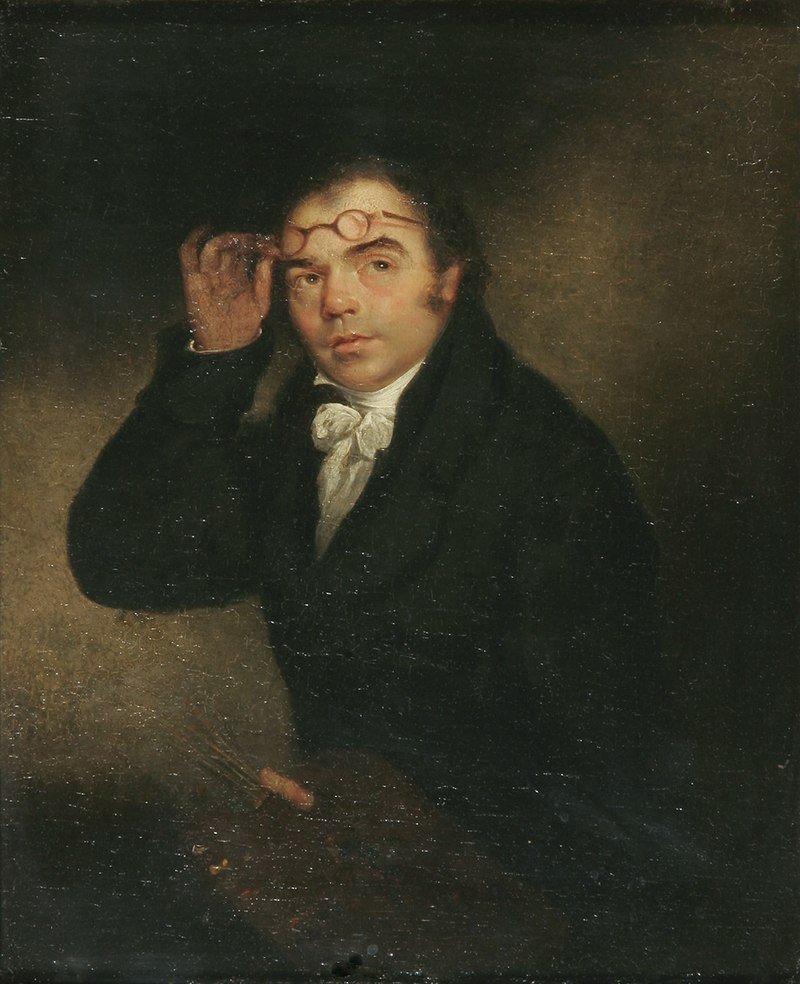

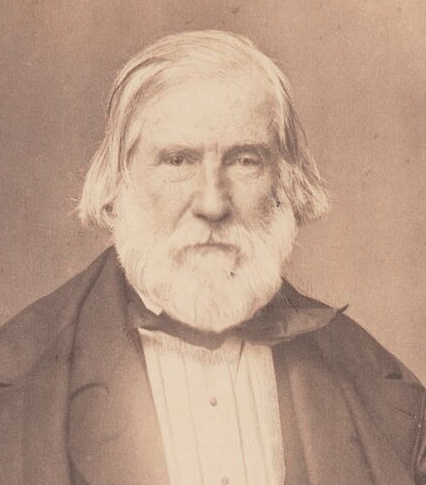

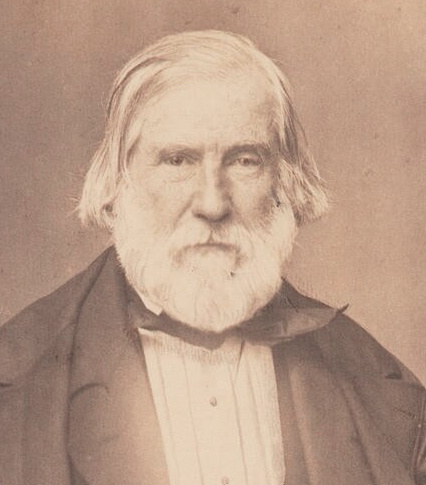

One of the founding members of the Norwich School of Painters was John Crome. Crome would become one of the three great landscape painters who came from East Anglia. The other two were Gainsborough and Constable. East Anglia was not known for its spectacular or romantic landscapes. Unlike North Wales or the Lake District, there was little to inspire a landscape painter and yet the quiet pastures of the Stour valley and the Dutch-like vistas of the Norfolk Broads attracted many nature lovers.

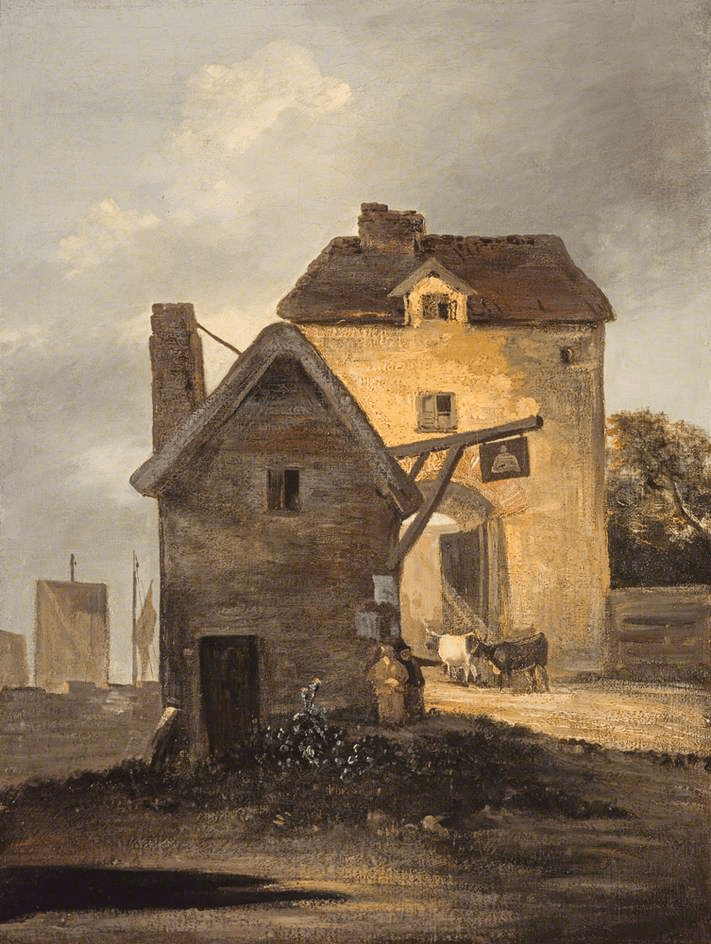

Crome was born on December 22nd, 1768 at the small Norwich ale-house called The King and the Miller and was baptised three days later on Christmas Day at St George’s Church Tombland, Norwich. Crome’s father, John, was an impoverished journeyman weaver. He was also either an alehouse keeper or lodged in an alehouse in a very disreputable part of Norwich, known as Castle Ditches. Crome’s mother was Elizabeth Weaver. Crome had very limited schooling and left at the age of twelve to become an errand boy to the distinguished Doctor Rigby. After a few years living with and serving the doctor, his employer arranged for him to be apprenticed to Mr Francis Whisler, a coach, house and sign painter, of 41 Bethel Street Norwich. Crome commenced his seven-year apprenticeship on August 1st, 1783. At first Crome’s job was to grind the coloured pigments and look after the brushes. He eventually was allowed to paint the signs, which meant that he had to learn the skill of making the depictions on the signs, stand out at a distance and this talent can be seen in many of his later paintings.

During his apprenticeship he struck up a friendship with Robert Ladbrooke, another young apprentice, one who was training to become a printer. The two young men, both of the same age, had one underlying desire – that of becoming painters. The two decided to work together to achieve that aim and rented out a garret and bought some art prints from the local Norwich print-seller, Smith and Jaggers, which they could spend time copying, and thus, honing their artistic skills. Crome and Ladbrooke would go on drawing trips into the fields sketching the scenery and then sell some of their works to the local print-seller. The print-seller was impressed with what the two young men could achieve and bought some of their drawings and it is very likely it is through Crome’s drawings that he gained the attention of Thomas Harvey, a local amateur artist and art collector. Thomas Harvey owned a number of paintings by old and modern Flemish and Dutch Masters, particularly Meindert Hobbema and Jacob van Ruisdael, which he had acquired through the good auspices of his Dutch father-in-law. He also had a collection of works by Gainsborough and Richard Wilson, which he allowed Crome to study and copy.

Through Thomas Harvey, Crome met William Beechy, a leading portrait artist who studied at the Royal Academy Schools in 1772, and is thought to have studied under Johan Zoffany. Beechy first exhibited at the Academy in 1776. In 1781, he moved to Norwich. Beechy could see that Crome was a very talented artist and became his mentor. Beechy, although living in Norwich, had a studio in London which Crome would visit regularly. Beechy wrote about the first time he met Crome:

“…Crome, when I first knew him, must have been about twenty years old, and was an awkward, uninformed country lad but extremely shrewd in all his remarks upon art, though he wanted words and terms to express his meaning. As often as he came to town he never failed to call upon me and to get what information I was able to give him upon the subject of that particular branch of art, which he made his study. His visits were very frequent and all his time was spent in my painting room when I was not particularly engaged. He improved so rapidly that he delighted and astonished me. He always dined and spent his evenings with me…”

On October 2nd 1792, Crome married Phoebe Berney in the medieval St Mary’s Coslany church in the centre of Norwich. The couple went on to have eight children, six sons and two daughters. Two of his sons, John Berney Crome and William Henry Crome became well-known landscape painters.

One of Crome’s rare forays out of the country came in October 1814 when he and two friends crossed the Channel on their way to Paris. Napoleon Bonaparte had just been defeated and hundreds of Englishmen flocked to Paris to view the art treasures held in the Louvre some of which were the spoils Napoleon had collected during his victorious campaigns. On October 10th, 1814, Crome wrote home to his wife informing her that he had arrived safely:

“…My Dear Wife, After one of the most pleasant journeys of one hundred and seventy miles over one of the most fertile countreys I ever saw we arrived in the capital of France. You may imagine how everything struck us with surprise; people of all nations going to and fro – Turks, Jews etc. I shall not enter into ye particulars in this my letter but suffice it to say we are all in good health and in good lodgings…”

Whilst in the French capital Crome set about pictorialy recording his visit and from the sketches he made, he completed a number of paintings on his return home. In 1815 he completed Boulevard des Italiens, Paris. It is a wonderful work, full of life and energy as we see people milling around the flea market. Crome exhibited the work in the Norwich Exhibition in 1815.

Another painting which came from his many sketches he made whilst in France, was one he sketched whilst on his journey back home. It was entitled Fishmarket on the Beach at Boulogne and Crome completed it in 1820.

Another painting which came from his many sketches he made whilst in France, was one he sketched whilst on his journey back home. It was entitled Fishmarket on the Beach at Boulogne and Crome completed it in 1820.

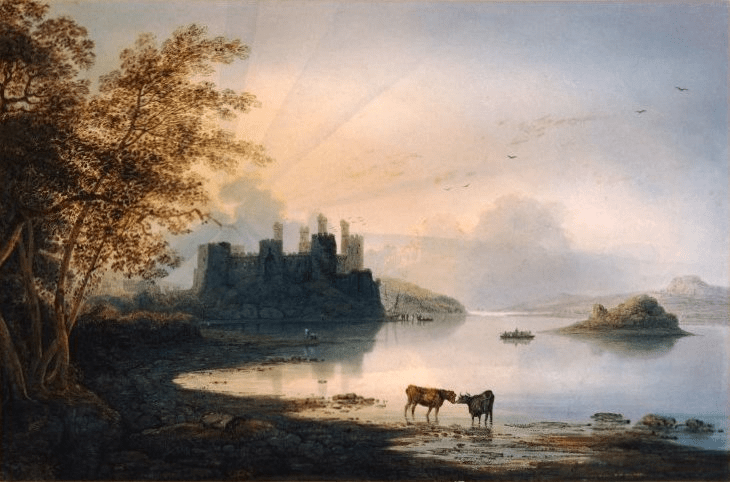

Unlike many other English artists, John Crome, besides his one trip to Paris, rarely ventured outside his beloved country and preferred to explore the countryside of East Anglia. He preferred the home life surrounded by his family. His main focus was on the English landscape and especially the natural scenery of the Norfolk area. He maintained that he only painted what he saw and never took poetic licence with his subjects. As he succinctly put it, I simply represented Nature as I saw her. Of Crome’s choice of depictions, one art critic wrote:

“…Crome painted ‘the bit of heath, the boat, and the slow water of the flattish land, trees most of all, the single tree in elaborate study, the group of trees, and how the growth of one affects that of another, and the characteristics of each…”

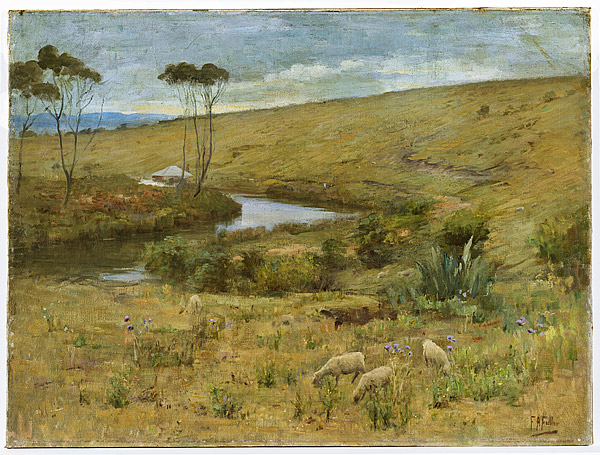

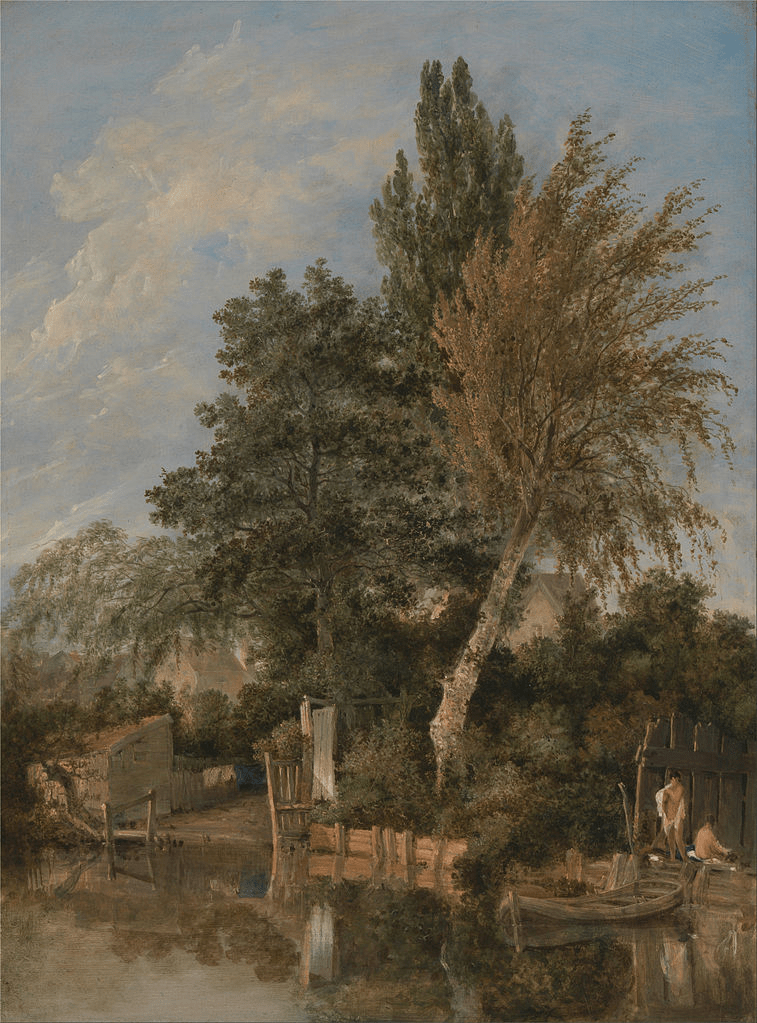

Crome was a gifted draughtsman and an authority when it came to depicting trees. He was one of the first artists of his generation to portray individual tree species in his works, rather than just painting simplified structures. His favoured tree was the English Oak tree. A fine example of this is his oil on canvas work entitled The Poringland Oak which he completed in 1820. Poringland is a village in the district of South Norfolk, England. It lies 5 miles south of Norwich city centre and the heathland around the village was one of Crome’s favourite haunts. The depiction centres on a large oak tree that would have been familiar to local residents. Look at the details of the tree Crome has given us. Look how he has masterfully depicted the clouds. This painting came many decades before the Impressionist works and yet it is a study of light, as the sun begins to set. The depiction we see before us is a perfect idyll. The sun is setting bathing the heath in a golden warmth. Bathers, wanting to relax, have taken to the lake after a hard day’s work.

Another of Crome’s paintings featuring the area he loved so much was completed around 1820 and was entitled Mousehold Heath, Norwich. Mousehold Heath was a well–known stretch of common land which lies five miles north of the city of Norwich. It is a unique area made up of heathland, woodland and recreational open space. Crome’s painting accentuates its vastness and lack of cultivation. In the foreground Crome has depicted clumps of wildflowers and, in the distance, we can just make out cattle grazing freely on the heath. The painting has the feel of a Dutch painting such as those by Aelbert Cuyp which Crome may have seen in the painting collection of Thomas Harvey. Although this painting was completed around 1820 it was probably a view of the Heath some five or ten years earlier as around 1814 a large quantity of land, including this area, was “enclosed”. Once enclosed, use of the land became restricted and available only to the owner, and it ceased to be common land for communal use. In both England and Wales, this process of allowing cultivation of open land was to boost the production of food.

Besides the money he received for his paintings his income was further increased by teaching art to the “great and good” and he often travelled around to various country homes in his profession as a drawing master. It was during these visits that he would once again have come across many paintings by the Dutch and Flemish Masters. Seeing such collections also gave him an interest in starting his own collection and soon he was fixated on attending sales at auction rooms and he soon built up his own collection of books, prints and drawings. He bought and bought and soon his home was cluttered by his purchases. One can only presume that his wife stepped in and told him that “enough was enough” for an advert appeared in the Norfolk Chronicle:

“…At Mr Noverre’s Rooms, Yarmouth on Wednesday the 23rd of September 1812 and two following days. A capital assemblage of Prints and Books of Prints; Etchings; Finished Drawings and Sketches by the best masters – Woollett, Strange, Fitler, Bartolozzi, Rembrandt, Waterloo etc. They are the genuine sole property of Mr Crome of Norwich – a great part of whose life has been spent collecting them. Descriptive catalogues, price 6d. each of the booksellers of Yarmouth, Norwich, Lynn, Ipswich and Bury…”

There was no mention of the name of the auctioneer and thus it is supposed that Crome himself ran the auction. Although Crome’s had lost his precious collection he was soon visiting sales rooms again, steadily building a new collection !

John Crome’s life came to an end, after a sudden illness, on April 22nd 1821. He was fifty-two years old. Crome’s thoughts were constantly directed towards the art he so passionately loved. It is believed that on the day of his death he spoke to his eldest son, twenty-seven year old John Berney Crome. He begged him never to forget the dignity of Art, saying:

“…John, my boy, paint but paint for fame, and if your subject is only a pigsty – dignify it…”

It is said that Crome’s last words on his death bed were a cry from the heart and a loving testament to his favourite landscape painter:

“…Oh, Hobbema ! my dear Hobbema, how I loved you…”

John Crome was buried in the medieval church of St George’s-at-Colegate, Norwich and according to The Norwich Mercury, the local newspaper, an immense concourse of people bore grateful testimony to the estimation in which his character was generally held.

John Crome was often referred to as “Old Crome” to differentiate him from his talented son the artist John Berney Crome who was referred to as “Young Crome”.

A good deal of information about the Norwich School of Painters came from a book published in 1920, entitled The Norwich school; John (“Old”) Crome, John Sell Cotman, George Vincent, James Stark, J. Berney Crome, John Thirtle, R. Ladbrooke, David Hodgson, M.E. & J.J. Cotman, etc. by Charles Geoffrey Holme. This book can be read on-line at:

https://archive.org/details/cu31924014891992/page/n3

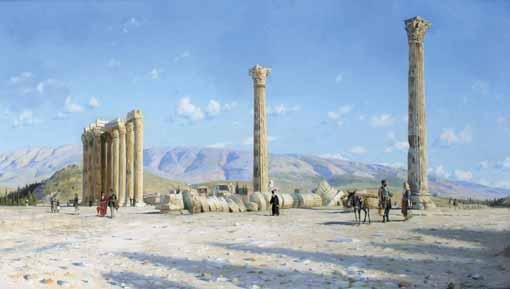

With his royal invitation to Greece, he also took the opportunity to depict the ancient sites. The above large-scale work (80 x 137cms) is one of his finest paintings of the last decade of the nineteenth century. It is thought that the two finely-dressed people depicted to the left in the mid-ground are King George I and his wife, Queen Olga of Greece. Further to the left are members of the famous Presidential Guard known as the Evzones. From Greece, Mønsted travelled to Egypt and Spain.

With his royal invitation to Greece, he also took the opportunity to depict the ancient sites. The above large-scale work (80 x 137cms) is one of his finest paintings of the last decade of the nineteenth century. It is thought that the two finely-dressed people depicted to the left in the mid-ground are King George I and his wife, Queen Olga of Greece. Further to the left are members of the famous Presidential Guard known as the Evzones. From Greece, Mønsted travelled to Egypt and Spain.