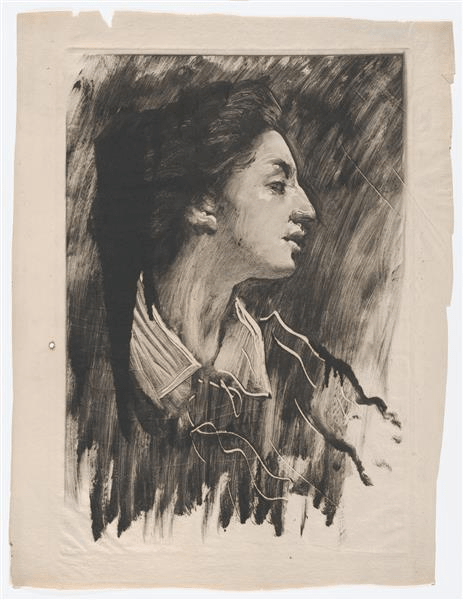

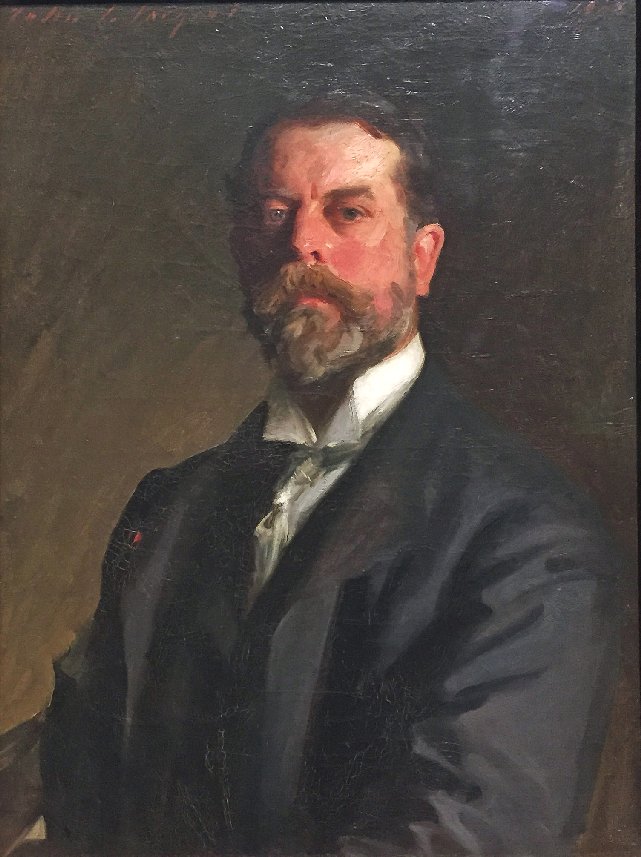

Wilhelmina Douglas Hawley, Self Portrait (1897)

The artist I am featuring today is the American painter and watercolourist Wilhelmina Douglas Hawley. She was born on July 13th 1860 in the small coastal town of Perth Amboy, New Jersey. Her father, Peter Radcliffe Hawley was an officer in the coast guard and her mother, Isabella Hawley (née Merritt), a Canadian-born dancer. Wilhelmina’s ancestors were English and Scottish migrants, who moved to the east coast of the United States and Canada in the seventeenth and eighteenth century

Birthplace of Wilhelmina Douglas Hawley, Merritt Peck House, 213 High Street, Perth Amboy, New Jersey

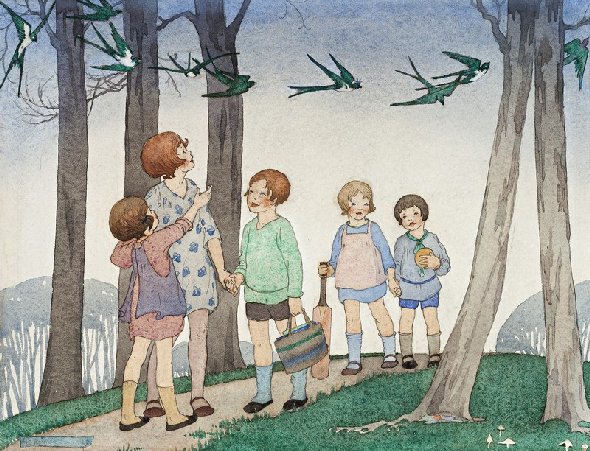

Wilhelmina had three siblings: an older sister Jeanne and two younger brothers William and Alan Ramsey. When Wilhelmina was four-years-old, the family moved to the New York suburb of St Albans, a residential neighbourhood in the southeastern portion of the New York City borough of Queens. Wilhelmina developed two loves during her pre-teen years. One was a love of sketching and painting thanks to two of her unmarried aunts, Florence and Georgina Agnes Merritt and the other was the love of travel once her grandparents took her to Europe when she was just twelve years of age and it was the excitement of visiting so many new places that encouraged her to start writing a journal.

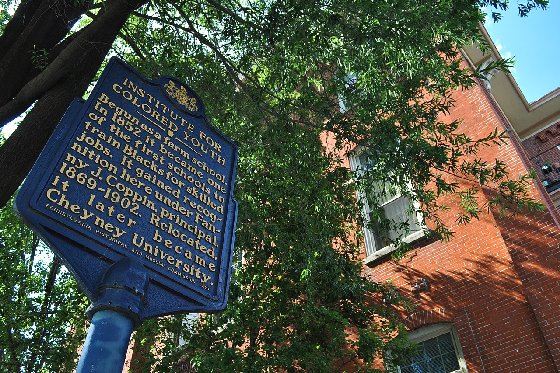

The Cooper Union

Wilhelmina soon developed a love of art and decided to follow the dream of becoming a professional painter. In 1879, at the age of nineteen, she enrolled in the Cooper Union Women’s Art School, one of the New York art academies that is open to women. The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art was established in 1859 and is among the nation’s oldest and most distinguished institutions of higher education. The college, founded by inventor, industrialist and philanthropist, Peter Cooper, offers a world-class education in art, architecture and engineering as well as an outstanding faculty of humanities and social sciences. Cooper took the revolutionary step of opening the school to women as well as men. There was no colour bar at Cooper Union. Cooper demanded only a willingness to learn and a commitment to excellence, and in this he manifestly succeeded.

Two Women near the River Waal by Wilhelmina Douglas Hawley (1894)

Wilhelmina remained at the Cooper Union for a year and then enrolled at the Art Students League where she honed her artistic skills eventually becoming the first woman vice-president of this progressive institution. Her tutors included William Merritt Chase, Julian Alden Weir, Charles Yardley Turner and Kenyon Cox. The popularity of the Art Student League was that it was based in New York and the city attracted many European artists, many of whom Wilhelmina met while living and studying at the Arts League.

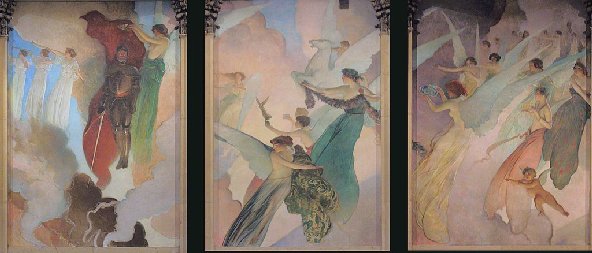

Young Woman in the Meadow by Wilhelmina Douglas Hawley

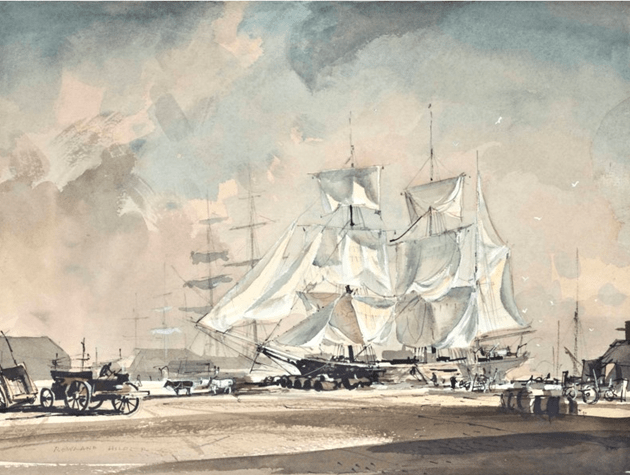

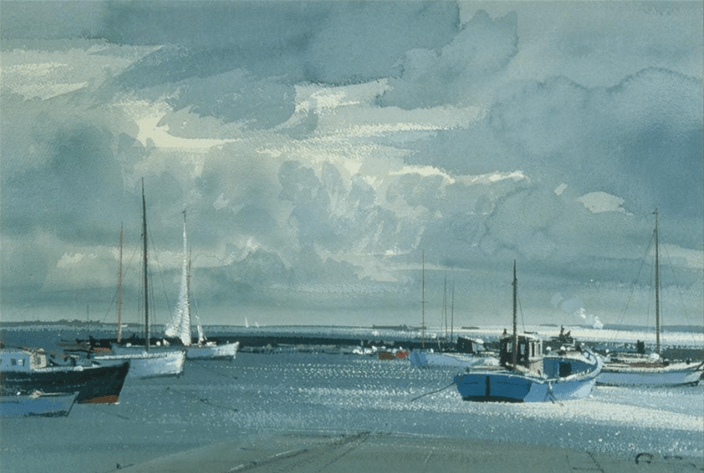

To escape the cold climate of New York, Wilhelmina spent the winter of 1891/2 on the island of Bermuda where she fell in and out of love with a mysterious Englishman whom she had agreed to marry. Fortunately, she realised the error of her judgement and the two split up. Once again, like so many American artists of the time, who succumbed to the magnetism of Paris, Wilhelmina was drawn towards the French capital to continue with her artistic tuition. On June 18th 1892, just a month before her thirty-second birthday, Wilhelmina once more, set sail for Europe on the Holland-America steamer Veendam. During her Atlantic voyage, Wilhelmina was accompanied by the Dutch-American artist John Vanderpoel and his wife Jessie Elizabeth Humphreys. Vanderpoel. He was a well-known artist and taught at the Art Institute of Chicago where one of his tudents was Georgia O’Keeffe, and it was he who most likely suggested to Wilhelmina that she should spend the summer months at the charming village of Rijsoord near Dordrecht in the Netherlands, where he had founded an artists’ colony in 1886.

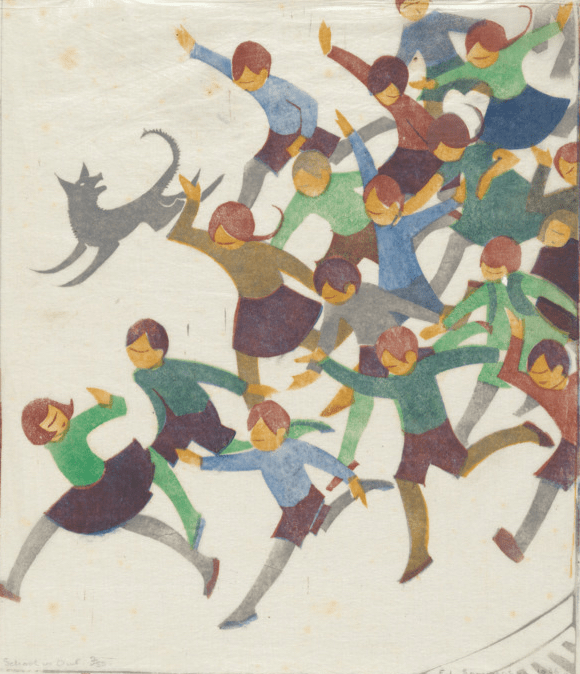

Interior with Mother, two Children and Cat by Wilhelmina Douglas Hawley

On arriving in Paris Wilhelmina registered at the Académie Julian, one of only two art academies in the city to which women and foreign students were admitted. Having arrived in the Summer, all the Academies were closed for the summer break and would not re-open until the September. Wilhelmina used the time to travel throughout Belgium and the Netherlands and on 4 July 1892 she made her first visit to the Dutch flax village and artists’ colony at Rijsoord, where various foreign artists and art students had been living and working since 1888 especially during the summer months. In 1893, Wilhelmina achieved her first artistic successes at the French Academy where she was awarded a prize for best composition. Also for the first time, one of Wilhelmina’s paintings was selected for the Paris Salon that year, and success came from across the Atlantic when her painting, Holland Peasant Girl was shown in New York at an exhibition of the National Academy of Design

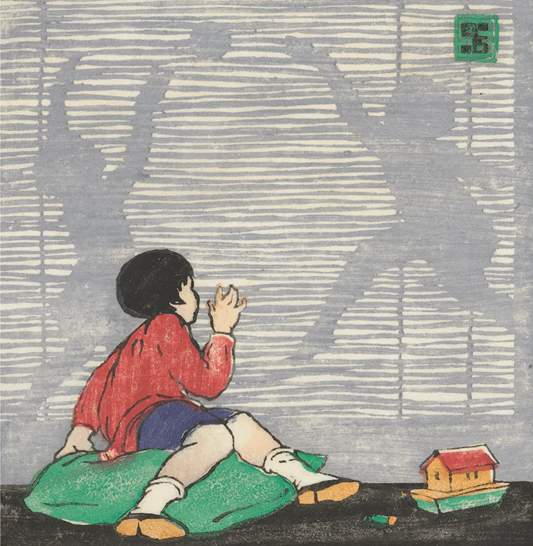

Girl Knitting in a Field by Wilhelmina Douglas Hawley

In 1893, Wilhelmina was appointed as an art teacher at Academy Colarossi and it was around this time that she met English-born Canadian art student, Laura Muntz A friendship between the two women sprung up and Laura moved in with Wilhelmina at her studio at No. 111 Rue Notre-Dame-des -Champs. Close to the Palais de Luxembourg. Directly across from their studio was the studio of American artist, James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Both Laura and Wilhelmina were regular visitor to Whistler’s studio, and he to theirs.

Laura Muntz Lyall.

Laura Munz, who was born in 1860 in Radford, Warwickshire, England, was the same age as Wilhelmina and is recognised as one of the most talented painters of her time. She was an impressionist painter, best known for her depiction of mothers and children. When she was a small child, she emigrated with her family to Canada, where grew up on a farm in the Muskoka District of Ontario.

A Daffodil by Laura Munz Lyall (1910)

In 1882, Laura began to take classes at the Ontario School of Art in Toronto. She also studied briefly at the South Kensington School of Art in 1887, then returned to Canada to continue her studies at the Ontario School. She came to Paris in 1891 and before she met Wilhelmina had been living alone and earning money by teaching and administrative work. She was the first Canadian to receive the distinguished “Honourable Mention” at the Paris Salon exhibition in 1895.

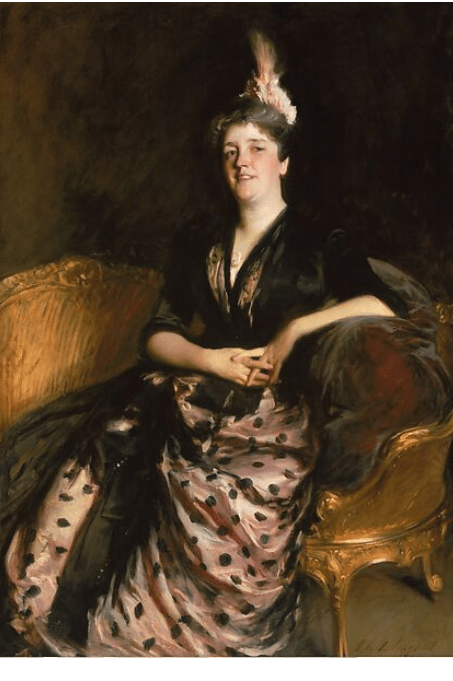

Portrait of Wilhelmina Douglas Hawley by Laura Munz (1897)

In 1896 Laura returned to Canada for a short spell to help look after an ailing relative. She returned to Paris and the Academy Colarossi and was promoted to the post of massiere (Studio head) at the Académie Colarossi. In 1898 she returned to Canada in 1898 and set up a studio in Toronto to teach and paint. In 1906, she moved to Montreal to continue her career and built up a large clientele that regarded her as the premier Canadian portraitist of children. Following the death of her sister in 1915, she returned to Toronto and married her brother-in-law Charles W.B. Lyall and cared for his children of her sister’s marriage, eleven in all, but many had left home by then. She set up a studio in the attic of their home, and started signing her works with her married name. Laura Munz Lyall died in Toronto in 1930, aged 70.

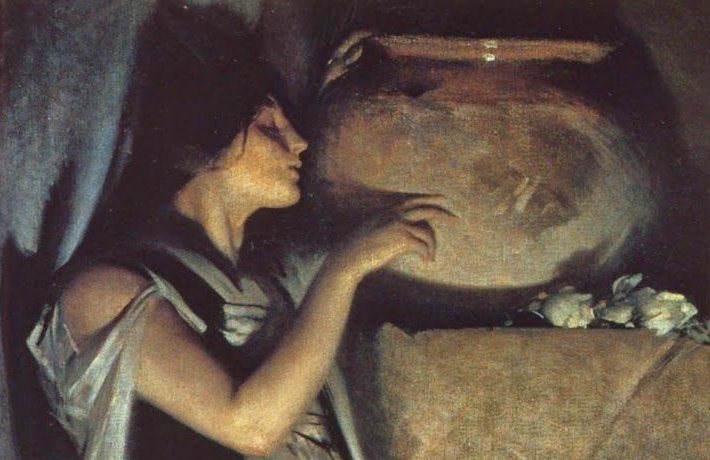

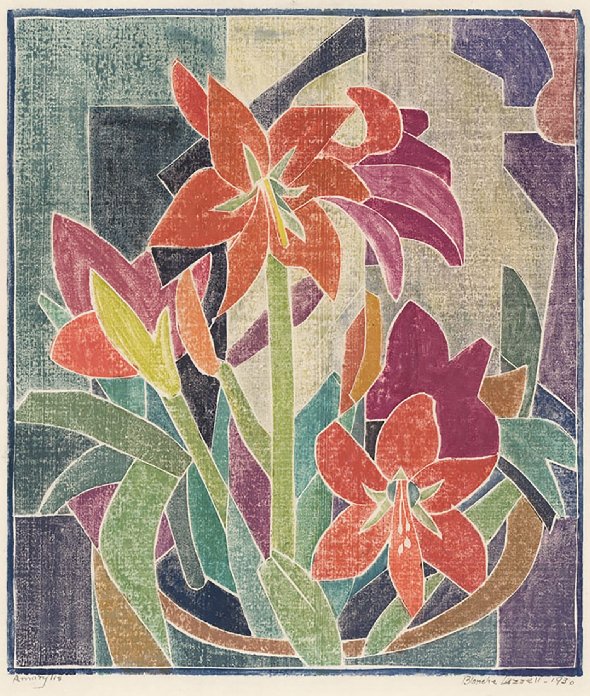

Rose by Wilhelmina Douglas Hawley (1895)

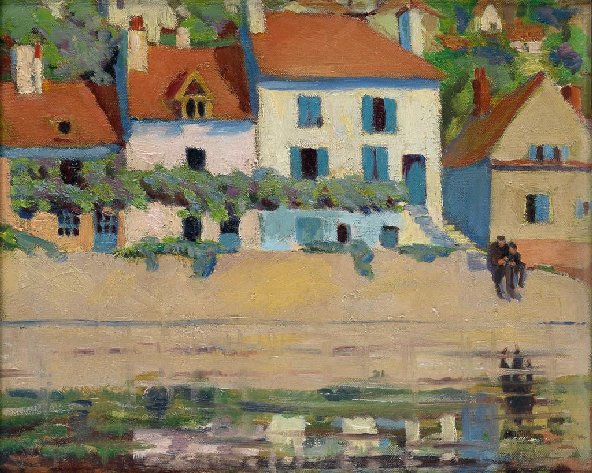

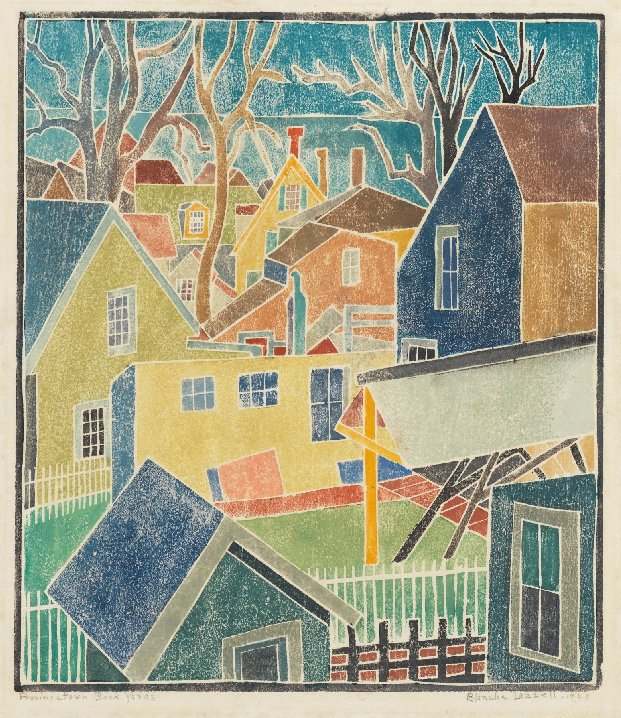

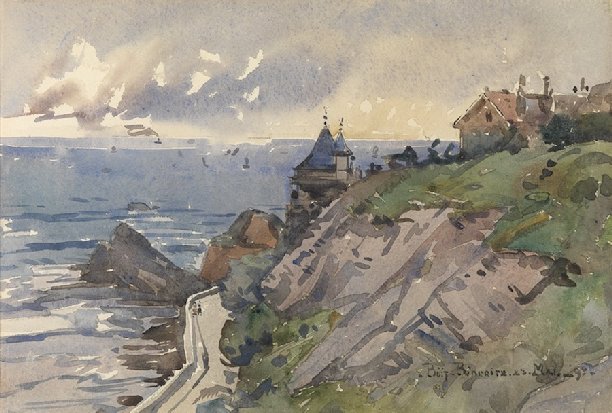

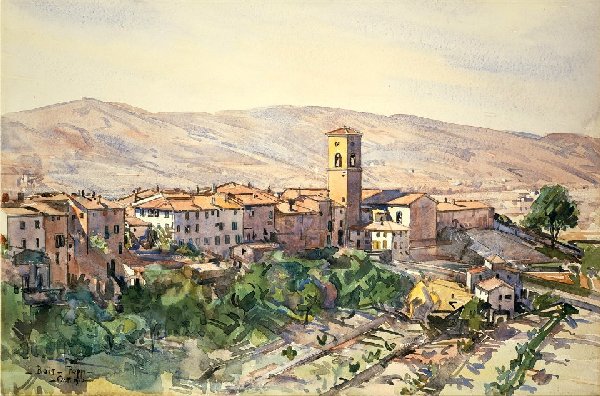

Wilhelmina and Laura spent part of the summers in the French countryside as well as the artists’ colony of Rijsoord in the southern Netherlands. She would often take her international students of the Académie Colarossi with her on these painting trips. It was here that Wilhelmina captured the villagers in oils and watercolours. The village of Rijsoord was well situated for passing travellers on the Rijksstraatweg (State Highway), an important European road that connected Paris to The Hague.

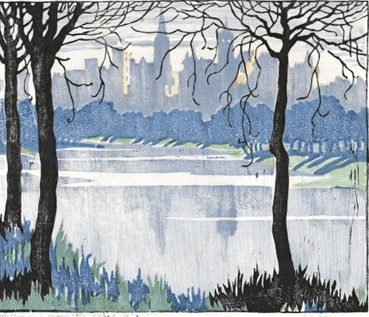

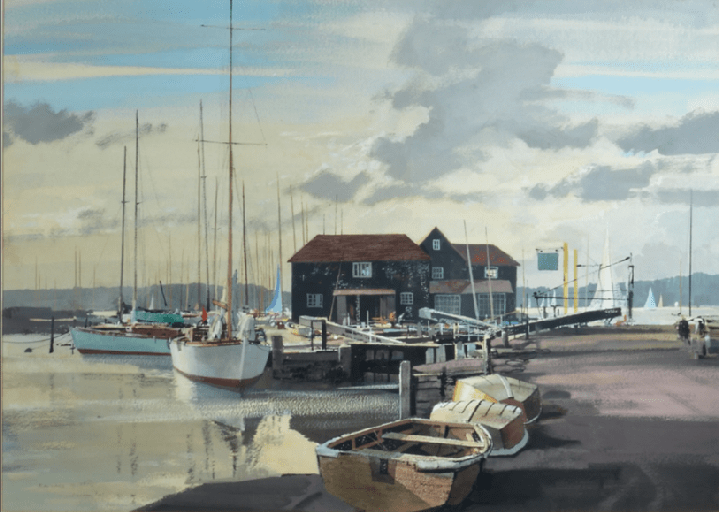

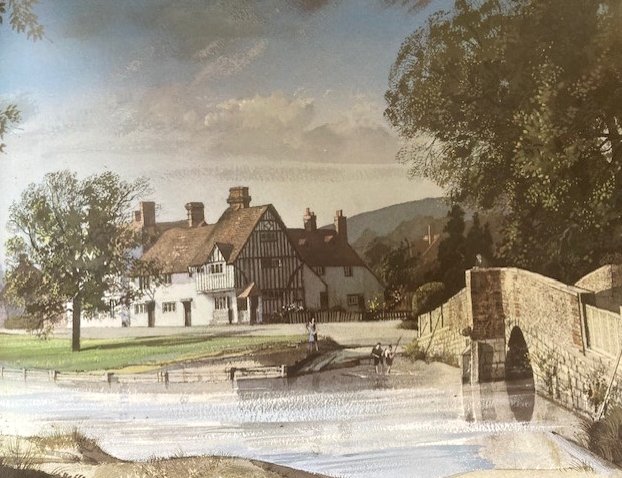

The bridge over the River Waal at Rijsoord, with Hotel Warendorp on the right

An inn was constructed on the spot near the river Waal where the eighteenth-century tollhouse had stood. The building is still standing and for several years had housed the restaurant Hermitage. When Wilhelmina first visited Rijsoord, the inn was called Hotel Warendorp. Hotel Warendorp functioned as the headquarters of the summer academy. The ground floor of the building comprised a livingroom, diningroom and a room for drinking coffee. Most of the guestrooms were also on the ground floor. On the floor above it, the large space under the roof was used as an artists studio, where the artists would hang their most recent paintings and watercolors for discussion. On rainy days, when it was impossible to work en plein air, the artists would actually work in the studio. Wilhelmina’s great granddaughter, Alexandra van Dongen, wrote about how her great grandmother met her husband in her blog: For Two Years, or Perhaps Forever”; Wilhelmina Douglas Hawley and the Artists’ Colony in Rijsoord. The tale is an instalment in a monthly series of blogs telling stories about the rich history shared by the American and the Dutch peoples. She wrote:

“…In 1899, Wilhelmina apparently first encountered the 31-year-old Rijsoord farmer Bastiaan de Koning (1868-1954). They most likely met during a boat trip on the river Waal, as the story goes, as local villagers including De Koning, regularly rowed the artists to their outdoor painting locations. In the summer of 1900 Wilhelmina returned to Rijsoord again and announced her engagement to Bastiaan. They married a year later on December 5, 1901. Another three years later, when Wilhelmina was 44 years old, she gave birth to a daughter, my grandmother, Georgina Florence de Koning (1904-1973), named after Wilhelmina’s aunts. By that time, Wilhelmina had been active in the art world for twenty-five years. Family life did not prevent her from traveling abroad, visit exhibitions or meet her friends in Paris and New York. In 1915, her family in Rijsoord engaged a young housekeeper, Geertrui van Nielen (1895-1981), who became an important supporter in her life. Trui, or Troy, as she was called by Wilhelmina, took care of household matters and looked after Georgy, as Wilhelmina’s daughter was called, when her mother was traveling abroad …”

Wilhelmina continued to live with her husband and daughter in Rijsoord. Years later she enjoyed the summer holiday visits from her daughter, Georgy, her husband, Hans van Dongen and their six children. On February 18th, 1958, Wilhelmina Douglas Hawley passed away at home at the age of 97.

The information I used for this blog came from a number of excellent websites, all of which are worth visiting. They are:

The Society of the Hawley Family

For Two Years, or Perhaps Forever”; Wilhelmina Douglas Hawley and the Artists’ Colony in Rijsoord

Schildersdorp Rijsoord 1886-1914

Finally, may I wish you all a Merry Christmas and hope that peace may return to us all.