she was not capable of it.

Bateau-Lavoir c. 1910

Laurençin spent a lot of time at Picasso’s open studio at the Bateau-Lavoir, (Laundry Boat) building at 13 Rue Ravignan at Place Emile Goudeau in Montmartre in the 18th arrondissement of Paris. The building was so nicknamed as it was said to resemble the public clothes-washing boats moored on the Seine in the early years of the twentieth century. The ramshakle building was said to strain and groan when it was windy—just like the those laundry boats on the Seine. Here, Laurençin exhibited her work along with a group of artists known as the Bateau-Lavoir, which was the residence and meeting place for a group of outstanding artists and men of literature. It was here that she met Max Jacob, the French poet, painter, writer, and critic, and André Derain, the French artist, painter, sculptor and co-founder of Fauvism. She was also introduced to Gertrude Stein, the American novelist, poet, playwright, and art collector to whom she made her first sale in 1908.

Les jeunes filles (Jeune Femmes, The Young Girls) by Marie Laurençin (1911)

In 1911 Laurençin completed her painting entitled The Young Girls. Marie Laurencin showed The Young Women at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris in 1911, alongside works by other artists painting in a similar style. The exhibition, which gave rise to the term “cubism”, caused a scandal but was also the breakthrough for Cubist art. This work depicts four pale-skinned dark-eyed women with dark hair, independent of each other and yet overlapping. They are all wearing grey robes and stand against an abstracted pastoral backdrop. The female on the left is a violinist, playing music for the figure beside her, who dances. At the centre of the depiction we see a woman seated facing the dancer, but she turns her head to look back at us. On the right, another woman appears in motion, carrying a bowl of fruit under her right arm and reaching down with her left hand to stroke the nose of a doe. All the limbs of the women have a fluidity which mirrors the drape of their dresses. Their bodies are outlined with heavy black lines. Laurençin has experimented with this depiction and artistic style.

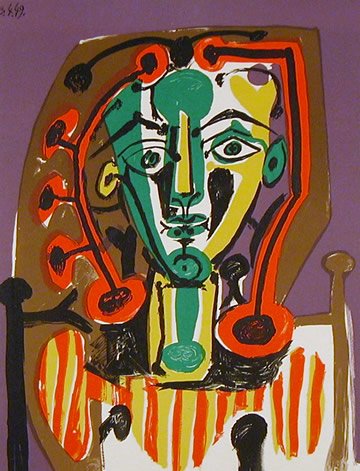

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon by Picasso (1907)

The posture of the four women with their flat, mask-like faces seems to have been influenced by her friend, Picasso’s 1907 painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. In a way the work can be considered as a suggestion that the four women represent a fertile sphere of feminine creativity. The presence of the doe is symbolic of femininity and naturalness that was a common theme in Laurencin’s work. Critics believe the painting alludes to the of lesbian self-fashioning and as a celebration of an independent female realm. The painting can be viewed at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm.

Portrait de jeune femme by Marie Laurencin

In 1913, Marie Laurençin’s mother died and this sad event coincided with her ending her relationship with Apollinaire, but this ending could have something to do with his reputation as a philanderer. However, she would remain close to Apollinaire until his death, aged 38, in 1918. Her split from Apollinaire freed Laurencin of his Cubist influence, but at the same time, isolating her. On June 24th 1914, in Paris, Marie married Baron Otto van Wätjen, a German Impressionist and Modern painter whom she had first met as fellow students at the Académie Humbert.

Marie Laurencin, Cecilia de Madrazo and the Dog, Coco by Marie Laurençin (1915)

In the Tate Britain, London, one can see the 1915 work by Laurençin entitled Marie Laurencin and Cecilia de Madrazo and the Dog, Coco. Cecilia was an art collector friend of Maria. Laurençin told a fellow artist that the painting was completed in 1915 while she and her husband were exiled in Madrid. The girl wearing the hat is Cecilia de Madrazo, a young Spaniard, and the other figure is Marie herself wearing a pink dress with her dog poking up between them. She had bought the dog from an English sailor at Malaga. Marie Laurencin was staying in Madrid with the Madrazos at the time. Marie has depicted herself with short hair which covers her ears and forehead. Although her skin is grey it is sharply in contrast with pink cheeks and lips and black eyes which are focused downwards. Cecilia is fascinated by the dog. She stares down at it and pushes a finger towards its very long snout. Cecilia’s skin is almost white, with pink lips and cheeks. She is wearing a grey dress and has a white hat, with a large blue bow, atop her dark hair. The backdrop, almost without detail, is grey and there is a pink curtain at the right edge of the painting; the colour scheme is very limited, with Laurencin utilising only grey, pink, blue and very small amounts of beige. This painting is representative of Laurencin’s work, which has been both appreciated and criticised for its deliberately feminine aesthetic. Marie’s palette concentrated on pastel colours. The two figures depicted add a sense of peace and charm and they own the conventional female virtues of loveliness, sophistication and meekness. Laurencin’s unapologetic embrace of visual pleasure and the way she developed an aesthetic that acclaimed female softness, elegance and sweetness was itself a radical position. Laurencin’s painting has depicted such qualities as part of a creative process in which a masculine form is utterly unnecessary, and in a way it is a presentation of a work in which both artist and subject are female.

The Fan by Marie Laurencin (1919)

In 1919 Laurencin completed her painting entitled The Fan and this, like the previous work, is part of the Tate Britain, London collection. The painting was purchased by Gustav Kahnweiler, an art dealer, as a gift for his wife, Elly. He and his wife amassed a modest art collection focused on Cubist paintings, sculptures, and works on paper. After the couple moved to England in the 1930s to escape Nazi persecution, Gustav and Elly loaned and gifted works from their collection to the Tate. It is believed that the woman in the oval frame is Laurencin herself but the identity of the other woman is unknown. The fan, which was a symbol of vanity, was one of Laurencin’s favourite accessories. The painting depicts a pink shelf that holds two images of women, one in a rectangular frame and the other in a round frame, against a pink and grey background. The portrait to the left, in the larger, rectangular frame, shows a woman and a dog in greyscale, accentuated by a pale blue ribbon, hat and curtains. Next to it is an oval frame at the centre of the painting depicting a woman reputed to be Marie Laurencin herself, though it is unclear if this is a portrait or indeed a mirror. The lower right corner of the painting is dominated by the folds of a fan, painted in grey and white, that is cut off at the canvas’s edge. Laurencin has cleverly depicted the fan in a position that could be seen as being held by someone who is staring at the two frames on the shelf. The two portraits in the frames on the shelf are positioned such that the figures appear to look out towards us but also towards the person holding the fan. There is an air of mystery about the depiction and the identities of the figures. Some believe that the woman in the rectangular frame is Nicole Groult, a dressmaker with whom Laurencin is likely to have had a romantic relationship.

Dona Tadea Arias de Enriquez by Goya (1793)

Once married to Otto van Wätjen, Laurencin automatically lost her French citizenship and so took up German citizenship. She and her husband moved to neutral Spain at the beginning of the First World War in order to avoid France’s anti-German sentiment. Here, Laurencin became involved with the Dada movement, editing the art and literary magazine 391, a Dada-affiliated arts and literary magazine created by Francis Picabia. She also spent time looking closely at the work of Francisco Goya, whose dignified, dark-eyed women captivated her.

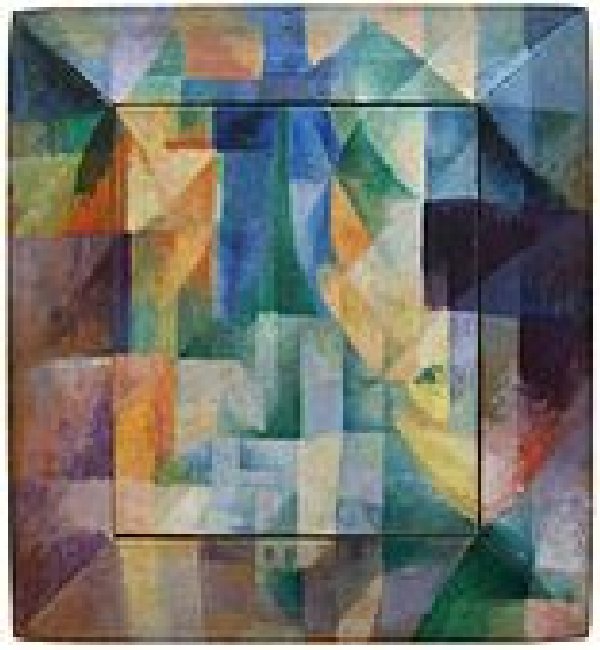

Simultaneous Windows on the City by Robert Delaunay (1912)

During this period in Spain she became great friends with Sonia Delaunay and Robert Delaunay, who had similarly left France to avoid the War. Robert was an artist of the School of Paris movement, who, with his wife Sonia Delaunay and others, co-founded the Orphism art movement, noted for its use of strong colours and geometric shapes.

……to be continued.