Somebody once said that the only way to enjoy the sight of snow is when looking at a postcard or a painting. I have spent a number of Christmas Days in hot climes such as Karachi and Melbourne and know that Christmas is not Christmas without snow. So for this Christmas blog I want to look at some of the beautiful winter landscapes created by famous and not-so-famous artists to remind me of a snowy Christmas, many of which have featured in earlier blogs.

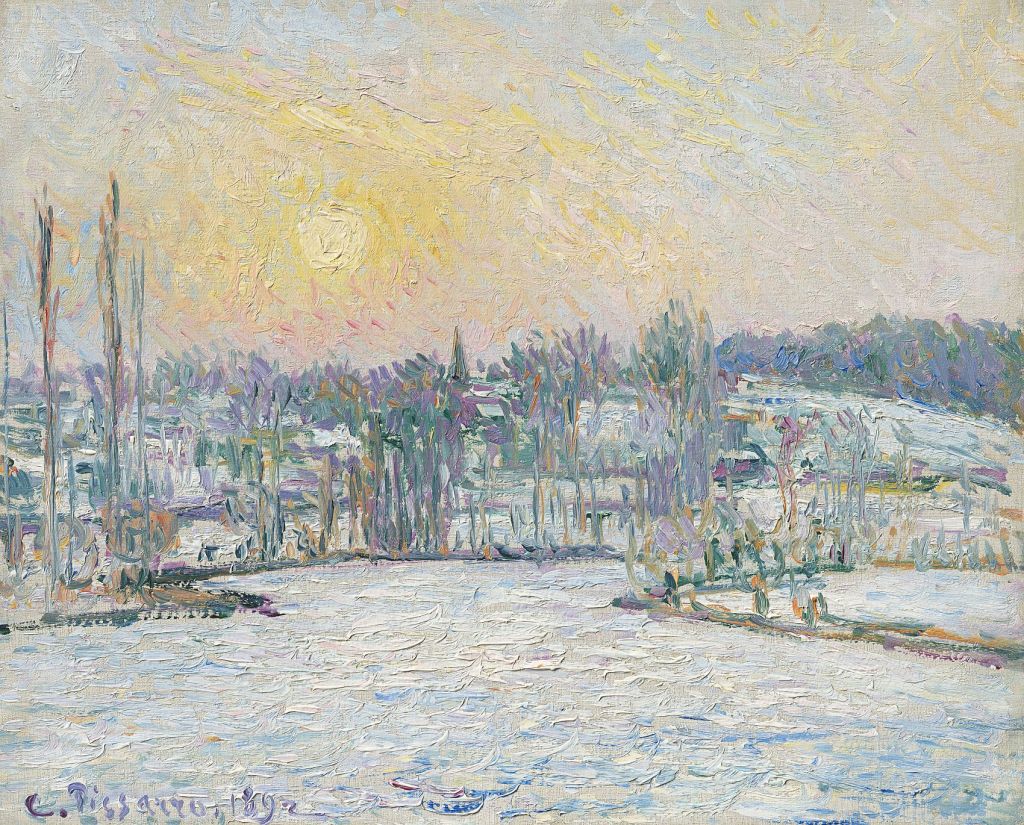

View of Bazincourt, Snow Effect Sunset by Camille Pissarro (1892)

Camille Pissarro depicted the small town of Bazincourt-sur-Epte at all times of the day, and in all seasons, in a number of his paintings. In 1892 he completed his work entitled View of Bazincourt, Snow Effect, Sunset. In this Impressionistic-style painting we can see how Pissarro has managed to infuse a warmth to the scene by his use of violet for the trees and the way the sun has illuminated the clouds.

Snow Scene at Argenteuil by Claude Monet (1875)

The great Claude Monet, known for his lily ponds at Givenchy, also painted a number of winter landscapes. The first one I am looking at is his work entitled Snow Scene at Argenteuil. Monet and his family moved to Argenteuil a small Parisian suburb twelve kilometres north-west of the heart of the French capital and was accessible from central Paris with a short train ride. Monet painted many scenes in and around Argenteuil featuring the riverbanks of the Seine, the railway bridge which straddles the French river, which often featuring a steam train chugging across the structure. The painting I have chosen was one of eighteen that Monet completed which depicted the snowy winter of 1874/5. It is a depiction of the Boulevard Saint-Denis, near Monet’s home. It looks towards its junction with the rue de la Voie des Bans, with the River Seine beyond. The figures we see in the painting are plodding along the road and it could be that they are making their way to or from the nearby railway station which lies behind the artist. The station would have been used by holiday makers and commuters on their way from Paris. The snowy road surface has dark brown furrows made by passing carts and as we follow them we can see the town in the background. This painting was one of the largest (71 x 91cms) snowscapes that Monet completed but does not have some of the finer details in Monet’s smaller winter paintings.

La Pie (The Magpie) by Claude Monet (1869)

My favourite winter painting by Monet was completed in 1869, six years before the Argenteuil work. He painted it during the winter of 1868–1869 whilst he and his girlfriend, Camille Doncieux were living near the commune of Étretat in Normandy in a house Monet’s patron, Louis Joachim Gaudibert, had arranged for them. This is Monet’s largest (89 x 130cms) winter painting. The painting depicts a solitary magpie which has alighted on a gate which has been fitted between parts of a wattle fence. Sunlight falls upon freshly fallen snow producing blue shadows. This “blue shadow” phenomenon later became associated with the Impressionist movement artists. Monet and those Impressionists exploited the use of coloured shadows to symbolise the actual, changing circumstances of light and shadow as witnessed in nature, and by so doing, they defied the academic convention of painting shadows black. However all were not pleased with this new concept which led to its rejection by the Paris Salon of 1869. However present art historians today believe that The Magpie is one of Monet’s best snowscape paintings. The painting was acquired by the Musée d’Orsay in 1984 and is considered one of the most popular paintings in their permanent collection.

Snow at Louveciennes by Alfred Sisley (1874)

It is believed that due to a series of severe winters in France in the 1870s it contributed to a sudden increase in the number of winter landscapes produced by Impressionists. My next painting I am showcasing is one created by Alfred Sisley in 1874, entitled Snow at Louveciennes. Before us we see a picturesque scene of stillness set in early winter’s morning in Louveciennes, a small village in the Île-de-France region in north-central France, located in the western suburbs of Paris, between Versailles and Saint-Germain-en-Laye. Sisley depicts the sky in white, crisp blue, and grey hues. His use of perspective guides the viewer along a winding road which vanishes into the background. The buildings in the paintings are covered with snow and we see a lone woman holding an umbrella strolling along the pathway, which has trees on either side. The artist is willing us to take a walk with the woman as she heads towards the village. Sisley was entranced by views of the countryside during the winter months. In fact, unlike most of us who dreaded heavy snowfall Sisley was inspired by what he saw and was especially attracted by how the variations in light came into play in snow scenes.

Effect of Snow on Petit-Montrouge by Manet (1870)

The oil on canvas painting entitled Effect of Snow on Petit-Montrouge was painted by Edouard Manet and depicts a winter view of Petit-Montrouge, in the 14th Arondissment of Paris. Manet completed the work in 1870 whilst he was serving in the National Guard during the 1870–71 Siege of Paris in the Franco-Prussian War. There was no hint of the war, no heroic view of the battle or the bloody fighting, which was raging around the French capital, as often seen in the work of other artists’ paintings of the time. This painting, although a snowy scene, is awash with shades of brown and black giving it a dark and foreboding ambience which could well be because the way Manet was feeling about the course of the ongoing war. During this time Manet wrote to his wife:

“…My soldier’s knapsack serves…to hold everything necessary for painting. I shall soon start some sketches from life. They will be souvenirs that will one day have value…”

The painting depicts a view of the church of Saint-Pierre at Petit-Montrouge, and it is inscribed:

“…â mon ami H. Charlet 28 Xbre 1870. Charlet…”

Charlet is thought to have been a comrade in the National Guard. The dark image reflects Manet’s loss of hope regarding the impending military defeat and his deep loneliness, the deprivation and his bouts of depression he suffered during this time. It is one of the few landscapes in Manet’s oeuvre and is one of Manet’s first plein air paintings. Today it is in the collection of the National Museum Cardiff.

The Rooks have returned by Alexi Savrasov (1871)

Having looked at a painting by Monet featuring a black coloured bird against the white of the snow I had to give you one of my favourite works of art and this too features black birds and snow. It is not quite a winter scene more “a coming of Spring motif”. It is Alexi Savrasov’s painting entitled The Rooks have Returned, which I saw at the Tretyakov Gallery when I was in Moscow. Savrasov was one of the most important, some would say, the most important of all the 19th century Russian landscape painters, and he was deemed the creator of the “lyrical landscape style”. It is Savrasov’s most famous painting, and the painting is considered by many critics as being the high point in Savrasov’s artistic career. The depiction witnesses the coming of spring as signalled by the return of the rooks. The work is testament to Savrasov’s love for the rural Russian landscape, and he was very influenced by John Constable. The depiction we see before us is a simple, and depicts the somewhat inconsequential occurrence of birds returning home in spring to an extremely unpretentious landscape, but it was Savrasov’s way of communicating the change of seasons from Winter to Spring. Simple and yet beautiful. The great Russian painter, the classical landscape painter, Isaac Levitan commented about its simplicity saying that although the painting was very simple, beneath its simplicity there is the tender artist’s soul, who loves nature and values it. The painting enhanced Savrasov’s reputation as a landscape painter and it contributed to the success of the first exhibition organized by the Peredvizhniki.

Queue to a Resrvoir by Vasily Perov (1865)

Another depiction of a harsh winter and its effect on the people is Vasily Perov’s work entitled Queue to a Reservoir depicting people in freezing conditions to get themselves some water. It is a reminder of what is happening even nowadays.

Winter Landscape by Caspar David Friedrich (1811) Staatliches Museum, Schwerin.

If your taste in winter landscape paintings is not so much for aesthetic beauty but for depictions that are full of atmosphere then you should look no further than the winter scenes painted by the great German artist, Caspar David Friedrich. His two Winter Landscape paintings of 1811 relate a poignant story. One of the works is housed in the Staatliches Museum, Schwerin whilst the other is in the National Gallery, London. In the Schwerin picture, we observe a tiny figure, leaning on a crutch. He gazes out on a deserted snow-covered landscape. The sky is coloured grey/black adding to the ominous feel to the work. The man meanders between dead or dying oak trees, and the stumps of felled trees. It is a depiction of total barrenness and this bleakness adds to the feeling of hopelessness. Life for him could not get any worse.

Winter Landscape with Church by Caspar David Friedrich (c.1811). National Gallery London.

However the National Gallery painting, a companion piece to the one in Schwerin, offers us a glimmer of hope for the man. This painting signifies the hope of resurrection through Christian faith. Look carefully at the snow in this work and you will see shoots of grass pushing through the snow and the evergreen trees and faint pink glow of approaching dawn affirm its message of renewal and rebirth. It is a fine example of Friedrich’s use of landscape painting as a vehicle for religious feeling and personal symbolism. As he stated, his aim was not ‘the faithful representation of air, water, rocks and trees … but the reflection of [the artist’s] soul and emotion in these objects.’

Man praying and abandoned crutches

The painting depicts a man, an invalid, who, in the Schwerin painting, we saw wandering helplessly in the snow, has now thrown away his crutches and lies against a large boulder as he prays in front of a shining crucifix protected by three fir trees, symbolising the Christian Trinity. In the background we see the silhouette of a German Gothic cathedral which is partially covered by a grey mist. Unlike the hopelessness of the man’s situation in the first painting, Friedrich has instilled a sense of hope of a new life through Christian faith.

Hunters in the Snow by Pieter Bruehel the Elder (1565)

No compilation of winter landscape paintings would be complete without the inclusion of such works by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. In 1565 he completed his oil on wood painting entitled The Hunters in the Snow which is also referred to as The Return of the Hunters. The work is part of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, Austria. It is one of his great genre painting scene with an aeriel viewpoint of a winter’s scene. The painting was one of a twelve-work series depicting different times of the year and this one is set in the depths of winter during the months of December/January. Before us we observe a wintry scene and in the left foreground, we see three hunters who are returning from an outing along with their dogs. They are heading down a snow-covered slope towards a small village. Looking at the men trudging resignedly home with their dogs it appears not to have been a successful hunt with only one of the men carrying over his shoulder one dead fox, the fruit of their labour. As if to taunt them, there are footprints of rabbits around them, which they failed to ensnare. It is a cold overcast winters day with little or no wind as we can see by the lack of movement of the wood smoke. Bruegel has used muted white and grey colours in this composition to give it an air of melancholy. On the leafless trees we see crows perched on the bare branches. The setting is a flat-bottomed valley through which a river meanders.

In the background we see an idealised landscape depicting jagged mountain summits which do not exist in Bruegel’s homeland but which would have been seen with him during his time in the Alps. At the bottom right of the painting we see the large wheel of a watermill which has been frozen stiff. Below on the frozen lake people are ice skating. To the returning hunter’s left we can see an inn with villagers preparing a roaring fire in preparation of roasting a pig. The sign on inn is hanging askew. The image on the sign depicts a stag named Saint Hubertus, who is the patron saint of hunters. The words are in Dutch, Dit is Guden Hert, which means in English “This is the Golden Deer”.

The Census at Bethlehem by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1566)

Another winter painting by Bruegel the Elder is his 1566 work entitled The Census at Bethlehem, also known as The Numbering at Bethlehem. It depicts the collecting of names of the villagers so as to enforce a tax collecting regime. Bruegel would have painted this following the harsh winter of 1565. In this work Bruegel depicts a scene which pre-dates the Nativity and the birth of Christ. The scene before us takes inspiration from the Gospel of Luke, chapter 2, verses 1 to 5.

“…In those days a decree went out from Emperor Augustus that all the world should be registered in their own towns. Joseph also went from the town of Nazareth to the city of David called Bethlehem … with Mary with whom he was engaged and who was expecting a child…”

Although the story behind the painting is set in the Holy Land, Bruegel Bruegel combines this biblical narrative with life during his own time. He has set his work in a Flemish village in winter at sunset with the ruined castle in the right-hand side of the background being based on the towers and gates of Amsterdam. People are gathered at a building on the left registering their details. We can just about make out the Habsburg double-headed eagle on a sign on the building. Villagers are streaming towards the census point, two of whom are Joseph and the Virgin Mary, who is with child, riding on a donkey. People are mingling in the cold, and we see happy children playing with toys on the ice and having snowball fights. There is the strange sight of a spoked wheel at the centre of the painting and this has occasionally be deemed to symbolise the wheel of fortune. To the right, a man in a small hut is shown holding a clapper, a warning to keep away from leprosy. Leprosy was endemic in that part of Europe when the painting was created. There is a begging bowl in front of the hut. In the background, men drink at a makeshift bar, and in the distance we see a well-kept church and a crumbling castle.

Bruegel once again treats a biblical story, in this case, the Census of Quirinius, as a contemporary event. He wants to liken the harsh events of the Roman occupation with the severity of the Spanish administration, who at Bruegel’s time, were ruling the southern Netherlands. It is also thought that Bruegel was condemning the bureaucracy he was having to fight on a daily basis.

Census at Bethlehem by Pieter Bruegel the Younger (c.1590)

Pieter Brueghel the Elder’s son Pieter Bruegel the Younger and his studio made dozens of copies of his father’s painting after he died in 1569. One, thought to be completed before 1600, was sold at auction for $10 million in 2013. One other copy, dated from 1610, is also at Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels.

Love of Winter by George Bellows (1914)

I will almost end this compilation of winter scenes by highlighting two works completed by the distinguished American artist, George Bellows. George Bellows was born in Columbus, Ohio in 1882 and after passing through the various school years arrived at Ohio State University at the age of nineteen. It was here that his sporting prowess came to the fore and at one time it was thought that he may take up baseball professionally. During his time at the university, he funded himself by working as a commercial illustrator. However, Bellows had one aim in life and that was to become an artist, so much so, that he quit the university just before he was due to graduate and moved to New York to study art.

He enrolled in the New York School of Art and became a student of Robert Henri. It was through Henri that Bellows came into contact with a group of artists known as The Eight and later became part of The Ashcan School. The Eight was a group of artists whose fame derives from, and for what they will always be remembered for, their one and only joint exhibition in 1908 at the Macbeth Gallery in New York. The exhibition was a sensation and it is now looked upon as one of the most important events in the development of twentieth-century American art.

It is said that Bellows wrote to a friend in January 1914:

“…There has been none of my favourite snow. I must always paint the snow at least once a year.”

Unknown to him these were prophetic words as on February 13th 1914 New York City was hit by a major blizzard and it was this occurrence which led to Bellows painting his famous 1914 work entitled Love of Winter. The whole winter scene was intensified by Bellows with his use of bright reds, yellows, and greens and the feel of movement in the painting is achieved by his broad slashing brushstrokes. The enthusiastic group of skaters and onlookers of differing ages, differing social classes echoes the diverse populations who appreciated the public parks and the leisure activities on offer to them in early 20th-century New York City.

Blue Snow, The Battery by George Bellows (1910)

His other snow scene I wanted to show you is entitled Blue Snow, The Battery which he completed in 1910. The setting for the painting is Battery Park which lies adjacent to the financial district of Manhattan. There is a breathtaking beauty about this work of art. His imaginative and powerful use of blue energizes the scene of the southern tip of Manhattan. Bellows painted a number of scenes with New York City under snowfall and as with this work it is amazing how he has developed a strong sense of light and visual texture contrasting the white and blue of the snow and the dark grimy outline of the old buildings. It is a beautiful strong composition which is normally housed at the Columbus Museum of Art.

Winter Landscape by Wassily Kandinsky (1909)

The inclusion of a blue tint in the depiction of the snow gave Bellows’ winter scene a colder ambience. Snow is white but a tinge of blue adds to its portrayal but what about other colours for snow? Wassily Kandinsky’s painting Winter Landscape is one of the works in which the individualities of the artist, who was one of the founders of abstract art, are shown in the full extent. The motif of thin black trunks is often used by Kandinsky in his landscapes. Bright colouring with predominant pink, yellow, blue and black is based on immediate visual impressions: the artist seeks to convey various light effects in the snow illuminated by the setting sun. Kandinsky explained his choice of colours:

“…Colour provokes a psychic vibration. Colour hides a power still unknown but real, which acts on every part of the human body…”

Your thoughts ?

I hope you enjoy this over-long blog but it is holiday time and hopefully you have plenty of time to read it. I end by wishing you a Happy Hanukkah, A Happy Christmas and a peaceful and prosperous New Year.

In the middle ground we see the solitary figure of Christ on a rocky mound approaching the gathering. Behind him in the background is a wide plain and the distant mountains. His figure is small in comparison to the others but nevertheless stands out because of it being a lone figure. In the foreground of the picture there are a number of male figures of varying ages, some of whom are already undressed waiting to be baptised.

In the middle ground we see the solitary figure of Christ on a rocky mound approaching the gathering. Behind him in the background is a wide plain and the distant mountains. His figure is small in comparison to the others but nevertheless stands out because of it being a lone figure. In the foreground of the picture there are a number of male figures of varying ages, some of whom are already undressed waiting to be baptised.