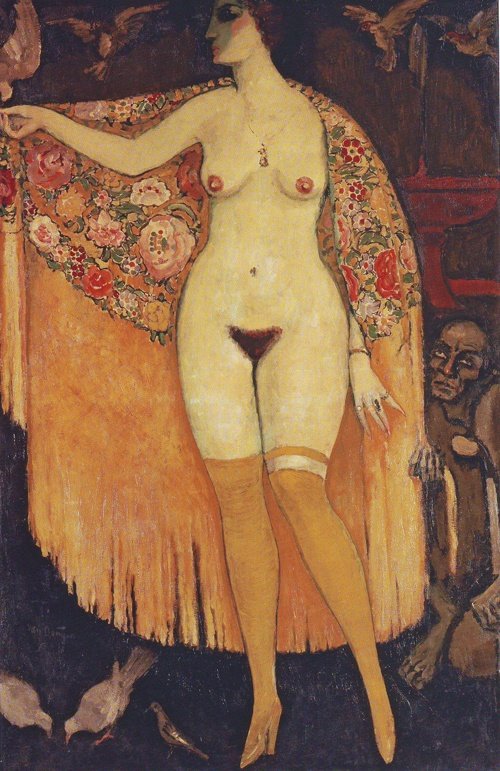

In my next few blogs I want to look at the life of a female who was both a great artist and artist’s model and whose name is synonymous with the artistic world of the late nineteenth/early twentieth century Montmartre. She was, and still is, loved by the feminist movement who applaud her guts and determination. She is Suzanne Valadon. I want to spend time and look at the artistic friends she made during her life and how they adored her. She was, to many artists, a model, a muse and, in some cases, a willing lover. To fully understand why her lifestyle was as it was, one must go back and examine her family roots and look at her early childhood which was , as is the case for nearly all of us, the sewing and the germination of the seed which would eventually blossom and shape our lives.

To examine her early life one needs to scrutinize the circumstances of her birth and for that it is necessary to look into the life of her family. Her mother was Madeleine Valadon who was born in the small rural village of Bessines, close to the town of Limoges. What we know of Madeleine comes from her own lips later in life and because she frequently changed the facts one needs to be careful as to what to believe. She maintained that as a teenager she had once been married to a man from Limoges named Courland and that he died in jail when she was just twenty-one years of age but by which time she had given birth to a number of his children. After his death Madeleine reverted back to her family name of Valadon and returned to her family home. As a young girl, she was taught to read and write by nuns who also taught her to stitch and sew. She then fortuitously managed to secure employment as a live-in seamstress to the well-to-do Guimbaud family who lived nearby. It was a position which she was pleased to accept and felt no grief for having to leave her children in their less than salubrious family home whilst she was living in comparative comfort close by. She soon established herself as the head of the servants in the Guimbaud household and, unlike them, even dined with the family. She remained in this employment for thirteen years but it came to an end when she once again became pregnant. According to her, the father of the child was a local miller who was killed in an accident at work. In later life she viewed the accident which killed him as divine retribution for making her pregnant!

Naturally the small Bessines community was shocked by the news of her pregnancy and lack of a husband to act as a father figure to her newborn. The Guimbaud family however treated her well and she remained in their house until her child, a daughter, was born. According to the official records, the child was baptised Marie-Clémentine Valadon on September 23rd 1865. It was not until she was nineteen years of age that Marie-Clémentine started calling herself Suzanne and this apparently was the suggestion of her friend, the artist, Henri Toulouse Lautrec. It is also interesting to note that despite that documented official registration of her birth Suzanne always maintained she was born in 1867.

Madeleine Valadon left Bessines with her baby in January 1866 and headed for Paris. She never looked back. She never saw or communicated with her family, her other children or her former employer, the Guimbaud family, ever again and one can only wonder why she wanted this complete break from her past.

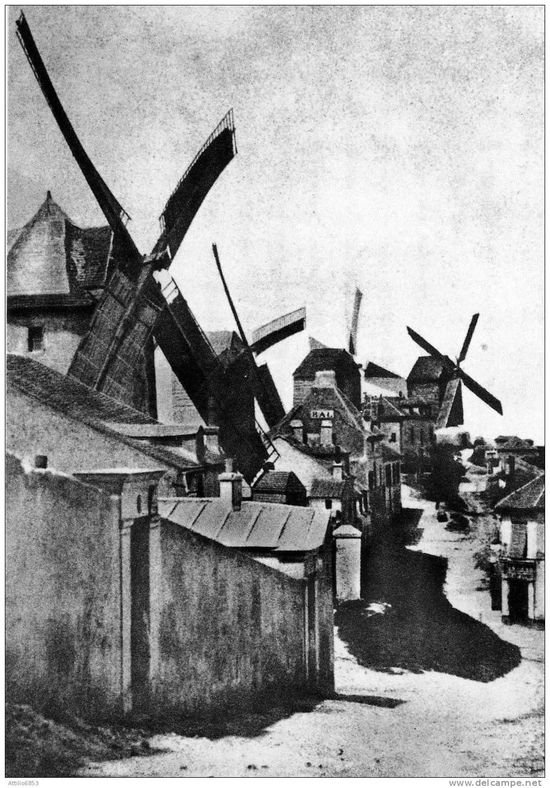

She arrived in Paris confidant that she would be able to earn a living as a seamstress. Madeleine Valadon was amazed at the sight that greeted her to the north of the capital city – a hill on top of which were a number of windmills, a vista which was similar to the rural views back home. The steep hill she viewed was the Mount of Martyrs, named after the execution of the first bishop of Paris, St Denis and his faithful lieutenants, St Rustique and St Éleuthère in the third century – Montmartre. Madeleine settled into lodgings at the base of the hill in the Boulevard de Rochechouart and then, with a glowing reference from the Guimbaud family, set off to procure employment as a seamstress. Her plans did not come to fruition as jobs were scarce and finally, in desperation, she had to settle for the menial job as a scrub-woman, cleaning floors whilst the wife of the concierge of her lodgings looked after Suzanne.

Madeleine, no doubt aware that for her daughter to succeed in life she had to be educated, and so arranged for a priest to teach her to read and write and then had her attend the convent run by the nuns of St Vincent de Paul as a day pupil for a continuance of her education and to be taught, as she was, to become a seamstress. However, once again her plans went awry with the start of the Franco-Prussian War which culminated in the siege of Paris by the Prussian army at the end of 1870 and the ousting of the French government, which retreated from Paris and based itself in Bordeaux. In May 1871, following the conclusion of the Franco-Prussian War and the lifting of the Prussian siege of Paris, the French government returned to Versailles on the outskirts of Paris ready once again to rule the capital. However many of the Parisians, who had suffered during the Paris siege, blamed their government for their misery and deprivation which they had to endure. They remembered with bitterness the days they had to scavenge for food eating dogs, cats and rats to survive. Out of this sense of bitterness and betrayal came the rise of the Communards. The Communards were a group of working class disaffected Parisians who did not want the French government to return to control Paris. They were very active around the area where Madeleine and Suzanne lived and their bloody determination that the defeated French government would not return to Paris from their bolt-hole at Versailles set up a clash which was in fact a mini civil war and which claimed the lives of more than twenty thousand Parisians.

Suzanne, during these times of turmoil, had still attended the St Vincent de Paul convent for her lessons and during the Paris siege had been fed by the nuns from their home-grown produce. However during the Paris Commune clashes between the government forces and the Communards the fighting had been so intense that the nuns barricaded themselves in the convent and closed it down to the day pupils and so Suzanne like many others lost their opportunity for learning and being fed. Suzanne, who was six years of age and like many children of her age, revelled in not having to go to school. Her mother, on the other hand, despaired and began to drink heavily. At the end of the Paris Commune struggle at the end of May 1871 and with it, the return to law and order under the French government, the St Vincent de Paul nuns felt it safe to re-open their convent to their day pupils and Suzanne, who had enjoyed the freedom from the discipline of school life and the boredom of lessons reluctantly had to return to the confines of the convent. She rebelled and was frequently absent preferring to play in the streets and on the hill of Montmartre with new friends both children and adults. She mixed with the lowest elements of society, the prostitutes, the beggars and the thieves and loved every minute of it. Later in life she recalled those times:

“…From that day the streets of Montmartre were home to me. It was only in the streets that there was excitement and love and ideas – what other children found around their dining room tables…”

Suzanne lived a feral existence. She was small in stature and had a fierce temper and would often succumb to uncontrollable rages and on the streets of Montmartre she was often referred to as “The Little Valadon Terror”. Her mother Madeleine became more morose and apathetic as the years passed. She lost total interest in life and frequently descended into an alcoholic haze. She rarely cleaned their lodgings and seldom did any laundry. She begrudged cooking and having to feed Suzanne and when they ate at meal times they would normally eat apart. Nothing Suzanne would do would lift her mother’s spirit. Despite this lack of maternal love for Suzanne the two lived together for almost sixty years. In later life Suzanne often depicted her mother in paintings. She would nearly always portray her as being old, wrinkled and toothless but showed her hard at work.

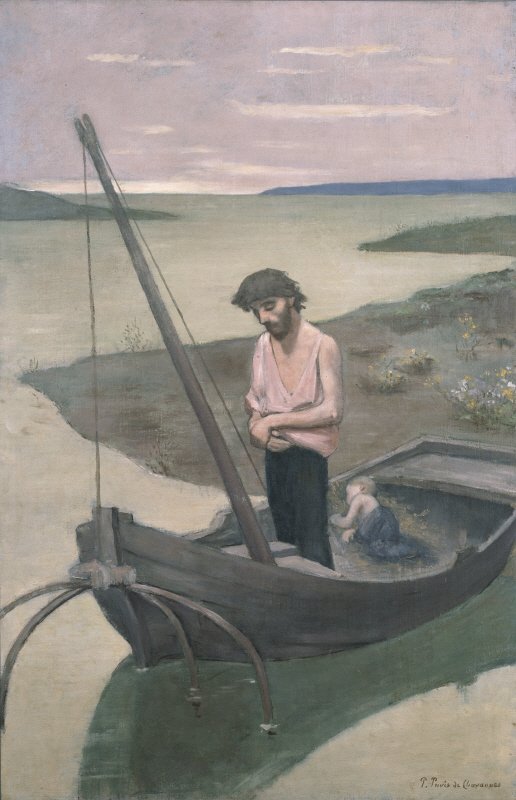

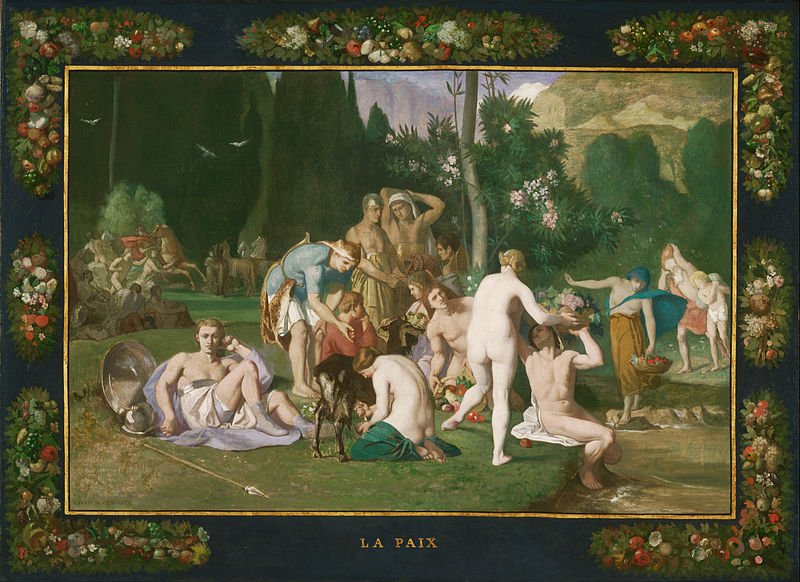

Montmartre since the beginning of the 19th century was the centre of artistic life and drew artists, musicians and writers to it like a magnet. Studio garrets shot up everywhere in which the artists would paint day in and day out and in the late evenings would look for some respite and so bars and music and dance halls, such as the notorious Moulin Rouge.

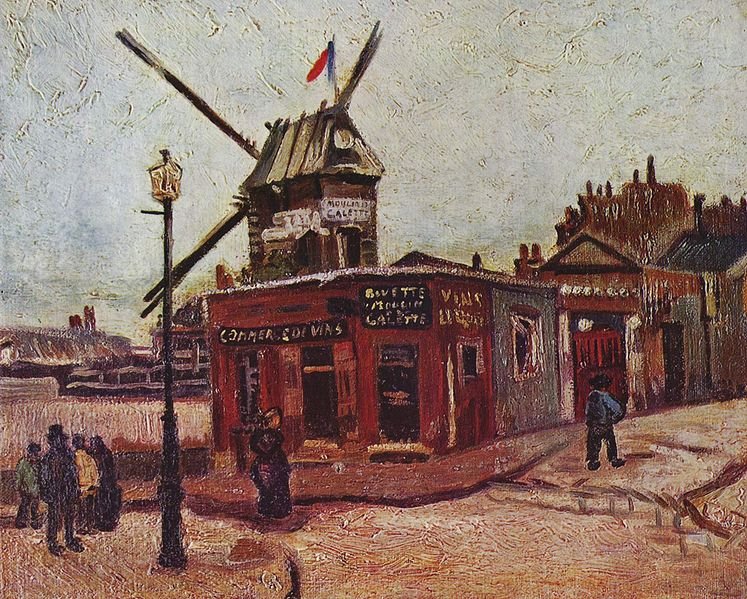

The Café de la Nouvelle-Athènes, was a meeting place for the up and coming artists of the time including the “new kids on the block”, the Impressionists and it was outside this establishment that Degas depicted the two drinking companions in his famous 1876 work L’Absinthe (See My Daily Art Display June 7th 2011). Another popular establishment was Le Chat Noir, which opened in November 1881 in Boulevard Rochechouart, the same street where Madeleine and Suzanne lived and was run by the entertainment impresario, Rodolphe Salis. The Divan Japonais, a café-concert (a combination of a concert hall and a pub) was a haunt of the French painter, Henri Toulouse-Lautrec. Probably one of the most popular was the Moulin de la Galette. This was originally a windmill, one of the thirty windmills on La Butte de Montmartre, which Madeleine saw as she arrived from Limoges. The windmill owners then added a goguette (a wine shop) which also sold galettes (flat round crusty pastries) and later incorporated a dance hall and restaurant. It was here that Suzanne Valadon reminisced that she had first set eyes on Degas whom she described as:

“…a small round-shouldered man, fragile and sad-eyed, in pepper-and-salt tweeds, his throat swathed in woollen scarves…”

In 1874, at the age of nine, Madeleine took Suzanne to an atelier de couture where she was apprenticed as a seamstress. Suzanne hated the life and made numerous attempts the workplace but unlike the nuns the workhouse owner would beat her when she was dragged back to the factory by her mother. She stayed there for three years but eventually left and took jobs as a waitress in a café, a push-cart vendor of vegetables and working with horses at a livery stable. It was this last job in which one of her jobs was to walk the horses around the streets. People would stop on the street and watch this small young girl with her large horses. Suzanne, ever the entertainer, was not content with just walking the horses but began to perform acrobatic tricks upon the horses to gain more notice and a modicum of applause. In later years, she reckoned that a circus owner witnessed one of her “performances” and offered her a job. She loved this new colourful and exciting life. Although her role at the circus/carnival was a horse riding act, one day she was asked to stand in for a trapeze artist who had been taken ill. She had done some trapeze work and so agreed. Unfortunately the performance went badly and she fell, injuring her back and her circus life came to an end.

…………………… to be continued.

Having been chastised the other day for not acknowledging some of my sources I thought I had better behave myself today and tell you that most of my information came from a book I read (and I am still reading it) on the life of Suzanne Valadon entitled The Valadon Drama, The Life of Suzanne Valadon, written by John Storm in 1923.

Other sites I visited to find some pictures were:

http://lapouyette-unddiedingedeslebens.blogspot.co.uk/

http://youngbohemia.blogspot.co.uk/2012/01/suzanne-valadon_8445.html

The Blog: It’s about time