1830-1890

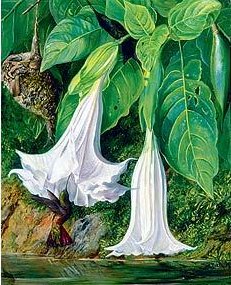

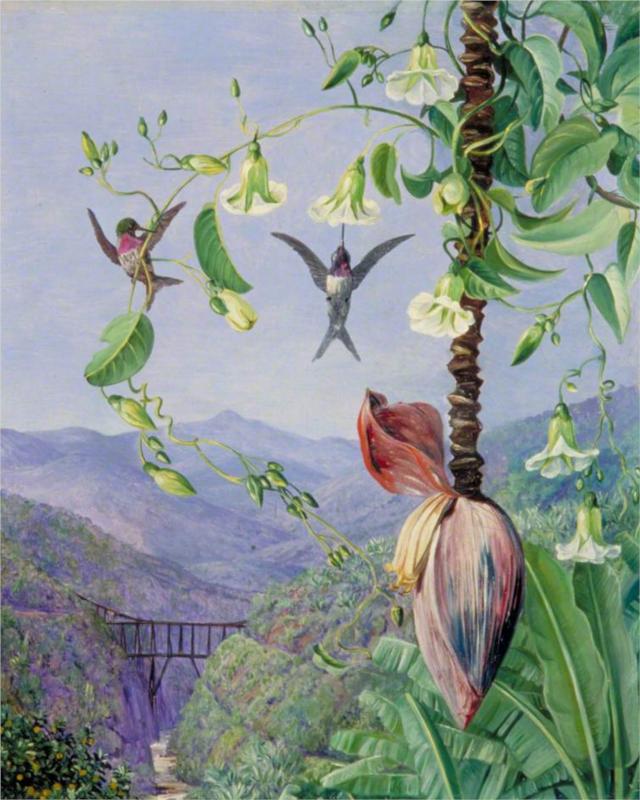

The artist I want to look at today could, I suppose, be labelled simply as a floral painter but in fact because of her desire for accuracy in floral detail she is often referred to as a botanical painter. Even today, in the age of photography, botanical art still thrives and with so much destruction of habitats around the world, which nurtured rare flora, the necessity to record such species in detail is of paramount importance. My featured artist today is the Victorian artist Marianne North.

Marianne North was born at Hastings Lodge in Hastings, England on October 24th 1830. Her father Frederick North, an Old Harovian, was a wealthy landowner, local magistrate and, on a number of occasions, a Liberal Member of Parliament for Hastings. His wife Janet (née Marjoribanks), was the daughter of Sir John Marjoribanks M.P., 1st Baronet of Lees in the County of Berwick. She had been widowed when her first husband Robert Shuttleworth of Gawthorpe Hall in Lancashire died in a coaching accident 1818. She and her first husband had a daughter, Janet Shuttleworth. Marianne North came from a long line of nobility and many of her ancestors’ portraits hung in the family dining room. She was devoted to her father and in her autobiography, A Vision of Eden, she wrote of him:

“…My first recollections relate to my father. He was from first to Last the one idol and friend of my life…”

Marianne had an elder brother, Charles and a younger sister, Catherine. It is believed that she did not receive any formal education, except for a short period in a school in Norwich, which she hated. Marianne was adamant that she taught herself all that was to be learnt, writing in her autobiography:

“…Walter Scott or Shakespeare gave me their versions of history, and Robinson Crusoe and some other old books my ideas of geography…”

However the status and wealth of her father ensured that his children were well educated and often had the opportunity to mix with artists and musicians. Marianne was said to have had a penchant for singing and as a child was given vocal lessons by Charlotte Helen Sainton-Dolby, the well-known English contralto, composer and singing teacher. Unfortunately as a teenager her singing voice gave way and she began to concentrate on her other love – drawing and painting. Life was good for Marianne. As a young teenager, she had basked in a life of prosperity. It was a privileged life. Winters were spent at their Notting Hill house in London. In the spring, they would move back to their large family home in Hastings. During the summer months she and her family would either spend time on their farmhouse in Rougham, Norfolk, which had once been the laundry of Rougham Hall, once owned by her ancestors. Alternatively, they would stay at Gawthorpe Hall in Lancashire which had been inherited by Marianne’s step-sister, Janet. In the late summer of 1847 Marianne’s father took his family on a European tour which lasted almost three years. Throughout this time Marianne studied flower painting, botany, and music. On arrival back to London Marianne wanted to continue with her love of drawing and painting and it was arranged for her have some lessons in flower painting from a Dutch painter, Miss van Fowinkel and the English flower painter, Valentine Bartholemew, who had held the position of Flower Painter in Ordinary to the Queen from 1849 until his death thirty years later.

Marianne’s mother, Janet, who had increasingly become an invalid, died in January 1855. The relationship between mother and daughter was nowhere as strong as the one between her and her father. Marianne talked about her mother in her autobiography and commented:

“…On the 17th of January 1855 my mother died. Her end had come gradually; for many weeks we felt it was coming. She did not suffer, but enjoyed nothing, and her life was a dreary one. She made me promise never to leave my father…”

With her mother gone, Marianne, aged twenty-four, took on the role as the lady of the house, looking after her father and the running of the household. Her father, who had been the Liberal MP for Hastings on a number of occasions, would during the parliamentary recess take his two daughters off on long trips around Europe. One of their favourite destinations was the valleys around the southern slopes of Mont Blanc and Monta Rosa. By this time Marianne’s brother Charles had married and his father had given him the old house in Rougham. Marianne’s sister Catherine had married in 1864 and her father, Frederick North, narrowly lost his Hastings parliamentary seat by just nine votes at the General Election in July 1865 and this gave him the opportunity to set off on another voyage of discovery with Marianne travelling through Europe and the Mediterranean isles of Corfu and Cyprus before reaching Syria and Egypt.

Three years after his defeat in the General Election Frederick North was re-elected as MP for Hastings in 1868. Marianne’s father was sixty-eight years old and his health had begun to deteriorate but this did not stop him from taking a holiday to Southern Germany with Marianne. However during their Bavarian sojourn, he became ill and Marianne was advised to take him back home to Hastings, which she did. Frederick North died on October 29th. Marianne was devastated for not only had she lost her father, she had lost her greatest friend. She recalled his death in her autobiography, writing:

“…The last words in his mouth were, ‘Come and give me a kiss, Pop, I am only going to sleep’. He never woke again and left me indeed alone…”

She recalled how much her father had meant to her and one can feel her deep sorrow. She wrote:

“…For nearly forty years he had been my one friend and companion, and now I had to learn to live without him, and to fill up my life with other interests as I best might. I wished to be alone, I could not bear to talk of him or anything else…”

Marianne North carried on with her two great loves, travelling and painting the flora she saw during those voyages of discovery. In July 1871 she set off on a long journey which would last over two years. She arrived in Canada, travelled on to the United States, and later the Caribbean island of Jamaica. From there, in 1872, she journeyed to Brazil where she spent much of her time drawing in a remote forest hut. She eventually returned to England in September 1873. Throughout her time on her travels she would be constantly sketching the flora of the area and the landscapes.

In the spring of 1875 she was once again off on her travels. This time she visited Tenerife, and later that year started her first round-the-world trip taking in the west coast of America, Japan, Borneo, Java, and Ceylon, and did not return home until March 1877. Although she loved being in the house in Hastings and spent much time in the garden she had a wanderlust and in September 1878 this travel bug bit once again and she set off by ship to India, where she stayed for nearly six months,

By this time Marianne had built up a large collection of drawings which she had completed during her extensive travels. As they were so popular she held an exhibition of her work in a London gallery. Having been overwhelmed by their popularity she came up with the idea that they should be housed in a permanent collection and with this in mind she approached Sir Joseph Hooker, the director of the Kew Botanical Gardens in London and offered to present them with her art works and to fund the building of a gallery to house them. This was agreed and the architect James Fergusson submitted designs for the building and building work started in 1880. Sir Joseph Hooker as well as being a director of Kew Gardens was a good friend of Charles Darwin and he was introduced to Marianne and it was on his suggestion that she should visit Australia, and New Zealand to discover and sketch the native flora and vegetation. Marianne took up his suggestion and once again left her homeland and sailed to the antipodean.

On her return to England she set about arranging her paintings inside the newly completed gallery building at Kew and on July 9th 1882 it opened to the public as the Marianne North Gallery.

She resumed her travels visiting South Africa in 1883 and the following winter she was in the Seychelles. All this travelling and having to endure constantly changing climatic conditions eventually affected her health and, during her later years, she was unable to live a pain-free existence. She began to lose her hearing and in 1888 began to suffer from liver disease which finally claimed her life. Marianne North died on August 30th 1890 aged 60. Maybe it would be fitting to leave the last words to her sister Catherine who wrote about her sister:

“…The one strong and passionate feeling of her life had been her love for her father. When he was taken away she threw her whole heart into painting and this gradually led her into those long toilsome journeys. They no doubt shortened her life; but length of days had never been expected or desired by her, and I think she was glad, when her self-appointed task was done, to follow him whom she had faithfully loved…”

I have only been able to attach a few of Marianne’s numerous sketches and I am sure a visit to her gallery at Kew Gardens would be an amazing experience. For those of you who might not be able to make that journey may I suggest you get hold of her autobiography, the book which I have been reading and from which I gleaned most of the facts about this talented painter. It was not an expensive book and well worth the money. It is called A Vision of Eden; The Life and Work of Marianne North.