……………………..Cecilia Beaux and her cousin May Whitlock had arrived in Paris in the last week of January 1888. The weather had been typical January weather – wet, cold, and thoroughly miserable, rarely catching a glimpse of the sun. Add to this their insalubrious and uncomfortable pension and the way they had to dress in warm but shabby winter clothes, it is possible that Cecilia’s dream of the French capital may have been wavering. However, she had her course at Académie Julian and numerous art galleries to visit which, for her, made life worth living. She revelled in her visits to the Salon not only viewing the paintings but also “people-watching” the visitors circulating the galleries. In her autobiography she recalls such a time with great excitement:

“…The Salon drew crowds of all kinds. To Vernissage [a preview of an art exhibition] flocked the elite of Paris, the aristocracy of Society, of the Stage, of Music, and Literature, as well as of the Plastic Arts: in other words, the French Crowd, always intelligent, always amused, always disputive. How new to me to see a group of forceful, middle-aged, or old men, masters in some field without doubt, stooping over a small picture, arguing with heated insistence, denouncing, eulogizing! Never had I seen assembled so many men of ‘parts’ — real men, I would have said — so absorbed, so oblivious, greeting each other warmly, and with absolutely no general curiosity; pausing a moment, with great deference, before some quiet lady, or obvious beauty, but really there through profound interest in contemporary art. I longed to get closer — not to meet them, but to hear their talk, their dispute about the supreme Subject…”

And later describes how she witnessed one special visitor to the Salon:

“…Into the gallery one day, as our obscure party moved about,- there entered a Personage; a charming figure, with a following of worshippers. The lady was dressed in black lace, strangely fashioned. Though she was small, her step and carriage, slow and gracious as she moved and spoke, were queenly. She was a dazzling blonde, somewhat restored and not beautiful, as one saw her nearer. The striking point in her costume — and there was but one — was that the upper part of her corsage, or yoke, was made entirely of fresh violets, bringing their perfume with them. Every one, artists and their friends, ceased their examination of the pictures, and openly gazed, murmuring their pride and joy in their idol, Sarah Bernhardt…”

All artists at one time or another make a choice about what medium they prefer to use but also what is to be their artistic style. Cecilia Beaux was no different. She had arrived in Paris at the beginning of 1881, the same year as the sixth Impressionist exhibitions. However, she was not seduced by Impressionism, writing:

“…The enthusiasm I felt for Monet’s iridescent pigments, his divided rays to reach the light of Nature by means of color only, left me with no desire to follow. Landscape, genre, I could pore over with no desire to take a white umbrella into the sun…”

For Cecilia, her Gods of art were the likes of Titian, Rembrandt, and Veronese, but she admitted there was even one thing that could seduce her away from art:

“…If there was anything that could have drawn me off my feet entirely, and divorced me from painting, it was to be found in the lower galleries of the Louvre, on some of the upper landings and among the isolated examples of Greek and Italian Renaissance sculptures. Mystery again. Sculpture for me was surrounded by the never really comprehended glamour of its creative act, as well as the absolute power of its beauty, on emotion…”

April was a welcome month for Cecilia as winter had almost been forgotten and the all the beauty of Springtime in Paris had arrived. With the improvement in the weather came the improvement in her disposition. She remembered the joy that this change in the weather brought to her spirit:

“…One morning in early April, we met, and saw, the first of Spring in Paris. All of youth, hope, and joy seemed to be in those shafts of sunshine, pouring through virgin leaf and violet shadow, and in the voices that called this and that from cleverly manipulated push-carts, heaped with flowers, vegetables, fruit, whose fresh moisture the sun touched with rainbow hues. Every French heart bounded with the hour’s happiness, and I knew that my heart was French, too…”

For Cecilia Beaux the summer of 1881 began with a new adventure. The academy had closed for the summer break and she and her fellow students were free to go off and paint. She and her American companions decided that the de rigeur destination for aspiring artists, especially Americans, was the artist colonies of Britany and specifically the coastal town of Concarneau. Cecilia’s intrepid group set of on a late June afternoon by train bound for Concarneau.

Because of the distance the party needed to break their journey and have an overnight stop-off at the town of Vitré famous for its twelfth century stone chateau built by the baron Robert I of Vitré, which the party visited before completing the second part of their journey. The party stayed at the little Hôtel de France. Cecilia Beaux had only sampled one French town, Paris, since her arrival in France and was amazed by the beauty of Vitré. She wrote:

“…It had been raining, I remember, and everything had all the color that moisture and a breaking sky, full of light, not sunshine, gives. When we looked up or down the steep little winding streets of mossy, grey, toppling houses, there was always a burning spot of red, a geranium in an upper window, or a white-coiffed woman, in a deep blue or green skirt, knitting in a doorway, coppers shining inside, or an old woman in sabots clattering down toward us over the rough stone pavement, or a tiny cherub in grown-up garments supping its bowl of pot au feu on a doorstep, and three children’s heads in a narrow window under the eaves, looking down at us…”

The party continued their onward journey to Concarneau and arrived the next evening. They took a cab to the upmarket hotel, Les Voyageurs where they had dinner with friends before setting off to find and secure some more modest accommodation. They eventually settled on a small propriété owned by Papa and Maman Valdinaire, who were local florists. Cecilia loved the property, describing it in her autobiography:

“…a house and garden with an eight- or nine-foot wall entirely enclosing the estate, which was about an acre, and was in a garden full of flowers only. The walls were covered with carefully trained Bruit, pears and apricots, and a number of small trees, perhaps for blossom only, cast flickering light and shade over the flower-beds…”

However, there were some drawbacks to their stay with the Valdinaires. The owners lived on the ground floor of the property and to gain access to the road or the garden they had to go through their accommodation which was also home to their chickens and their precious goat, which had freedom of the house but fortunately for them, couldn’t climb the stairs!! Also, according to Cecilia, the lady of the house “lacked character”. Cecilia described their accommodation:

“…The house was one room deep, and we were offered the two rooms on the second floor; also an attic for our kitchen. This had a large dormer window with lovely view toward the sea and a hosier for cooking on the hearth, really perfect in our eyes — but the fact that only one of the bedrooms was for the moment habitable was temporarily discouraging. They were at the top of the bare stairway, on — I called it — the second floor. There were windows on both sides, the sunny ones looking on the garden and within easy sight of the pigeons, and the garden, which was, with all its varied charms, to be our painting ground and studio…”

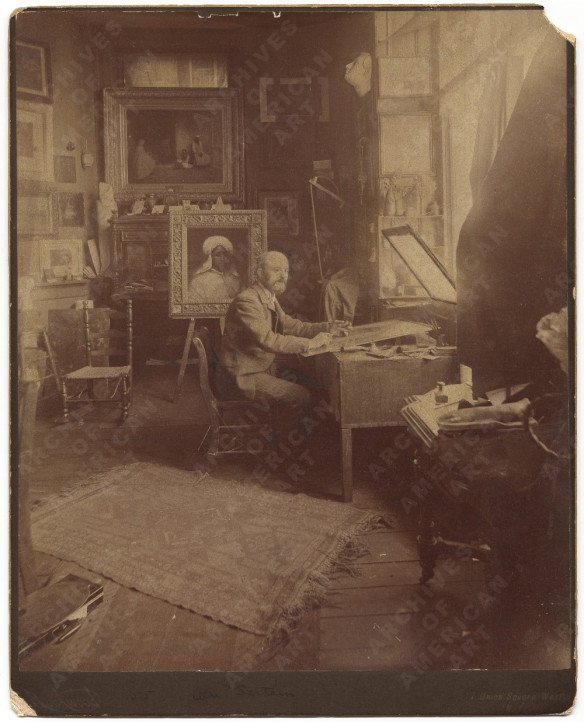

One of the main reasons for Cecilia choosing Concarneau that summer was that two other important painters from Pennsylvania had studios in the area. They were Thomas Alexander Harrison and Charles “Shorty” Lasar. Harrison was mainly a marine painter and one of his most famous works was one he completed in 1885, entitled The Wave, which depicts waves rolling in on the beach. His mastery of light and colour in this painting is spectacular.

One of his “non-marine” works, In Arcadia, was exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1885 and it received “an honourable mention” and it was to be the first of many awards Harrison received for his artistic works. The painting is now housed in the Musée d’Orsay.

Cecilia completed a portrait of T Alexander Harrison in 1888, whilst she was at Concarneau. Harrison was pleased with the completed work and commented about Cecilia’s painterly stating:

“…she had the “right stuff” to become a serious painter, the stuff that digs and thinks and will not be satisfied and is never weary of the effort of painting nor counts the cost…”

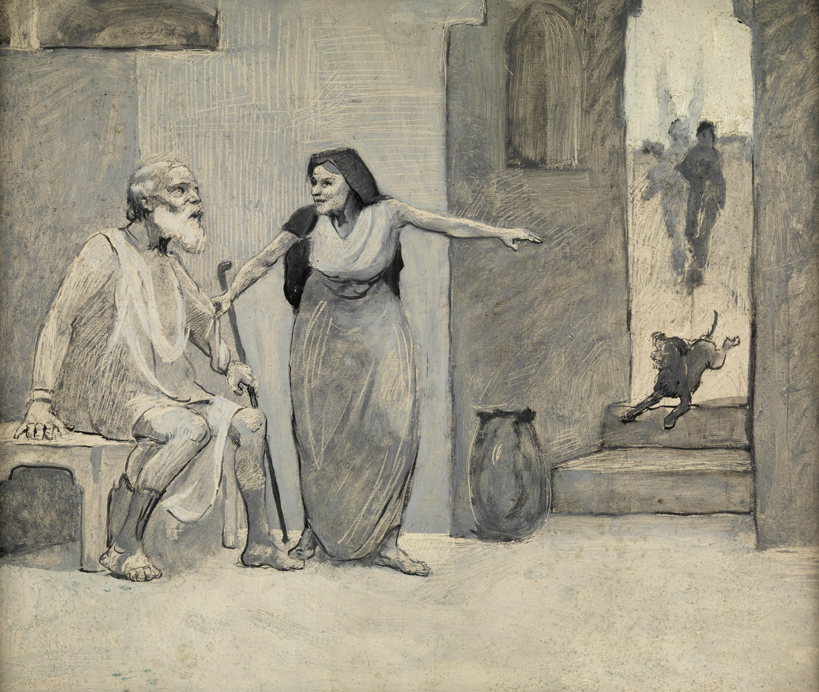

Whilst at Concarneau Cecilia Beaux complete several grisaille paintings. Grisaille paintings are those done entirely in shades of grey or another neutral greyish colour. The set of grisailles she completed all depicted biblical themes and they were a distinct, if not fleeting, departure from her beloved portraiture. One such work was entitled Tobias Returning to His Family and is based on an Old Testament story about the blind man Tobit and his son, Tobias’ return home with his dog and how he cured his father’s blindness. In the Old Testament Book of Tobias 11:9 it describes the coming of Tobias preceded by the delighted dog:

“…and coming as if he had brought the news, shewed his joy by his fawning and wagging his tail…”

In the depiction we see Tobias’ dog bounding through the central doorway ahead of his master, “announcing” the son’s arrival.

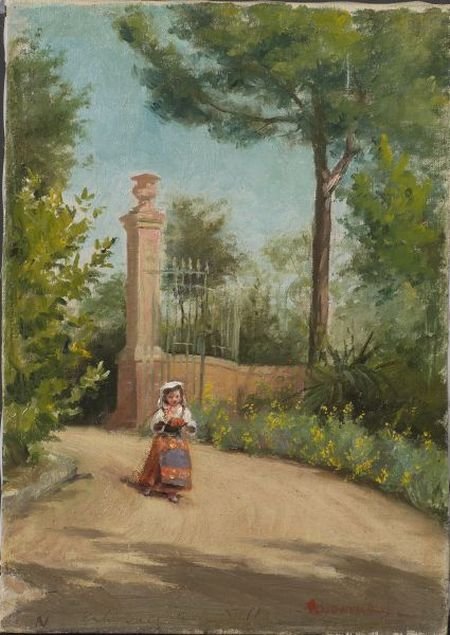

Whilst in Concarneau that summer, Cecilia Beaux also unusually strayed away from her usual portraiture to complete a couple of landscape works. One such work was entitled Landscape with a Farm Building.

However, by far the most memorable works produced by Cecilia whilst in Concarneau was her 1888 painting entitled Twilight Confidences and the number of studies which led to the finished work, all of which are held at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art in Philadelphia and the completed work was exhibited at their 1890 Annual Exhibition. This finished work is looked upon as her first foray into plein air painting. It is a juxtaposition of the two figures and the seascape and all are lit by the light of the setting sun. Cecilia recalled the sketches and painting:

“…I attempted two life-size heads, at dusk, on the beach; two girls of the merely robust type in conference or gossip — the tones of coiffe and col mingling with the pale blue, rose, and celadon of the evening sky…”

The coiffe is the decorative headdress and col is the decorative collar associated with Brittany.

In his 1983 book, Americans in Brittany and Normandy 1860-1910, David Sellin quotes Cecilia Beaux’s thoughts about the preparatory stage of this work:

“…if I succeed with my two heads it will be the opening of a new era for me, that of working from pochades [sketches] for large simple outdoor effects. I can see that the strongest part of what gift I have is my memory of impressions…”

Above is one of the many preparatory sketches held by the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art is a small (14 x 15cms) oil on cardboard grisaille sketch.

Their summer sojourn in Concarneau eventually ended and Cecilia and her friends, with the help of their landlady, Madame Valdinaire, decided to host a going-away party for their friends. On the menu was to be chicken which delighted Cecilia until she was told by her hostess that she must choisi le poulet. She remembered the incident well, writing:

“…It was a dark night in October. The chickens had retired early, and it was my lot to follow Madame V. and her lantern to the sleeping-quarters of her brood. Of course they had heard us coming, and when the door was opened and the lantern shone upon a row of dusky, perching bundles of feathers, a dilated, circular eye scintillated with terror in each sideways-turned head. A few sleepy, guttural croakings came from the back row, but those in front were silent and fixed. Madame Valdinaire, with cruel liberality, asked me if I preferred the brown or the speckled, or both, and seized one at random by its yellow legs, holding it upside down for me to palper [feel] its shrinking body, the one eye always turned up and fixed in the struggling bunch of squawks. Here I turned and fled, bidding Madame V. choisir herself, and stumbled into the house and up to our room, where my cousin sat placidly writing a letter…”

Cecilia Beaux and her companions left Concarneau in October 1888 and set off on what was to be a six-week trip around Europe by train. They went through Switzerland and crossed the Alps via the St Gothard Pass on their way to Venice, where they stayed for six days. From there they journeyed to Florence, stopping in the Tuscan city for six days. Sadly for Cecilia most of those days she was laid low with an illness. They then went across to France and called at Avignon and Nimes, the home town of Cecilia’s late father who had died in 1874. The journey ended back in Paris in December 1888 and Cecilia was proud of how frugal she had been during this six-week adventure saying:

“…It may be of passing interest to present-day tourists to know that in our six weeks’ journey we were only by way of second- and third-class, by train; and pension, never hotel; we spent just $107 apiece and had no sense of being penurious…”

……………………………….to be continued

Most of the information for the blogs featuring Cecilia Beaux came from two books:

Background with Figures, the autobiography of Cecilia Beaux

Family Portrait by Catherine Drinker Bowen

and the e-book:

Out of the Background: Cecilia Beaux and the Art of Portraiture by Tara Leigh Tappert.

Extracts from letters to and from Cecilia Beaux came from The Beaux Papers held at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art

Information also came from the blog, American Girls Art Club In Paris. . . and Beyond, featuring Cecilia Beaux was also very informative and is a great blog, well worth visiting on a regular basis.:

https://americangirlsartclubinparis.com/tag/catherine-ann-drinker/

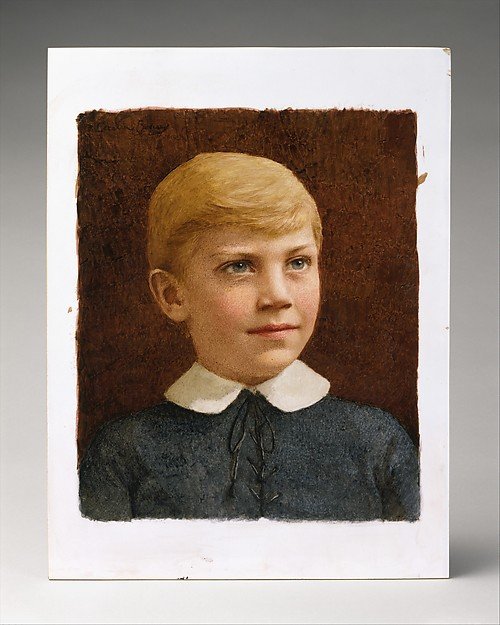

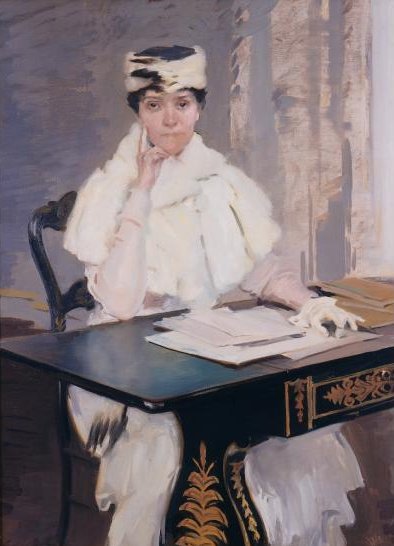

The haunting facial expression of the sitter with her piercing stare makes for a beautiful study.

The haunting facial expression of the sitter with her piercing stare makes for a beautiful study.