The Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool has one of the most significant and famous collection of artworks in the UK, which includes European Renaissance paintings, masterpieces by Rubens, Rembrandt, Turner and Stubbs, Pre-Raphaelite artworks by Rossetti and Millais, Impressionist works by Monet and Degas and contemporary works by Hockney, Wylie and the winners of the John Moores Painting Prize. I have covered many of the Pre-Raphaelite works exibited here in previous blogs and following a visit I made to the gallery last week I have chosen a few more paintings which impressed me.

Lady in Black Furs by Pilade Bertieri (1912)

The first painting, I am showcasing is Lady in Black Furs, a work by the Italian painter Pilade Bertieri, which he completed around 1912. Bertieri was born in Turin and exhibited in major cities in Italy, in New York and notably Manchester and Liverpool as well as Paris at the Salon from 1907 to 1931. The painting depicts Bertieri’s wife Genevieve Wilson, the daughter of a wealthy New York socialite. It was during a voyage in 1905 from Italy and America that they met and a year later they got married. Bertieri said that he was first attracted to Genevieve when he saw seated on a deckchair. For him, her graceful composure was just too much to resist and this depiction is a reconstruction of his first view of her but this time in a more fashionable chair. The fact that she is wearing the very same furs, shoes and velvet and satin dress as she did aboard the ship in 1912 evokes memories for him of that first meeting. At the time of the painting Genevieve was pregnant with their first child.

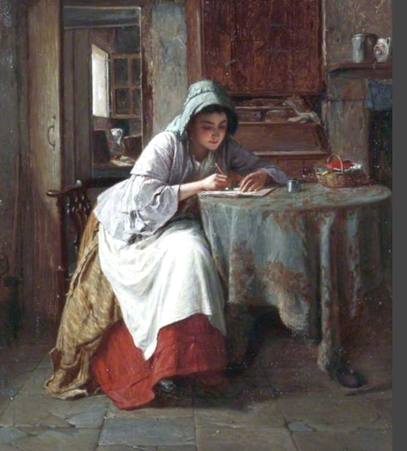

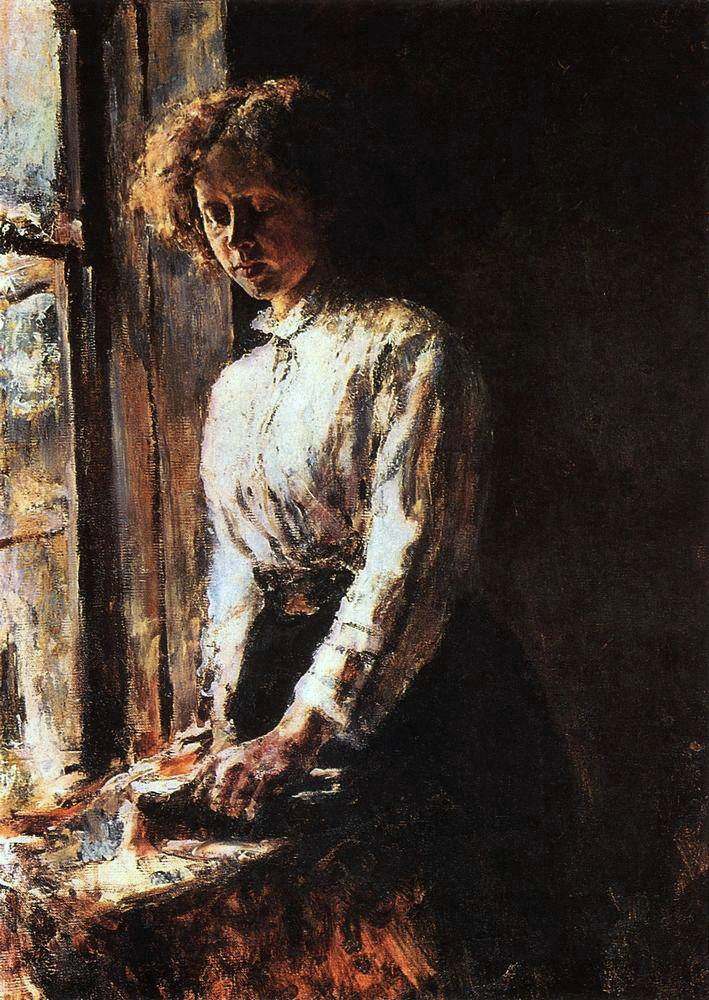

Fantine by Margaret Bernardine Hall (1886)

Margaret Bernadine Hall completed her painting entitled Fantine in 1886 and it depicts the character Fantine who was featured in Victor Hugo’s novel Les Misérables. Fantine was dismissed from her job because of her illegitimate child and was forced into the life of a sex worker in order for her and her daughter to survive. In the depiction we see Fantine protectively watching over her sleeping daughter.

Margaret Bernadine Hall was an English painter, born in 1863 in Wavertree, Liverpool. Her father was Bernard Hall, a merchant, local politician and philanthropist, who was elected Mayor of Liverpool in 1879. Her mother was Margaret Calrow from Preston, who was Bernard Hall’s second wife. Margaret was their second child, and their oldest daughter. In 1882 the family moved to London but at the end of that year nineteen-year-old Margaret went to live and study in Paris. Between 1888 and 1894 she travelled extensively to countries including Japan, China, Australia, North America, and North Africa, returning to live in the French capital in 1894. She moved back to England in 1907, where she died three years later.

River Scene with a Ferry Boat by Salomon van Riysdael (1650)

One of my favourite landscape painters is Salomon van Ruysdael and in his painting entitled River Scene with a Ferry Boat we see the kind of work he produced for the art-loving public. At this time, artists had mostly depicted religious subjects in their paintings and the Catholic Church used to be most artists’ best client, as they ordered altarpieces and other artworks to decorate churches and sacred places, but this came to an end with the Reformation as many Protestants refused to allow the presence of religious paintings or sculptures in churches. This led to a great crisis for artists in Northwestern European countries as artists had only a few ways left to make money: painting portraits and illustrating books but there was also a revival of landscape paintings. As well as the ever popular genre scenes, people began to buy landscape paintings to decorate their homes. Jacob Isaackszoon van Ruisdael, Salomon’s nephew, is generally considered the pre-eminent landscape painter of the Dutch Golden Age, a period of great wealth and cultural achievement when Dutch painting became highly popular. Jacob was best known for his atmospheric river scenes based upon the countryside around the city of Haarlem where he lived. He was also a merchant who dealt in the blue dye that was used in Haarlem’s famous cloth bleaching factories.

The Walker Art Gallery houses Salomon’s painting entitled River Scene with a Ferry Boat and we see a ferry crossing the river laden with people, livestock and even a small cart. These ferries were an essential feature of the watery Dutch countryside, and a popular subject with landscape painters such as the Ruysdael family. This work is typical of much 17th-century Dutch landscape painting: naturalistic in its clear light and cloudy, rain-washed sky, but at the same time carefully organised to achieve a balanced composition. This work despite looking as though it was painted en plein air was not painted outdoors. It is an idealised depiction and probably does not represent any particular place but is an amalgam of various details and features from a number of different places juxtaposed to form this vista. Close to the riverbank we see a smaller boat with busy pulling in a fishing net. On the bank is a barn in which workers are salting fish and putting them into barrels. On top of the barn is a large dovecot. In a way the painting is a ‘foodscape’ as well as a landscape, highlighting what nature has to offer. The Dutch patrons liked this kind of narrative painting.

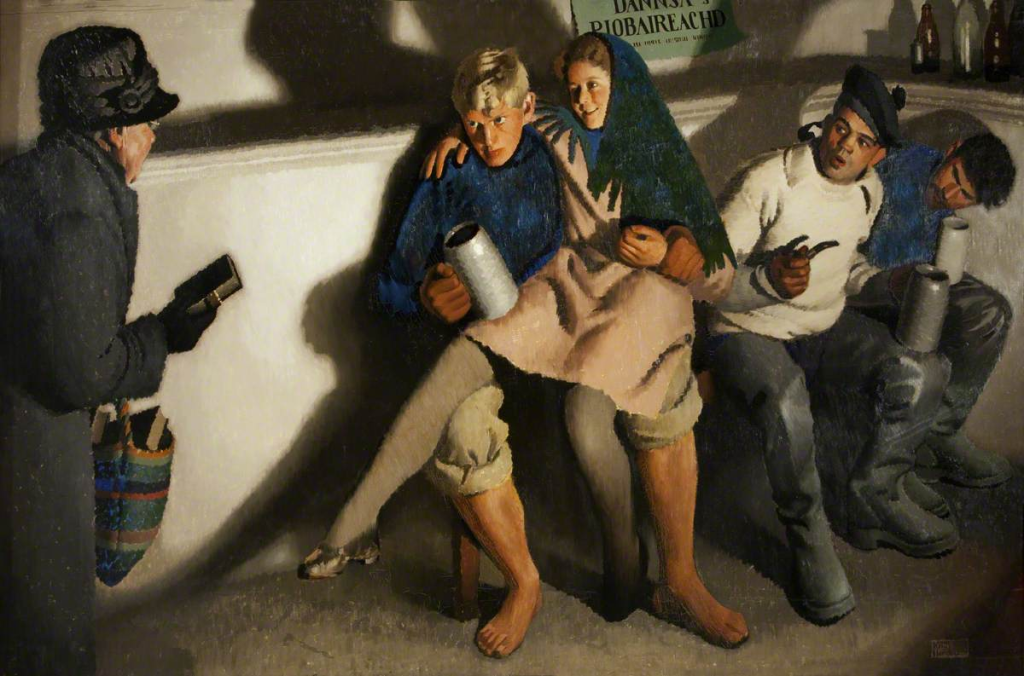

The Fortune Teller by Jan Steen (1663)

One of the greatest Dutch genre painters was Jan Steen. In Holland he ranks next to Rembrandt, Vermeer, and Hals in popularity. He is best known for his humorous genre scenes, warm hearted and animated works in which he treats life as a vast comedy of manners. Steen was born in Leiden and is said to have studied with Adriaen van Ostade in Haarlem and Jan van Goyen (who became his father-in-law) in The Hague. He worked in various towns – Leiden, The Hague, Delft, Warmond, and Haarlem and in 1672 he opened a tavern in Leiden. In his painting The Fortune Teller we see a young woman sitting by her spinning wheel having her fortune told. One interpretation of this depiction is that she is a sex worker, the old, black hooded lady is the brothel keeper and the soldiers in the background are her clients. Fortune-telling was strongly associated with deceit, and therefore frowned upon in the seventeenth century.

The Epte in Giverny by Claude Monet (1864)

Modiste Decorating a Hat by Edgar Degas. (c.1895)

My next two offerings, The Epte in Giverny, by Monet and Modiste Decorating a Hat by Degas, are new arrivals at the gallery thanks to the beloved taxman. They have been acquired by National Museums Liverpool through the Government’s Acceptance in Lieu scheme which allows people, who have Inheritance tax bills to pay, to transfer important works of art and heritage objects into public ownership which are then allocated to museums, archives or libraries for people to enjoy. Both the Monet and Degas artworks come from the collection of Mary Elliot-Blake and have been owned by the Montagu family by descent. Due to the family’s connection to Liverpool, the paintings were allocated to the Walker Art Gallery.

Monet completed the painting, The Epte in Giverny, in 1884, and it depicts the fast-flowing Epte river, which rises in Seine-Maritime in the Pays de Bray, near Forges-les-Eaux and empties into the Seine not far from Giverny where the artist painted his famous water lily series.

The second work is by Degas’ entitled Modiste Decorating a Hat and depicts a milliner adjusting a hat in a shop window.

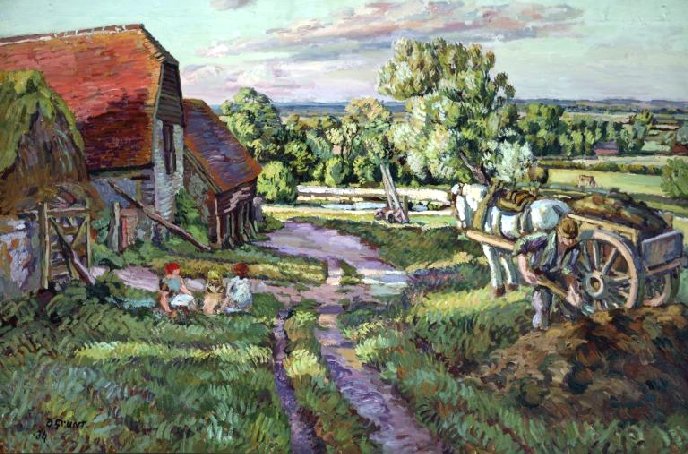

Farm in Sussex by Duncan Grant (1934)

The 1934 painting, entitled Farm in Sussex, is a depiction of Charleston Farm at Firle in Sussex is by the artist Duncan Grant. The picture was painted in his studio over a period of several years. The first thing that strikes you about the depiction is the unusually bright colours he has used and this is due to Duncan Grant’s great interest in Fauvism, which was popular between 1905 and 1910. The Fauves (the Beasts) used bright, clashing colours and fierce brushstrokes to express feelings and emotions. In 1909, Grant met Henri Matisse, who was a leading light of this group.

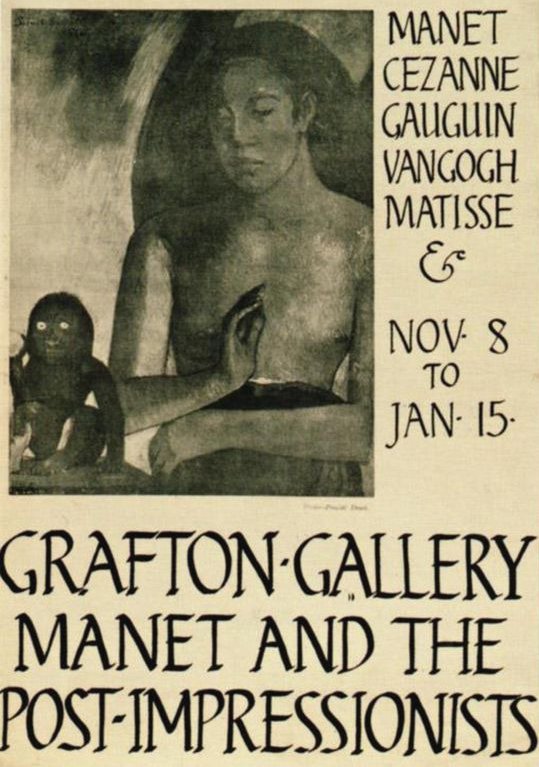

He also saw more of the groups work in Roger Fry’s Post-Impressionist exhibition in London in November 1910, Fry had organised the exhibition Manet and the Post-Impressionists at the Grafton Galleries, London. This exhibition was the first to prominently feature Gauguin, Cézanne, Matisse, and Van Gogh in England and brought their art to the public.

Duncan Grant lived at Charleston Farm from 1916 with Vanessa Bell (neé Woolf), who was an artist and the sister of Virginia Woolf. They had met through the Bloomsbury Set, a London-based group of artists and writers who met regularly to discuss their work and ideas about modernism and art. Charleston Farm became a meeting place for the Bloomsbury Set outside of London. The pair had moved to the countryside from London following the outbreak of World War I so that Grant could avoid conscription by working as a farm labourer. The couple each had their own studio at the farmhouse and decorated the entire building, including walls, fireplaces, door panels and furniture, with their paintings, fabrics and ceramics. They kept the house after the war and used it as a summer home. The painting highlights the bright colours that characterise Grant’s work. The painting was completed in 1934, the same year that Roger Fry died. Fry had been a close friend of both Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell and was a regular visitor to Charleston. The painting reflects Grant’s affection for the Farm and the people he associated with it

The Murder by Cezanne (c.1870)

The Murder is one of Cézanne’s early paintings which he completed around 1870. It is a dark and highly melodramatic work which ably communicates the brutality of the act. In the depiction we see the murderer raising his hand and is about to give the final strike while his female conspirator forcefully holds down the rounded heavy-set body of the female victim whilst the fatal blow is struck. Little can be made out of the figures; just the outline head and arms of the victim whose facial expression is contorted with pain. The faces of her two assailants are blurred. Cezanne was not interested with the identities of the murderers but the scene simply depicts the heinous act of anonymous violence. The scene is made more frightening by the bleak surroundings and the dark sky overhead. Close to the figures is a riverbank and we can deduce that the body of the dead woman will eventually be dumped into the dark waters.

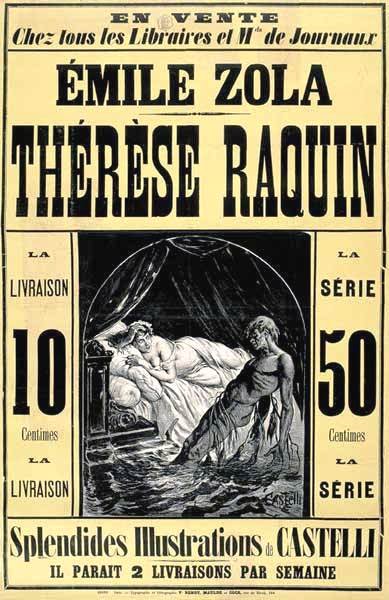

Publicity Poster for Zola’s novel

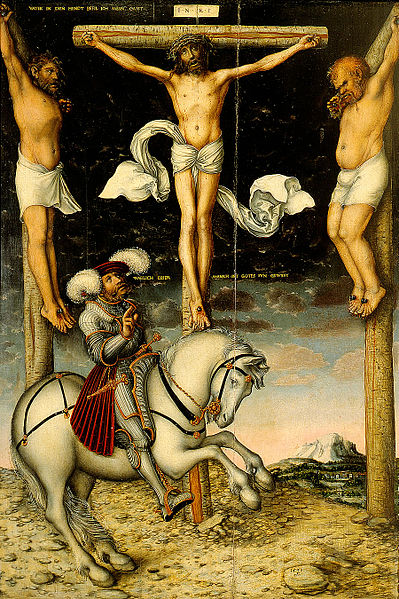

The Murder was painted at a time when Cézanne was still influenced by the Old Masters such as Eugene Delacroix and Francisco Goya, and Diego Velazquez. So after painting so many colourful landscapes why would he depict a brutal murder? It is thought that Cezanne’s choice of depicting this brutal subject may have been inspired by Emile Zola’s novel Thérése Racquin which had been published in 1867, in which the heroine murders her husband. It was Zola’s third novel, though the first to earn wide fame. The novel’s adultery and murder were considered scandalous and famously described as “putrid” in a review in the newspaper Le Figaro. The painting’s subject could also be inspired by illustrations in the popular press.

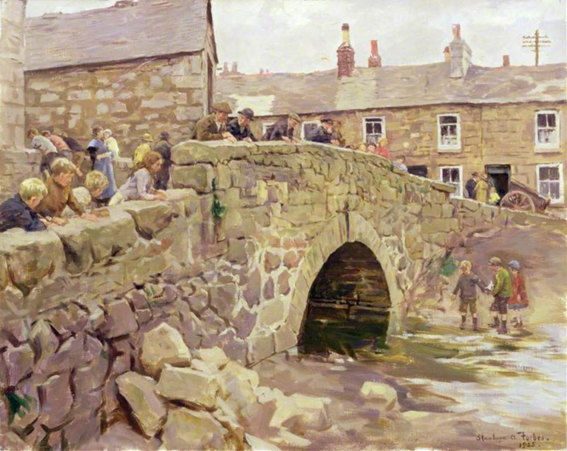

A Street in Britanny by Stanhope Forbes (1881)

My final painting is A Street in Brittany by Stanhope Alexander Forbes which he completed in 1881. It is a depiction of figures in a narrow street: women in white headgear known as coiffes and blue petticoats. They are grouped around their cottages, some are seated on their knitting blue jerseys for their fishermen husbands.

Stanhope Forbes was born in Dublin, the son of Juliette de Guise Forbes, a French woman, and William Forbes, an English railway manager, who was later transferred to London. He was educated at Dulwich College, and he studied art under John Sparkes at Lambeth College of Art, who later taught at South Kensington School of Art. Forbes then studied at the private atelier of Léon Bonnat in Clichy, Paris from 1880 to 1882. It was in the French capital that Forbes met up with fellow artist, Henry Herbert La Thangue, who had also attended Dulwich College, Lambeth School of Art and the Royal Academy.

In 1881 Forbes and La Thangue went to Cancale, a village in Brittany, at the western end of the bay of Mont-Saint-Michel, fifteen kilometers east of Saint-Malo. It was here that Forbes began to paint en plein air and produced this painting.

His biographer, Mrs. Lionel Birch in her 1906 book Stanhope A. Forbes, A. R. A., and Elizabeth Stanhope Forbes, A. R. W. S. recalled the setting of this work:

“..One of the first results of the visit to Cancale was a composition of figures in a narrow street: women in white coiffes and blue petticoats, grouped round their cottages and seated on their doorsteps engaged in their everlasting occupation of knitting blue jerseys for their fisher husbands…”

The biographer continues:

“…It was a very simple motif, but painted with great care and conscientiousness, and with a close and searching attention to those truths of lighting and that clear out-of-door aspect which the painter sought to betray. It was interesting, too, as the first attempt Stanhope Forbes had made in what might be termed figure composition, if, indeed, a picture in which there is so little of arrangement in the grouping of the figures can be termed a composition. But it was, at any rate, a great step from simple portraiture, and its success — for it brought the young painter a very signal one — had the most marked influence in determining his future. Exhibited at the Royal Academy of 1881, it attracted favourable attention, and when, later on, it was sent to Liverpool, the Committee of the Walker Art Gallery decided to purchase it for their permanent collection…”

Forbes left France and returned to London and exhibited the works he had made in Brittany at the 1883 Royal Academy and Royal Hibernian Academy shows. In 1884 he moved to Newlyn in Cornwall, and soon became a leading figure in the growing colony of artists.

I hope this blog will tempt you to visit the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool. You will not be disappointed.

An example of this is the preliminary sketch of the reclining man, dressed in brown, we see at the bottom left of the Fête Galante painting. This sketch can be found at the Ackland Art Museum, which is part of the University of North Carolina, at Chapel Hill.

An example of this is the preliminary sketch of the reclining man, dressed in brown, we see at the bottom left of the Fête Galante painting. This sketch can be found at the Ackland Art Museum, which is part of the University of North Carolina, at Chapel Hill.

The Casa de Iberoamérica, House of Ibero-America in Cadiz is located in the 18th-century building on Concepción Arenal Street on the edge of the Old Town of Cadiz. It was once the building that housed the Royal Prison. The foundation stone for the building was laid in 1794 but it was not completed until 1836. The buildings remained a prison until 1966 when it was abandoned. Subsequently, it was decided to use it as a courthouse thus preventing it from becoming a crumbling ruin. In 2006 the building was returned to the City Council, and in January 2011 it became the Casa de Iberoamérica.

The Casa de Iberoamérica, House of Ibero-America in Cadiz is located in the 18th-century building on Concepción Arenal Street on the edge of the Old Town of Cadiz. It was once the building that housed the Royal Prison. The foundation stone for the building was laid in 1794 but it was not completed until 1836. The buildings remained a prison until 1966 when it was abandoned. Subsequently, it was decided to use it as a courthouse thus preventing it from becoming a crumbling ruin. In 2006 the building was returned to the City Council, and in January 2011 it became the Casa de Iberoamérica.

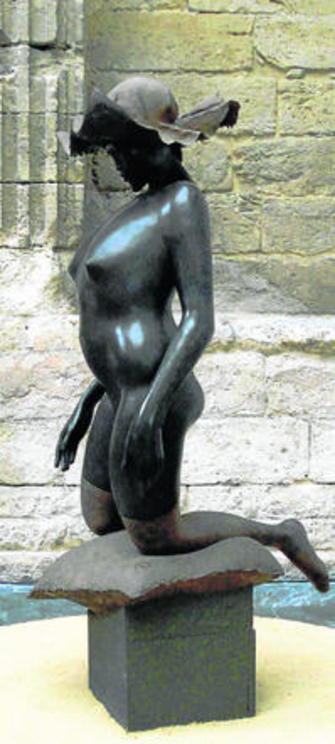

In 1948, Zitman settled in the northern Venezuelan coastal town of Coro, where he found employment as a technical draftsman for a construction company. In that same year, he married a Dutch lady, Vera Roos, whom he had first met in The Netherlands. The couple went on to have three children, Berend, Lourens and Barbara. Much of his free time was spent painting and creating sculptures. Later, in 1949, he moved to the city of Caracas, and the following year, he found work as a furniture designer at a factory of which he later became the manager. In 1951, he was awarded the National Sculpture Prize. In 1955 he was hired by the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism of the Universidad Central de Venezuela to teach courses in decoration, drawing, watercolour and gouache, which was then combined into a design workshop.

In 1948, Zitman settled in the northern Venezuelan coastal town of Coro, where he found employment as a technical draftsman for a construction company. In that same year, he married a Dutch lady, Vera Roos, whom he had first met in The Netherlands. The couple went on to have three children, Berend, Lourens and Barbara. Much of his free time was spent painting and creating sculptures. Later, in 1949, he moved to the city of Caracas, and the following year, he found work as a furniture designer at a factory of which he later became the manager. In 1951, he was awarded the National Sculpture Prize. In 1955 he was hired by the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism of the Universidad Central de Venezuela to teach courses in decoration, drawing, watercolour and gouache, which was then combined into a design workshop. In 1958, he exhibited a collection of drawings and paintings at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Caracas. That year, he decided to give up his life as a businessman and concentrate on his art and sculpture and moved with his family to the island of Grenada, where he dedicated himself completely to painting and began to affirm his style in sculpting.

In 1958, he exhibited a collection of drawings and paintings at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Caracas. That year, he decided to give up his life as a businessman and concentrate on his art and sculpture and moved with his family to the island of Grenada, where he dedicated himself completely to painting and began to affirm his style in sculpting. In 1961 he took part in an exhibition of Gropper Gallery in Boston. He returned to Holland, and studied foundry techniques with Pieter Starrevelt, in Amersfort, and then went back to Caracas where he was given the post as a design professor at the Architecture School of the Central University of Venezuela. In 1964 he converted an old sugar cane mill, known as a trapiche into his residence and workshop, in Caracas’ Hacienda de la Trinidad.

In 1961 he took part in an exhibition of Gropper Gallery in Boston. He returned to Holland, and studied foundry techniques with Pieter Starrevelt, in Amersfort, and then went back to Caracas where he was given the post as a design professor at the Architecture School of the Central University of Venezuela. In 1964 he converted an old sugar cane mill, known as a trapiche into his residence and workshop, in Caracas’ Hacienda de la Trinidad. In 1970, Zitman met Dina Viery, a Russian immigrant, and French art dealer, art collector and one time a model for the French painter and sculptor Astride Maillol whom she met in 1934. Viery was a great friend of Maillol during the last ten years of his life and when he died she helped establish the Musée Maillol art museum in Paris. From then on, Zitman dedicated himself exclusively to sculpture. More exhibitions of his work followed in Venezuela, France, Switzerland, the Netherlands, the United States, Japan and other countries, earning a host of national and international awards.

In 1970, Zitman met Dina Viery, a Russian immigrant, and French art dealer, art collector and one time a model for the French painter and sculptor Astride Maillol whom she met in 1934. Viery was a great friend of Maillol during the last ten years of his life and when he died she helped establish the Musée Maillol art museum in Paris. From then on, Zitman dedicated himself exclusively to sculpture. More exhibitions of his work followed in Venezuela, France, Switzerland, the Netherlands, the United States, Japan and other countries, earning a host of national and international awards. Zitman died on 10 January 2016 at the age of 89. Zitman earned numerous national and international awards for his work and in 2005 he was decorated with the Knight of the Order of the Netherlands Lion.

Zitman died on 10 January 2016 at the age of 89. Zitman earned numerous national and international awards for his work and in 2005 he was decorated with the Knight of the Order of the Netherlands Lion. I will leave you with a recent write-up from the Diario de Cádiz, a Spanish-language newspaper published in Cadiz, regarding the Cornelis Zitman’s permanent exhibition at the Casa de Iberoamérica in Cadiz:

I will leave you with a recent write-up from the Diario de Cádiz, a Spanish-language newspaper published in Cadiz, regarding the Cornelis Zitman’s permanent exhibition at the Casa de Iberoamérica in Cadiz: