Gertrude Horsford Fiske

The artist I am looking at today is the nineteenth century American painter Gertrude Horsford Fiske who was famous for painting people, still life, and landscapes. Gertrude Fiske was born into an established New England family that can trace their family history way back to the Governor of Plymouth Colony, William Bradford an English Puritan Separatist originally from the West Riding of Yorkshire in Northern England who moved to Leiden in Holland in order to escape persecution from King James I of England, and then emigrated to the Plymouth Colony on the Mayflower in 1620. Gertrude, born in 1879, was one of six children born into a wealthy Boston family, her father being an eminent lawyer. She was educated in Boston’s best schools but during her teenage years she showed little interest in art as much of her free time was taken up with horse riding and golf. She proved herself to be an extremely skilled professional golfer.

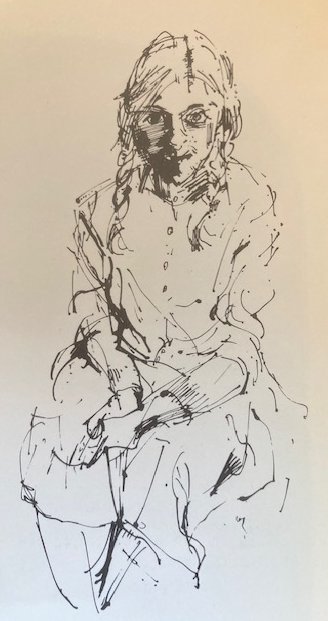

Woman in White by Gertrude Fiske

It was not until she was twenty-five years old that she took an interest in art and began to look at the possibility that her future could be as a professional artist. In 1904 she enrolled on a seven-year course at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, (now the art school of Tufts University), where her tutors included Edmund C. Tarbell, an American Impressionist painter, Frank Weston Benson, known for his Realistic portraits, American Impressionist paintings, watercolours and etchings and Philip Leslie Hale, an American Impressionist artist, writer and teacher.

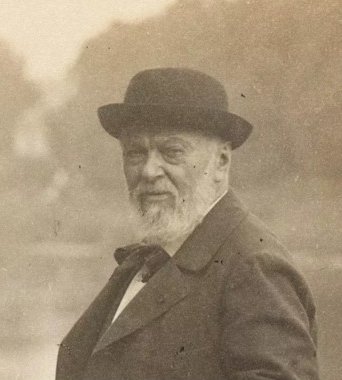

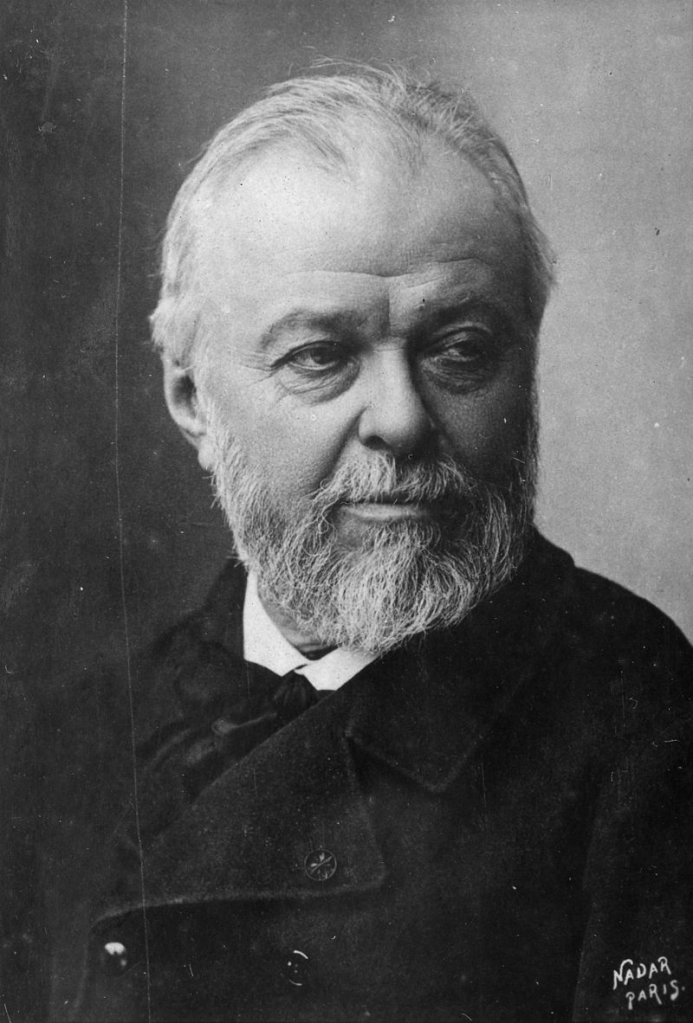

Charles Herbert Woodbury by John Singer Sargent (1921)

During the summers, she attended Charles Herbert Woodbury’s art classes in Ogunquit, Maine. Ogunquit was originally populated by The Abenaki indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands of Canada and the United States and in their language the name of the town means “beautiful place by the sea”. In the early years of the twentieth century, it had become a popular destination for artists who wanted to capture the landscape’s natural elegance.

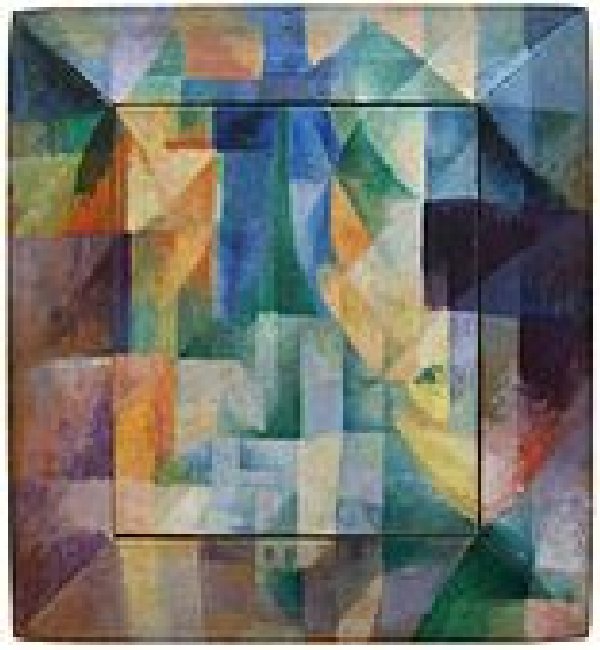

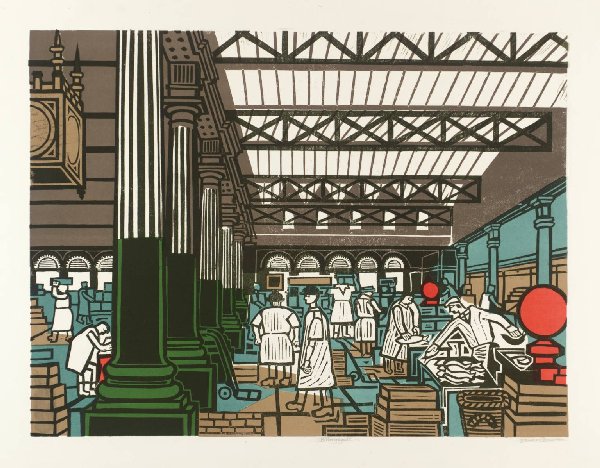

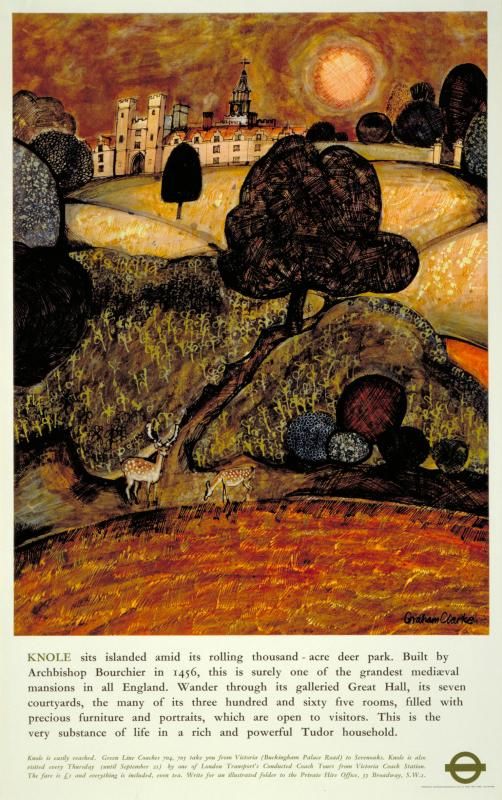

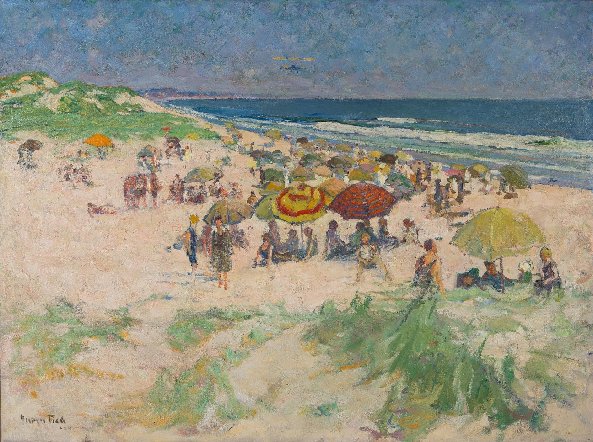

Ogunquit Beach by Gertrude Fiske (1914)

Ogunquit Beach by Gertrude Fiske

Soon, a community of artists formed the Ogunquit Summer School of Drawing and Painting which was founded by Charles Woodbury. Woodbury was a great influence on Gertrude Fiske’s informative years and he encouraged her and her fellow students to “paint in verbs, not in nouns.” By this, he meant that his students should enter into the life of the things they painted. He wanted to inspire them to fresh, “active” seeing and expressive creativity and told them that in seascapes they did not draw what they saw of the wave – you draw what it does. The phrase implied that painting is perceptual and that realism is evidence of the felt and the seen and not just of what’s visible.

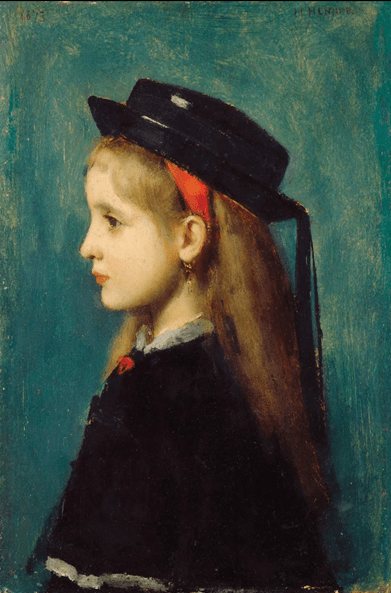

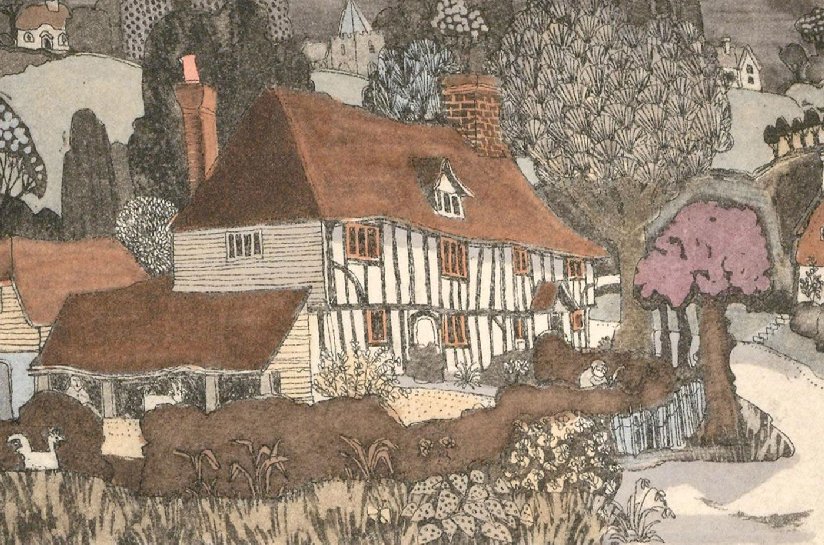

Bettina by Gertrude Fiske (1925)

Because of the family’s wealth, Fiske had the financial freedom to pursue her painting career and after she completed her time at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in 1912, she spent time in France, continually sketching as she travelled. Her artistic style was a blend of the light-filled, classical, portrait style she had mastered under Edmund C. Tarbell with the freer, inventive, and colour-rich landscapes she had learnt during her summers spent at the Ogunquit school.

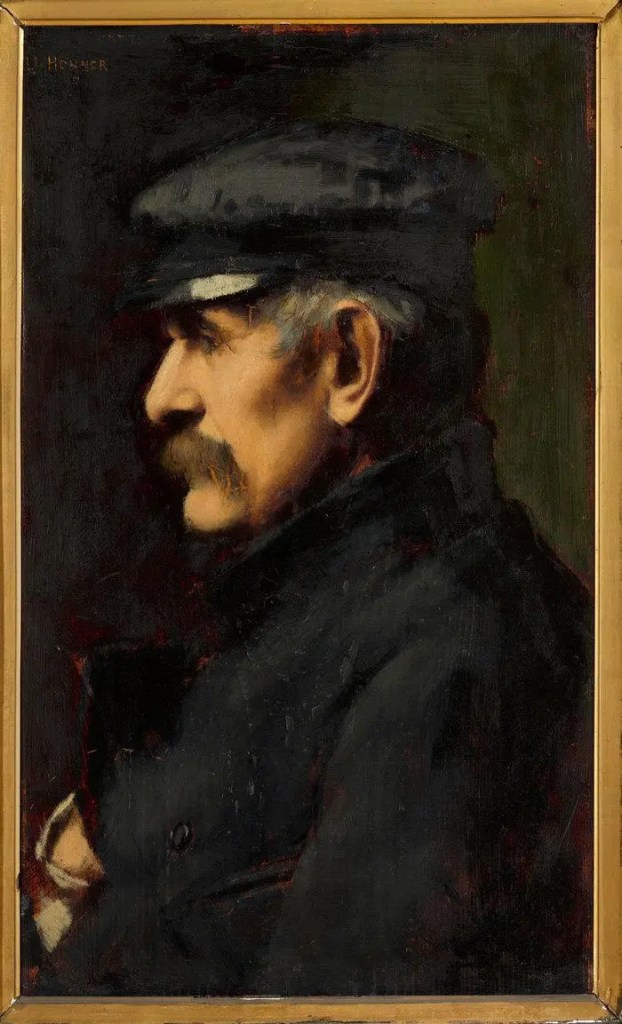

Nude in Interior by Gertrude Fiske (c.1922)

Gertrude Fiske painted a number of works featuring nudes. Her painting entitled Nude in Interior was completed around 1922. The subject of this work, the nude female, is shown posing for the artist, the image of whom we see in the background, reflected in a mirror. Gertrude often used this inclusion as a means to put over to the viewers the importance of the painter.

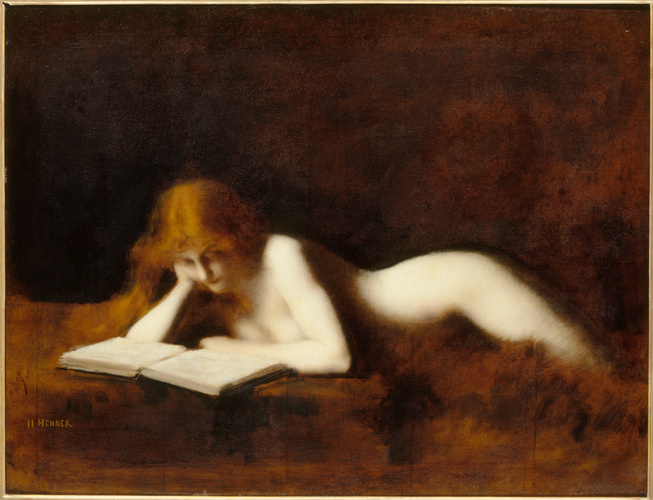

Bird of Paradise, Sleeping Nude by Gertrude Fiske (c.1916)

Another controversial nude work was her 1916 painting entitled Bird of Paradise, Sleeping Nude which received mixed reviews. It was praised for its honesty but more conservative critics said it was a scandalous depiction. Before us we see a foreshortened figure of a naked woman who appears supremely relaxed and unaware of us, the viewers. It is simply an honest depiction of a real woman.

Zinnias by Gertrude Fiske (c.1920)

Gertrude returned to America but tragedy struck her family with the deaths of a sister, brother and mother around the time that the First World War was raging in Europe. Fiske then had to care for her aging father. However, despite the tragic losses and her new role as a carer she continued to be a prolific and much-admired painter. She kept a studio in Boston as well as at her family’s longtime home, Stadhaugh, in the town of Weston, fifteen miles west of Boston. It was at Stadhaugh that she worked in her studio which was located on the top floor of a converted barn. It had a picturesque setting overlooking woods and this vista served as the backdrop for several of her works.

By the Pond by Gertrude Fiske (c.1916)

In 1914, she, along with prominent painters of the day, including Edmund Tarbell, William Paxton and Frank Benson, helped create the Guild of Boston Artists. Its mission was to promote both emerging and established artists who lived in the region. The Guild developed a reputation for excellence in quality and presentation. Later, in 1917, Gertrude was part of setting up the Boston Society of Etchers and in 1918 Fiske became a member of the National Association of Women Artists.

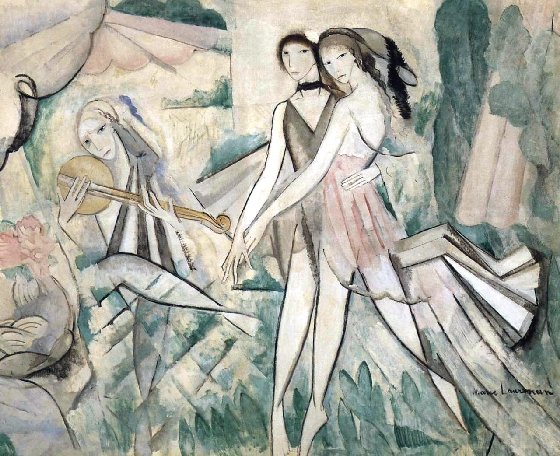

Strollers by Gertrude Fiske (c.1926)

After the end of the First World War, America staged a rapidly growing industrial way of life and along with waves of immigration in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, elements of a new national consciousness arose in the United States. It was considered to be part of the colonial revival, which found expression in architecture, decorative arts, paintings, and all types of material life which represented an effort to regain a sense of an earlier time in America. Boston was in the forefront of colonial revivalism, and it was the Boston School of Painting, led by Edmund C. Tarbell, that is closely identified with the movement. Gertrude Fiske, who had spent seven years there as a full-time student at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, was trained in this artistic dream of the future.

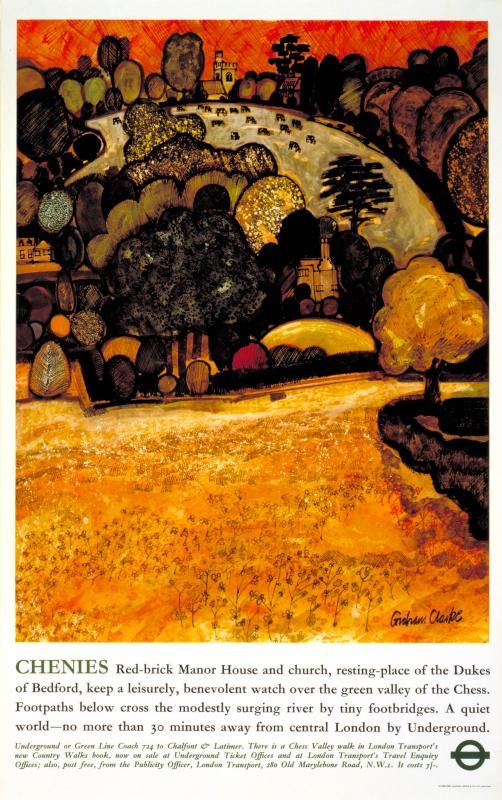

Wells, Maine by Gertrude Fiske

However Fiske was an independently minded and instead of blindly following social convention and the strong direction proposed by the Boston school with its more genteel mannerisms, she ploughed her own furrow and in her landscape depictions instead of removing signs of industry and technology from her work, she made a conscious decision to include them. A good example of this can be seen in her painting entitled Wells, Maine, in which she has retained depictions of a line of utility poles, with a secondary electrical line running across the painting. Her composition with utility poles set against the background of a seascape demonstrates the artist’s interest in juxtaposing signs of modernity with scenes more traditionally considered beautiful.

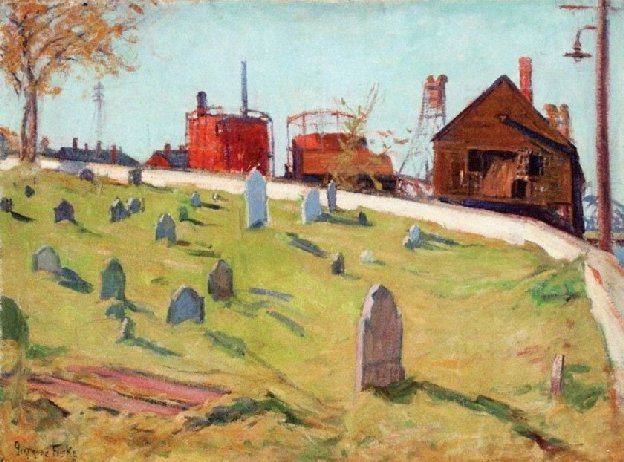

Portsmouth Burying Ground by Gertrude Fiske (c.1925)

Another example of Fiske’s urban landscape work is one she completed around 1932 entitled Portsmouth Burying Ground which depicts Portsmouth, New Hampshire’s oldest cemetery, known as the Point of Graves, which is situated on the banks of the Piscataqua River in the south end of town. This small historic cemetery dating to the 17th century was the final resting place for many of Portsmouth’s prominent residents. It is the oldest known surviving cemetery in Portsmouth, and one of the oldest in the state, which has about 125 gravestones. Whereas many landscape painters would have spent time amidst the beauty of the countryside Gertrude has chosen this discordant, working waterfront to position her easel to take in the surrounding land. Fiske confounded viewers of this work when she depicted the bright red gasometers and the Sheafe warehouse as a backdrop to the ancient burial ground.

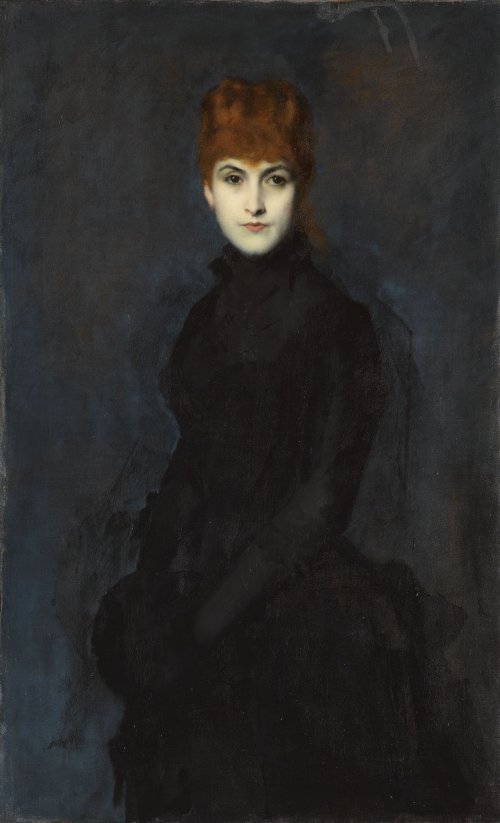

Portrait of William by Gertrude Fiske (1930)

One of her best-known figurative works was one Gertrude completed in 1930 entitled Portrait of William which she exhibited at both the Boston Art Club’s Annual Winter Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting and at the National Academy of Design’s 105th Annual Exhibition. It is part figurative and part an interior depiction which was a popular concept favoured by many of the early Boston School teachers and yet she put her own mark on the composition by her use of colours, such as the juxtaposition of the green of the fabric on the pillows with the dotted Swiss cotton of the woman’s purple dress. She also adopts an unusual placement of figures and objects in the work.

The Carpenter by Gertrude Fiske (1922)

Gertrude Fiske was appointed as the first woman ever to the Massachusetts State Art Commission in January 1930. She was also the the founder of the Concord Art Association. In an article in January 1930’s Boston Globe it was written that she had always had a strong artistic individuality of her own, and there is a note of personal distinction in all of her work—a virile note.

Fiske died in 1961 in Weston, Massachusetts aged 82.