The Portrait Artist

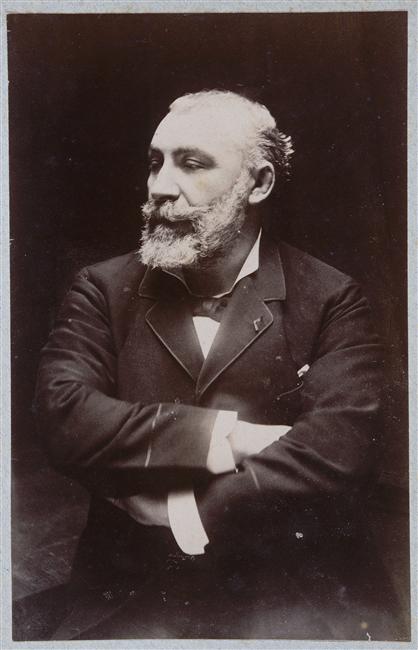

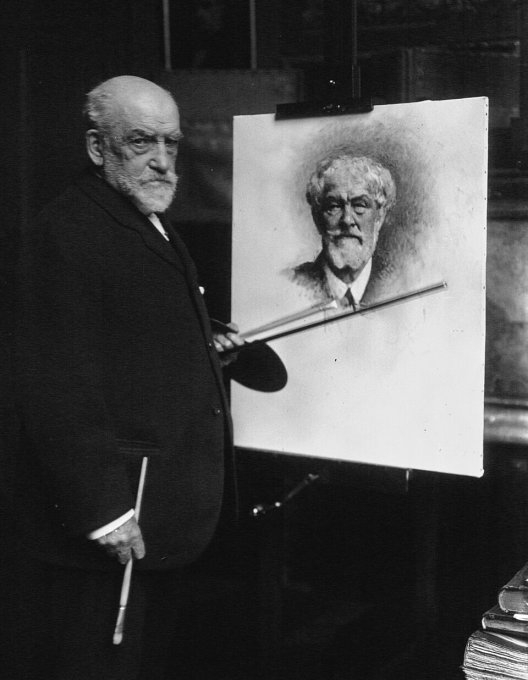

Léon Bonnat painting a portrait of artist, Alfred Roll (1918)

Léon Bonnat was born in Bayonne, France and lived there until he was thirteen years old. Léon’s family then moved to Madrid where his father took on a book shop. Léon’s love of art began to materialise after he went to live in the Spanish capital and, to encourage him, his father would take his son to the Prado. He remembered those museum visits, saying:

“…I was brought up in the cult of Velasquez. I was very young, in Madrid; my father, on bright days such as one only sees in Spain, sometimes took me to the Prado Museum, where we did long stops in Spanish cinemas. I always left them with a feeling of deep admiration for Vélasquez… “.

Italian Woman with Child by Léon Bonnat

In 1853, when Léon was twenty, his father died and the family returned to their French hometown of Bayonne. After studying at the Ecole de Dessin de Bayonne, he went to live in Paris and study at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. In Paris, he was able to view paintings by the great Masters of French and Dutch art and particularly remembers seeing the works of Rembrandt and the influence his works had on him, commenting:

“…What is striking about Rembrandt is the power, the strength and the brilliance. He represents life in all its intensity. We see his characters, we talk with them, he resuscitates and revives an entire era. a marvellous and unique gift of interpretation, he joins the sensitivity, the goodness of a heart which vibrates to all the miseries, to all the joys, to all the emotions of humanity. He does not belong to any school. He has opened the new path which closed behind him…”

Roman Girl at a Fountain by Léon Bonnat (1875)

In 1857 he came second in the Prix de Rome competition and left Paris and spent three years at the Villa Medici. The Villa Medici, now the property of the French State was founded by Ferdinando I de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, and has housed the French Academy in Rome and welcomed winners of the Rome Prize since 1803, so as to promote and represent artistic creation in all its fields.

L’Assomption de Marie by Léon Bonnat (1869)

L’Assomption de Marie in situ in the Church Saint-André à Bayonne (Pyrénées-Atlantiques, Nouvelle-Aquitaine, France)

In 1869 Bonnat was awarded the Medal of Honor of the Salon for his painting L’Assomption.

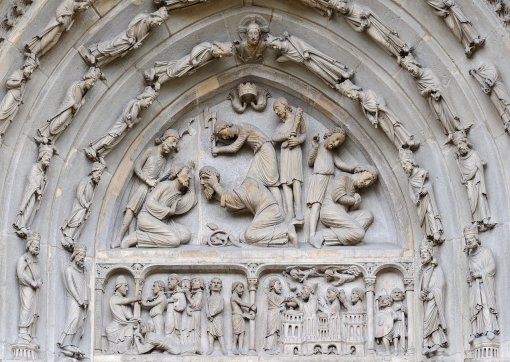

The Martyrdom of Saint Denis by Léon Bonnat (1880)

One of Bonnat’s last religious paintings was his 1880 painting entitled The Martyrdom of Saint Denis. St Denis was a 3rd-century Christian martyr and saint. Denis was Bishop of Paris and through his speeches, made many conversions but he was looked upon by the local Roman priest as a danger and had Denis together with his faithful companions, the priest Rusticus and deacon Eleutherius, executed. The place of the execution, by beheading, was on the highest hill in Paris, which is now known a Montmartre. Denis was said to be against the beheading taking place at this spot and “folklore” has it that after Denis was beheaded, the corpse is said to have picked up his severed head and walked ten kilometres from the top of the hill, and during that entire walk he preached a sermon.

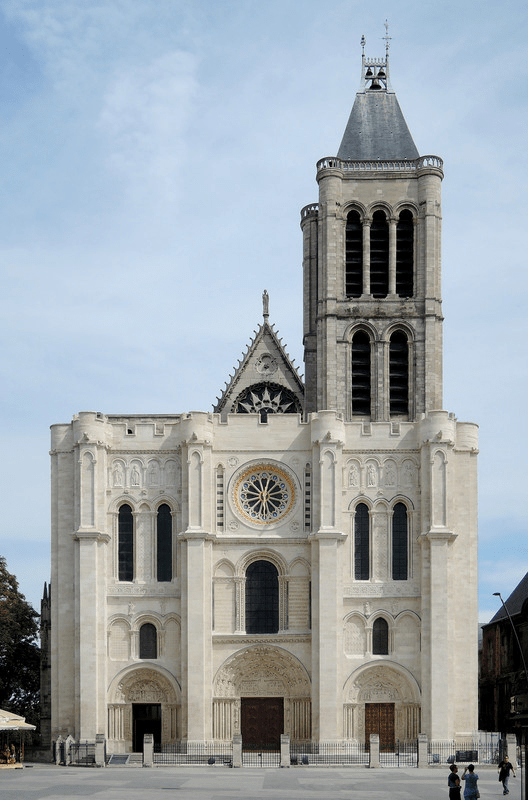

Basilica of St Denis, Paris

Detail of the north portal sculpture; the martyrdom of Saint Denis, Eleuthere and Rustique

Denis finally collapsed at the place where he wanted to be buried, the spot where now stands the Basilica of St Denis and which is also the burial place of the Kings of France. Saint Denis is the patron saint of both France and Paris.

View of Jerusalem by Léon Bonnat

Although, as we will see later, Bonnat was best known for his portraiture and his early historical and religious subjects, but his landscapes and Orientalist depictions are looked upon as among his most intensely personal and beautifully crafted works. Léon Bonnat travelled to the Middle East in 1868 together with a party that included the French painter, Jean-Léon Gérôme, his pupil Paul-Marie Lenoir, the Dutch artist Willem de Farmas de Testas and Gérôme’s brother-in-law Albert Goupil. The journey began in January 1868 at the Egyptian port of Alexandria and by the third of April, the group had arrived at the gates of Jerusalem. Willem de Famars Testas recalled their first glimpse of the walled city:

“…The first glimpse of Jerusalem was gripping, the sun-illuminated city was silhouetted against a violet thundery light, while the outlying land lay under the shadow of clouds…”

Léon Bonnat recorded the impressions and the specifics of their arrival at the gates of Jerusalem in April of that year in one of his may oil on canvas sketches entitled View of Jerusalem.

An Arab Sheik by Léon Bonnart (c.1870)

One of Léon’s works from this period was entitled An Arab Sheik which he completed once back in Paris. It is thought that Bonnat’s depiction emerged from combining multiple resources such as the French model who posed for the seated figure; the saddle we see which Bonnat brought back from his travels and a multitude of sketched notations which he made during his travels in the Middle East. Combining all this data Léon managed to create a painting that appears authentic, and yet, it is stereotypical of what Europeans believed about the Arabic world and its people such as the way the sheik holds his sword depicting his strength and fierceness and enhances how Europeans believed that that cultures in the Middle East and elsewhere were ruled by violence, in contrast to the supposedly more “civilized” societies of Europe and North America.

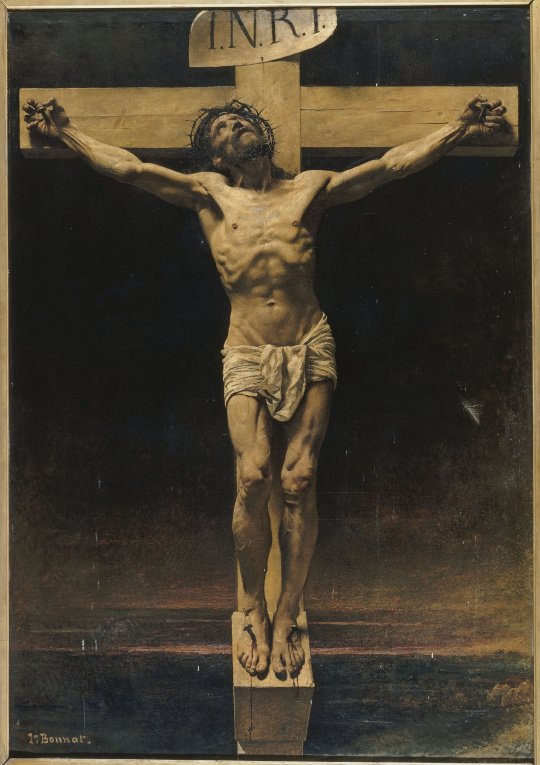

Christ on the Cross by Léon Bonnat(1674)

Bonnat’s haunting work entitled Christ on the Cross was commissioned in 1873 for the courtroom of the Cour d’Assises of the Palais de Justice in Paris. The reasoning behind the commission was that it would embody divine justice in the eyes of the accused and by reminding them of the sufferings of Christ to save the fishermen. The painting was submitted at the 1874 Salon. The painting measures 1.59 meters in width and 2.27 meters in height. Bonnat’s depiction fundamentally renews the traditional representation of Christ on the cross. Christ is shown with a crown of thorns, his body is muscular and pale, and he wears a simple white loincloth. Blood is visible from the nails piercing his hands and feet. The background is dark and sombre. The crucified Christ is characterised in an extremely realistic way, accentuating Christ’s suffering due to the torture he received. Christ on the Cross is one of the best known and best loved crucifixion paintings of the western world. The painting can be viewed at the Petit Palais, Museum of Fine Arts of the City of Paris.

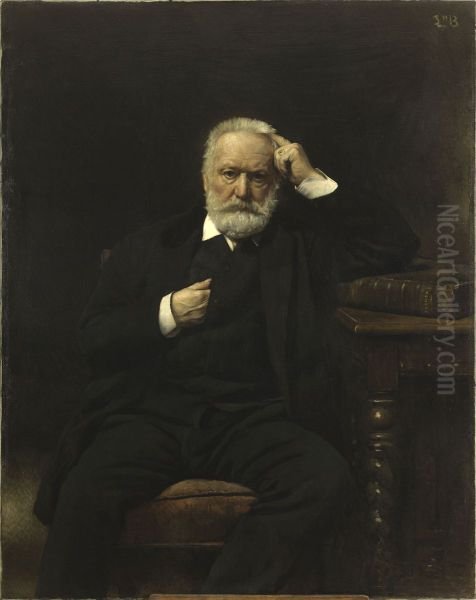

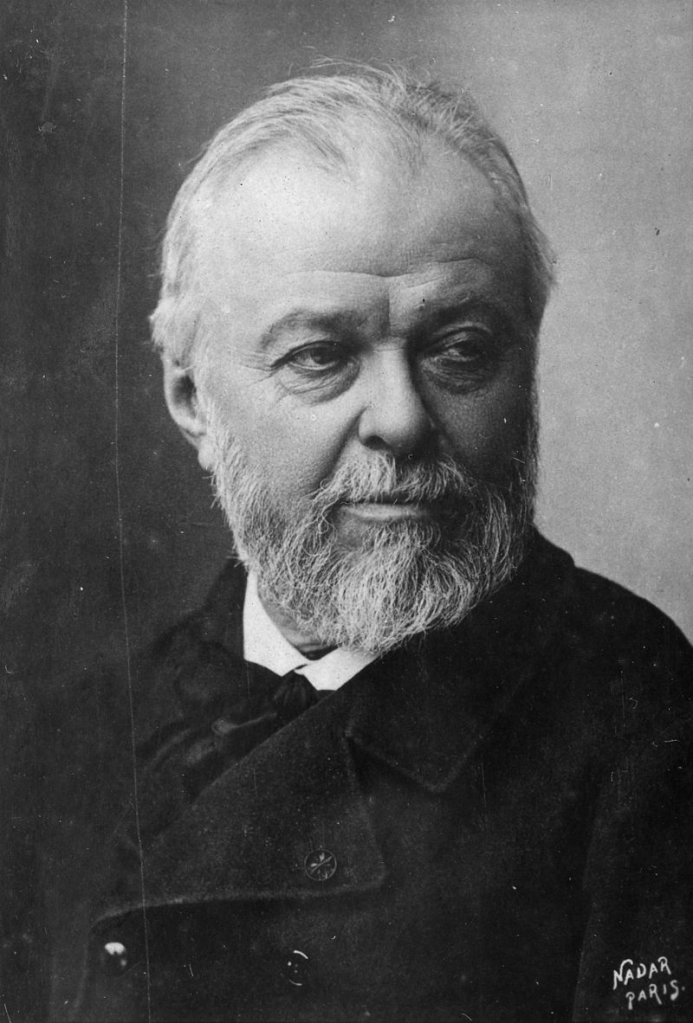

Victor Hugo by Léon Bonnat (1879)

For an artist to survive financially he or she must sell their work. Once back in France, after his three-year stay at Villa Medici in Rome, Léon realised that the sale of his historical and religious paintings had fallen off and he had to look for another painting genre which would attract more buyers. While Bonnat created many religious and historical works, his long-lasting fame rested on his exceptional career as a portrait painter. In an era before photography became the norm, painted portraits were central for chronicling the likenesses of important individuals, and Bonnat became one of the most sought-after portraitists of the French Third Republic and beyond. His sitters included presidents, politicians, writers, scientists, artists, and members of high society.

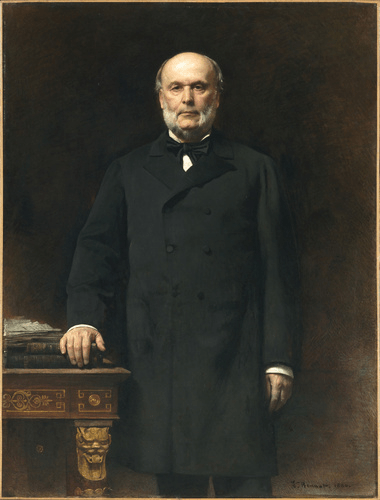

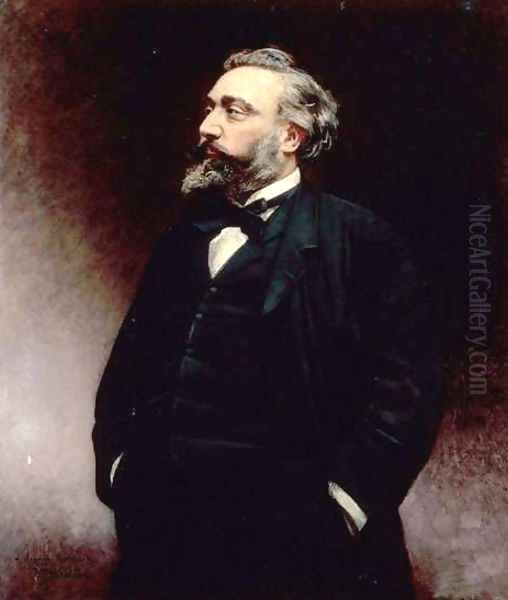

Jules Ferry by Léon Bonnat (1888) Jules François Camille Ferry was a French statesman and republican philosopher. He was one of the leaders of the Moderate Republicans and served as Prime Minister of France from 1880 to 1881 and 1883 to 1885.

Bonnat artistic brilliance as a portrait artist was his extraordinary skill in capturing not just a physical likeness but also the sitter’s charm, personality and social standing. His portraits are typified by their unruffled gravity, psychological perception, and scrupulous attention to every detail, whether it be the texture of fabrics to the detailed features of the face and hands. Bonnat often used dark, neutral backgrounds, which allowed viewers to focus entirely onto the subject, which were often illuminated by a carefully controlled light source, a technique evocative of the Spanish painter, Velázquez.

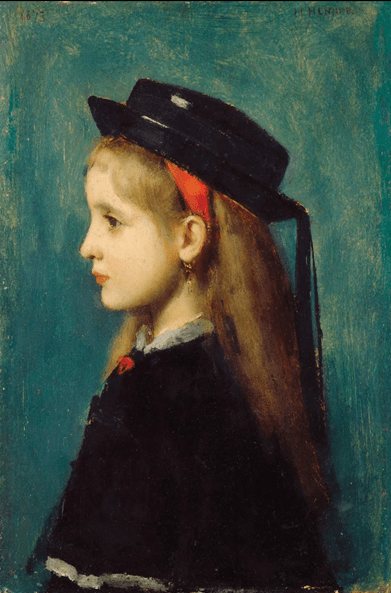

Portrait of Marthe and Therese Galoppe by Léon Bonnat (1889)

Marthe and Therese Galoppe were prominent figures in 19th-century France, known for their social standing and involvement in Parisian society. The painting captures their youthful beauty and grace, reflecting the evolving role of women in society during that time. Bonnat’s portrayal of the Galoppe sisters is significant as it showcases women not just as muses but as individuals with their own identities, challenging traditional views of women in art.

Armand Fallières by Léon Bonnat (1907) French statesman who was President of France from 1906 to 1913.

Among his most famous sitters were famous figures were the statesman Adolphe Thiers, the revered author Victor Hugo, the pioneering scientist Louis Pasteur, fellow painter Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, and French Presidents like Jules Ferry and Armand Fallières. Bonnat’s portraits served not only as personal records but also as official images that helped shape the public perception of these influential individuals. His success in this genre brought him considerable wealth and prestige.

Portrait of Léon Gambetta by Léon Bonnat (1888) Gambetta was a French lawyer and republican politician who proclaimed the French Third Republic in 1870 and played a prominent role in its early government.

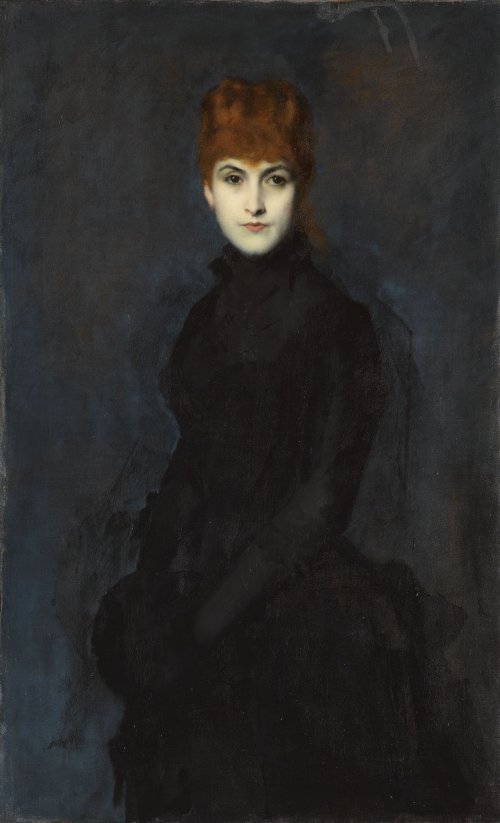

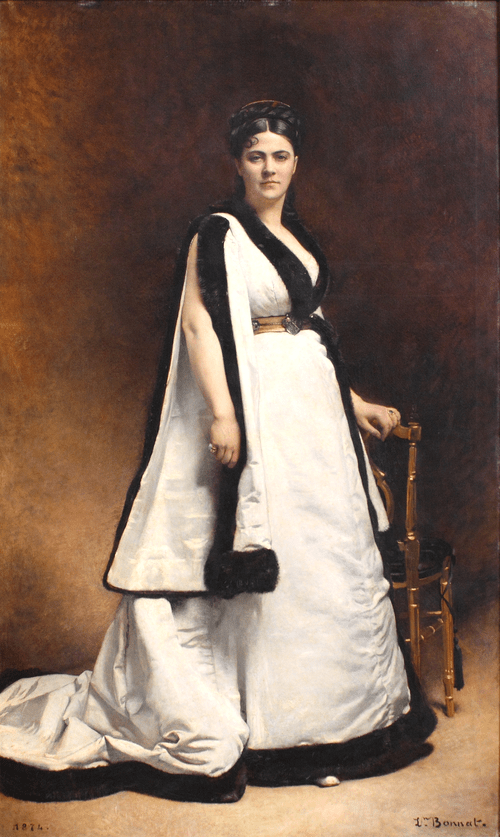

Madame Pasca by Léon Bonnat (1874) Alice Marie Angèle Pasquier was better known by her stage name Madame Pasca, a French stage actress.

Bonnat’s methodology when it came to creating portraits was known to be both thorough and painstaking. He demanded of his sitter numerous meetings so that he could carefully observe them in order to capture subtle gradations of expression and posture and because of this, he was able to achieve prolonged observations which allowed him to realise a high degree of naturalism along with psychological depth. However, Bonnat’s long processes to achieve a finished portrait did not always please the sitters. Although he was minded as to what the sitter wanted in the finished portrait, Bonnat refused to flatter his subject and simply strived for an unvarnished truth, but still conveying the dignity appropriate to the subject’s station in life. His commitment to authenticity along with his undoubted technical mastery in delivering form and texture, achieved the finished product being solid, present, and intensely real.

Portrait of Jules Grévy by Léon Bonnat (1880). Jules Grévy was a French lawyer and politician who served as President of France from 1879 to 1887.

Léon Bonnat who had benefited, following the intervention of the mayor of Bayonne, Jules Labat, when he was granted a municipal scholarship from the city to study the Fine Arts in Madrid and then later in Paris, announced his intention to give his native city the gigantic art collection he had built up. Léon Bonnat’s dedication to art extended well beyond his lifetime through this act of extraordinary generosity. Léon had no direct heirs, and decided to bequeath his extensive personal art collection, along with many of his own works, to his hometown of Bayonne.

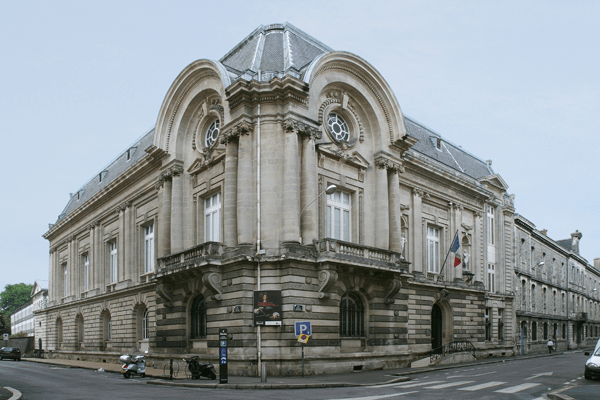

Musée Bonnat-Helleu in Bayonne, France

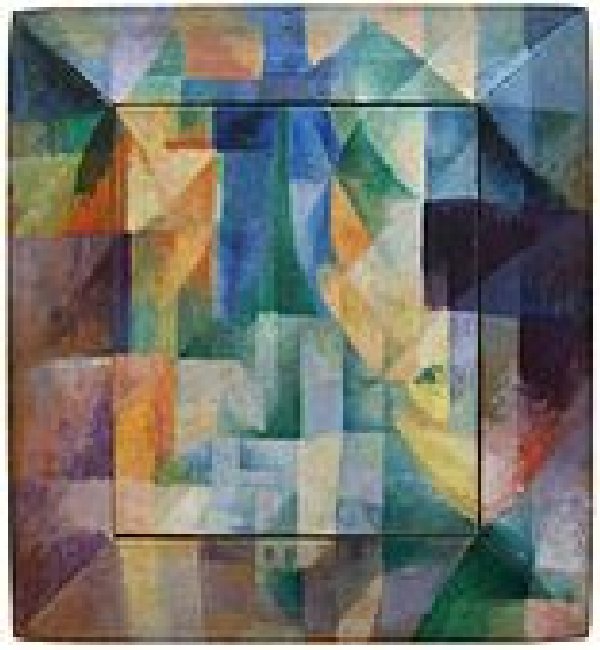

It was during the latter part of the nineteenth century that Bonnat had achieved financial stability and was able to indulge his passion for collecting art, especially drawings. He acquired sketches, drawings and prints by Rembrandt, Poussin, and Watteau as well as many others. Eventually, his collection included drawings and paintings from the best of his students and colleagues as well. Like many collectors, Bonnat not only loved the art he had acquired, but he also hoped to share it with a larger public and so he proposed the idea of building a museum in his native Bayonne that would ultimately house his own collection. With his deep roots in the region, continuing family ties to Bayonne, and undoubtedly a sense of gratitude for the support he’d received as a fledgling painter, Bonnat worked tirelessly at developing the new museum.

Léon Bonnat, installing his collection at the Musée Bonnat, Bayonne.

In 1902, he personally installed a large portion of his own unparalleled collection in the new Musée Bonnat. The collection was later enriched by the donation of the collection of Paul Helleu and his wife Alice, leading to its current name, the Musée Bonnat-Helleu. The chosen location of the museum was located at the corner of the two streets, Jacques-Laffitte and Frédéric-Bastiat, in the city centre, near the church of Saint-André where Léon Bonnat’s painting, Assumption of the Virgin can be seen. In 1896, the first stone of the future museum was laid by the Bayonne mayor Léo Pouzac and the classical-style building, in limestone, was completed eighteen months later. Inaugurated in 1901. When the Bonnat Museum opened, the artist and collector came to set up his collection himself, while writing a will by which he bequeathed almost all of his works to the National Museums with the obligation to deposit them in Bayonne.

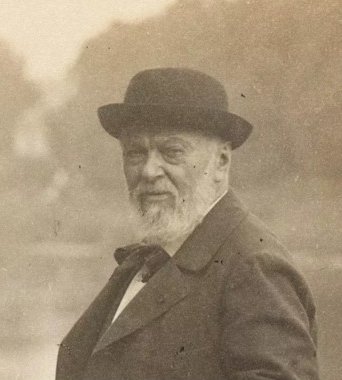

Self portrait by Léon Bonnat (1916)

Léon Bonnat died in Monchy-Saint-Éloi, a commune in the Oise department in northern France, on September 8th 1922, aged 89. Léon had never married and lived most of his life with his mother and sister.