My Daily Art Display the other day featured one of the great American Realist artist Edward Hopper’s 1927 painting Automat and we looked at thetheme of loneliness and isolation in an urban environment. Today I am featuring a painting, which may

have influenced Hopper. It has had many titles but finally in 1893 the painting was simply called L’Absinthe. It was painted in 1876 by the French painter and sculptor and one of the founders of Impressionism, Edgar Degas.

Degas was born Hilaire-Germain-Edgar De Gas. Born in Paris in 1834, he was one of five

children of Augustine and Célestine De Gas. His father was a banker and Edgar was brought up in a moderately wealthy family environment. After the death of his mother when he was five years old, he was brought up jointly by his father and grandfather. He began school life at the age of eleven and at about this time dropped the use of the ostentatious spelling of the family name for the surname he is known by now, Degas. He finished his schooling at the age of nineteen and attained a baccalaureate in literature. When he left school he registered as a copyist in the Louvre. However his father had planned for his son to study law and enrolled him in the Faculty of Law at the

University of Paris. Edgar was very half-hearted about his father’s career choice and failed with his studies. He had been always interested in art and in his teenage years wanted to eventually become a famous history painter and paint pictures depicting great moments in history. This art genre had achieved immense popularity in France in the

nineteenth century. In 1855 he met the great French Neoclassical painter Ingres, who was his idol, and who offered Degas advice, which he was never to forget:

“..Draw lines, young man, and still more lines,

both from life and from memory, and you will become a good artist…”

He enrolled in the École des Beaux-Arts and a year later journeyed to Italy where he stayed for three years, part of this time was spent living with his aunt in Naples.

It was during this time that he studied the works of the great Italian Renaissance painters, such as Michelangelo, Raphael and Titian. He returned to France in 1859 and moved into

a Paris studio. His painting genre slowly changed from that of a history painter to one of a painter of contemporary subjects. He was still copying paintings at the Louvre and it was said that in 1864, whilst working on a copy of Velazquez’s portrait that he met another artist engaged in the same work. The artist was Édouard Manet, who was a key figure in the change-over from Realism to Impressionism and somebody who was to

influence Degas.

His painting career was temporarily halted for two years with the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. Degas enlisted in the National Guard and his military duties gave him little time for painting. With the conclusion of the war midway through 1871, his military life came to an end and the next year he went New Orleans where his brother, René, and other relatives lived. He returned to Paris the following year but sadly in 1874 his father died. A careful scrutiny of his father’s estate revealed that his brother René had amassed enormous business debts and Degas, wanting to preserve the good name of the family, had little choice but to sell his house and a large quantity of his art work to service the debt. Having always lived a relatively wealthy existence in which his art was mainly a hobby and for his own pleasure, Degas suddenly found himself having to paint pictures to sell and by so doing, put food on his table. Art historians believe it was during this time that Degas produced some of his greatest works.

It was also in this period of his life that Degas came together with a group of like-minded artists and together they put on independent exhibitions of their art works. The first of their exhibitions was held in 1874 and it was dubbed an Impressionist Exhibition. However, Degas did not like the label “Impressionists”, which the media had attached to his group of painters. Degas was a leading-light within this group and proved to be a great organiser.

His financial situation had improved by this time through the sale of his art and he developed a love for collecting works of art of the old Masters such as El Greco as well as works by his contemporaries, Manet, Pissarro and Cézanne. Alas, with age came his dissatisfaction with life in general. He became frustrated and disgruntled with life and became very argumentative and his friends began to desert him. Of Degas’ confrontational behaviour and loss of his friends, Renoir once commented:

“…What a creature he was, that Degas! All his friends had to leave him; I was one

of the last to go, but even I couldn’t stay till the end…”

Degas never married nor had any children. In many ways all he had was

his art and he lost that in the last few years of his life when his eyesight

started to fail. He died in Paris in 1917 aged 83.

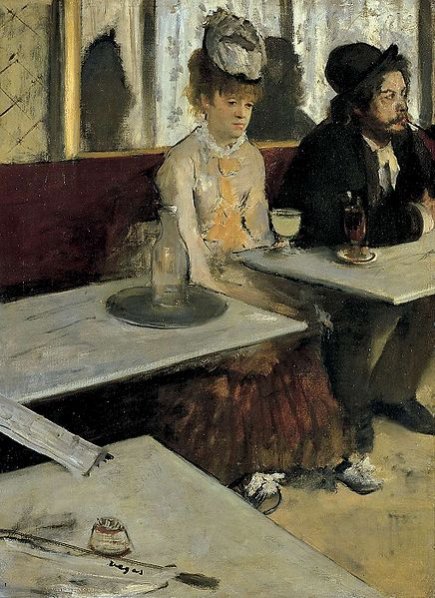

And so to the painting, L’Absinthe. We see two figures, one a man, the other a

woman sitting at a table outside a café. They are positioned to the right of centre of the painting which was a style often favoured by Degas. The man wearing a hat looks scruffy, almost tramp-like. His gaze is away from the woman and is fixed on something off the canvas, to the right of the picture. The woman is also wearing a hat and is dressed more formally than the man. She stares ahead with a blank expression, her arms hanging limply down by her side. On the table before her we see a glass filled with a green coloured liquid – absinthe. It is this drink which lends its name to the painting. This drink became very popular in France around 1850 and became commonly known as the queen of poisons or la fée verte (the green fairy). It is anise-based drink made from the wormwood herb and which is highly toxic and extremely addictive. It can have an alcohol content as much as 80 per cent by volume, twice that of spirits we buy today. It was a latter day drug. One critic condemned it saying:

“……Absinthe makes you crazy and criminal, provokes epilepsy and tuberculosis, and has killed thousands of French people. It makes a ferocious beast of man, a martyr of woman, and a degenerate of the infant, it disorganizes and ruins the family and menaces the future of the country….”

In some ways although this painting depicts two people sitting at the same table, the theme is loneliness and social isolation and the consequences. There is an air of desolation about the man and woman as they stare into space. Degas invites us to join these regulars at this café. Look how they sit side by side but there is no contact between them. There is no animated conversation between them. Degas is showing us that you can be together but still be alone. Maybe they can gain some comfort from their individual loneliness.

She sits with her absinthe before her. He is with his black coffee, probably trying to counteract the effects of too much absinthe. In my mind, there is a feeling of isolation

permeating from this work. In this case the isolation may be due to the fact that this pair are heavy drinkers and for that reason they are shunned by society. Although this is a café scene, the painting could be classed as a portrait as both the man and the woman were known to the artist. The woman, dressed up as a prostitute, was the famous French actress Ellen Andrée, who modelled for many of the Impressionist artists and the man was Marcellin Desboutin, a painter and engraver who favoured the Bohemian lifestyle. Degas wanted his two models to pose as absinthe addicts in front of his favourite café, the Café de la Nouvelle-Athènes, which was situated in the Place Pigalle in Paris. It was a popular meeting place for Degas and Impressionist painter friends such as Manet, and van Gogh and this quaint meeting place existed up until 2004.

The painting which now hangs in the Musée d’Orsay was first exhibited in 1876 but was not well received by the critics. For them it was “ugly and disgusting”. In 1892 when it came up for auction at Christie’s the lot was greeted with “boos and hisses” ! For

many critics the painting was looked upon as a blow to morality. The English viewed French art with grave suspicion as to its morality and preferred paintings which were morally uplifting and incorporated a moral lesson. George Moore the Irish writer and art critic of the time described the woman in the painting:

“…What a whore…”

and of the painting itself critically uttered:

“….the tale is not a pleasant one, but it is a lesson….”

Amusingly once the painting had been exhibited Ellen Andrée became a larger than life figure and a succès de scandale, which only goes to confirm that there is no such thing as bad publicity. The French government, at the time, took a much dimmer view of the painting and the furore that had risen from it. They tried to dampen down to the controversy by saying the green drink on the café table was simply green tea!!!