After yesterdays disturbing painting I thought I would choose a more romantic offering for My Daily Art Display today. Antoine Watteau, born in Valenciennes in 1684, was the greatest French painter of his era. He was the second son of a well-to-do roof tiler and unlike the early life of so many artists I have studied, his parents encouraged his love of painting but at the age of 18, his family stopped paying for his artistic apprenticeship in his home town and he was allowed to move to Paris to further his artistic schooling and earn a living. He soon found work with local art dealers copying famous paintings.

Whilst in Paris he met the stage-set and costume designer Claude Gillot who based his art work on themes from the Italian Commedia dell’arte, a form of theatre that began in Italy in the mid-16th century characterized by masked “types”, the advent of the actress and improvised performances based on sketches or scenarios. This type of theatre had been banned in France at the end of the seventeenth century when they had ridiculed King Louis XIV’s wife in a parody. On the king’s death in 1715, this kind of theatre came back into fashion.

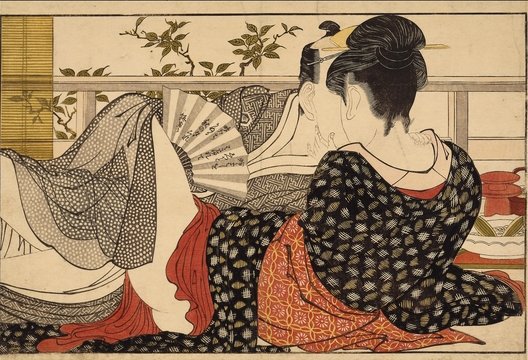

At the age of twenty five he won second place in the Royal Academy competition for the Prix de Rome. Around this time Watteau concentrated a lot of his art depicting military subjects and landscapes. In 1712, with his presentation piece, Les Jaloux (The Jealous), he became an associate member of the Academy. Watteau formed a friendship with the wealthy banker and art collector Pierre Crozat whom he stayed with, in his country estate in Montmorency. It was here that Watteau saw the banker’s magnificent collection of art works from some of the great Masters such as Titian and Veronese and the fêtes galantes themes of some of the paintings were to be an inspiration to the young Watteau. Fêtes galantes is a French term referring to some of the celebrated pursuits of the idle, rich aristocrats in the 18th century—from 1715 until the 1770s. After the death of Louis XIV in 1715, the aristocrats of the French court abandoned the grandeur of Versailles for the more intimate townhouses of Paris where, elegantly attired, they could play and flirt and put on scenes from the Italian commedia dell’arte. The term translates from French literally as “gallant party”. Watteau painted Musical Party which could well have been a depiction of his banker friend Crozat and his entourage enjoying themselves in the park at Montmorency. In 1717 at the age of thirty-three Watteau became a full member of the Academy with his diploma piece Pilgrimage leaving for the Island of Cythera, which is My Daily Art Display offering for today. The board of the Academy found it difficult to categorise the style of his painting and officially termed it as a fête galante and Watteau as a painter of fête galantes, which was to become an important new painting genre. This painting, an allegory of courtship and falling in love, now hangs in the Louvre.

A later variant of it ican be found n Friedrich II’s collection at Schloss Charlottenburg, Berlin. In this latter painting, Watteau has added the masts of the boat and a statue of the goddess of Venus in the right foreground.

Cythera, now known as Kithira, is a mountainous island off the Peloponnesus and was said to be the birthplace of Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love, who was also known as Cytherea (Lady of Cythera) and is the location of her cult and shrine. People who made a pilgrimage to the “island of love” did so filled with eager anticipation. Watteau’s island is an island of love and his brightly coloured landscape add to the enchantment of the scene. Cupids can be seen flying over the boat.

In the painting the scene is set in which lovers are shown on a luscious and densely vegetated island. It is a dreamy vision. Couples are dressed in their silken finery, which we can almost hear rustling as they move about.

One couple is seated and seems to be unaware of their friend’s departure, completely engrossed in what was probably a flirtatious conversation. If we look at the couple in the middle we can see that the gentleman is helping the lady to stand whilst the man from the couple on the left has his arm around his lover’s waist urging her forward as she looks back at her friends, maybe encouraging them to hasten.

There is some debate amongst art historians as to whether the title of the painting has the word “for” in it. In other words are the people we see in the pictures “leaving for Cythera” or “leaving Cythera”. The majority favour their leaving of the island of love. The answer must lie in the people depicted in the painting and their expressions. Are they full of joyful anticipation at heading for the island or somewhat despondent at leaving this paradise of love and happiness?

The question still remains, so I will leave you to look and see what you think.

Auguste Rodin said of the painting in the Louvre:

“…What you first notice at the front of the picture is a group composed of a young maiden and her admirer. The man is wearing a cape embroidered with a pierced heart, a gracious symbol of the voyage that he wishes to embark upon. Her indifference to his entreaties is perhaps feigned. The pilgrim’s staff and the breviary of love are still lying on the ground. To the left of this group is another couple. The maiden is accepting the hand of her lover, who is helping her to stand. A little further is the third scene. The lover puts his arm around his beloved’s waist to encourage her to accompany him. Now the lovers are going down to the shore, laughing as they head towards the ship; the men no longer need to beseech the maidens, who cling to their arms. Finally the pilgrims help their beloved on board the little ship, which is decked with blossom and fluttering pennons of red silk as it gently rocks like a golden dream upon the waves. The oarsmen are leaning on their oars, ready to row away. And already, little cupids, borne by zephyrs, fly overhead to guide the travellers towards the azure isle which lies on the horizon…”