(1900-1984)

Alice Neel had been receiving money for her involvement with the Works Project Administration (WPA). The WPA was the largest and most ambitious American New Deal agency, employing millions of unemployed people, mostly unskilled men, to carry out public works projects. The WPA employed musicians, artists, writers, actors and directors in large arts, drama, media, and literacy projects. At its height in 1936, this federal project, the Federal Art Project employed over 5,300 artists. The Arts Service Division created illustrations and posters for the WPA writers, musicians, and theatres. However, with the onset of World War II, mass unemployment ended as millions of men joined the services and so President Roosevelt decided that there was no longer a need for such a national relief programme and the WPA was closed down at the end of 1942. Alice was out of work and had then to turn to the state for public assistance which she kept drawing on for the next decade.

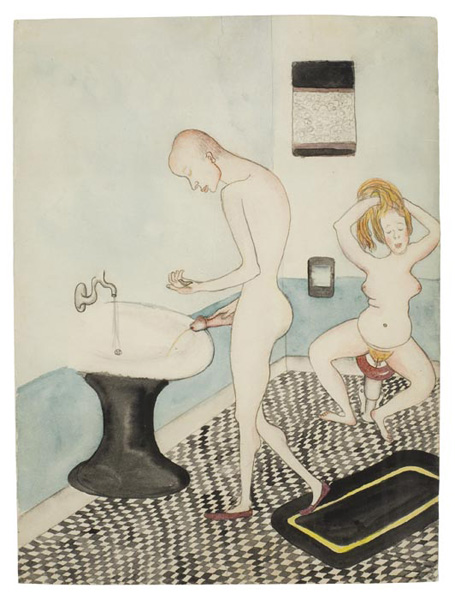

In March 1944 Alice held a solo exhibition at the New York Pinacotheca Gallery run by Rose Fried. This was her first solo exhibition since 1938. There were twenty-four of her works on display. The exhibition received mixed reviews. An article in the prestigious art magazine, ArtNews, described her work:

“…Neel’s paintings at Pinacotheca have a kind of deliberate hideousness which make them hard to take even for persons who admire her creative independence … Nor does the intentional gaucherie of her figures lend them added expression. However, this is plainly serious, thoughtful work and in the one instance of The Walk, it comes off extremely well…”

As Bob Dylan once said The Times They are a-changin and this was the point in time that Alice Neel found herself. After the 1944 Alice Neel’s retrospective exhibition at the Pinacotheca, gallery director Rose Fried never showed anything with a figure in it. According to Neel, Rose had become a pure abstractionist and the works that Alice produced were no longer wanted. The art world was changing; it had almost completely turned its back on Social Realism which had been the art form that had made Neel’s work so popular in the 1930’s. So, Alice had to change but as another famous lady politician once said, “this lady is not for turning” and Alice likewise would not change her artistic style to suit others. In an interview with Eleanor Munro for her 1979 book Originals, American Women Artists, Neel is quoted as saying:

“…I never followed any school. I never imitated any artist. I never did any of that…”

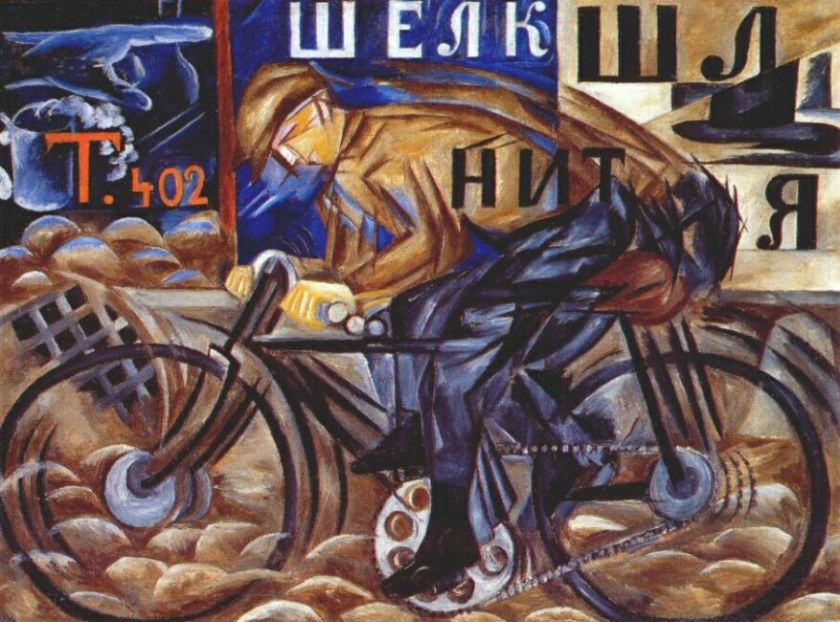

For Alice Neel, she knew what she wanted to paint and nobody or nothing was going to alter her artistic desires even though New York was now awash with European émigré artists who were leaders in the world of Cubism, Dadaism and Surrealism such as Max Ernst, André Breton, Marcel Duchamp and Salvador Dali, all of who had fled across the Atlantic to avoid the rise of Nazism. Alfred Barr had founded the MOMA and in October 1942, millionaire, Peggy Guggenheim, who was married to Max Ernst, had arrived in New York from war-torn Europe had opened a new gallery/museum. It was called The Art of This Century Gallery. The Art of This Century Gallery was situated at 30 West 57th Street in Manhattan and occupied two commercial spaces on the seventh floor of a building that was part of the midtown arts district which included the Museum of Modern Art, and three of the four galleries were dedicated to Cubist and Abstract art, Surrealism and Kinetic art, with only the fourth, the front room, being a commercial gallery.

During the 1950’s Alice Neel was kept under surveillance by the FBI. In a memo from their Miami office based on a 1954 letter sent to them by an informant they concluded that Alice Neel was:

“…a muddled romantic, Bohemian type Communist idealist who will carry out loyally the Communist sympathiser type of assignment, including illegal work if ordered to do so…”

Their file on her and her activities remained open until the early 1960’s.

In March 1953, Alice’s mother comes to live with her in her Spanish Harlem apartment. Sadly a year later Alice snr. aged 86, died from complications brought on by a broken hip. For Alice, this was yet another traumatic moment in her life She had always had to battle with depression and the death of her mother triggered the onset of the debilitating malaise for the next few years. Physically she put on weight and sought the comfort of alcohol.

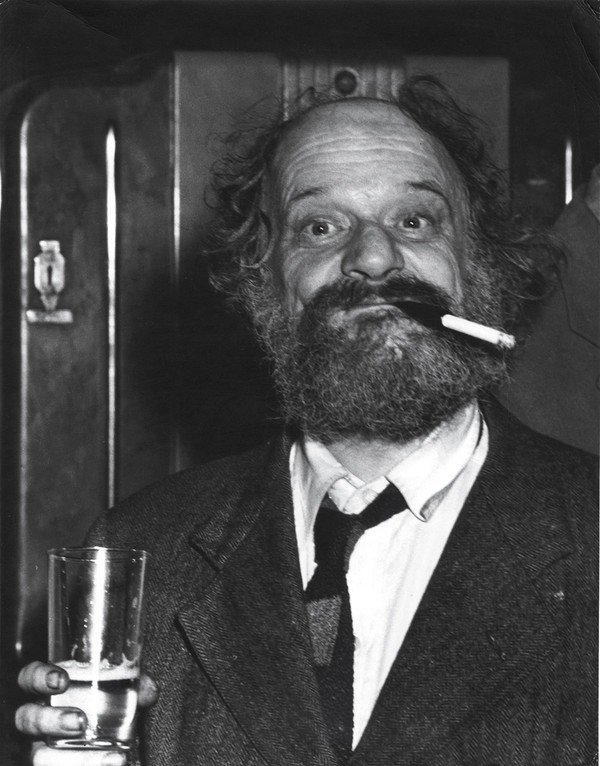

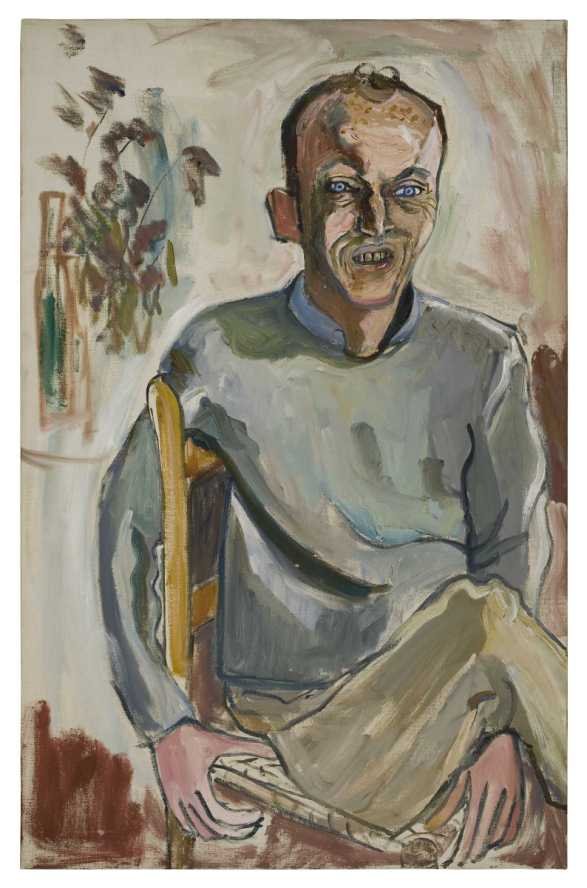

Alice often complained that she could not get any gallery space for her works of art. She painted prolifically but still wanted to exhibit them. The problem was that her genre of art had lost its appeal with the public. She was going through a difficult period with mental health issues and was attending therapy sessions with a psychologist, Dr Anthony Sterrett. He spent time with her trying to make her become more self-confident and self-assertive and it was he who persuaded Alice to contact Frank O’Hara to see if he would sit for her. O’Hara was an American writer poet and art critic who was working as a reviewer for the prestigious art magazine, Artnews, and who, in 1960 was Assistant Curator of Painting and Sculpture Exhibitions for the Museum of Modern Art. This position at the MOMA made him a prominent figure in New York City’s art world. He was looked upon as a leading figure in the New York School, which was an informal group of artists, writers and musicians who drew inspiration from jazz, surrealism, abstract expressionism, action painting and contemporary avant-garde art movements.

Alice completed two portraits of O’Hara in 1960 and they were looked upon as her breakthrough works. In the painting, Frank O’Hara, Alice has beautifully and faithfully captured his distinguishing and unique profile. The side view is hawk-like which is softened slightly by the bunch of lilac behind his head.

In stark contrast, the second portrait, Frank O’Hara No.2 is a more shocking depiction of the man. Our eyes are immediately drawn to his bad teeth, which looked like tombstones, his sharp nose and somewhat wild eyes. To be brutally honest, at first, he comes over as being ugly, even, dare I say, repulsive, but there is a vulnerability about Neel’s depiction of him.

Six years later, in the early morning hours of July 24, 1966, O’Hara was struck by a jeep on the Fire Island beach, after the beach taxi in which he had been riding with a group of friends broke down in the dark. He died the following day.

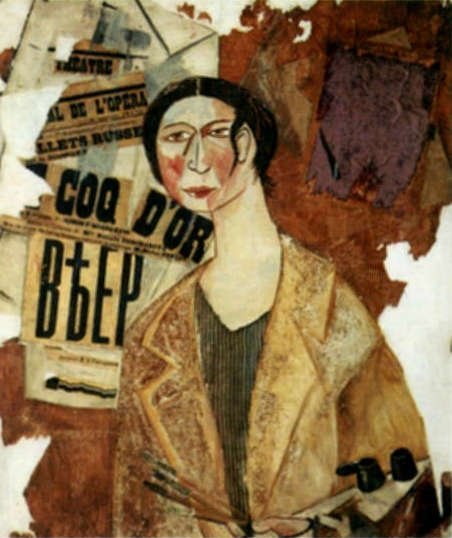

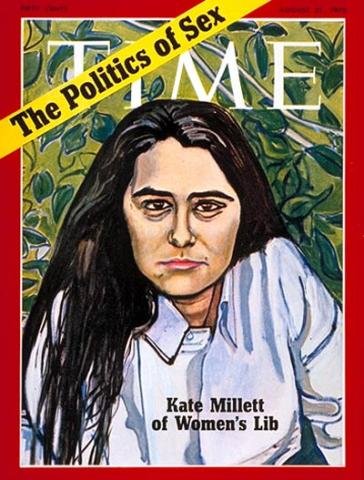

In America, the 60’s was dominated by the Civil Rights movement and the Vietnam War with its protests which swept the country. It was also a time when the second wave of the modern feminist movement emerged. It was a time when there was the growing cry for equal opportunity for women and it soon became one which could not be ignored. Enter Katherine Murray “Kate” Millett, best known as Kate Millett. She was an American feminist writer, educator, artist, and activist. She attended Oxford University and was the first American woman to be awarded a postgraduate degree with first-class honours by St. Hilda’s. She is probably best known for her ground-breaking 1970 book Sexual Politics, which was her doctoral dissertation at Columbia University.

This book became a bible for feminism and feminist protest was such a hot topic that in August 1970, Time magazine decided that Kate would be the face of the feminist movement and therefore should appear on the cover of their magazine. Millet was unimpressed by the way she was heralded as the embodiment of the movement and refused to pose for a painting by Alice Neel which would be used for the cover. She believed that no one person could presume to represent the objectives of the feminist movement. Time magazine was not to be put off by her refusal and instead asked Neel to complete the portrait, using a photograph. After the publication of the magazine Alice Neel and her art was always linked with the feminist movement but as Alice once quipped, she had been a feminist before there was feminism!

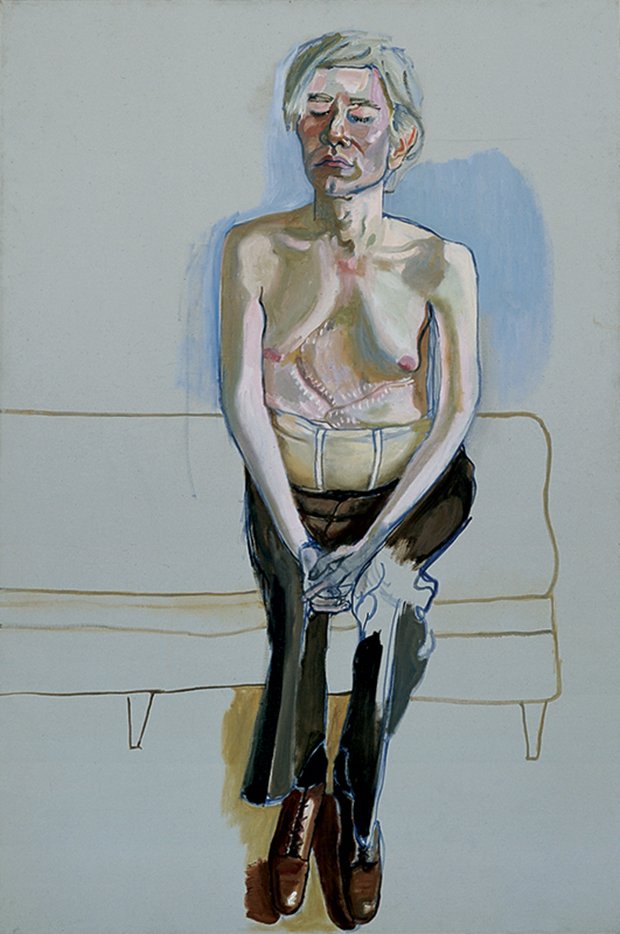

The year 1970 was also the year that Alice Neel painted one of her most famous works, a depiction of Andy Warhol. The painting can be found at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York and rather than me trying to describe the painting I have reproduced the words of the museum’s audio-guide which was put together by Trevor Fairbrother, an independent curator and writer:

“…It’s an interesting year for both of these artists. Alice Neel was seventy years old when she painted it, and in a sense, was just hitting her stride as an important American realist. She’d had an incredible career since the thirties, but she hadn’t really had much recognition until the wave of feminist interest in the arts in the sixties. And suddenly she was a forebear for a whole new generation of feminist artists and writers. The late sixties were much harder on Warhol. He’d been shot two years before Neel painted this portrait—an attempted assassination by a member of his artistic circle. In posing shirtless for Neel, he exposes the corset that he was required to wear for the rest of his life. He also bares his aging body, his chest sagging so that he almost appears to have breasts. She shows him—I think it’s this kind of essence of loneliness and vulnerability, but at the same time I think she knows that he knows that everybody is looking at him. He was very much invested in famous artists. He wanted to be a kind of brand-name Pop artist, and he certainly is that now, long after his death. He, Warhol, in a sense is rising to her challenge to sit for her, to be painted and to take his clothes off. And so, in a sense, he’s doing a brave thing, but he’s also―he’s getting through it by shutting his eyes and being very focused internally. I think part of the soulfulness of this picture is the fact that it might seem unfinished. I wouldn’t say it’s unfinished. I think she decided she had what she needed, and she stopped where she was ready to stop. The picture doesn’t need more…”

Fame came to Alice Neel late in life and she believed she had the right to bask in the glory. Her son Hartley recounted his mother’s feelings about this sudden fame:

“…She felt it was something she deserved. She basked in it. She really enjoyed it. When we were young, she struggled, waiting around for some critic to review her work, up or down. All of the sudden they were saying good things about her. Her paintings were on the walls, and people were buying her work. It was all different. She wasn’t bitter. She had a very upbeat attitude toward the whole thing…”

On October 14th 1980 at the Harald Reed Gallery on East 78th Street in New York a benefit dinner for the Third Street Music School Settlement was being held at which was the debut of an art exhibition entitled Selected 20th Century American Self Portraits, one of which was Alice Neel’s nude self-portrait which she had begun five years earlier.

She looks out at us completely oblivious or unconcerned about what we are thinking about why an eighty-year-old woman would want to depict herself naked. Does she feel vulnerable? There is no sign of that in her facial expression, in fact Neel’s steely gaze rivets us. She exudes an air of self-confidence, despite her less than picture-perfect body. We see her sitting regally in an upholstered chair with its hard vertical-striped arms which tend to accentuate her yielding and bounteous rolls of flesh. It is a “warts and all” portrait. She does not hide the visible signs of aging. Instead she has decided to reveal herself with characteristic truthfulness and somewhat defencelessness. Yet there is also a sense of pride in this depiction. In her right hand she holds a paintbrush whilst her left hand grasps a rag and, as we see no easel or canvas in the depiction, the two serve as artistic elements. The only personal accessory depicted is the presence of her eyeglasses which may have been added by her to remind us of her frailty and that she has passed her prime.

The painting was of course controversial and caused a stir but it also was testament that it was an audacious work by an artist who at the time was at the top of her form. The other unusual aspect of this work was that beside a few pencil-sketched self-portraits, it was her first self-portrait painting. The painting now resides at the National Portrait Gallery, Washington.

In 1970 Alice completed a work entitled Loneliness, which she ironically referred to as a “self-portrait”. It was about this time that her younger son Hartley had married Ginny and moved to Massachusetts.

Throughout her life Alice continued with her portraits of her family. Her future daughter-in-law, Hartley’s wife, Ginny featured in her 1969 work, Ginny in a Striped Shirt. Ginny was a feminist who looked upon Alice as a role model and they became good friends even before she became involved with Hartley.

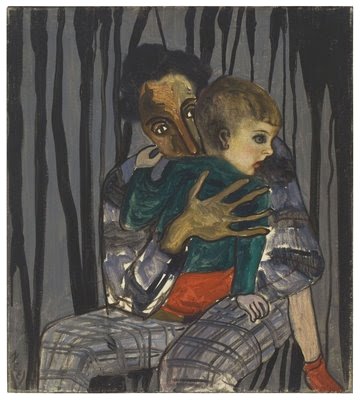

Her other daughter-in-law, Nancy, Richard’s wife and Alice’s assistant during the last two decades of her life, was depicted in Alice’s 1971 painting, Pregnant Woman. In the work, we see an image of her husband looming in the background.

In 1980 Alice Neel’s physical health takes a turn for the worse and after a series of tests it is decided that she had to be fitted with a pacemaker to regulate her heart rate. Four years later in 1984, during a routine visit to the Massachusetts General Hospital to have her pacemaker checked, X-rays indicate that she has advanced colon cancer which has already spread to her liver. She immediately undergoes surgery and afterwards returns to Vermont to stay with Hartley, Ginny and their children while she recuperates.

From the Spring to the Summer of 1984 she returns to New York and Spring Lake. With the help of her son and his wife, Richard and Nancy, and despite her rapidly deteriorating health, she continues with her busy schedule including an appearance on the Johnny Carson Show

Among her many commitments, interviews for the ArtNews article continue, and, on June 19th, she makes a second appearance on ‘The Tonight Show’ during which she insists that Johnny Carson visit her in New York to sit for a portrait. In July, she had to receive chemotherapy which further weakened her. Despite her weakened condition, she continues to paint.

Alice Neel died in her Upper West Side Manhattan apartment on October 13th 1984 surrounded by her family and was buried in a private burial ceremony at a cemetery near her studio in Vermont. On February 7th 1985, a memorial service for her is held at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

My look at the life and works of Alice Neel has been a long journey stretching over six blogs and yet I know I have missed so much out about her life and because she was a prolific artist I know I have only scratched at the surface with regards her works of art. I have been careful not to be judgemental with regards her lifestyle which probably added to her problems but she had a difficult and often sad life which often was beyond her endurance. She however always wanted to do her own thing and I leave you with one of her quotes:

“…”I had a very hard life, and I paid the price for it, but I did as I wanted,” Miss Neel said then. ”I’m a high-powered person…”

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

I have used numerous internet sources to put together this and the other blogs on the life and art of Alice Neel and I am currently reading a fascinating book about the artist by Phoebe Hoban entitled Alice Neel: The Art of Not Sitting Pretty. It is a very interesting read and one I can highly recommend.

Alice Neel’s art is being shown at several exhibitions in America but there are also a series of exhibitions of her work travelling around Europe at the current time including one I am due to visit next month:

Gemeentemuseum, Den Haag, Holland

(November 5th, 2016 – February 12th 2017)