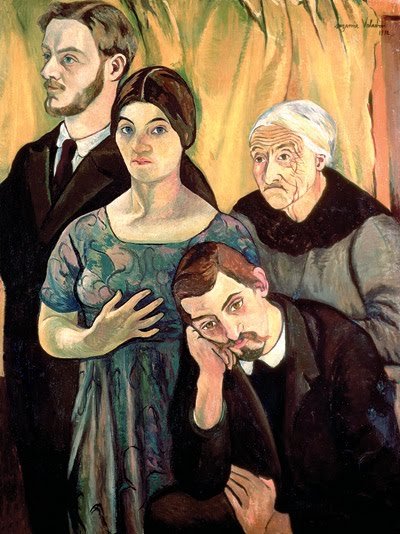

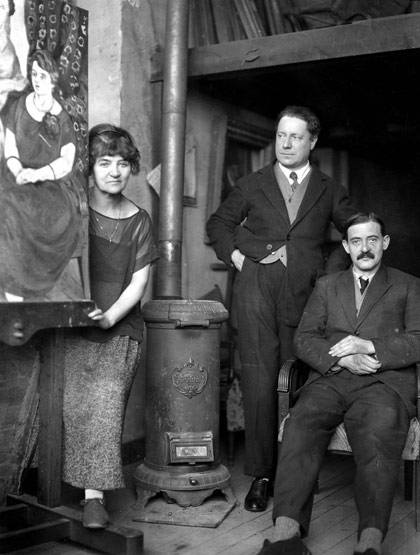

With their newly found wealth the acrimonious arguments ceased, long-standing bills were paid and new clothes were bought for Suzanne, her husband and her son. There was also a change in the fortunes of the trio for before they were all artists and all exhibited their works but now the Bernheim Jeune gallery just wanted paintings done by Suzanne and Maurice. Utter was now reduced to the role as their manager. He was the one who negotiated deals and organised exhibitions at home and in Europe. The new wealth brought happiness to their friends and neighbours as Suzanne was a generous soul. It was said that tiny street urchins would along the narrow streets of Montmartre clutching onto 100 franc notes which Suzanne had thrown to them from her top floor window in rue Cortot. Suzanne did not forget her mother in this exciting time and arranged to have a splendid granite tomb placed above her grave. She must have been thinking of the future for she the tomb inscribed in gold letters:

Valadon – Utter – Utrillo

Suzanne also remembered those idyllic months she spent with André in Belleville when he was recuperating and so she decided that she and André should return there for a visit. Sadly, as we all know, it is foolish to try and re-live old memories and their return was not as idyllic as she had imagined it would be as the couple lapsed into numerous arguments.

The one thing which did lift their spirits was an impulse buy on the day they were to return to Paris. They bought themselves a chateau which lay close to the River Saône, just 25 kilometres north of Lyon. They bought Le Chateau de St Bernard from the owner Antoine Goujot. The purchase lifted their spirits and they immediately sent out invites to all their friends back in Paris along with money to pay for their travel. Money was no object when it came to supplying food and drink to the chateau parties.

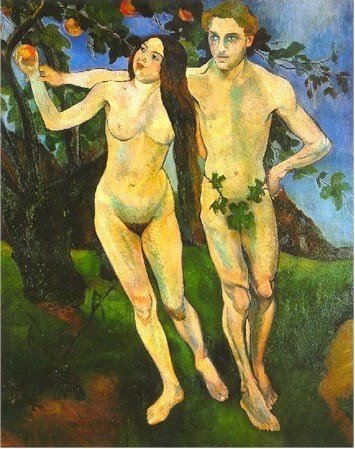

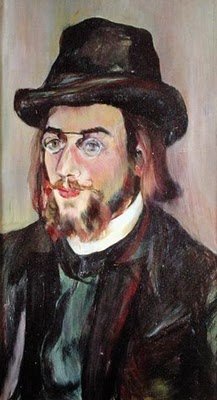

Finally André and Suzanne had to return to Paris and once again relations between the couple began to deteriorate. Their marriage was under extreme pressure and during their vociferous arguments André Utter struggled to remember the good days they had shared together when Suzanne was the one true love of his life. In those days he was mesmerized by both her outer and inner beauty and could not understand what had changed. The problem with Suzanne, although he could not see it, probably emanated from her mental and physical failure to grow old gracefully coupled with the effect her son’s mental issue were having on her. Maurice’s behaviour was also affecting Utter but he was less sympathetic as he himself had been an alcoholic and had weaned himself off drink and therefore he could not accept Maurice’s behaviour. Sadly Utter was overlooking Maurice’s mental issues which had little to do with drink. For Suzanne and André there were still times of unfettered sexual activity but these bouts became less frequent. The new wealth of the couple could not compensate for their troubles and could not fix them.

André Utter began to have love affairs and Suzanne was aware of his infidelity and strove to stop them but probably knew the situation was beyond redemption. She believed the reason for her husband’s infidelity was her fading looks whereas in reality it was probably due to her fragile mental state that had killed their relationship. Utter’s amorous trysts did not make him happy for very long as the women, aware of his wealth, were ever demanding. Soon he could not differentiate between their love for him and their love for his money. When one of his affairs ended disastrously, as they all did, he would return to Suzanne and beg her forgiveness. The locals were well aware of the situation between Suzanne and André and Suzanne being aware of this, ensured that everybody should be aware of her selfless magnanimity in forgiving her errant husband. As his sensual liaisons were not giving him the pleasure any more he turned back to drink as being drunk allowed him to escape reality and distance himself from his many lovers and the acerbic tongue of his wife. He would constantly bemoan his lot in life. Nobody loved him or his paintings any more. During his drunken outbursts he would become vile and malicious and Suzanne suddenly saw a different André. This was not the man she fell so deeply in love with back in 1908.

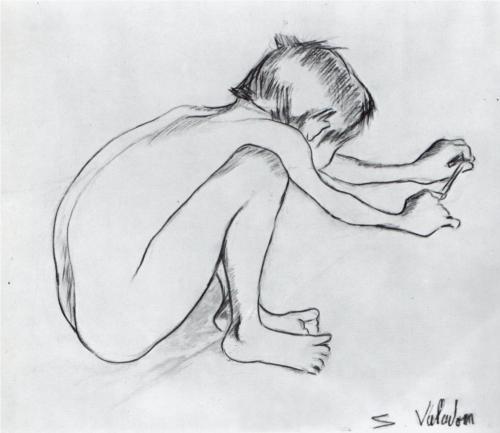

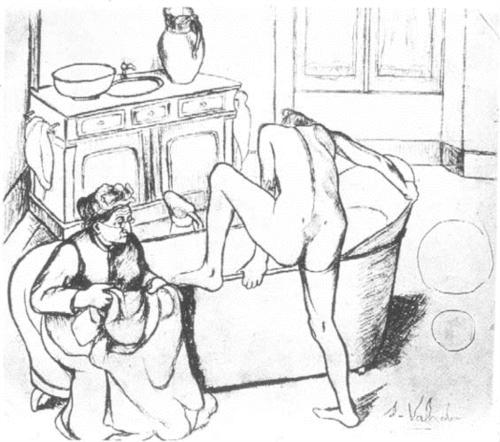

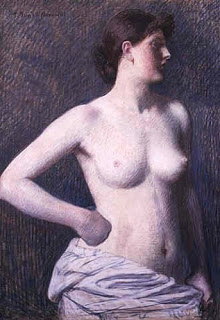

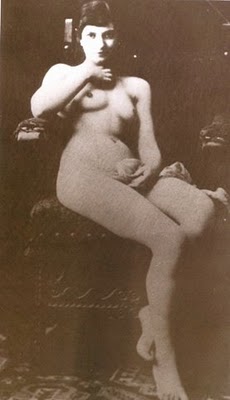

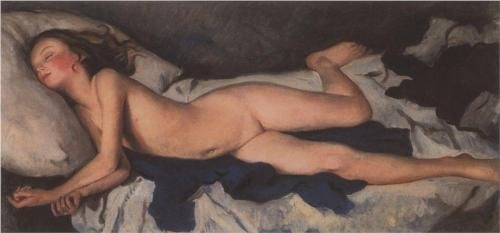

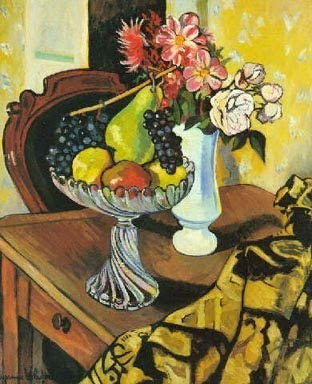

Suzanne tried to console herself by throwing herself back into her art which was still commanding a high price and the fact that her son’s works realised four or five times more that hers did not bother her; in fact she was proud of Maurice’s achievements. The subjects in her paintings changed. Gone were the nude studies to be replaced by still life depictions often featuring flowers which were painted in somewhat crude colours which she always liked using. She still went back alone to her chateau and host luncheons and dinner parties. Her extravagant lifestyle carried on. She would feed her dogs with only the best faux-filets and her cats feasted on caviar. People looked her as being a foolish old woman but she continued undaunted.

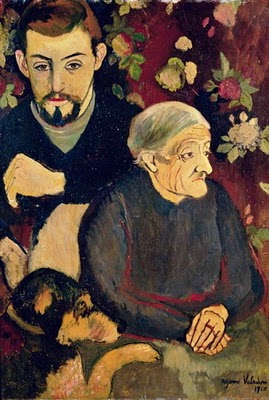

In 1924 Maurice voluntarily placed himself in a Paris sanatorium which was close by at Ivry. Maurice was still unable to accept that he had mental issues and put down his problems solely to his alcohol addiction. Suzanne was heartbroken that at the time of her son’s greatest artistic triumphs he was hell-bent on destroying himself. It could be that for the first time in her life she realised that the symptoms Maurice displayed as a very young child was the onset of his mental issues and could not forgive herself for not doing more then to try and cure what was ailing her son. Once Maurice left the sanatorium Suzanne took him off to the chateau and employed a male nurse to look after him. She tended to all his needs. She fed him. She dressed him and would go for long walks with him and at night she would sit in a chair next to his be until he fell asleep. André made a number of visits to the chateau but the romance and the love he had for the place had gone and the tantrums and behaviour of Maurice now simply annoyed him. Later he reflected on this saying:

“…This Eden was transformed into a real hell. I thought we had bought the place for peace. But Maurice was able to scream and shout about to his heart’s content. Suzanne replied in kind. And only the walls and the fish in the Saône listened to them…”

Officials at the Bernheim Jeuene gallery were beginning to worry about Suzanne’s profligacy and so as to protect the interests of their co-client, Maurice Utrillo, purchased a house for him in the Avenue Junot and put it in his name. It was a modern building with a studio and a small garden which Suzanne enjoyed tending. Gardening and flowers were the one and only thing Suzanne loved about life. Utter remained in their house at No. 12 rue Cortot as it still had memories for him of the beautiful woman he had once loved and the pictures he had once painted. Years later, after Suzanne had died, Utter wrote to a friend:

“…Always I dream of the rue Cortot and the beloved Suzanne. When we first moved there, how beautiful everything was – except for the gossips! And I knew then that it was the place I should always keep in my heart. Every man has a home. He is lost if he does not treasure it…”

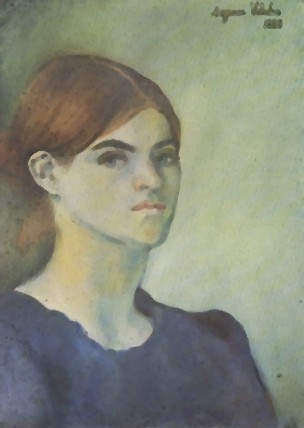

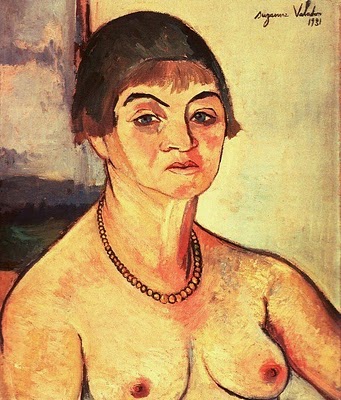

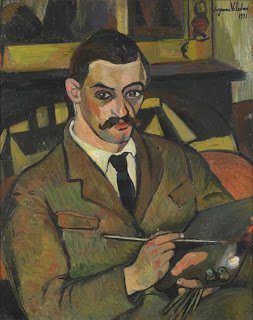

Suzanne’s art was still appreciated and in 1929 she was invited to show in the Exhibition of Contemporary Art – Women and Flowers and in the same year she exhibited work in the Painters, Self-Portraits exhibition. It was at this exhibition that she showed her extraordinary nude self-portrait which featured her as an aging woman gazing into a mirror. In 1932 Suzanne, Maurice and André had a joint exhibition of their work at Gallerie Moos in Geneva and they were all delighted with sales figures. That year Suzanne had a one woman exhibition of her paintings, drawings and etchings at the Galleries Georges Petit in Paris. It was an outstanding success. One of the visitors to the exhibition was Suzanne’s friend from her chateau days, the then Mayor of Lyons Édouard Marie Herriot who also served three times as Prime Minister and for many years as President of the Chamber of Deputies. Of the exhibition he wrote:

“…Alive as Springtime itself and, like Spring, clear and ordered without interpretation, Suzanne Valadon pursues her magnificent and silent work of painting……. I think of the words of Théopile Gautier ‘Summer is a colourist, winter a draftsman’. To us who admire and love her art, Suzanne Valadon is springtime – a creature in whose sharp, incisive forms we find fountains of life, the spontaneity of renewed day-to-day living. And those matters of the nineteenth century whose names we revere, I marvel that so scrupulous a respect for truth of form is able to achieve such a fete of colour and movement…”

Suzanne also had another troubling matter to deal with. What was to become of Maurice when she died? Her answer to that was that he should marry. Suzanne did not want to lose “control” of her son but believed a kind and dedicated woman would be the ideal wife for her troubled son. One candidate Suzanne had in mind was André Utter’s sister Gabrielle. Gabrielle, now in her thirties, had like André come from a humble background. She was a very caring person, deeply religious and not at all unattractive. In some ways she pitied Maurice which was a kind of love but in a maternal or sisterly sense. She and Maurice would talk together for hours and did all things close friends would do but this was not a physical relationship. After four years of this “courtship”, Suzanne, tired of waiting, forced the issue of marriage with Maurice but he was horrified with the suggestion and replied vitriolic ally:

“…I’ve had enough tragedy in my family with one of that family…”

An official delegation of the government descended on Chateau de Bernard to formally present Maurice with the Cross of the Legion de Honor in 1927 for his services to Art, for by this time he was an internationally acclaimed artist. I have to admit that whilst researching this blog I read that the award was in 1928 and other sources said 1929!

In January 1935, now in her sixty-ninth year, Suzanne was taken seriously ill and rushed to the American Hospital at Neuilly where she was diagnosed with uremic poisoning. One of her visitors was Lucie Valore, who had reverted to her maiden name and who many years ago was Lucie Pauwels, who visited Suzanne with her banker husband to buy some of her paintings. Her husband had died two years earlier. What happened and what was said at Suzanne’s bedside depends on the version of the story you wish to believe. According to Suzanne, Lucie had simply come to visit her and during the visit had said that as Suzanne was unable to look after Maurice she would take on the role as carer. However Lucie remembered the visit differently as she simply remembered Suzanne’s anguished questions as to who would look after her son and on hearing those tormented pleas had volunteered to take up the burden that Suzanne had borne for such a long time. Who knows what the true version of events was, but for sure it was easy to realise that it was the start of a contest for who should bear the responsibility for looking after Maurice Utrillo. When Suzanne had planned a wife for Maurice she always believed she could still control him and his life. She wanted a compliant wife for Maurice one whom she could manipulate. However she realised right from the start that Lucie Valore was not a person she could control or manipulate and so she desperately tried to end the relationship. It did not work for Maurice made the decision to rid himself of the Montmartre life and replace it with a life with the banker’s widow. Maurice Utrillo and Lucie Valore were married in a civil ceremony at the Montmartre mairie and later in a religious ceremony at Angoulème. Although Suzanne was present at the civil ceremony she refused to attend the religious one.

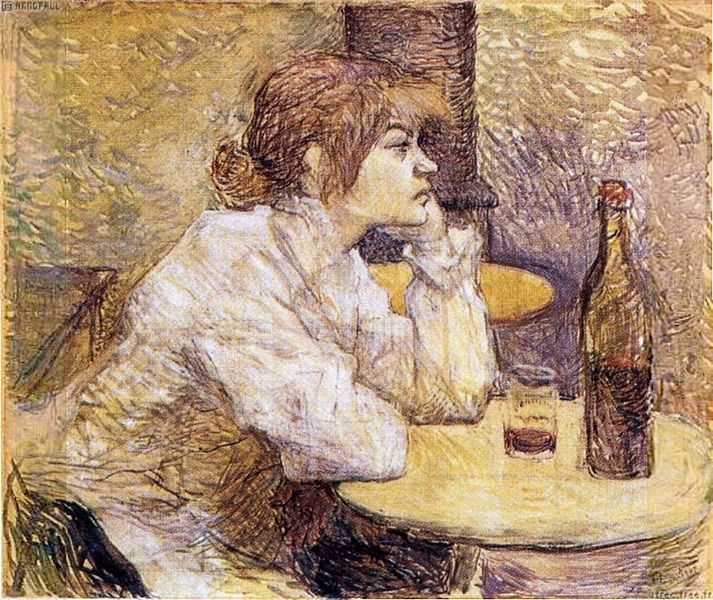

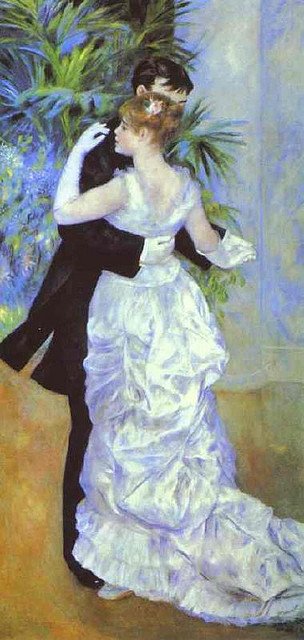

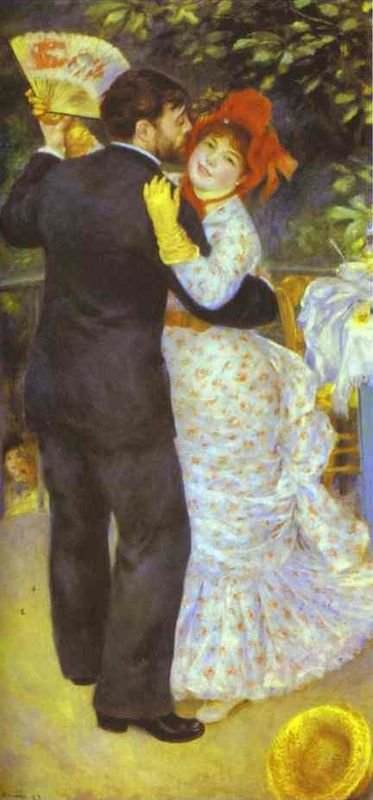

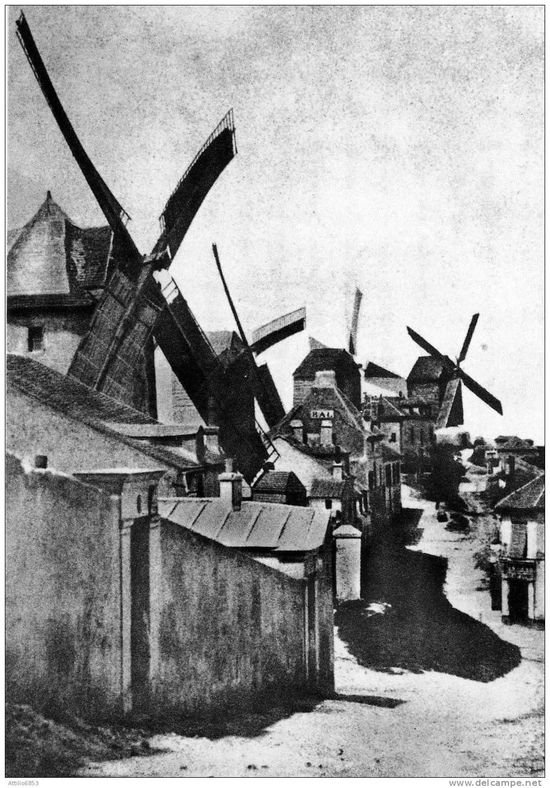

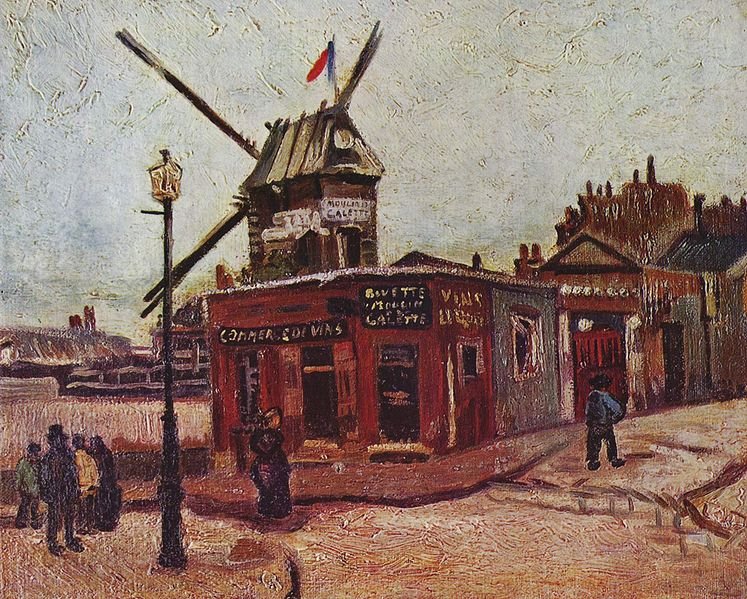

The newlyweds remained in Angoulème for twelve months and Lucie took on both the role as Carer for Maurice but also as his business manager which had once been looked after by André Utter. Lucie in a way controlled Maurice by carefully rationing his alcohol consumption so that it would not affect his artistic output. Lucie was an astute business manager as she controlled the output of his work to the art dealers so as to artificially raise the value of his paintings. His paintings grew in value and with this increased income the couple bought a large house with extensive grounds in the fashionable town of Le Vésinet, to the north west of Paris. Despite Lucie’s attempts to win over the support of Suzanne, her attempts failed and slowly Suzanne’s contact with her son lessened. Although she was aware that Lucie had controlled Maurice’s outbursts it could be that she resented the fact that Lucie had succeeded where she had failed. Suzanne had lost her mother, her husband and now her son what was left in her life? The answer came in the form of another young aspiring artist, Gazi. He was a young man with a swarthy collection and rumour had it that he was the son of a mogul emperor. Locals referred to him as Gazi the Tartar but for Suzanne he was simply a young artist from Provence whom she befriended. He eventually lived with her and looked after her like a devoted son with his mother. He would sit with her in the evenings and listen to her tales of the past, about Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Renoir and the little Master, Degas.

In May 1937 Suzanne was invited to attend the Women Painters Exhibition at the Petit Palais in Paris. She had several of her latest paintings on show as well as some of her earlier work. It was a celebration of French female artists and along with her works were paintings by Vigée le Brun, Berthe Morisot, Eva Gonzalèz and Sonia Turk. She spent hours critically viewing all the works of art and that evening she spoke to a friend who had accompanied her to the exhibition:

“…You know, chérie, I often boasted about my art because I thought that was what people expected – for an artist to boast. I’m very humble after what we have seen this afternoon. The women of France can paint too. But do you know, chérie, I think God made me France’s greatest woman painter…”

In April, 1938, Suzanne Valadon was sat before her easel painting a floral still life when she was struck down by a stroke. Neighbours heard her cry out and rushed inside to help her and found her lying motionless on the studio floor. She was rushed to hospital but the next day, the 7th April1938, she passed away, aged 73. Her daughter in law, Lucie, took care of the funeral arrangements as her husband, Suzanne’s son, Maurice, was in a state of collapse at home in Le Vésinet. A funeral service was held at the Church of Saint Peter of Montmartre on April 9th. The church was crowded to see the old lady, the great painter, begin her last journey. Her husband André Utter was there and inconsolable. His once greatest love had finally achieved peace. She was buried in Cimetière parisien de St Ouen.

(Marie-Clémentine Valadon)

23 Sept 1865 – 7 Apr 1938

André Utter became the owner of the castle to the death of Suzanne Valadon in 1938. He sold it in 1945 and died in Paris a few years later in 1948. Suzanne’s son Maurice Utrillo died on 5 November 1955, and was buried in the Cimitière Saint-Vincent in Montmartre and not in the family grave as Suzanne had planned. In 1963, eight years after the death of her husband, Utrillo’s wife Lucie, founded the Association Maurice Utrillo, which housed a collection of documents and photographs recording the history of the lives of her and her husband as well as Suzanne Valadon and André Utter. Lucy Utrillo died in 1965.

When I started writing about the life and works of Suzanne Valadon I had no idea that it would stretch over seven separate blogs. The more I wrote the more fascinated I became and the more I read about her life. In the end I could not bear to leave out little bits of information I had just gleaned. At one point I had decided not to go into too much detail about her son, Maurice Utrillo, but I soon realised that as he played such a key role in Suzanne’s life, it was important that I examined his relationship with his mother and grandmother and later his relationship with Suzanne’s lover Paul Mousis and her husband André Utter.

What did you make of Suzanne’s life? Were you less sympathetic with her lot in life believing she brought all her problems upon herself? How did you feel about her relationship with her son Maurice? Did you blame her for paying too little attention to him when he was a young child and by doing so, allowed his mental issues to worsen irrevocably or do you think that once she had been told by the doctors that Maurice “would grow out of it”, it was all she had to go on? So can you empathise with her?

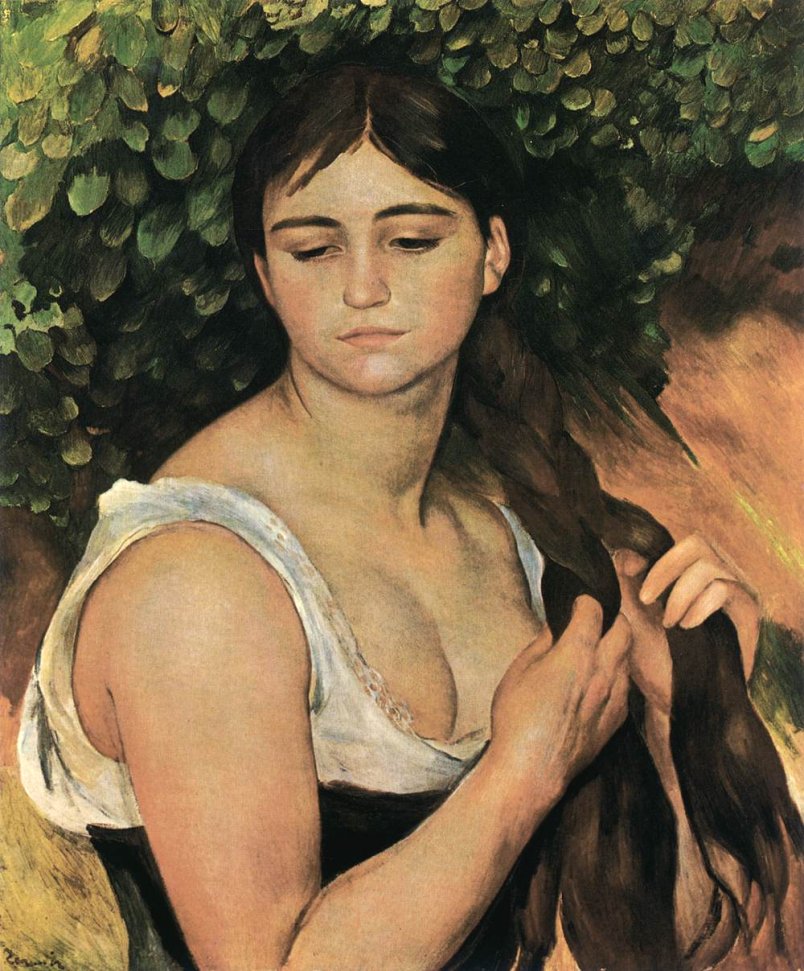

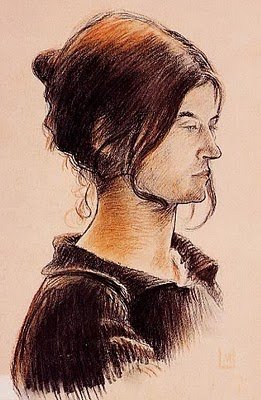

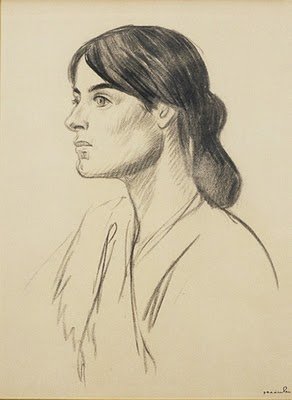

For me, I felt sadness for her when she realised she was losing her greatest asset, an asset that in so many ways shaped her life. The asset was her beauty but as we all know, one cannot hold on to it forever.

—————————————-

Most of my information came from a book I read on the life of Suzanne Valadon entitled The Valadon Drama, The Life of Suzanne Valadon, written by John Storm in 1923.

Other sites I visited to find some pictures were:

http://lapouyette-unddiedingedeslebens.blogspot.co.uk/

http://youngbohemia.blogspot.co.uk/2012/01/suzanne-valadon_8445.html

The Blog: It’s about time : http://bjws.blogspot.co.uk