Marie Laurencin – a photograph by Granger (1913)

Marie Laurencin left Spain and returned to Düsseldorf via Switzerland in 1919. She was very unhappy with her life. She was depressed and felt unstable with her marriage failing. Laurençin filed for a divorce from her husband telling friends that the reason for the marital split was because her husband had become an alcoholic. In 1921 Laurençin returned to Paris, knowing that her marriage was finished and she divorced von Wätjen. However, despite the divorce, they remained on good terms, and Marie kept in touch with van Wätjen’s until his death in 1942.

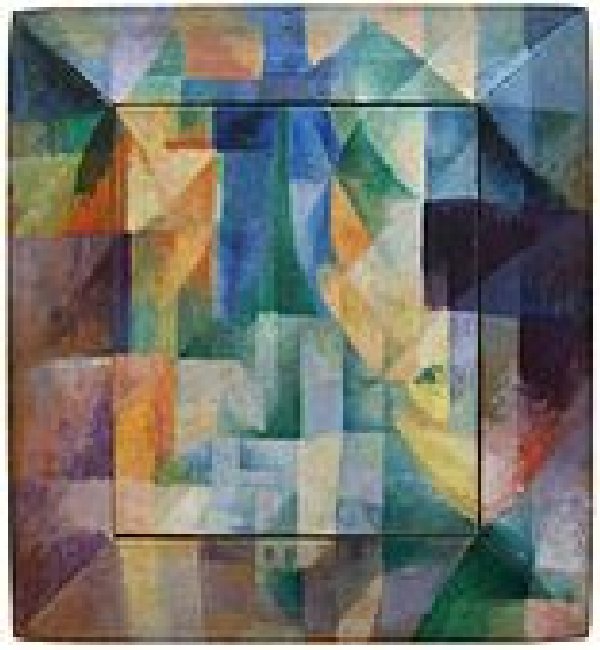

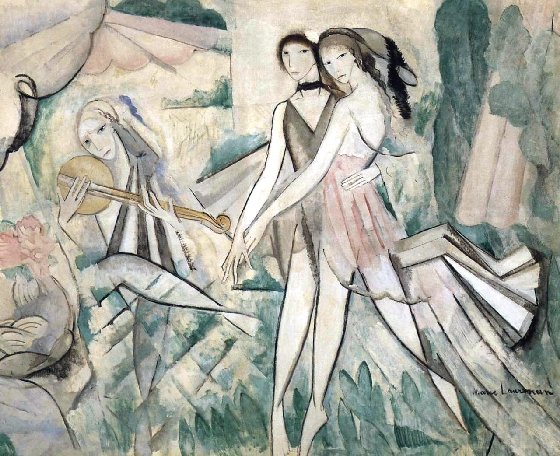

The Spanish Dancers by Marie Laurencin (1921)

Now having returned to the French capital Marie realised that she had been greatly affected by her separation from Paris which she looked upon as the unrivalled centre of artistic creativity. After her return, she developed a new style of painting which is reflected in her 1921 work, The Spanish Dancers. Gone are the muted colours and the geometric patterns she had inherited from Cubism and these are replaced by light tones and undulating compositions. Once again, we note the coming together of the feminine world and the animal world, which became her favourite theme. In the work we see three young women spinning around a small bounding dog, in front of a large grey horse. Marie has portrayed herself kneeling in the foreground wearing a pink tutu, which happens to be the only warm tone in the painting. Her hands are entwined with those of the young woman on the right, who is wearing a light grey dress with a light blue headscarf. The woman on the left, wearing a light blue dress, is executing a dance step whilst holding a hat in place on her head. Her eyes lead almost seamlessly into the large almond-shaped eye of the horse. The animals would appear to be the dancers’ confidantes in this strange setting.

Femme aux tulipes by Marie Laurencin (1936)

Now back in Paris, Paul Rosenberg began to act as Marie Laurencin’s dealer which afforded her enhanced financial security and he also provided her with sound business advice. Unfortunately, she did not always take Rosenberg’s advice and he was horrified to find that Marie often gave her work as a gift to those she liked. She also set higher prices for work which she found dull and often discounted some of her favourite works. Curiously she often charged men double what she asked of women, and even charged brunettes more than blondes and furthermore she had a reputation for painting only children whom she liked.

Jeunesse by Marie Laurencin (c.1946)

In her private life, while Marie Laurençin had a succession of male lovers, she also had close female friendships and lesbian relationships. She became part of the female expatriate community in Paris that searched for both artistic and sexual liberation. Lesbianism, for many of these women, was a crucial element of their resistance to bourgeois social conventions.

Gertrude Stein at 27 rue de Fleurus with her portrait by Picasso on the wall, May 1930

Now, based in the French capital, Marie was alone. The first American who befriended her and bought her paintings was Gertrude Stein, an American novelist, poet, playwright, and art collector who had been born in Pennsylvania. She had moved to Paris in 1903 and made France her home for the remainder of her life. She hosted a Paris salon, where the leading figures of modernism in literature and art, such as Pablo Picasso, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Sinclair Lewis, Ezra Pound, Sherwood Anderson and Henri Matisse, would meet for conversation and inspiration. Laurençin soon became part of the Stein salon on rue de Fleurus. Marie remained in contact with Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas until Stein’s death in 1946 and continued to see Toklas until her own death.

Portrait of Coco Chanel by Marie Laurencin (1923)

Laurencin held an exhibition of her work in 1921 at the Rosenberg Gallery in Paris. She had now built up her reputation as a talented portraitist, especially of celebrities, one of whom was Coco Chanel. The commission to paint Chanel’s portrait came about in the autumn of 1923 when Marie Laurencin was working for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes which was established in Paris, Monte-Carlo and London, and Marie was designing the costumes and sets for the ballet Les Biches [The Does]. At the same time, Coco Chanel was creating the costumes for the same company’s Le Train Bleu [The Blue Train] operetta . At that time, Coco Chanel was both very rich and famous, and she commissioned Marie Laurencin to paint her portrait. This was one of Laurencin’s early portrait commissions. Laurencin depicted Chanel face-on, seated in a relaxed, somewhat dreamy pose, with her head resting on her right arm. She appears relaxed and her eyes and mouth, neutral and expressionless, suggest that she is daydreaming or preoccupied by her thoughts. Marie Laurencin’s painting style was to incorporate animals in her works and here she depicts a white poodle sitting on the Coco Chanel’s knees. It is unclear where Chanel’s flesh ends and her dress begins; her pale outfit is accented with dark black and blue scarves, while the seat behind her is a textured pink and blue. On the right-hand side of the painting, we can see another dog leaping upwards towards a turtle dove which appears to be descending from the sky towards Coco Chanel, like the dove of the Holy Spirit, and thus Laurencin’s symbolising it as a sort of freedom. The colour palette is of a soft harmony of the colours – green, blue and pink, which is reinforced by the long black line of the scarf draped around the model’s neck. The finished painting was so like Laurencin’s earlier works but did it capture the likeness of Coco Chanel. The sitter did not think so and the artist did not deny it, but claimed that physical likeness was unimportant. Chanel refused to pay for it and Laurencin was so annoyed by Chanel’s attitude that she refused to execute a second portrait and decided to keep the original herself. Despite Chanel’s rejection of the painting, the success of Laurencin’s approach to portraiture was such that she continued to receive and execute portrait commissions in this style until the 1940s. The painting can now be found at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris.

In 1931, Laurencin was one of the founding members of La Société des femmes artistes modernes, and took part in their annual exhibitions until the outbreak of World War II. During the period from 1932 to 1935, she tutored at the Villa Malakoff, a private art school. In 1937, which art historians believe was the height of her career, a retrospective of Laurencin’s work was held in conjunction with the Great Exhibition of Independent Art Masters at the Petit Palais, which sought to promote the superiority of the contemporary French artistic school, extended to foreign artists “living or having lived in France for many years”. The year 1937 saw a change in Laurencin’s appearance when she finally acquired glasses, which changed her life considerably as she had been extremely short-sighted since childhood and had had difficulty negotiating staircases since the 1920s.

During World War II, Laurencin remained in Paris painting and working on designs for the ballet, and in 1942 she published Le Carnet des Nuits – a collection of poetry with short memoir pieces in prose. Although Laurencin will be remembered as an artist and the grace and the elegance of her artworks; she is also the author of a diary, Le Carnet des Nuits, an important witness of her time. It tells of her early years she spent in Bateau-Lavoir. Her writing is of the same delicate style used for her artworks.

Head of a Woman by Marie Laurencin (1909)

In later years, Laurencin became withdrawn and increasingly isolated and sadly suffered from periods of depression and other health complaints, albeit, she continued to paint throughout this troubling passage of time. Her main companion was her maid, Suzanne Moreau, who had lived with her since 1925. Whether there was more to the mistress/servant relationship is unclear but it is thought that they were romantically linked. In 1954, Laurencin made Moreau the beneficiary of her estate. It is thought this came about due to Laurencin’s legal struggle, resolved the following year, with tenants living in the apartment that she owned.

The tomb of Marie Laurencin in Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris.

Laurencin died of a heart attack on June 8th, 1956, aged 72. She was buried wearing a white dress in Père-Lachaise cemetery in Paris, as per her wishes, with Apollinaire’s love letters and a rose in her hand.

The main source of information for the three blogs about Marie Laurencin came from the excellent The Art Story website.