The best laid plans of mice and men….. etc etc. I had intended to travel to London yesterday and visit a couple of art galleries including the Queens Gallery to see the Dutch Landscape exhibition but because of a certain visitor by the name of Mr Obama the Buckingham Palace Gallery was closed to the public. However I did go to the National Gallery to see The American Experiment, a small exhibition of paintings by the Ashcan School of painters which was small but made for excellent viewing. More about that later in the week.

As I had time on my hand I decided to visit the Richard Nagy private gallery in Old Bond Street and have a look at an Egon Schiele exhibition. I am not sure what I expected to find at this display but the weekend newspapers gave it a “Must not miss” tag so I had high hopes. They were not wrong. It is a small but excellent exhibition and you should really try and visit it before it closes on June 30th. I remember when I visited Vienna at the end of last year; the three beloved artists of that country were Klimt, Kokoschka and Schiele. This exhibition had more than forty paintings and drawings by Schiele which had not been previously seen together in a UK gallery and which of course is just the tip of his iceberg as he has more than four thousand works attributed to him.

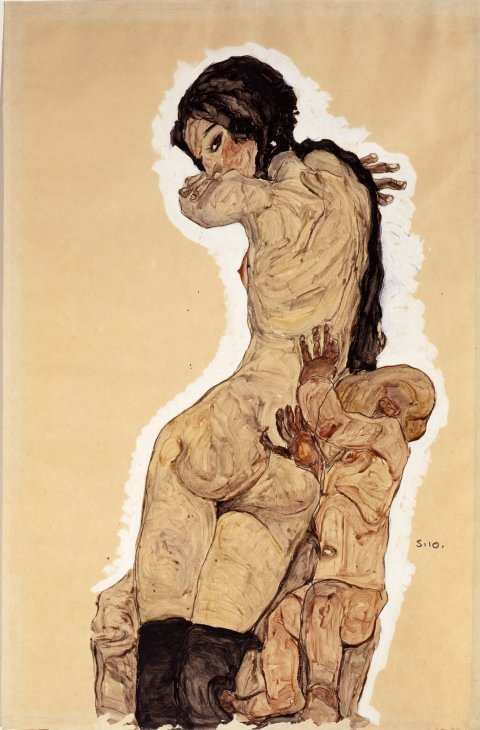

I intend to look at the life of Schiele over the next two days and see if I can offer you examples of his work, which are not likely to offend my readers. I am not sure one can shy away from the word “pornographic” by clouding it with the word “art” but then it is a matter of opinion. You will be able to look at his more risqué works on the internet and then decide for yourself. It is up to each individual to decide when art crosses the line from being erotic and sensual to becoming pornographic.

Egon Schiele was born in 1890 in the small Austrian town of Tulln, which lies on the River Danube, just outside Vienna. He was the first and only surviving son of Adolph and Marie Schiele. His mother Marie came from Krumau (now Cesky Krumlov) in Bohemia and his father Adolph, an Austrian, was a station master for the State railways. Schiele had two sisters, Melanie who was four years older than him and Gertrude who was four years his junior. They all lived with their parents in an apartment above the Tulln train station which was also the place of work for their father. Egon went to the local school and soon developed a love for art. His parents hoping he would be university-material enrolled him at the age of eleven as a boarder at the Krems Realgymnasium some twenty-five miles from their home. Although his father had hoped he would use his artistic skills coupled with his seeming love of trains to become a railway engineer, it was not to be. His father lost patience with young Egon when he fell behind in his academic studies due to his fixation on art and at one point his father destroyed his sketch books.

In 1904 Adolph was taken ill having contracted syphilis. He had to leave his job and that year he died. It was a prolonged and painful death, with its sickness and eventual insanity and it affected Egon badly. Ten years later he wrote to a friend recalling this harrowing time. In the letter he wrote:

“… I don’t know whether there is anyone else at all who remembers by noble father with such sadness. I don’t know who else is able to understand why I visit those places where my father used to be and where I can feel the pain…….Why do I paint graves and many similar things? Because this continues to live in me….”

Later, his sister, Melanie, would assert that her brother’s promiscuity was a challenge to the “Gods” to inflict him with the same disease which had killed his father. The death of the main breadwinner caused the family financial hardship and Egon’s mother had to turn to Egon’s uncle, Leopold Czihaczek for help. He eventually became joint guardian of the boy.

Egon attended the School of Arts and Crafts in Vienna which was the old alma mater of Klimt. Schiele excelled at this school, so much so, that in 1906, he transferred to Vienna’s Akademie der Bildenden Kunste, the more traditional route for aspiring artists. It was around this time that he met and was mentored by Gustav Klimt who appreciated the young Schiele’s talent. Klimt even bought some of Schiele’s works as well as swapping some of his own work with that of the young would-be painter. Schiele owed a lot to Klimt who put him in touch with potential buyers and Schiele held his first exhibition at the age of 18. A year later in 1909 he left the Academy disillusioned with its teaching style and artistic constraints. He joined a group of like-minded painters to form the Neukunstgruppe, (New Art Group).

Although Schiele had benefited immensely from what he learnt and who he met at the Academy he had felt artistically constrained and once away from the establishment he began to delve into not just the human form but also human sexuality. It was this aspect of his paintings and drawings which was to engender controversy. His critics described some of his works which focused on death and sex as grotesque and pornographic. His portraits, often of nudes were painted in a realist manner and that was what probably upset some of his detractors. Schiele took part in the International Jagdausstellung in Vienna in 1910 and he showed his life-sized, seated female nude. Allegedly when Emperor Franz Joseph saw it he turned away muttering “This is absolutely hideous”

The Egon Schiele painting I am featuring in My Daily Art Display was painted by him in 1910 and is entitled Woman With Homonculus. A homunculus being a scale model of a human body and refers to the seated figure to the right of the woman which tries to cling to her. This is undoubtedly an erotic painting of a woman with her back to us, wearing only a pair of black stockings. She has twisted her upper torso around to look over her shoulder at us in a coquettish fashion. The reddening with rouge of the tip of her left breast and nipple can just be seen and it is this “just be seen” look which tantalises the viewer. It is most certainly a pose and a look of a seductress and I believe she is wondering what we make of her body – but I am sure she already knows the answer.

Tomorrow I will complete the life story of Schiele and show you a few more of his paintings and sketches.