Rowland Frederick Hilder

The artist I am looking at today is the American-born English watercolourist Rowland Frederick Hilder, a great painter of English landscapes and seascapes. Rowland was born to Roland and Kitty Hilder (née Fissenden) on June 28th, 1905 at Great Neck, a village on a peninsula on the North Shore of Long Island.

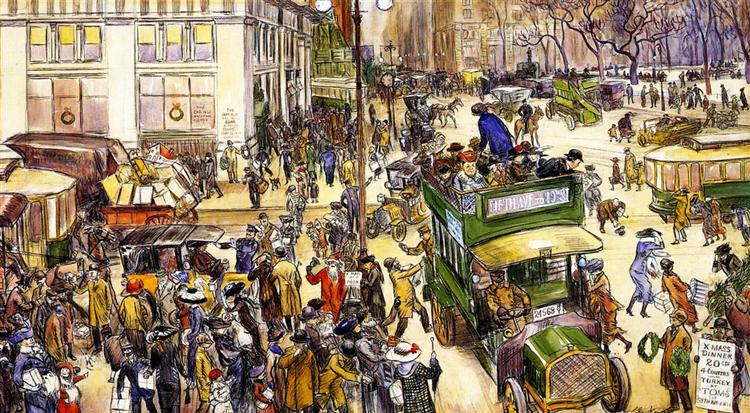

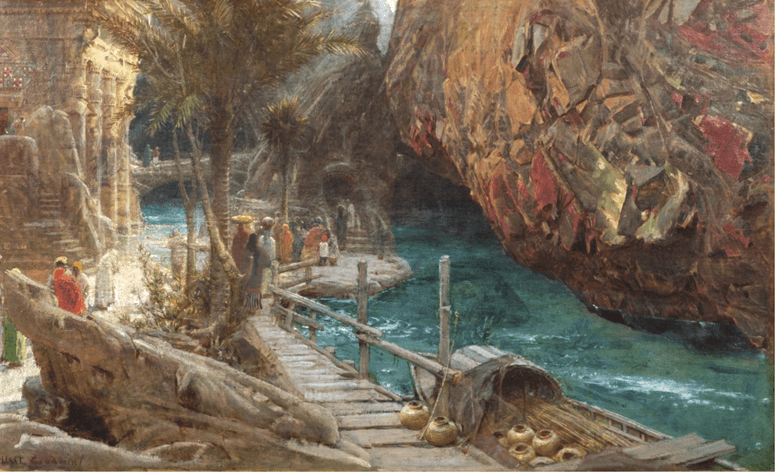

Tyringham Hall by Rowland Hilder

In early 1915, following the outbreak of the First World War, Rowland’s father decided to return to England, and his native county of Kent, where his forbears had lived and he would enlist in the army and serve his country. The Hilders set sail on the SS Lusitania, a liner which would be destroyed by a German submarine on its next transatlantic crossing in May of that year.

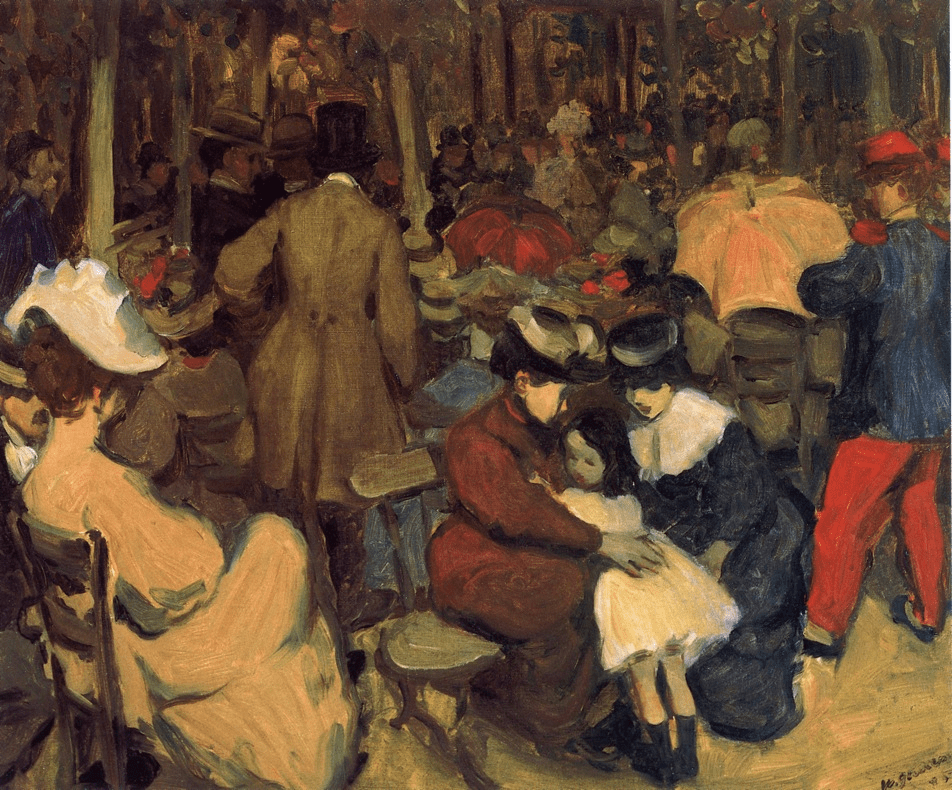

The First Snow by Rowland Hilder

Life at school was not a happy one for Rowland. He was a tall gangling boy who had a pronounced American accent which went against him, both with his fellow students and some of the teachers. Hilder was academically challenged and found it difficult to spell correctly. Fortunately for him, the art master at the school encouraged him to sketch and advised his parents to let their son follow his love of art.

Watermill, Cambridgeshire by Rowland Hilder

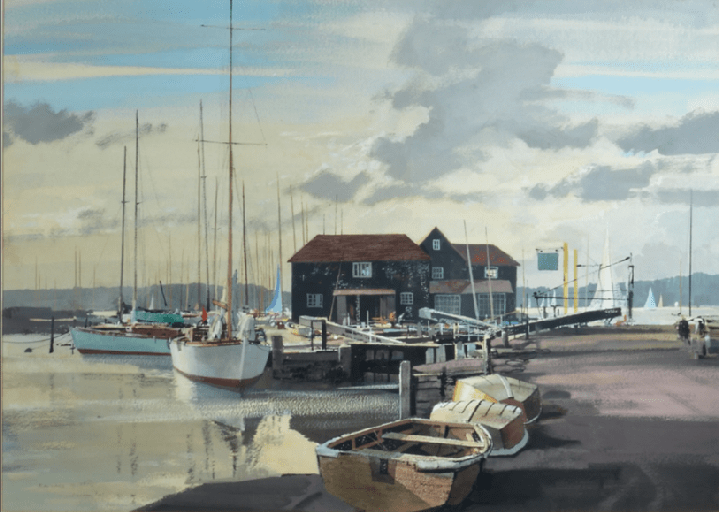

Birdham Pool, Chichester by Rowland Hilder

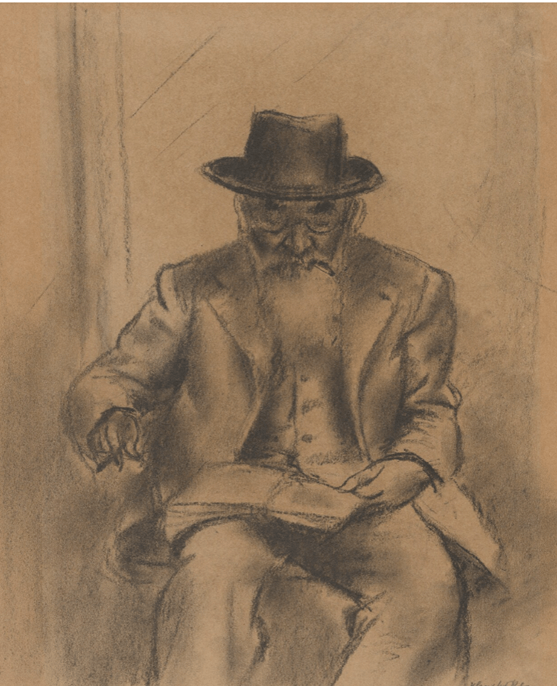

Having shown a great talent for sketching, in 1921, at the age of sixteen, Rowland Hilder enrolled at Goldsmiths’ College in London, an art establishment which had established a reputation for nurturing fine draughtsmanship in its students. He was initially placed in the etching class but couldn’t stand the smell of the acid so switched to illustration. While studying illustration at Goldsmiths one of his tutors was the illustrator, Edmund (E.J.) Sullivan who had contributed illustrations for many of the great journals and magazines of the 1890s and Hilder looked up to him and regarded him as a true professional. Sullivan taught Hilder the discipline of line drawing and with it the essential structure that holds any work of art together. Hilder remembered his days at Goldsmiths and how Sullivan had encouraged his students to spend a great deal of time sketching. Rowland was also introduced to the art of one of the greatest draughtsmen of the past, Albrecht Durer.

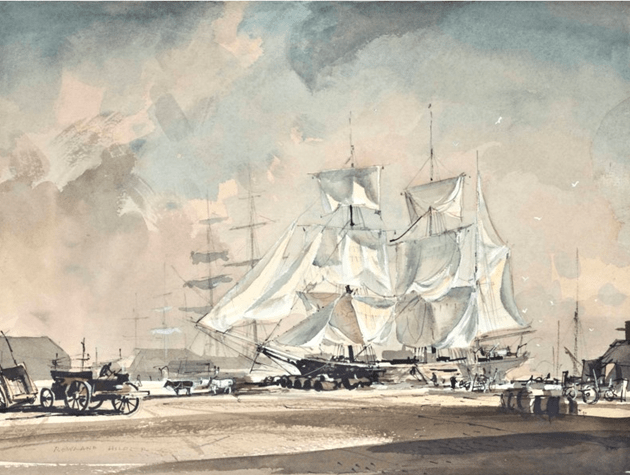

In Days of Sail by Rowland Hilder

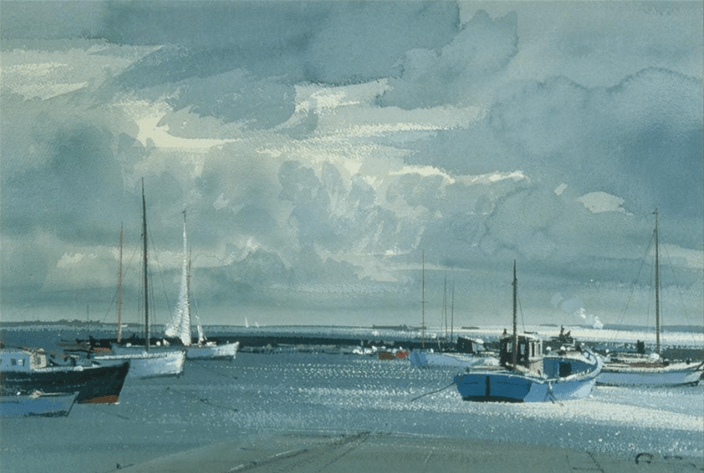

Poole Harbour by Rowland Hilder

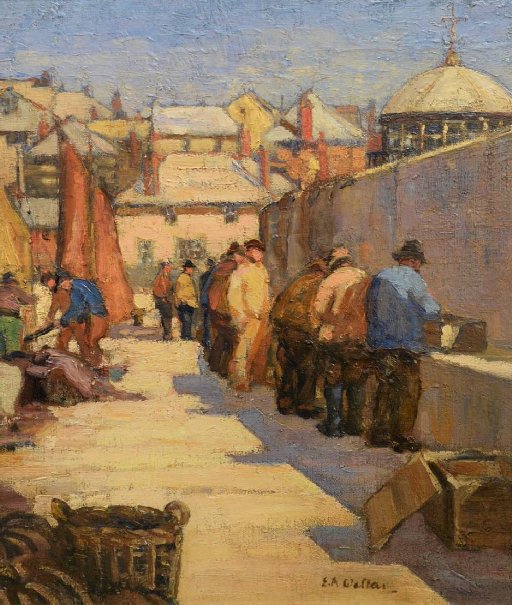

As time went by at Goldsmiths Rowland began to think about his future art career and what genre of painting he would like to follow. At first he decided to become a marine painter and he spent much time on the waterfront sketching and painting boats. Around this time he also won a prize in a competition sponsored by Cadburys for his work. The prize, a travelling scholarship, and Rowland used the money to travel to the Netherlands to study the works of the great Dutch Masters who depicted magnificent marine scenes.

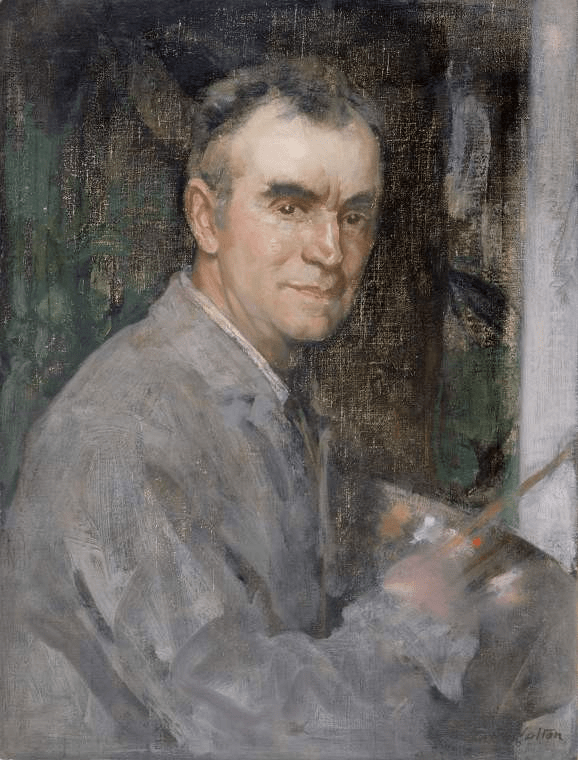

Artist at Work (Edith Hilder by Rowland Hilder

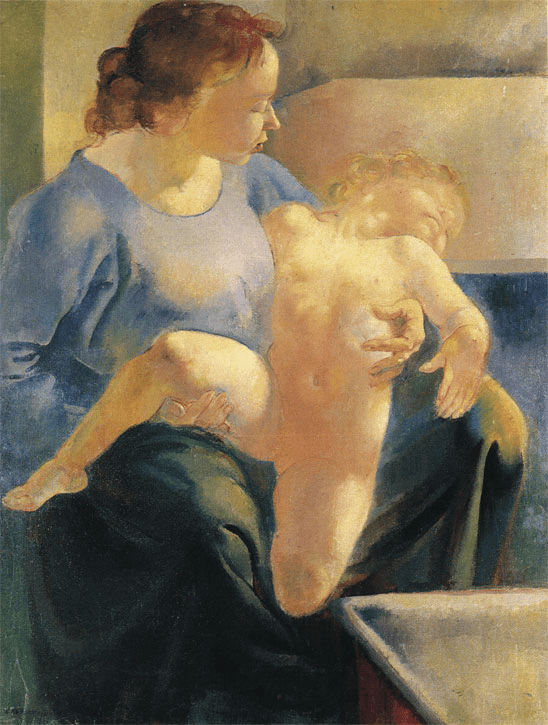

Whilst studying at Goldsmiths, Rowland met fellow student Edith Blenkiron. She was a botanical painter, and her depictions were often to be found on fabrics or pottery, illustrations for books, or simply painting pictures which could be hung on people’s walls. She said that she was most happy when working direct from nature. Love blossomed and the couple married and went on to have two children.

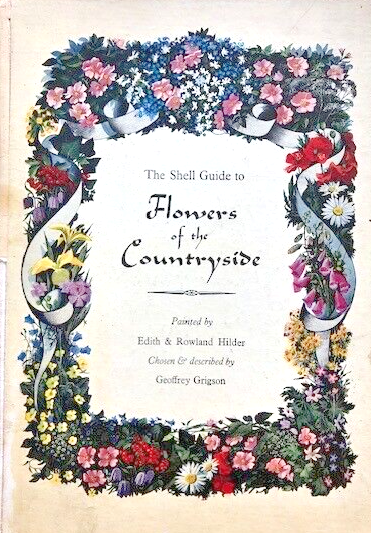

Floral Arrangement by Edith and Rowland Hilder

Edith’s beautifully drawn and botanically accurate floral watercolours, with landscape backgrounds often painted by her husband proved very popular. It was her floral depictions which brought her a following in her own right rather than be just considered as the wife of the artist Rowland Hilder.

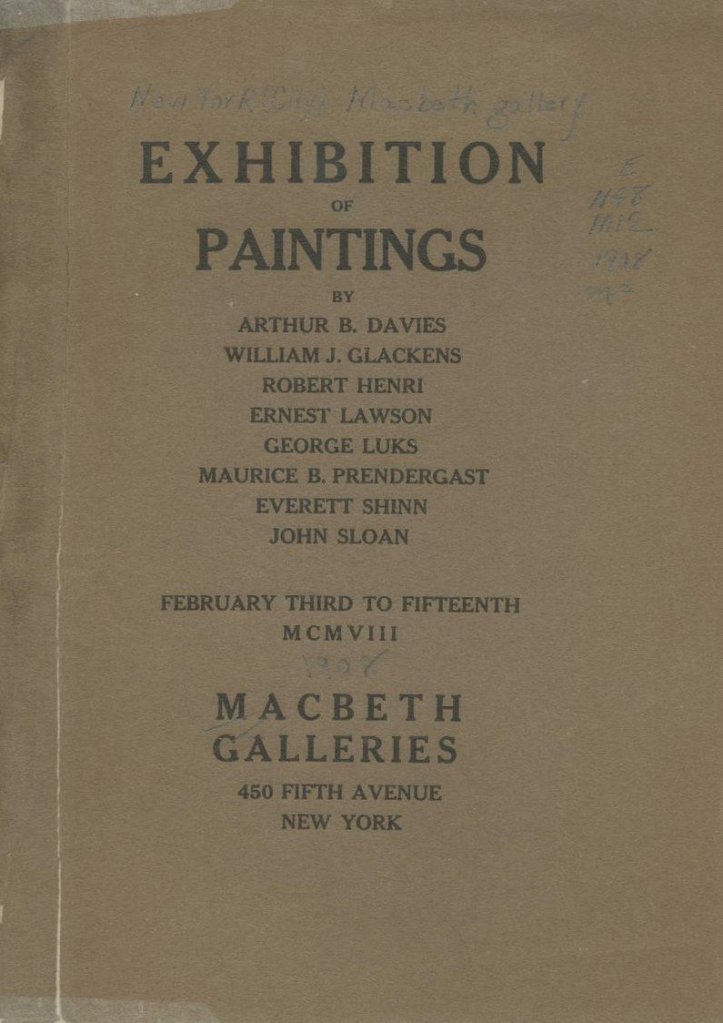

During his period at Goldsmiths he completed a large drawing of a cable ship which was bought by two Royal Academicians, William Orpen and Arnesby Brown on behalf of the National Gallery of Australia . Whilst at Goldsmith he was also approached by two book publishers. Jonathan Cape and Blackies, to illustrate their books of sea stories. Both publishers were pleased with Hilder’s illustrations and in 1928, publishing house, Jonathan Cape, asked Rowland if he would contemplate switching from is favoured marine and seascapes and concentrate on depicting countryside landscape scenes as they would like him to illustrate books for Mary Webb, an author who had achieved considerable fame for her novel Precious Bane.

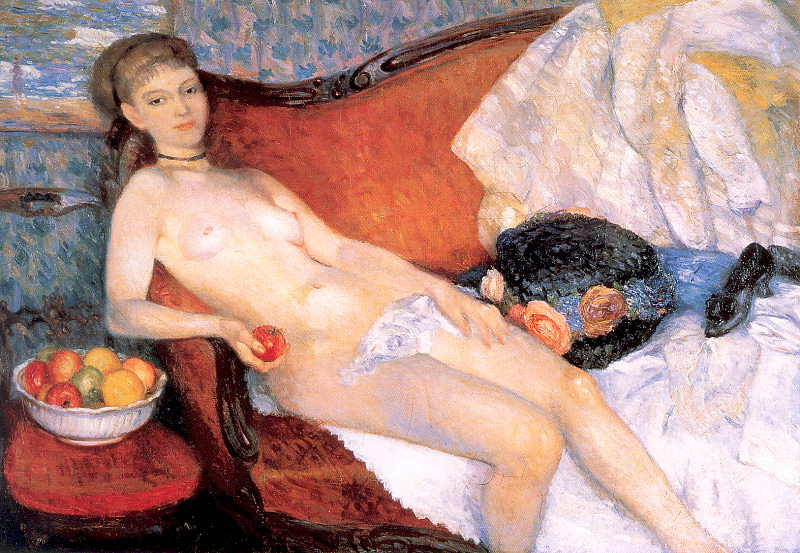

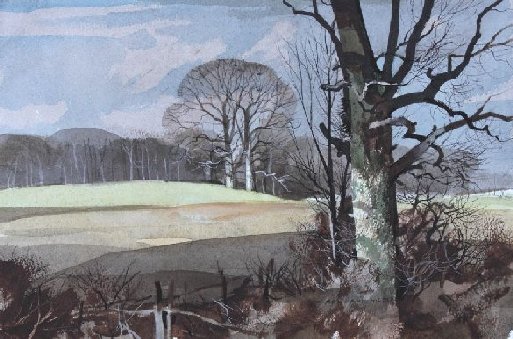

The publishers arranged that winter for Rowland Hilder, his mother and his soon to be wife Edith, to stay in Mary Webb’s cottage in the Shropshire countryside so he could familiarise himself with the rural surroundings in which her novel, Precious Bane, was set. Both his wife and mother would remain in the warmth of the indoors during the day, whilst Rowland would trudge through the snow and the frozen winter ground avidly collecting material, both for use in his illustrative work, but also for his newly found love of depicting the landscape in wintry conditions in his paintings. Hilder was mesmerised by the rural beauty. Views of the winter landscape astounded Hilder and he realised that the depiction of such beauty could prove popular with the public. Many of his pictures were seen on greetings and Christmas cards.

World War II poster by Rowland Hilder

When the Second World War broke out in 1939 Rowland Hilder was one of the first artists who was approached by the government to design war posters which would rally round the people of Britain. One such poster designed by him was Convoy your Country to Victory Save and Lend through our National Savings Group, which was issued and sponsored by the National Savings Committee, London; Scottish Savings Committee, Edinburgh; Ulster Savings Committee, Belfast and printed for H.M. Stationery Office. The poster depicted merchant navy ships being escorted across the treacherous Atlantic Ocean under the watchful eye of a Royal Navy vessel which is seen flying the White Ensign.

Garden of England by Rowland Hilder

Another project Hilder was involved in was to provide black and white drawings for an illustrated bible. This wartime bible contains many beautiful depictions of the English landscape, by Rowland Hilder as well as one or two other artists working in the same style. The idea of this new book was stated in its preface – to give the people of today a copy of the Bible that is easy to read and that will take them at once to the heart of its message. Some of the drawings depicted Biblical themes whilst others illustrated daily life in the mid twentieth century.

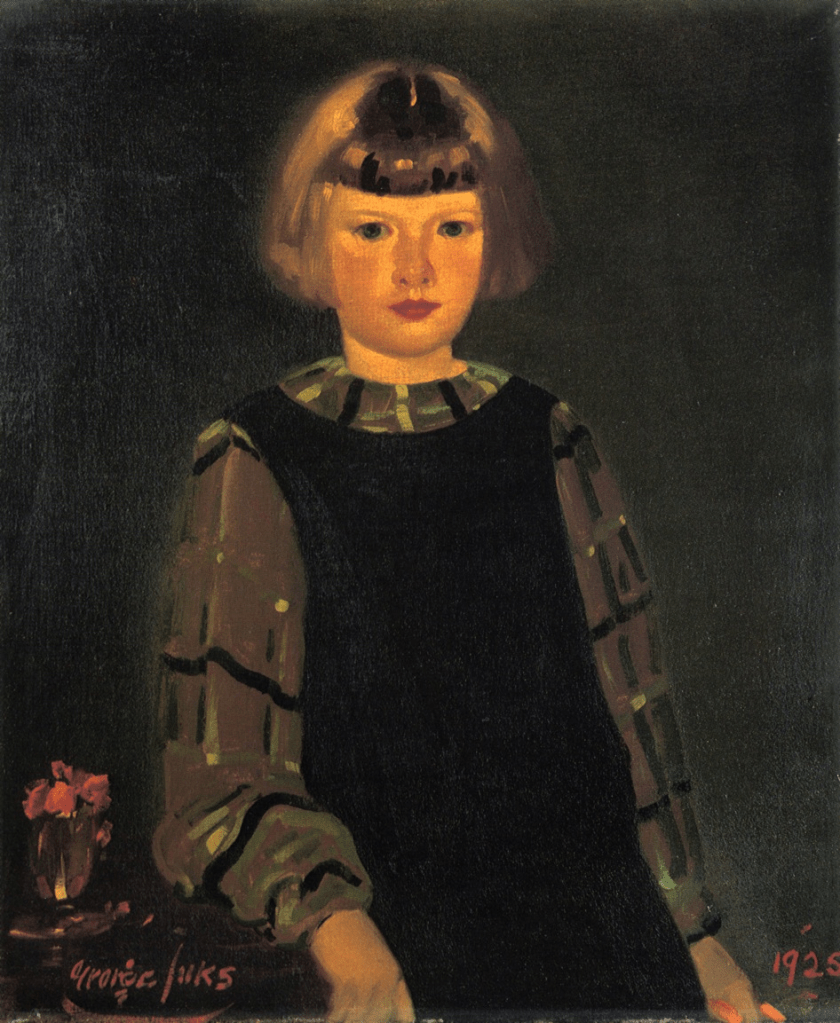

Treasure Island (1929) by Robert Louis Stevenson with twelve colour plates and some black and whight vignettes by Rowland Hilder

Rowland Hilder’s received numerous book illustration commissions included Herman Melville’s Moby Dick and Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1929 edition of Treasure Island.

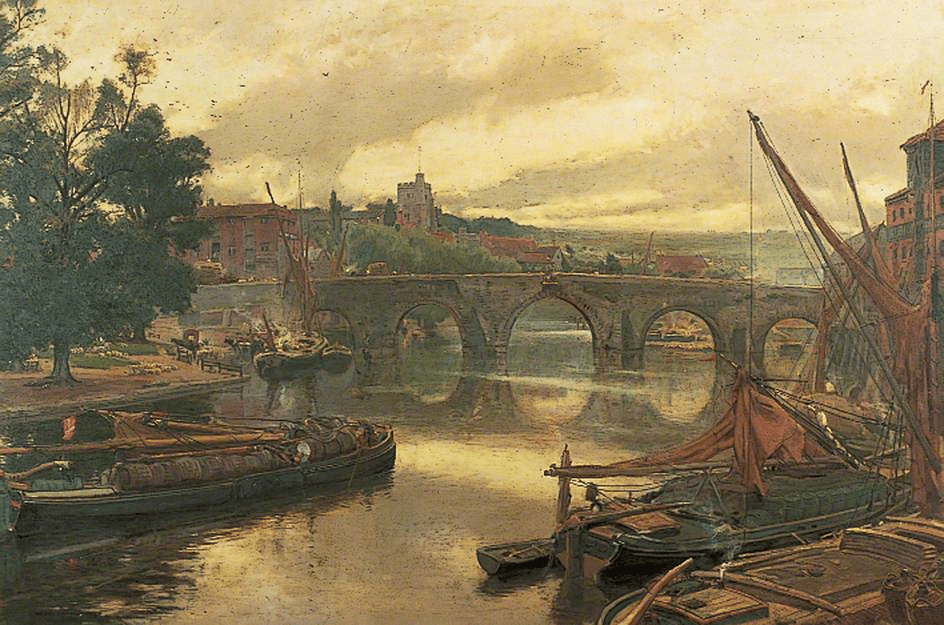

Landscape with Oast Houses by Rowland Hilder

Hilder achieved great popular success with his portrayal of the English countryside, notably Kent, with the characteristically delineated trees and oast-houses.

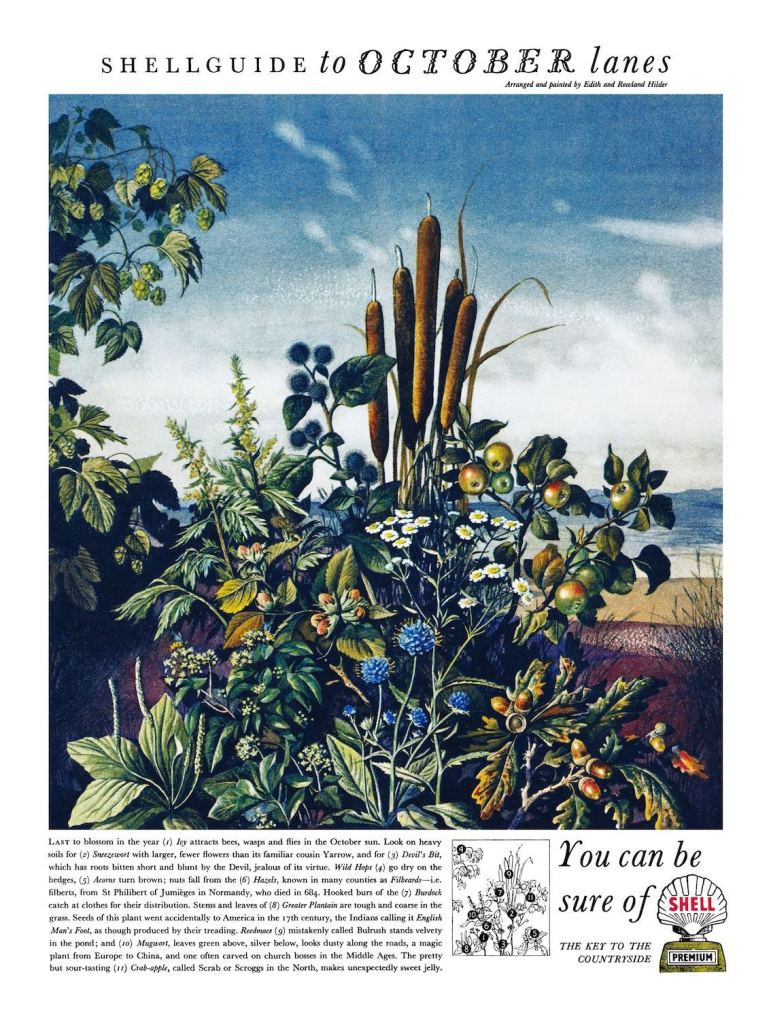

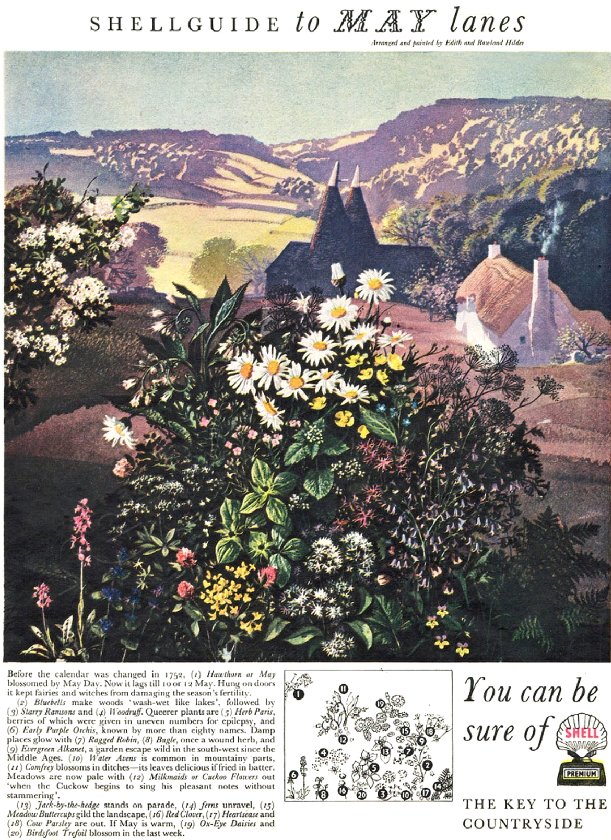

Shell advertising poster illustrated by Rowland and Edith Hilder

Shell Guide to May Lanes arranged and painted by Rowland and Edith Hilder

From the 1920s and into the 1950s, the Shell Oil company produced some beautiful advertising posters which many said, were the most beautiful ever produced. Rowland and Edith Hilder collaborted on a number of the designs.

In 1956, a book was published featuring the drawings and paintings of Edith and Rowland Hilder. Rowland also had his own books published: Starting with Watercolour and Painting Landscapes in Watercolour and the two volumes of his paintings under the titles Rowland Hilder’s England and Rowland Hilder Country..

After the Second World War, Rowland formed a small family business with his wife and father called The Heron Press which printed, amongst other things, greeting cards. They became known as “Hilderscapes” a term that Hilder himself disliked. In 1963 Rowland wanted to move away from his illustrative work and return to his first love, watercolour landscape painting and so he severed connections with the company.

Shoreham in Kent by Rowland Hilder

Shoreham in Kent by Rowland Hilder

When it comes to locations for his paintings Rowland Hilder considered Shoreham, a village and civil parish in the Sevenoaks District of Kent, England, located 5.2 miles north of Sevenoaks. and the Shoreham Valley, as his first love.

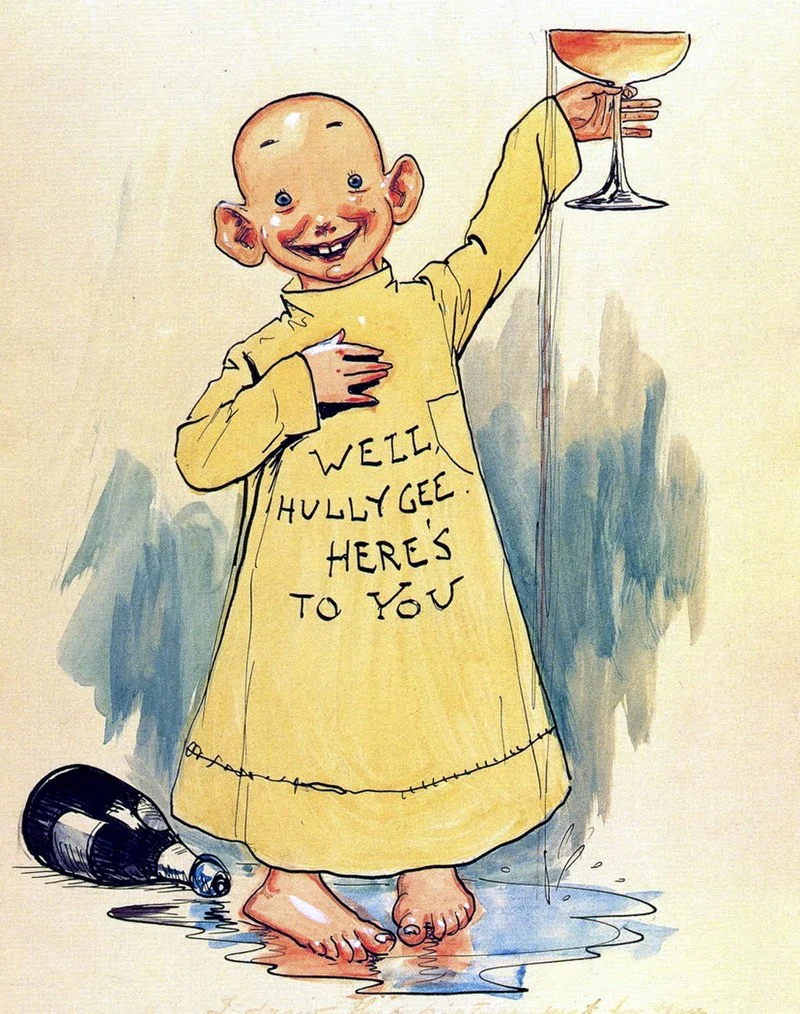

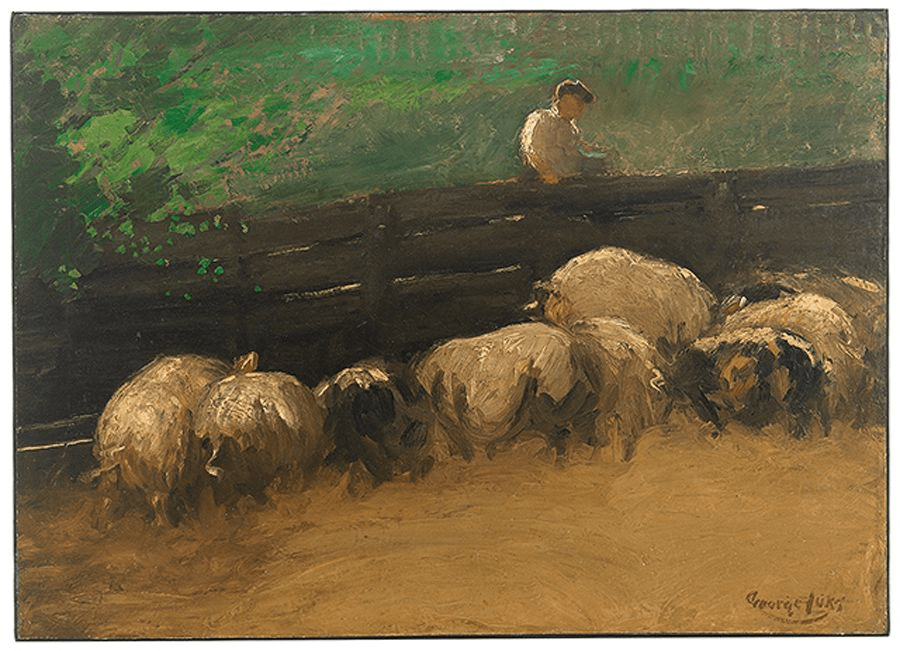

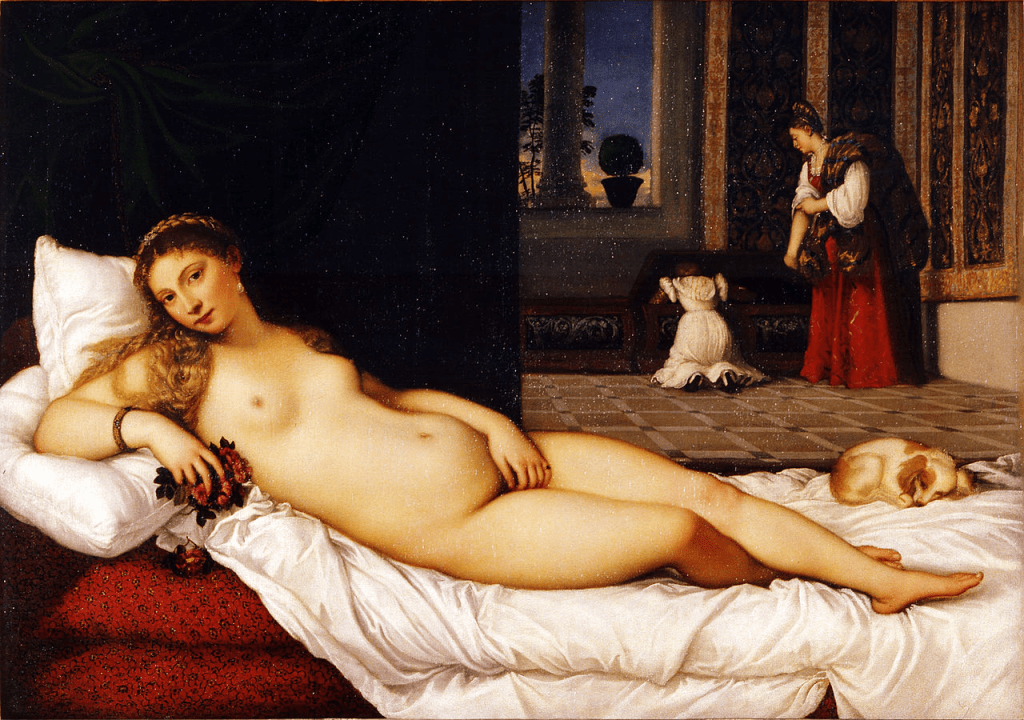

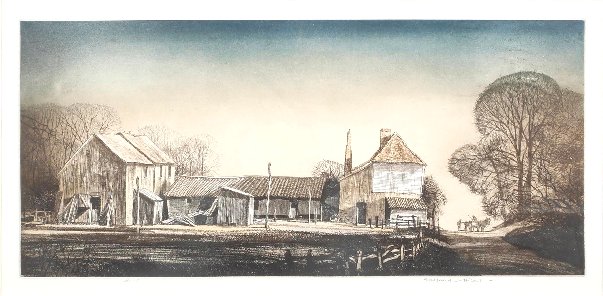

Samuel Palmer ‘s “Barn in a Valley, Sepham Farm”

It was also here in the 1820s that Samuel Palmer, a key figure in Romanticism in Britain, produced visionary pastoral paintings of that area. Hilder tells of how he came across Shoreham:

“…Some fellow students and I discovered Palmer together when we were at Goldsmiths’ College, so I went out to find Shoreham for myself, taking a camera with me. I photographed the farms, and oasts and walked the lanes. I discovered one of my photographs was of Sepham Barn, one of Palmer’s subjects. It had not changed in a hundred years. Later when I went back it had been knocked downand a new tin one was there in its place. I can’t bring myself to include that modern version in my paintings of Shoreham…”

The Lane, High Halstow by Rowland Hilder

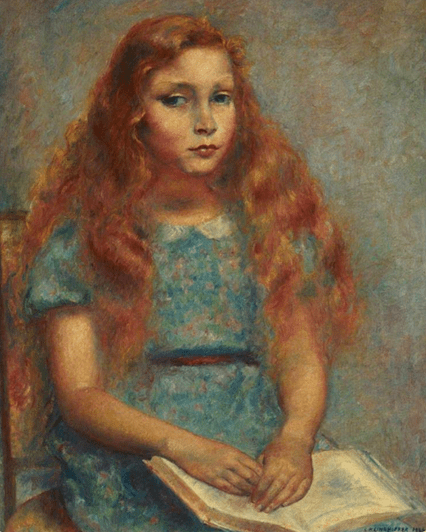

Twenty miles north-east of Shoreham lies the village of High Halstow and the surrounding area was the subject of Rowland Hilder’s studies for over fifty years. On one occasion Rowland and fellow Goldsmith student, Norman Hepple, during a sketching holiday, rented an old disused pub in the village. From the front windows they had a view of the neighbouring farm, which was situated in a lane which led to a bird sanctuary. Roland recalled the time:

“…We were invited by a keen bird watcher to join him in one of the hides, to watch a nest of baby herons. I disgraced myself by making an accidental noise, whereupon all the babies were simultaneously sick…”

Rowland Hilder’s sketch

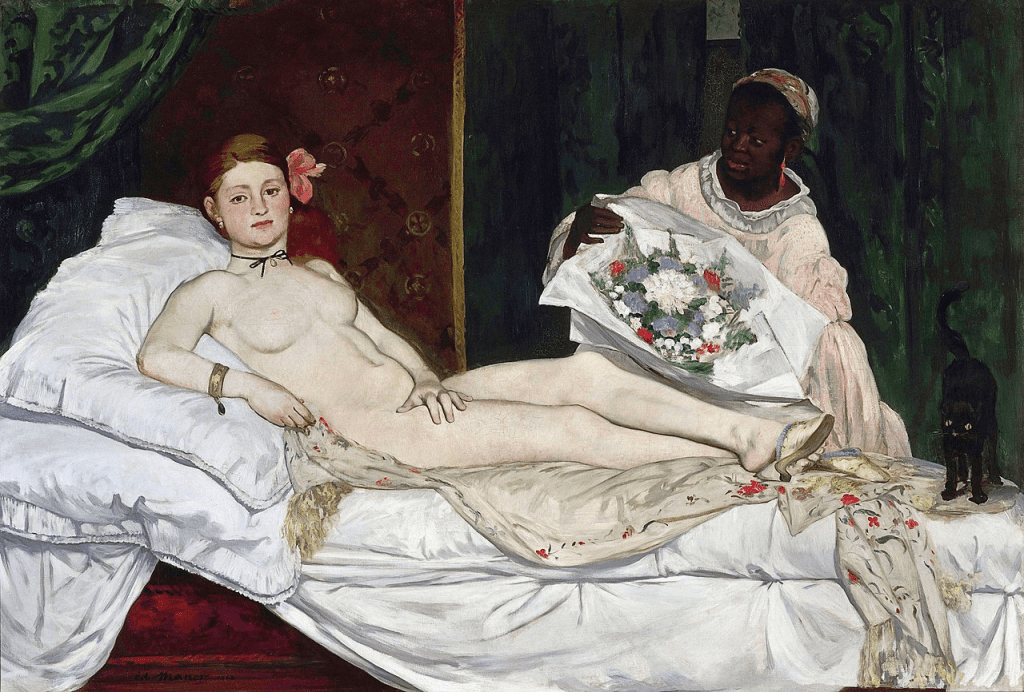

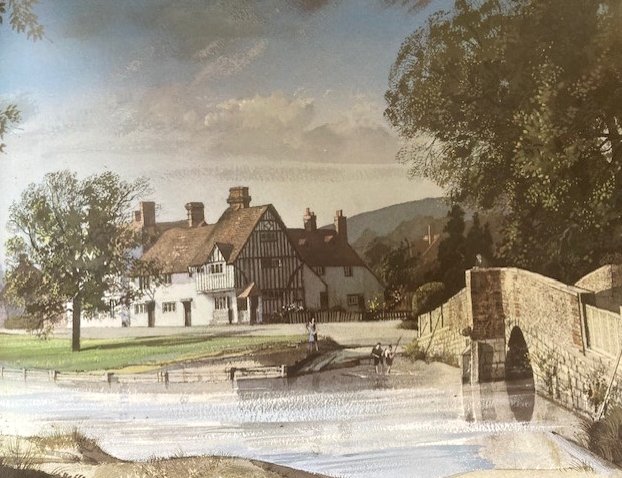

The Old Ford and Bridge, Eynsford by Watercolour by Rowland Hilder

Eynsford is a village and civil parish in the Sevenoaks District of Kent and is a few miles north of Shoreham. This area is undulating and has a large minority of woodland. This was also a place Hilder visited many times to sketch and very little has changed since his time. The bridge at Eynsford leads to a popular pub, the ruins of the local castle and many walks along the river Darent to Lullingstone bridge with its reconstituted Roman villa.

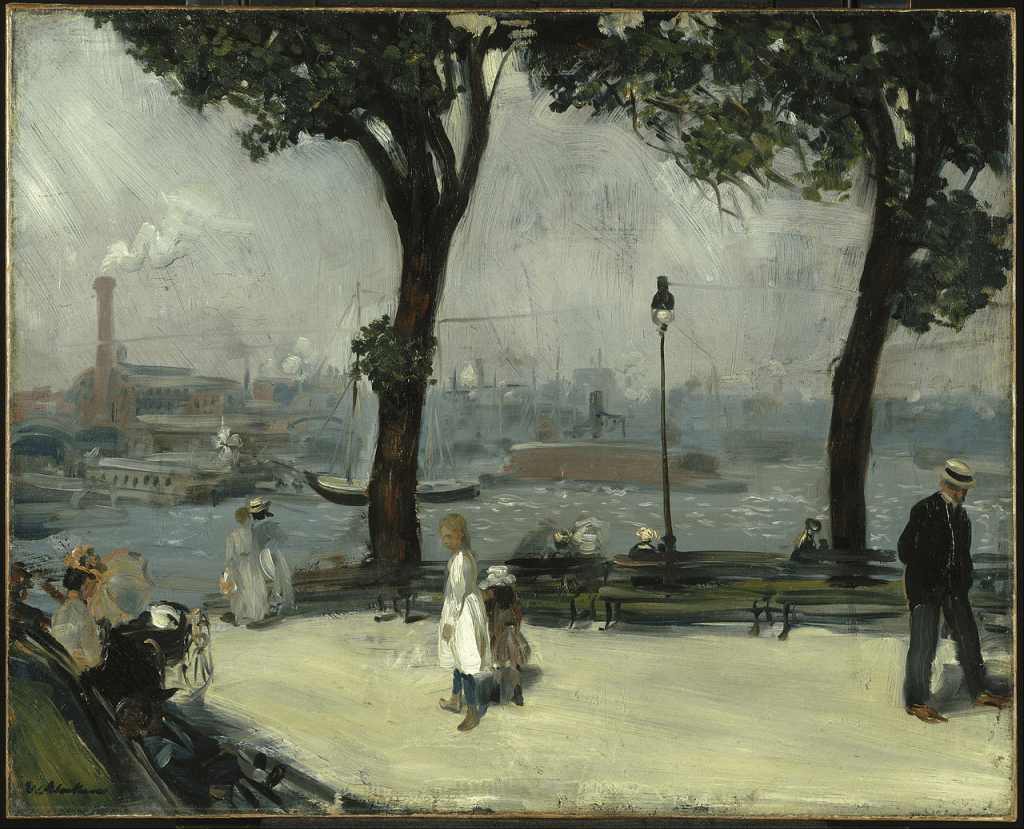

London Docklands by Rowland Hilder

Like his contemporaries, Claughton Pellew, John and Paul Nash, Edward Bawden and Eric Ravilious, Hilder shared their interests in depicting the countryside. They would explore themes of rural peace and harmony and rejected modernism. However, Pellew and Ravilious often depicted the clash between pastoral tranquillity and the rise of modernism whereas Hilder just concentrated on depictions of rural beauty whether it is bathed in sunshine or covered in snow and the by-gone aspects of farming practice.

First Snow by Rowland Hilder

Surprisingly Hilder was himself never taught watercolour. He honed the skills after his training, and he wrote several books on the subject. He also taught his skills at Farnham School of Art, and as professor of art at his alma mater, Goldsmith’s. In 1938 he was elected a member of the Royal Institute of Water Colours, and in 1964 he became president of the Institute. His work was included in the 1984 Hayward Gallery exhibition: The British Landscape 1920-50. Retrospective exhibition at the Woodlands Gallery in 1985 and Hilder was appointed OBE in 1986. He lived in London but retained a base at Shell Ness, a small coastal hamlet on the most easterly point of the Isle of Sheppey in the English county of Kent. Where he would carry out his marine painting. He continued to paint into his retirement and died in Greenwich on the 21st April 21st, 1993 two months before is eighty-eighth birthday.

In putting this blog together I was helped by information I found in the following websites: