Nichiren’s journey continues……………………………

The Mantram “Namumyohorengekyo” Appears to Nichiren in the Waves near Sumida on the Way to Exile on Sado Island. One of the ten Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s Sketches of the Life of the Great Priest series.

Nichiren continued his journey into forced exile on Sado Island with a sea voyage from the mainland to the island. During the sea voyage across the Sea of Japan his boat is hit by a storm, said to have been conjured up by Susanoo-no-Mikoto, a kami associated with the sea and storms, which was likely to capsize the boat.

Nichiren casts a spell the first line of the Lotus Sutra, “Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō (Devotion to the Mystic Law of the Lotus Sutra as seen written on the waves.

Nichiren’s crew were terrified fearing death but Nichiren remained steadfast and cast a spell on the raging sea by reciting the first line of the Lotus Sutra, “Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō (Devotion to the Mystic Law of the Lotus Sutra) and these words appear on the waves. The words are a pledge, an expression of resolve, to embrace and demonstrate our Buddha nature. It is a promise to ourselves that one will never acquiesce in the face of problems and that one will overcome sorrow and pain. The sea immediately became calm. You will notice that depiction of the curling wave resembles Hokusai’s great 1831 print entitled The Great Wave off Kanagawa.

It was a similar wave depictions Utagawa Kuniyoshi used in his 1847 series entitled Tametomo s ten heroic deeds as seen above.

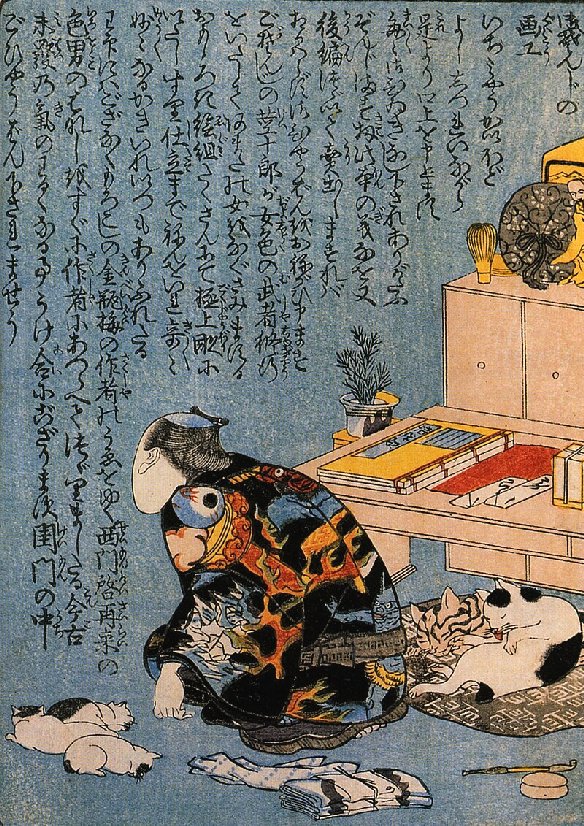

In the Snow at Tsukahara, Sado Island. One of the ten Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s Sketches of the Life of the Great Priest series.

The sixth print in the series is looked upon as the greatest example of Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s work and depicts the exiled monk, Nichiren, in his red robes, climbing, by himself, up a hill covered in snow. He had been earlier exiled by the regent Hojo Tokimune for his outspoken views on mainstream Buddhism and taken to Sado Island where he was abandoned in a cemetery with only a makeshift shelter to protect him from the elements in the midst of a harsh winter. An icy wind whips through his loose garments. He struggles to ascend, and his bare legs are ankle-deep in the snow. Utagawa uses a snowstorm to represent the cold reality the exile is facing. Behind him and to his right the houses in the village are visible.

Bunpô sansui gafu (Album of Landscapes by Bunpô) 1824.

It is believed that Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s landscape was influenced by the Japanese artist Kawamura Bunpō, and was based on a design from his book, Bunpō sansui gafu (A Book of Drawings of Landscapes by Bunpō). The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York which has this print in its collection refers to it as a “masterpiece of ukiyo-e printmaking prints”. They describe it as a particular masterpiece of ukiyo-e printmaking as it creates a perfect resonance between pictorial and emotional presentation. The severe snowstorm symbolizes the hardships Nichiren underwent during his exile. The monk demonstrates his strength of spirit by persevering in his uphill struggle.

Claude Monet was an avid collector of Japanese prints and it is thought that some of his snowy winter landscapes were influenced by Japanese woodcut prints. When he died, Monet left behind 231 Japanese prints decorating his house at Giverny, one of which was Utagawa Kuniyoshi’sprint, In the Snow at Tsukahara, Sado Island.

The Rock Settling a Religious Dispute at Ōmuro Mountain on the Twenty-eighth Day of the Fifth Month of 1274. One of the ten Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s Sketches of the Life of the Great Priest series.

The setting for the seventh print of the series is in Komuroyama. We see Nichiren has managed to suspend in the air a large rock which has been hurled towards him by a member of the Yamabushi, a Japanese mountain ascetic hermit. This action by Nichiren was achieved by the sheer will of his spiritual power. A different versions of the story exists in which it is said that a member of a competing Buddhist school invited Nichiren to a contest to see who had the greater religious power to control the levitation of a rock. According to this legend, the man was able to lift the rock but Nichiren prevented him from lowering it. Upon losing the contest, the story goes, the man left his sect and became a Nichiren’s follower.

Nichiren Praying for the Repose of the Soul of the Cormorant Fisher at the Isawa River in Kai Province. One of the ten Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s Sketches of the Life of the Great Priest series.

In the eighth print of the series, we see Nichiren in his red robes, seated in prayer, sitting atop a cliff overlooking a river. Below is a small fishing craft used by fishermen who use trained cormorants to catch the fish. Two men sit in the boat, their hands also clasped in prayer. Nichiren had an affinity towards fishermen as his father was once one. However, at this time, a number of Buddhist sects showed prejudice towards fishermen as they killed (fish) for their own consumption. The story of Nichiren and the cormorant fisherman was the basis of the kabuki play Nichiren shônin minori no umi (Nichiren and the waters of Dharma), and Kuniyoshi had also featured it in a series of 10 landscape prints published around 1831.

The Priest Nichiren praying for the restless spirit of the Cormorant Fisherman at the Isawa river by Yamamoto (Yamamoto Shinji)

The woodcut print artist Tsukioka Yoshitoshi a few years later returned to the theme of Nichiren and the cormorant fishers with his own work, a triptych, entitled The Priest Nichiren praying for the restless spirit of the cormorant fisherman at the Isawa River. On the left panel is the ghost of the fisherman Kansaku, who had died as a result of fishing in a sacred area, and in 1274 appeared to Nichiren in a dream and begged him to save his lost soul. On waking, the priest found himself on the bank of the Isawa river in the Province of Kai, and there he prayed for Kansaku’s soul. Kansaku’s ghost is attended by several of the cormorants that he used to catch fish for him (tight metal collars were placed round the cormorants necks so that they could not swallow the fish before he had collected it).

Nichiren presiding over a crowded service in a temple hall, a dragon emerging in a dark cloud from the inert body of a woman lying prostrate before him. One of the ten Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s Sketches of the Life of the Great Priest series.

The ninth print of the series is a depiction of Nichiren’s 1277 encounter with a dragon. He was at Mount Minobu praying along with many of his supporters at a prayer assembly in the temple. Suddenly a beautiful woman appeared on the floor in front of him and interrupted his prayers.

Nichiren performs an exorcism on the woman in the temple, bringing forth a dragon which frightens the people gathered at the assembly. To calm the assembled people Nichiren holds aloft his Buddhist scriptures demanding that the woman should show her true self at which point she transforms into a shichimen daimyōjin (seven-faced dragon). Following her revealing her true identity, she vanishes.

The Saint’s Efforts Defeat the Mongolian Invasion in 1281. One of the ten Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s Sketches of the Life of the Great Priest series.

The final print in the series focuses on the war between the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty of China and Japan in 1281 when that summer the Mongols invaded Japan. This was the second time the two regimes had clashed. The first time the two nations fought was seven years earlier when the Mongol’s first invasion of Japan occurred in 1274. In the battle, a storm fortuitously aided the Japanese defence, as it helped to sink part of the Mongol fleet. Legend has it that Nichiren predicted the Mongol invasion in his book Risshō Ankoku Ron. It was the fierce storm which put an end to the Mongol invasion and Nichiren was given credit for conjuring up the storm. However, it should be remembered that Nichiren often predicted that Japan would be destroyed for ignoring him and his teachings about the Lotus Sutra. The woodblock print depicts the Japanese soldiers being driven back the Mongol invasion. Mongol ships continue the battle by launching fire stones from catapults towards the shore, but the ships appear to be sinking due to the storm and power of Nichiren’s prayers.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi received a commission in 1831 for this new print series in remembrance of the 550-year anniversary of the death of Nichiren, the founder of Nichiren Buddhism. The finished prints were later used for Nichiren Buddhist religious materials.

Statue of Nichiren Daishonin on the outskirts of Honnoji, in the Teramachi district of Kyoto.

Nichiren was born on 16th of the second month in 1222, which is 6 April in the Gregorian calendar and died outside of present-day Tokyo, on October 13th 1282. According to legend, he died in the presence of fellow disciples after having spent several days lecturing from his sickbed on the Lotus Sutra.

In 1856 Utagawa Kuniyoshi suffered from palsy, which caused him much difficulty in moving his limbs. It is said that his works from this point onward were noticeably weaker in the use of line and overall vitality. He died in his home in Genyadana in 1861 aged 63.