Amélie Beaury-Saurel

Amélie Beaury a French painter, was actually born in Barcelona on December 17th 1848. Her family had previously lived in Spain and Corsica before moving to the Catalan city in 1845. Her parents, Camille Georges Beaury and Irma Catalina Saurel owned a large carpet and tapestry factory with more than twenty looms, which they called Saurell, Beaury y Compañía. Amélie was their middle child. She had an elder sister, Irmeta, also an artist, and a younger sibling, Dolores. Amélie later added “Saurel” to her name in recognition of her mother’s family who could trace their lineage to the Byzantine emperors of the 11th century.

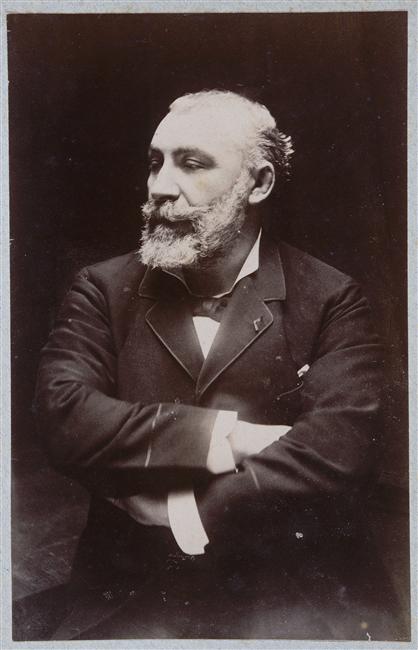

Portrait of the artist Jean-Paul Laurens by Amélie Beaury-Saurel (1919)

The happy family life was shattered in the late 1850s when Amélie’s father died and her mother decided to relocate with her three daughters to Paris. Amélie recalled in an interview that she and her family lived in the French capital when she was ten years old and that her widowed mother, with little money, had to endure financial hardships. Her mother instilled a love of art in her children and she would take them to the Louvre Museum to see the works of the Masters and encourage them to copy the works of the these great artists.

Portrait of Léonce Bénédite, curator of the Musée du Luxembourg, by Amélie Beaury Saurel (1923)

Due to this family impoverishment, Amélie’s mother decided that her daughters should help with the financial burden and set about having them train as porcelain painting, a socially acceptable way of earning a living and eventually becoming financially independent. Amélie set to work as a painter of porcelainware but later said she considered what she was doing as commercial painting which in many ways damped down her creativity. Her mother was very supportive of Amélie’s love of painting and, in 1874, initially paid for her nineteen-year-old daughter to study at the prestigious Académie Julian. One of her first tutors was Pauline Coeffier, a French oil painter and pastelist, who specialized in the art of portraiture. Later many of the leading artists of the day would advise and tutor her, such as Tony Robert-Fleury, William Bouguereau, Jules Lefebvre, Benjamin-Constant, Jean-Paul Laurens and Pierre Auguste Cot.

Rodolphe Julian

The Académie Julian was founded in 1868 by Rodolphe Julian. It was a private art school for painting and sculpture. Paris was looked upon as the capital of the art world, and the centre of modern art. This was one reason many young aspiring painters came to the French capital to discover all the latest trends in painting, like Impressionism and Post Impressionism, decorative art of various types, new forms of representational art such as expressionism, lithography and much more. Also with having a reputation as a forward-thinking art college the Académie Julian profited from the reputation of Paris.

Chez Duval by Rodolphe Julian

Another reason for the popularity of Académie Julian was that it was the only art school in Paris to accept foreign students, many of whom struggled to pass the difficult French language exam, which was conditional on their acceptance into the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Ambitious female painters were also barred from attending the official Ecole des Beaux-Arts until 1897 and even then, it was not considered suitable for women to study life drawing. In contrast, Académie Julian was happy to offer them a full programme of education and training to women in fine art. They were offered the same classes as men, including the drawing of nude models. In fact, the Académie was one of the few schools to admit women to life-drawing classes. In fact, one of its four new branches was actually exclusively designed for female art students.

The Académie Julian was also regarded as a stepping stone to the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts by getting them prepared for the entrance exams and at the same time offered independent alternative education and training in arts. Aspiring artists, both men and women, were welcome at the Académie Julian. Men and women were trained separately, and women participated in the same studies as men, including drawing and painting of nude models. The Académie Julian had no entrance requirements, was open from 8 a.m. until nightfall, and very soon became the most popular establishment of its type. Rodolphe Julian opened several branches throughout Paris, one of them especially for female artists, and by the 1880s the student population at these establishments reached six hundred.

Female Students at the Académie Julian in Paris, c. 1885

To ensure the success of the Académie, Rodolphe gathered together well-known and esteemed artists, such as Adolphe William Bouguereau, Jean-Paul Laurens, Tony Robert-Fleury, Jules Lefebvre and other foremost painters of that time trained in Academic art, to become tutors or visiting professors. Académie Julian became recognised as a leading art establishment and its students were allowed to compete for the Prix de Rome, a prize awarded to promising young artists, and also show their work in the major Salons or art exhibitions.

So, who was Rudolphe Julian?

Rodolphe Julian was born in Lapalud, a commune in the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur region in southeastern France on June 13th 1839. He worked as an employee in a bookstore in Marseille but later moved to Paris, where he became a student of Léon Cogniet and Alexandre Cabanel, professor at the École des Beaux-Arts, albeit he never officially enrolled there. Rodolphe was well aware of the struggles of artists who looked for artistic training once they had arrived in Paris and so, in 1863 he opened his own art school, Académie Julian.

Portrait of a Woman by Amélie Beaury-Saurel

Living in Paris, Amélie was determined to increase her knowledge of art and the Académie Julian offered her the best way of achieving that goal and eventually becoming a professional portrait artist. However this course of action had to be funded so she approached Rodolphe Julian and proposed that in return to her helping out with the administrative and financial duties of the Académie, he would allow her to attend his classes free of charge. He agreed. Rodolphe Julian had opened a women’s workshop in 1873 and in 1895 he put Amélie in charge of it. As well as organising the workshop she had begun a very lucrative career as a portrait artist and received many commissions.

Académie by Amélie Beaury-Saurel (1890)

In 1890, Amelie completed one of her greatest paintings entitled Académie. The title for the work refers to the art academy which at the time prohibited female painters from joining its ranks. Her depiction conveys the compelling message to the viewer that she was not going to allow herself to be browbeaten by the male-dominated artistic establishment and she would not conform to their dictates. The model in the painting exudes strength and determination as she stands grasping stalks of bamboo and stares out at us, challenging us. It can be no coincidence that Amélie has depicted her model naked and this nude pose empathises the strong and defiant attitude women embraced as artists.

Deux vaincues (Two Defeated Women) by Amélie Beaury-Saurel (1892)

Two years later in 1892 Amelie produced another defiant depiction entitled Deux vaincues (Two Defeated Women). It is looked upon as a rallying call to all female painters to be fearless as they travel through the unwelcoming and unforgiving world of art education and artistic professionalism and the many obstacles they had to overcome. It was a plea to female artists to not allow themselves to be defeated in the face of the obstacles they would encounter. The sketch depicts two women, both naked, chained to a wall. Both face similar hardships but they have fared differently. The one with her back to us is slumped forward in a defeated pose, while the other, in contrast, stands boldly upright, unrepentant and stares out defiantly. The painting is a challenge to all women as to whether they give in or fight on. The work was exhibited at that year’s Salon.

Portrait de Séverine by Amélie Beaury-Saurel (1893)

In 1893 Amelie completed a portrait of Caroline Rémy de Guebhard. She was a French journalist who held strong non-conformist views which labelled her as an anarchist, socialist, and communist. She also was a great believer in feminist’s rights and opinions and this no doubt drew Amelie to paint the portrait. Caroline Rémy de Guebhard would use the pen name Séverine, derived from the Latin severus which means “rigorous” or “brave”, for many of her newspaper articles. When we look at the portrait, our eyes are immediately drawn to the vivid red flower on the sash of her dress. The flower symbolizes Séverine’s leftist political views. Look at her facial expression. It is one that exudes strength, determination and tells you that this lady will not be moved. Amelie’s ability as a great portraitist is borne out in this beautiful work.

Séverine by Renoir (c.1885)

A portrait of Caroline Rémy de Guebhard was also complted around 1885 by Renoir. It is in the permanent collection of the National Gallery of Washington.

Dans le bleu by Amélie Beaury-Saurel (1894)

One of my favourite works by Amelie is her 1894 painting entitled Dans le bleu. It is a pastel on canvas which depicts a young woman waking up in the morning and indulging in the gratification of smoking that first cigarette. However that is not the point of the depiction. It is all about feminist assertions. In this painting, we see a woman depicted in profile, boldly treating herself to the pleasures of escapism. It is a depiction of defiance as women at this time were not seen smoking, especially not in public. It was a habit that was counter to the feminine conceptions of the time. We should remember that Amélie Beaury-Saurel had dedicated a large part of her work to the female model and had always maintained the feminist cause. She supported the right to arts education and artist status for women. In 1894 when she was working on this painting her reputation in Paris as an artist was at its highest point and her paintings were exhibited all over the French capital.

The background of the work is very dark, predominantly blue and this allows the figure stand out in the work. It is hard to know whether the scene takes place in a private dwelling such as a kitchen or a living room or whether the setting was in a public place, such as a café. The woman in the depiction sits smoking a cigarette, chin in hand. She appears to be daydreaming. She seems preoccupied as she watches the blue smoke unfurl from her lips, drifting upward. What is she thinking about? Would she, like the smoke, like to drift away? Some have suggested this might be a Beaury-Saurel self-portrait, as the model resembles the artist. The depiction is simple and realistic and in no way staged. Amelie’s depiction is all about everyday reality and is without any hint of idealization which would have weakened the work and it is this simplicity that has added to the beauty of the depiction and has expressed the woman’s femininity.

Our Girl Scouts by Amelie Beaury-Saurel

In this painting by Amelie, the seven women are represented in a compact group, around a table with a pile of books. On the left, holding his handlebars in his hand gloved, the Belgian cycling champion, Hélène Dutrieu; next to her, holding a paintbrush, the publisher Anna-Catherine Strebinger (Madame Henri Rochefort) who was also a student at the Académie Julian; then the collector Marguerite Roussel looks at the viewer; in the center, in professional attire and pointing to an article in a code, the lawyer Suzanne Grinberg, an eminent member of the French Union for the women’s suffrage, created in 1909; leaning on her, in the outfit that she had adopted to travel safely to the Middle East, archaeologist and explorer Jane Magre-Dieulafoy. Then comes the novelist and journalist Lucie Delarue-Mardrus and aviator Elise Deroche, First woman to obtain a pilot’s license.

In 1895, Amélie Beaury-Saurel, married Rodolphe Julian and he put her in charge of the women’s workshops which he had started in 1873. Amélie managed the expenses for the women’s studio, served as an intermediary between instructors and students, and ran the women’s group but also continued her career as a portraitist. She earned a medal for her submissions to the 1885 Paris Salon and the bronze medal at the 1889 Exposition Universelle.

Chateau Julian, Lapalud

Rodolphe Julian died on February 2nd 1907, aged 67, and two months later on April 10th, Amelie’s mother died. Following the death of Julian, Amelie took on the role of director of the Académie Julian. This was a mammoth task and so she received help from her nephews Gibert and Jacques Dupuis, the children of her sister Dolores. Rodolphe Julian had bought a large house in the village of Lapalud, where he was born and on his death they were bequeathed to his nephews. Amelie bought this large property from her nephews and transformed it to accommodate her family. It was called the “Mas” Julian.

Amélie Beaury-Saurel

During her last years, Amélie continued to paint but also fought for women’s rights and supported women artists and their fight against male-dominated art circles. She participated in solidarity exhibitions for the benefit of institutions such as the Société des Artistes Français, the Société Nationale des Beaux- Arts or the Fraternité des Artistes. Such commitment to the promotion of art and her endless creative activity were recognized in 1923, a year before her death, through her appointment as Chevalier de la Légiond’honneur.

Amélie Beaury Saurel died on May 30th 1924 aged 75 at he Paris home which she had once shared with her late mother and sisters.

Information for this blog came from the ususal search engines plus: