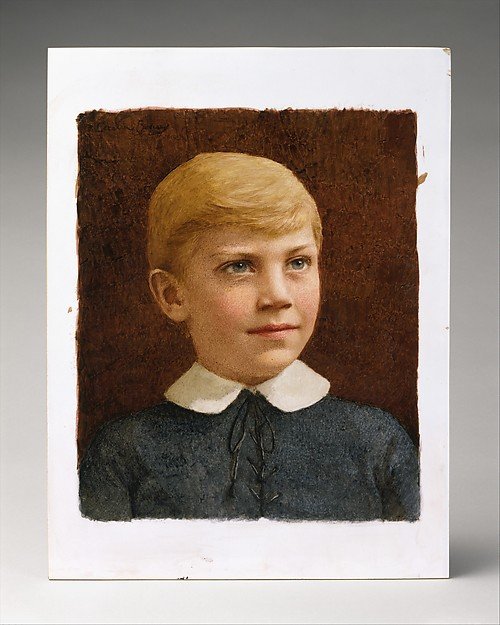

Upon returning to the United States, Beaux became one of the most sought-after portraitists in Philadelphia and New York. One of the first paintings by Cecilia Beaux, which was acclaimed by the critics for its gentle innocence, was a portrait she did for her friend and fellow artist, Rosina Emmet Sherwood in 1892. It was a portrait of her friend’s daughter Cynthia Sherwood. Rosina Emmet Sherwood was a book illustrator and one of the foremost female painter of that time and was a close friend of Cecilia’s. The two women had met through their connection with the arts, and in 1892 they wanted to celebrate their friendship by swapping portraits. Cecilia gave Rosina a portrait depicting her second child and eldest daughter, three-year-old Cynthia. The painting is made up of a tonal mixture of lilacs, crimson, and whites. In the work we see Cynthia sitting on a red sofa. She has a white ribbon in her hair and is wearing a white pinafore over a blue-grey dress and her arms rest in her lap. Rosina was delighted with her daughter’s portrait which was exhibited at the 1895 Society of American Artists’ annual exhibition. In a letter to Cecilia, Rosina wrote about how her daughter’s portrait was well received by fellow artists and critics alike:

“…My dear — you and Cynthia were the lions of the Exhibition yesterday. Really, much as I admired the picture, I was startled at its brilliancy and force…. It never looked so like Cynthia before. The artists all moved about it…. Mr. Chase said he would give anything to own it and Robert Reid, after extravagantly praising the big picture [Sita and Sarita] said he liked Cynthia’s portrait much the best. Kenyon Cox said that for the sort of portrait painting you chose to do, you do it better than any man he knew except John Singer Sargent. So there Madame!…”

In return Rosina painted a portrait of her close friend. Cecilia was so enamoured with the portrait that she kept it all her life and, on her death, it passed down to her great-niece.

Two years later, in 1894, Cecilia completed another portrait of a young girl, her two-year-old niece, Ernesta Drinker, entitled Ernesta (Child with Nurse). In the painting, we see the young girl holding the hand 0f her nurse, Mattie. The portrait of Cecilia’s young niece reveals the well-to-do world of the advantaged child. It is a sentimental portrait focusing on the first tentative steps of the young girl and if we look closely at the tightly clasped hands of adult and child, we see how Cecilia has depicted the partnership between the dependent child and the caring protective adult. We view the painting at the child’s eye-level. The figure of the nurse is cropped at the waist, and so we just see the arm and skirt of the nurse which makes us aware of the size of the diminutive child. From where we stand viewing the portrait, we soon realise that it is all about the world of the child. The portrait of young Ernesta was shown at the Society of American Artists in their spring exhibition in 1894. In 1896 the painting was awarded a third-place bronze medal at the Carnegie Art Institute’s first International exhibition.

Cecilia Beaux’s child portraiture was very popular and in much demand, but this was just one “string to her bow”. During the year in which she completed the portrait of Cynthia Sherwood she completed a portrait of an eminent man, The Reverend Matthew Blackburne Grier, who lived just two doors away from Cecilia’s family home. The subject of the painting is the retired Presbyterian clergyman and former editor of The Presbyterian who had come to live in West Philadelphia. Cecilia had approached him and asked if he would sit for her. In the portrait, we see him sitting in the tricornered Chippendale chair which was a much-used accoutrement of her studio. Within a year of its completion the painting became a prize-winning portrait, winning her the Philadelphia Art Club’s Gold Medal in 1893.

In May 1894, Cecilia Beaux was elected an associate of the National Academy of Design. Admission to this academy was conditional on her agreement to the Academy’s Constitutional rule that she must submit a portrait of herself for the Academy’s permanent collection. For Cecilia it was a moment in time that she must decide how she wanted to portray herself. She was now thirty-nine years old and had the self-confidence to believe that she was both good-looking and cultured and she decided that those characteristics needed to be depicted in the finished portrait. The completed Self Portrait also shows off her beauty. Her lavender, beige and white striped silk dress accentuated her elegance appearance. This is not a depiction which in any way exudes her sexuality. It is all about her professionalism and serious dedication to her art. Nobody could question her beauty but for Cecilia, she wanted to be remembered not for her physical attributes but for her exceptional artistic talent.

In 1895 Cecilia was appointed the “Instructor of the Head Class of the Schools,” at the Pennsylvania Academy with a salary of $1,200 a year. This appointment given to a female was the talk of the local newspapers. One newspaper commented:

“…Never before, either in this country or abroad, has a woman been chosen as a member of the faculty in a famous art school. It is a legitimate source of pride to Philadelphia that one of its most cherished institutions has made this innovation…”

Beaux taught at the Academy for two decades in either a “Head Course” or a “Portrait Class”. Her classes were mixed, and she was constantly pressing her female students telling them that they had to work twice as hard as their male students if they wanted to achieve success.

At the height of her long career, Beaux painted the cream of the American elite. She received commissions to paint portraits of the “great and the good” including college presidents, businessmen, socialites, eminent medical men and women, and political notables.

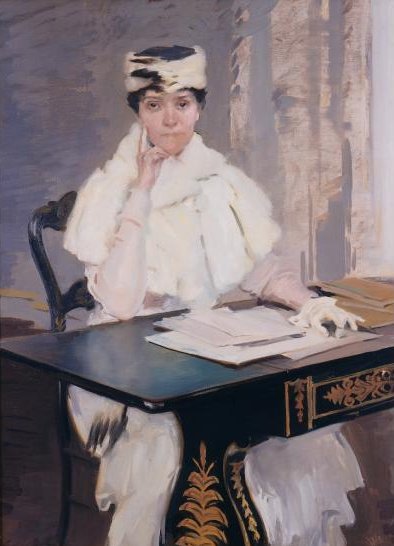

In 1897 she accepted a commission to paint a portrait of the former Anna Riddle, who was the wife of Thomas Alexander Riddle, an American businessman, railroad executive, and industrialist. He was the fourth president of the Pennsylvania Railroad. In this sumptuous portrait we see the fifty-eight-year-old lady adorned in a shimmering ivory-satin gown and white-lace cap. Her left hand holds on to a parasol which rests against her knee. Her right hand, suitably bejewelled as was becoming for such a wealthy lady, rests on a marble side table. On top of the table we can see a silver tea tray, a blue bowl of red geraniums, and a brown porcelain Chinese export teacup all of which help to portray the status and wealth of the sitter and her family. In the background we can just make out a faint sketching of a round table and chair.

Cecilia Beaux had received the commission to paint the portrait of Mrs Thomas Alexander Scott on the strength of her previous year’s bridal portrait of her daughter, Mary Dickinson Scott (Mrs. Clement B. Newbold), at the time of her wedding to Clement Buckley Newbold the wealthy banker and financier in 1896.

In the autumn of 1895 Cecilia was commissioned to paint a portrait of Dr. John Shaw Billings, a renowned surgeon and librarian, who had made significant contributions to the American medical profession. He sat for Cecilia at her Chestnut Street studio. It was his testimonial year and at a dinner honouring him he was presented with a silver box containing a check for $10,000, “in grateful recognition of his services to medical scholars”. The sum of money had been raised by 259 physicians of the United States and Great Britain. Money was also set aside for the commissioning of his portrait by Cecilia Beaux and it was later presented Beaux’s work to the Army Medical Museum and Library in Washington, D.C.

By 1900 the Cecilia Beaux’s work was in great demand and clients came from all over the east coast to sit for her and she decided she needed to base herself in New York. Richard and Helena Gilder were very close friends of Cecilia’s whom she had met through her former tutor Catherine Drinker and her husband Thomas Janvier. Richard Watson Gilder was a poet and editor of the periodicals Scribner’s Monthly and The Century Magazine, and the Gilders were leading lights of an artistic literary and music circle in New York and it was through Cecilia’s friendship with them that she had received many portrait commissions from the rich and famous. The Gilders lived in New York and during her protracted stays in the city she would stay with them. Eventually she got herself a studio on the corner of South Washington Square and Broadway, which was close to the Gilder’s house on East 8th Street.

Cecilia’s portraiture was so popular that she could be very circumspect on which commissions she chose to accept. She was once quoted as saying that it doesn’t pay to paint everybody, and by adhering to that rule she ensured that she became one of the most famous late nineteenth century American portrait artists whose clientele was mainly drawn from the upper class. One of her most famous sitters was, Edith Roosevelt, the second wife of the United States president, Theodore Roosevelt who sat for Cecilia 1n 1902.

Cecilia recalled the sittings for the portrait:

“… A number of visits to Washington were needed for the work, and the portrait was painted in the White House. It was to have been of Mrs. Roosevelt only, but her daughter Ethel consented to literally ‘jump in,’ greatly enlivening, I hope, her mother’s hours of attention to posing. This attention was constant and sympathetic, but not static, and did not need to be. They generously devoted the Red Room to me for a studio……………..… I chose — and upholstered — a covering for the broad seat on which Mrs. Roosevelt and Ethel could dispose themselves easily; the warmth of the Red Room got somehow into the picture, and fortunately we proceeded without many changes. I understood from the first that it was not to be an official portrait, and I think every one was satisfied that, as it was created among intimate circumstances, its spirit might be the same…”

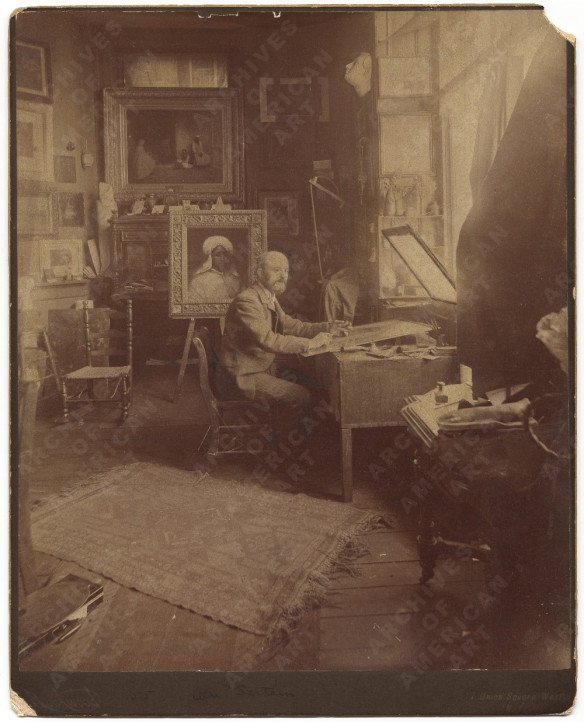

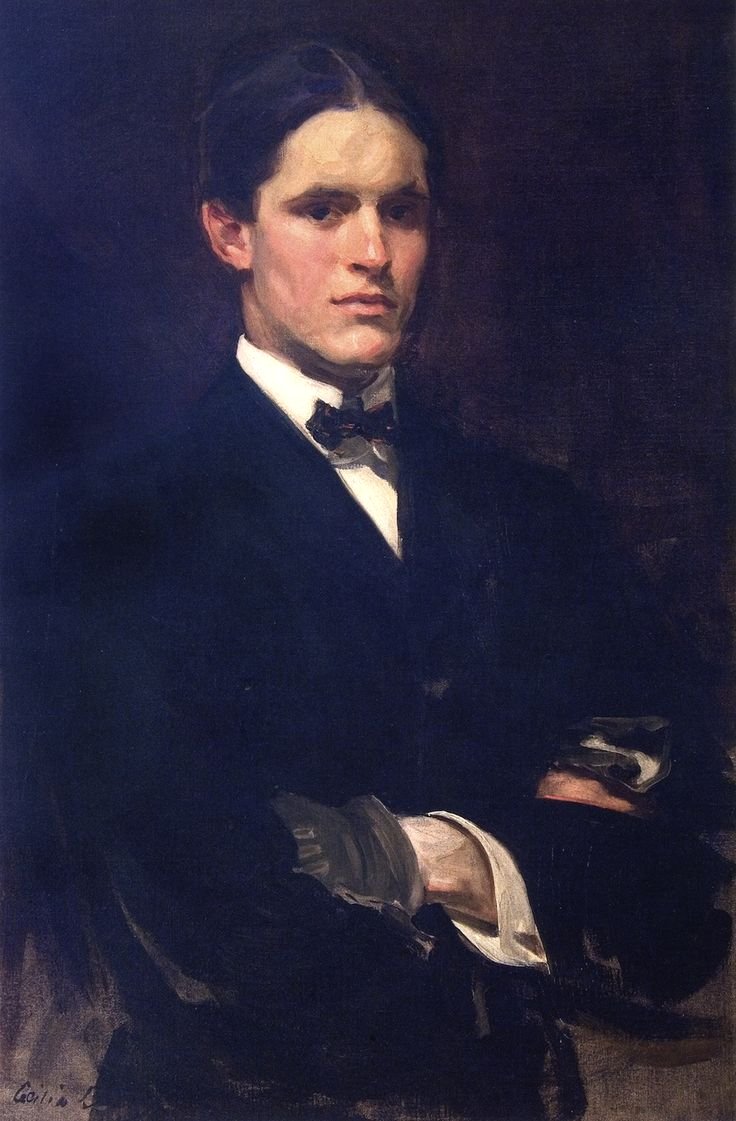

Thornton Oakley was an American artist and illustrator

With all the pressure of work, Cecilia decided that she needed a sanctuary away from her hectic city life. In her biography, she wrote:

“…I began to dream of a change, of’ a pied-a-terre even then — of a shift of the year’s divisions — for work, and rest. Why not, I thought, have the summer for my working time, and take my rest in a short winter period? I had never looked on painting as toil, but I had sometimes felt that the city winter contained too much of everything, and that the summer, if considered as a holiday, was boring in being desœuvre [at a loose end]. Why not have long, unhurried bouts of painting, when off hours would be spent in delicious air — morning and evenings of thrilling loveliness — a long, long summer…”

Cecilia Beaux’s home at Eastern Point, Gloucester, Mass.

Photograph, ca., 1920, by T. E. Morr.

Cecilia decided to rent a place in East Gloucester on Cape Ann in Essex County, Massachusetts. She, along with her Aunt Eliza, Uncle Will, and other relatives first visited the idyllic New England fishing village in July 1887, staying at the Fairview Inn and returned there on a regular basis. In 1903, she decided not to stay at the inn but instead rented a cottage on Eastern Point for the summer. She used to refer to it as the Rock of Calif and whilst she spent the summers there her companion on her first Parisian trip, her cousin, May Whitlock, acted as her housekeeper, and would do so for almost forty years. Whilst at the cottage Cecilia looked for some land where she could build her own house. She finally found the perfect spot, a thickly wooded space on the harbour side of the road, part-way between the lighthouse and the town of Gloucester. She then commissioned the building of a house and studio on the plot of land and was finally able to move into her new house on August 7th, 1906. She named her house Green Alley.

In 1910, her beloved Uncle Willie died. She was devastated by the loss, as William Biddle was the foremost male in her early life after her father left the family home after the death of his wife. William Biddle was just fifty-five years of age when he died.

With the backing of the Smithsonian Institution in 1919, the National Art Committee devised, and were overseers of a project by which American artists would paint the portraits of prominent World War I leaders from America and the allied nations. The National Art Committee selected Cecilia as one of eight painters commissioned to execute portraits of the war heroes. The committee set aside $25,000 for each artist to paint three portraits. Cecilia’s task was to paint the portraits of Cardinal Désiré-Joseph Mercier, the Belgian Cardinal who was renowned for his staunch resistance to the German occupation of his country during the Great War. She was also to paint a portrait of Admiral Lord David Beatty, who led the 1st Battlecruiser Squadron during the First World War and Georges Benjamin Clemenceau, who was a French politician, physician, and journalist and who was Prime Minister of France during the First World War.

Cecilia Beaux continued with her regular visits to Europe accompanied by various companions. One such trip in the summer of 1924, with a young Boston artist, Aimée Lamb, ended disastrously when Cecilia, who was sixty-nine-years-old at the time, whilst out walking in Paris along the rue St. Honoré, caught her heel on the pavement, fell and broke her hip. The accident occurred on June 30th and after ten weeks in a clinic she still was not allowed to return home until November. The terrible accident was a devastating blow to Cecilia, as it crippled her for the rest of her life and necessitated her to wear a heavy steel brace and walk with a crutch. It badly affected how she was able to paint and her output dwindled.

Cecilia Beaux received numerous awards and accolades for her work which was exhibited many times in many countries. She died of coronary thrombosis at her beloved home, Green Alley, on September 17th, 1942. She was aged eighty-seven. Following her cremation in Boston, her ashes were buried in the West Laurel Hill Cemetery in Bala-Cynwyd, Pennsylvania.

This is my seventh and final blog looking at the life of this amazing artist. So much is missing from what I have written. So many of her paintings have not been shown and yet maybe it will tempt you to read her autobiography (Background with Figures) or read the many excellent essays written about Cecilia Beaux by Tara Leigh Tappert.

Most of the information for the blogs featuring Cecilia Beaux came from two books:

Background with Figures, the autobiography of Cecilia Beaux

Family Portrait by Catherine Drinker Bowen

and the e-book:

Out of the Background: Cecilia Beaux and the Art of Portraiture by Tara Leigh Tappert.

Extracts from letters to and from Cecilia Beaux came from The Beaux Papers held at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art

Information also came from the blog, American Girls Art Club In Paris. . . and Beyond, featuring Cecilia Beaux was also very informative and is a great blog, well worth visiting on a regular basis.:

https://americangirlsartclubinparis.com/

Photographs came from an article I found entitled The Only Miss Beaux, Photographs of Cecilia Beaux and her Circle by Cheryl Leibold of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

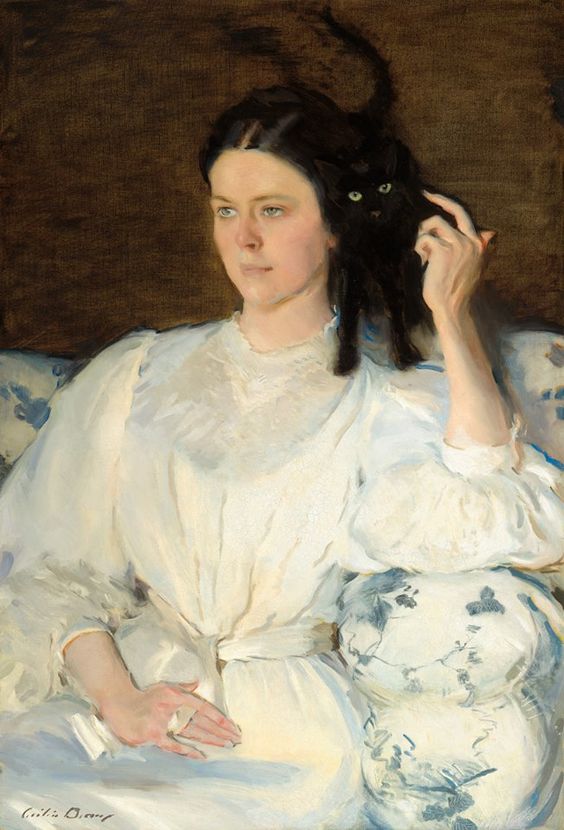

The haunting facial expression of the sitter with her piercing stare makes for a beautiful study.

The haunting facial expression of the sitter with her piercing stare makes for a beautiful study.