The featured artist in My Daily Art Display today is German and is looked upon, along with the artist I featured in my previous blog, Caspar David Friedrich, as one of the most famous and most successful German artists of the nineteenth century. His name is Adolph Friedrich Erdmann von Menzel.

Menzel was born in 1815 in Breslau, which is now the Polish city known as Wroclau. His father Carl Erdmann Menzel was originally a school headmaster but when young Menzel was just three years of age he gave up his educational career and started up a lithographic printing works. Adolph Menzel first exhibited a drawing in 1827 when he was only twelve years of age and two years later he exhibited eight lithographs, which were printed in his father’s workshop and which featured the history of Breslau. To gain more business opportunities for his printing company, Menzel’s father moved his family and business to Berlin in 1830 where he knew he was likely to receive more commissions. Adolph Menzel became an apprentice in his father’s firm and at the age of seventeen took over the running of the company when his father suddenly died. His mother and siblings now looked upon Adolph as the family breadwinner.

In 1833, aged 18 Menzel enrolled at the Berlin Königliche Akademie der Künste where he met the wallpaper manufacturer, Carl Heinrich Arnold, who would not only become Menzel’s close friend but would furnish him with a large number of commissions. His reputation as an artist and illustrator grew after he had completed a commission for the art dealer and publisher, Louis Sachse, to create a number of lithographs for the German writer, Goethe, for his book Künstlers Erdenwallen. It was not until 1837 that von Menzel started to paint in oils. His speciality subject for his paintings was the life and events surrounding Friedrich the Great and in 1839 he was commissioned to illustrate a book, Geschichte Friedrichs des Großen (History of Friedrich the Great) written by Franz Kugler, a Prussian cultural administrator and art historian. In a three year period 1839 to 1842 Menzel produced over 400 drawings.

It was not until the 1850’s that von Menzel started to travel extensively, visiting Vienna, Prague and Dresden. It was also in 1855 that he made his first visit to Paris where he attended the inaugural Exposition Universelle, the first World Fair to be held in the capital. It was held in the specially built building, Palais de l’Industrie, which overlooked the Champs-Elysées. Whilst there, von Menzel, was able to study not only the industrial exhibits but also the art exhibits on display by French artists such as Gustave Courbet. Eleven years later von Menzel returned to Paris to attend the second Exposition Universelle in 1867 and it was during this stay in the French capital that he visited the Tuileries Gardens which is the subject for today’s painting. That same year he was decorated with the “Cross of the Légion d’honneur by Napoleon III for his service to the arts.

By the 1880’s von Menzel had established his international reputation as an artist and lithographer. In 1884 the Nationalgalerie in Berlin held the first major retrospective of von Menzel’s work to commemorate the 50th anniversary of his career as an artist. In 1890, aged 70, he was given an honorary doctorate from Berlin University. He was bestowed with many other honours. He was made an honorary citizen of both Breslau and Berlin and made a member of both the Royal Academy of London and a member of the Akadémie des Beaux Arts, the Paris Academy. His greatest honour came in 1898 when he became the first artist to be admitted to the Order of the Black Eagle as a Knight, the highest order of chivalry in the Kingdom of Prussia.

Adolph von Menzel died in Berlin in 1905, aged 89.

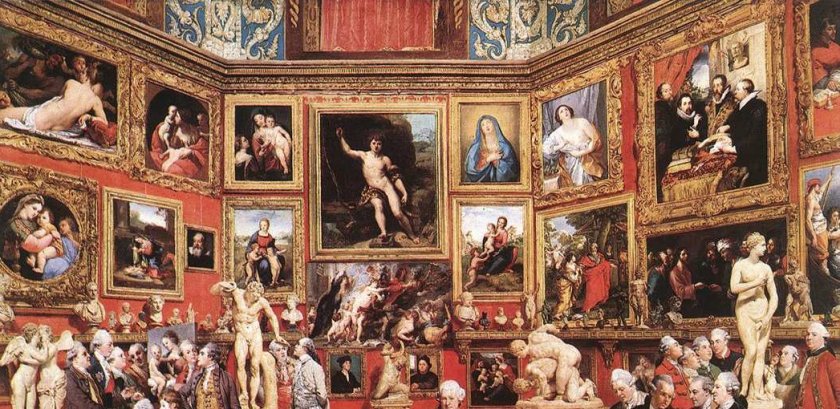

My Daily Art Display featured painting today is entitled Afternoon at the Tuileries Garden by Adolph Menzel. He painted it in 1867 and now hangs in the National Gallery, London. It was following Menzel’s 1867 trip to Paris that he returned to his studio in Berlin with many sketches of the Tuileries Gardens, which lay across from the Louvre. He had become interested in painting scenes set in areas where society people pretentiously paraded and whilst in Paris was fascinated with the bustling social goings-on within the Gardens. The subject matter of his paintings were at this time often depicting bourgeois society and he, because of his fame as an artist, lived the lifestyle of this very grand bourgeois. Menzel’s painting is filled with detail and exudes a great deal of realism.

What I like about the works is that with so much going on in the painting your eyes flick from one group to another and every time you look at it your eyes focus on something different. I like the number of separate vignettes taking place. Let your eye wander up the centre of the painting and observe the little chubby girl being dragged off by the woman in blue. How often have we seen that! Dogs abound, in some cases having territorial disputes whilst the adults try their best to ignore such distractions and have only one thing in mind – to look their best! When the painting was first exhibited Menzel was at pains to tell everybody that it was done from his memories of his recent visit to the French capital.

Was it a work just from memory or was there something else which prompted Menzel to depict such a scene? In my next blog I will give you another possible motivation for Menzel’s depiction of the Tuileries Garden. Notwithstanding what inspired Menzel to paint this lively event, which is buzzing with activity, it is a fascinating work of art. I stood before it the other day and I was mesmerised by what I was looking at and as I said the other day, when talking about Caspar David Friedrich’s Winter Landscape, I was so pleased I had visited Room 41 of the gallery. The next time you visit the National Gallery; don’t forget to pay that particular room a visit. I guarantee you will not be disappointed.