The Latter Years

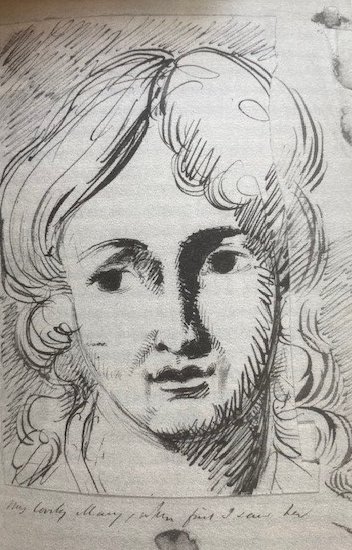

Portrait of a Girl by Clara Klinghoffer

Clara’s stay close to Menton with her husband and youngest sister had proved to be a great success and their plans to return home to London had been postponed on a number of occasions. The decision as to whether to leave their rented villa, Villa Aggradito, was taken out of their hands eventually as the owner needed the villa for a long-term rental over the coming winter, and the price for renting the villa was well beyond their means. They eventually moved and found Villa Josephine, a small ground floor flat with a small garden in the small Nice suburb of St. Sylvestre which was run by an elderly woman, Madame Rigolier. No sooner had the trio moved to their new home in September than Clara declared she was pregnant. Madame Rigolier immediately took on the role of “mother” and saw to all Clara’s needs. Clara’s husband on seeing that his wife was being well looked after decided to return to London with Clara’s youngest sister, Hilda. Clara was not being left alone as they invited Joop’s brother, who had not been well, to come and stay and they believed he would benefit from the warmer climate during the winter months.

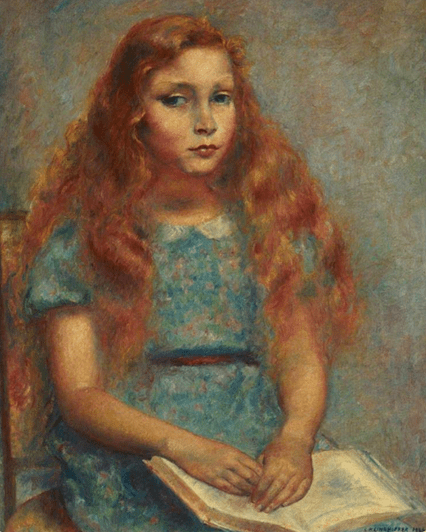

Portrait of a Young Girl by Clara Klinghoffer (1960)

With winter over Clara and Joop had to decide on their next move. Clara was not happy with the medical help she received from the local doctor but could not afford the charges levied by the hospitals and doctors in Nice. Clara and Joop left the Côte d’Azur in early March 1927 and headed to England with a two-day stopover in Paris. They managed to rent a small ground floor flat in the London suburb of Hendon.

Portrait of Cera Lewin by Clara Klinghoffer (1935)

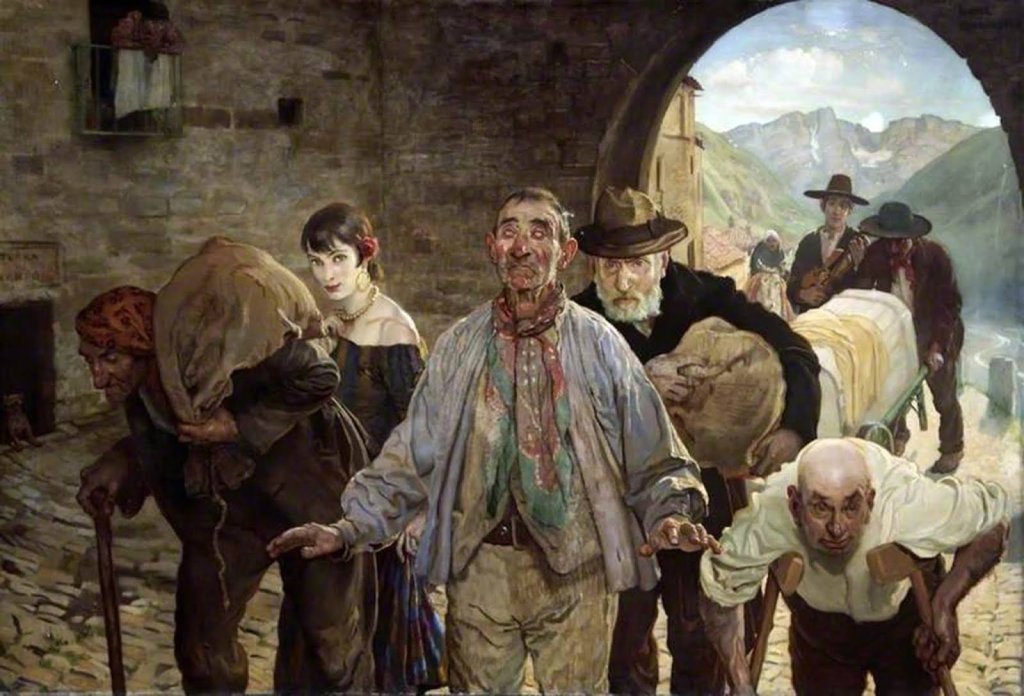

On May 28th 1927 Clara gave birth to their first child, a daughter, whom they named Sonia. The family finances were not good. It was true that Clara was selling her work to various galleries but by the time you deducted gallery commissions and the cost of painting materials there was barely any profit. Joop was struggling to find newspapers and magazine willing to buy his journalistic offerings and so the couple struggled financially. He was also aware of Clara’s family’s disappointment in him for not being able to provide for his wife. However, on a positive note, Clara’s fame as a talented young artist was spreading into Europe. The art critic of the leading Amsterdam Handelsblad wrote:

“…Clara Klinghoffer is among the few of her generation who have succeeded in circumventing the many pitfalls adhering to the work of most younger painters in England. Her recent ‘Old Troubadour is praised by leading critics as her best work to date. And rightly so, for in spite of the forcefully realistic conception of this picture, it is free of all coarseness, while the blending of its colours may safely be described as refined…”

Such favourable comments with regards to her work appeared in newspapers in England and throughout Europe and her work was being shown in a number of major exhibitions. Despite the continuing high praise from art critics the sale of he work was slow and her husband believed this was due to the poor publicity of the galleries were her work was on show.

My Sister Beth by Clara Kinghoffer (1918)

At the end of 1927 the family’s luck took a turn for the better when Clara’s husband, who could speak French and German, was offered a job as secretary to an American industrialist, Ray Graham, one of the three Graham brothers, who headed up the Graham Paige Motor Car Company of Detroit. He was arriving in Europe and needed a well-travelled multi-linguist as his aide-de-camp.

Girl with Plaits by Clara Klinghoffer

Ray Graham eventually returned to America and offered Joop a position in Detroit but Clara was horrified at this offer and her husband had to turn down the job. All was not lost however as Graham then offered to set up an agency for his car company in Paris and wanted Joop to head it up. Clara was not averse to living in Paris so Joop accepted the job offer. They relocated to the French capital in the Spring of 1928 and rented a small flat in the Avenue de Chatillon on the Left Bank which was an area where many artists lived. Their home was not at all what they expected and the manageress, who seemed to be an alcoholic, was both unpleasant and unhelpful. Clara was unhappy and wrote about their home and the surroundings:

“…High up from my window I look down upon the square, grey and desolate. The rain has not left off since last night. The immense puddles are filled with little bubbles that swim about till they burst. The square is new, and the road still unmade. To the right a house is in the making: an incomplete red structure, bricks, mortar and wood are piled up and scattered about. The workmen have not come. Factories and many-storeyed flats arise on all sides. A distant funnel gives out a grey smoke, with irritating slowness. At the end of the square a tram passes by, then a taxi. A group of people und.er umbrellas go past quickly. Then, for at least four minutes, not another human soul is to be seen…”

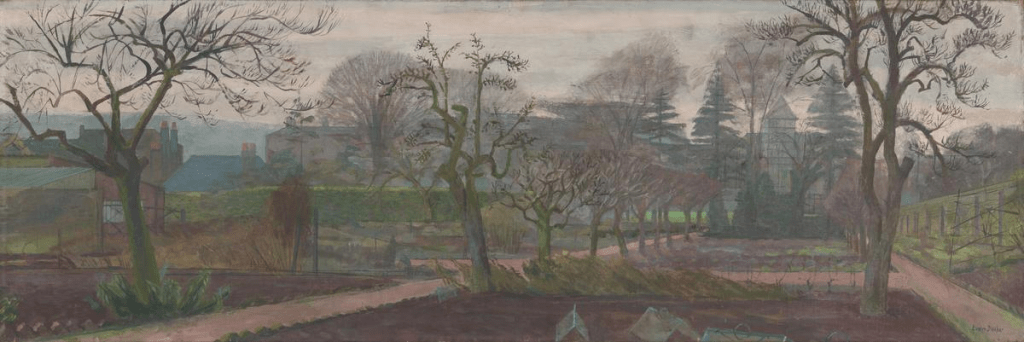

Heemstede Canal behind Rudi’s House by Clara Klinghoffer (1932)

Unhappy with their present flat they were pleased to hear about an ideal house for them from a friend of Joop, a fellow journalist. It lay some ten miles north-west of Paris in the village of Montmorency. The house was in the rue des Berceaux, close to the railway station, and both Clara and Joop were pleased to make it their home. The little ‘villa’, as they called it had a large corridor leading from the front door, spacious living rooms, a large kitchen and a bedroom. A wide staircase led to more bedrooms and the bathroom. At the rear of the property there was a small, enclosed garden. Both Clara and Joop were pleased with their new home.

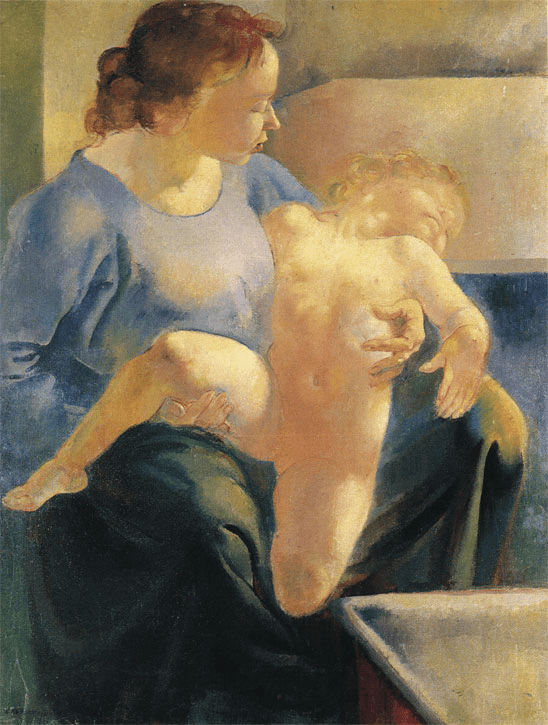

Mother and Child by Clara Klinghoffer

Having had her first solo exhibition at Hampstead Gallery in 1920, she held her first solo exhibition abroad in April 1928 when fifteen of her paintings and thirty-five sketches were displayed at the Nationale Kunsthandel in Amsterdam. Following the success of this exhibition Clara was bombarded by galleries, such as the Imperial Gallery, The New English Art Club and the Woman’s International Art Club, for more of her work for their future exhibitions.

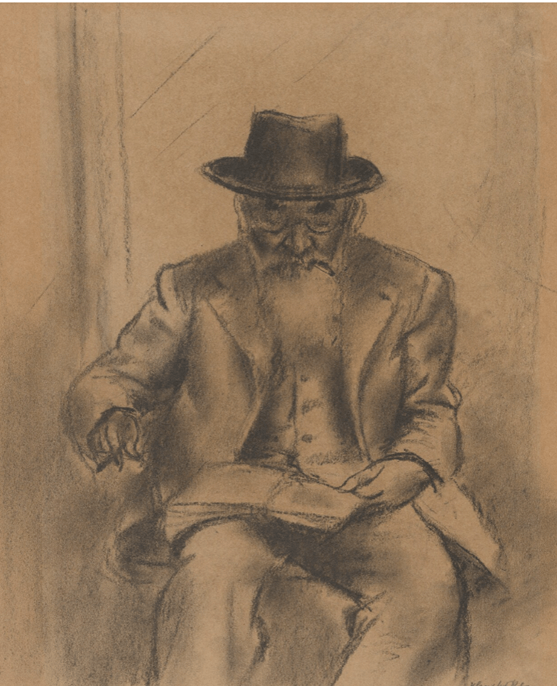

Untitled (One of Clara’s sisters) Chalk on paper by Clara Klinghoffer ©the artist’s estate. photo credit: the artist’s family

Joop was still working from his Paris office for the American car company Graham-Paige and Clara was so busy painting that she had to employ an au-pair, Anne-Marie, to look after baby Sonia. However in October 1929 life in America was rocked by the Wall Street crash and the Great Depression. The Presidential hopeful Herbert Hoover’s phrase “two chickens in every pot and a car in every garage” in his speech the previous year, now had a hollow ring to it. Joop’s boss’s car firm was all to do with high-end cars and they were hit badly. People were laid off and money spent on publicity, which was Joop’s area of expertise, was cut back. Joop began to realise that his job was in jeopardy. Fortunately, he heard that the Paris branch of the American publicity house of Erwin Wasey had advertised for a linguist to assist their executive in charge of all West-European advertising for Esso products. He applied for the job and was taken on. Meanwhile Clara had submitted a number of works to London’s Redfern Gallery and it had proved to be a great success even though financial problems were having an adverse effect on sales of works in both France and England.

Lakshme by Clara Klinghoffer (1918)

Life was to change in 1930 when, in July that year, Clara found herself pregnant with her second child. Around the same time Joop was “head-hunted” for a position at Lord & Thomas & Logan, a publicity company who were looking for a Dutch-speaker with a Dutch background who, at the same time, had the necessary experience in the international publicity field. Joop was exactly who they were looking for and he, and after speaking to Clara, agreed terms with his new employer. Clara was not unhappy about the move to The Netherlands as she had enjoyed her previous stay there and Amsterdam to London was a short distance to travel when she needed to talk to London gallery owners.

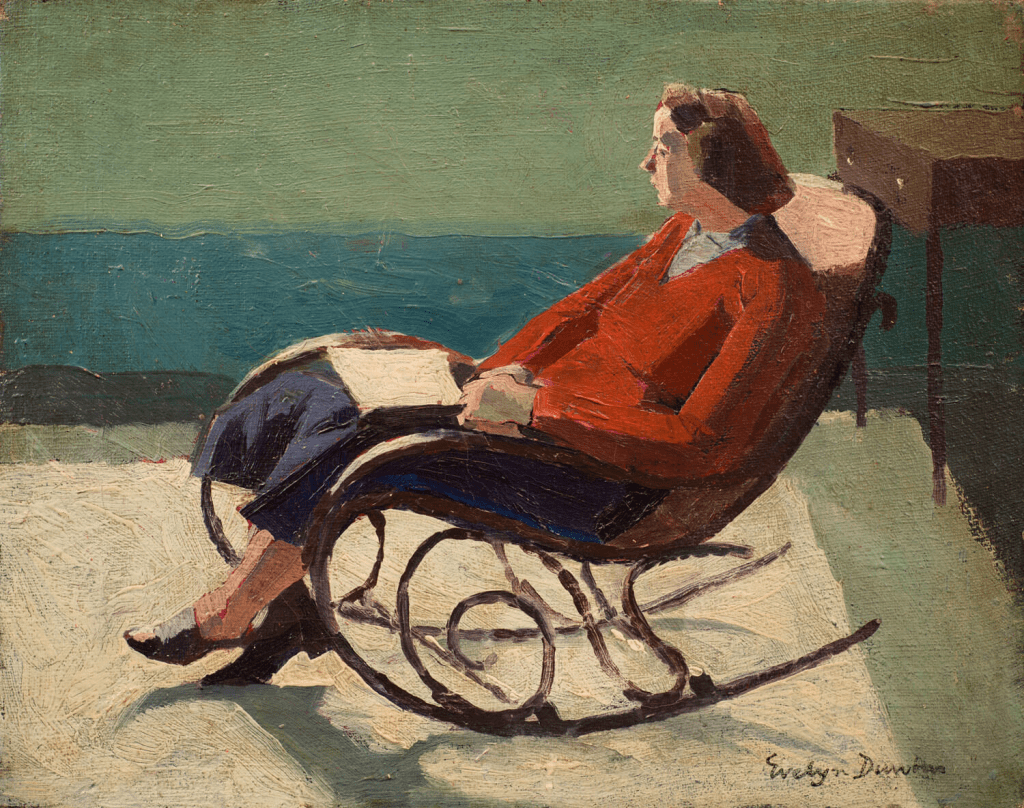

Grandmère and Sonia by Clara Klinghoffer (c.1930)

Joop travelled ahead to set up his Amsterdam office and a month later Clara joined him. The couple found it difficult to rent suitable accommodation in the city and eventually, in the Autumn of 1930, settled for a small house in Heemstede- Aerdenhout, just south of Haarlem. There they waited for their household furniture to arrive from Paris. Once again Clara, who was now heavily pregnant, needed help with looking after her daughter and husband and so they hired a maid to help with the chores. It was not a good time for Clara and she became very stressed.

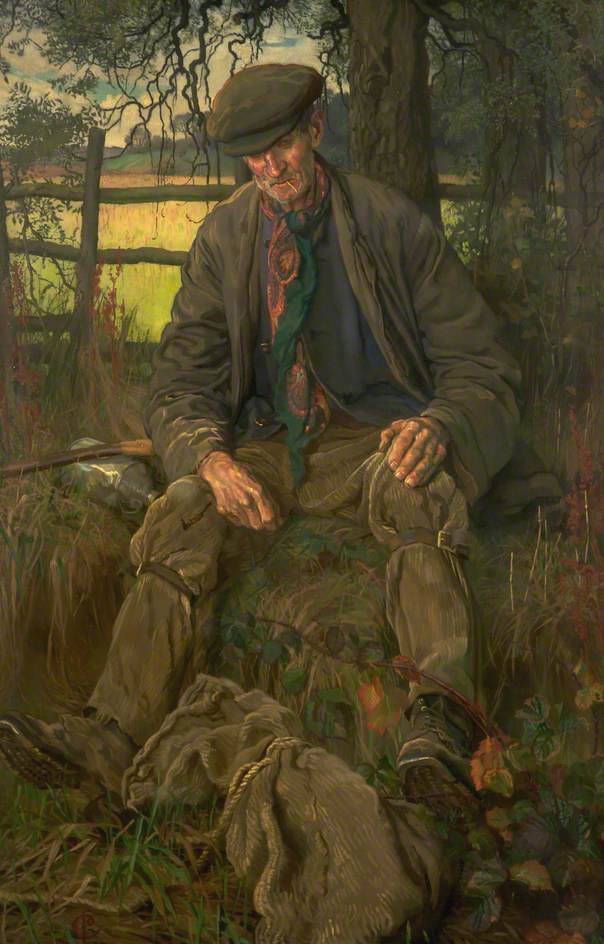

Portrait of Bananas the Pedlar by Clara Klinghoffer (1923)

On the twenty-fifth of January 1931 Clara’s second child, a boy, was born. They called him Michael Jacob. The name Michael was chosen because they simply liked the sound of it, and Jacob because that was the name of Joop’s late father. With the birth of her son, Clara’s mood and physical health improved. They even employed a German girl, Hettie, as nurse for the baby, but as Jews, they soon became wary of her and her questions relating to them and their families. It proved later that the nurse was feeding this information back to the German embassy. After confronting her, she hastily left the family home. Help did materialise when her sisters, Leah and Hilda came to live with them during the summer. In late 1931 Clara’s mother-in-law came to live with her and her son and she remained with them until she died in 1935.

Rosie with Apple by Clara Klinghoffer (c.1929)

The start of 1932 was a very sad time for Clara as she received news that Rosie, one of her younger sister and for many years one of her favourite models, had been ill for some times. At first her illness did not seem to be a very serious one. But her pains increased and then, on being examined by a specialist, Clara had to face the awful truth: that the girl, just about thirty years old, was dying of cancer. Clara travelled to London at once and stayed there for some time, drawing as she always did and making an exquisite painting of Rosie. Several doctors were consulted; even a Dutch physician of Utrecht who supposedly had a cure for cancer, was persuaded to send each week a bottle of his magic medicine to London. But it was, of course, all in vain. Rosie died that summer. It was a very hard blow. From now on the magic circle of the seven Klinghoffer girls existed no longer. For some time the loss of Rosie paralyzed Clara’s desire for work. Then, gradually, she took up her brushes again and painted.

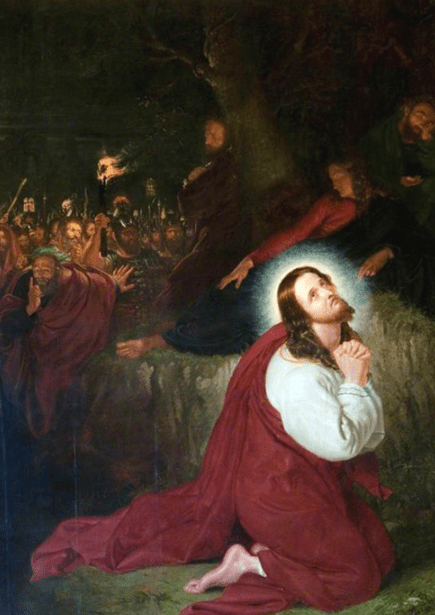

Giuseppina by Clara Klinghoff (1934)

In 1932 Hitler came to power when the Weimar Republic collapsed. The National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands (Dutch Nazi party) led by Anton Mussert became more prominent following the rise of Hitler and grew more challenging, stressing ever stronger the anti-semitic principles of the Filhrer. On February 27th 1933, the Reichstag in Berlin was set alight by a twenty-three-year-old Dutchman Marinus van der Lubbe and, as in Germany, anti-semitic tensions in The Netherlands grew fanned by inflammatory articles appearing in Mussert’s weekly newspaper Volk en Vaderland (People and Fatherland). Notwithstanding the political tensions Clara and Joop managed to get away and have a holiday in Taormina, Sicily where they stayed in a small hotel which had beautiful vistas across the bay. They became friendly with the owner, Ettore Silvestri and his daughter Giuseppina who agreed to pose for Clara. She said that posing for long periods would be a problem to her and Clara and Joop discovered she had been very ill for five years, an illness that tired her. In August 1935 whilst back home Joop and Clara received a letter from Taormina informing them that sadly, Giuseppina had died.

One-eyed Mexican Farmer by Clara Klinghoffer (1962)

In 1939, the anti-semitic feelings in The Netherlands had begun to escalate and there was talk of a Nazi invasion of the country and so Clara and Joop decided to move to London. They packed up all their furniture and Clara’s paintings and they were stored in a warehouse in Haarlem but sadly their property was plundered during Nazi occupation. When the Second World War ended Clara divided her time between her studios in London and New York. In New York Clara held a number of exhibitions of her work but the interest in her figurative art was waning as the art world had latched on to the new abstract expressionism, by the likes of Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning and suddenly Clara’s work was considered unfashionable and she struggled to attain exhibition space, even in London. In 1952 she visited Mexico and she was attracted to the colourful landscapes and had no trouble finding locals who would model for her. Her last exhibition was in 1969 at the Mexican/North American Cultural Institute in Mexico City. She then returned to Europe and spent time in Southern France. Her health began to deteriorate and she returned to London where she died on April 18th, 1970 at the age of 69. Clara is buried at the Cheshunt Cemetery near London.

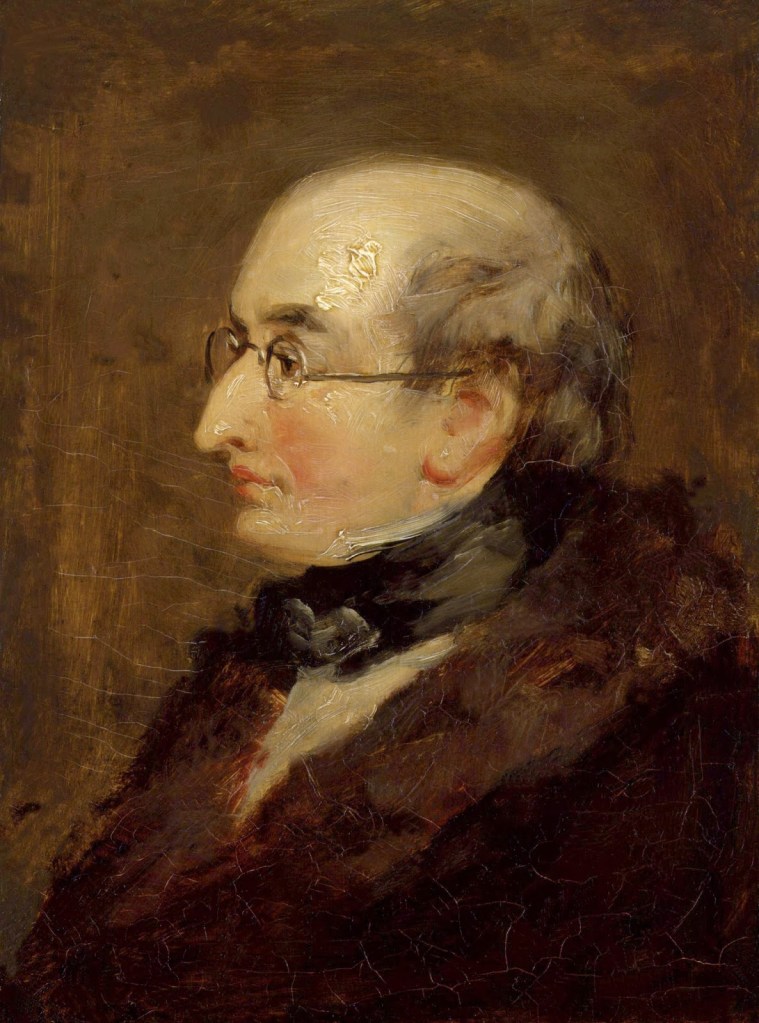

Clara Esther Klinghoffer (Stoppelman) 1900-1970

I end with a 1981 quote by Terrence Mullaly of The Daily Telegraph who wrote about Clara and her artistic talent:

“…If ever there was an artist who for some time has been unjustly forgotten, it is Clara Klinghoffer … While the temporary eclipse of her reputation was not, given trends in the visual arts, surprising, it is certainly lamentable. She was a portrait painter of sensitive talent and, above all, a fine draughtsman … In her work her obvious sensitivity towards her sitters is manifested, and enforced by her ability not only to suggest weight and substance of a body, but also to convey mood … When much more celebrated artists are forgotten, she will be remembered…”

Information for this blog was found in many sources but the most important ones were:

Clara Klinghoffer- 20th century English artist

Clara Klinghoffer: the girl who drew like Raphael and Leonardo