Houses at Semur by Laura Wheeler Waring (1925)

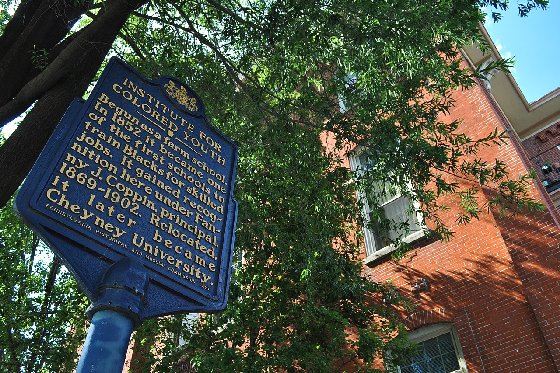

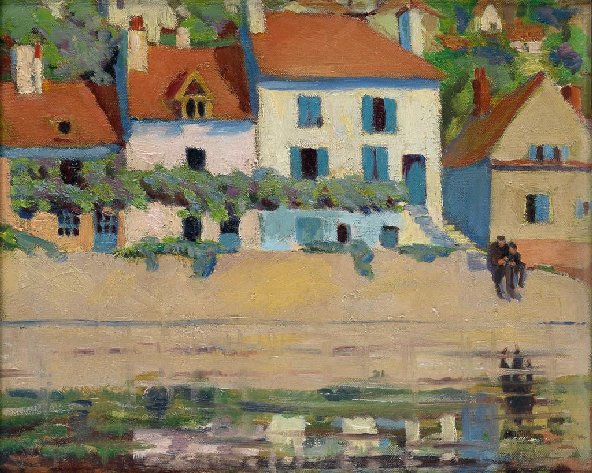

Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port by Laura Wheeler Waring (1925)

After her short stay in the south of France, Waring returned to Paris in the Spring of 1925 and continued her studies at the Académie de la Grande Chaumiére whilst staying in the Villa de Villiers in Neuilly-sur-Seine. That year Laura completed her paintings, Houses at Semur, France and Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port. Critics believed this was a turning point in her artistic style as we see her use of vivid colours in order to express vivid, brilliant atmospheric conditions. Both works enhanced her growing reputation. The following year, she had works shown at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C., the Brooklyn Museum, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. And her standing in the art world was such that she was asked to curate the Negro Art section at the Sesquicentennial Exposition in Philadelphia.

On June 23rd, 1927, Laura Wheeler was married to the Philadelphian, Walter Waring, a public-school teacher, who was ten years her junior and who was then working as a professor at the all-Black Lincoln University. The couple had no children. That same year, Laura won a gold medal in the annual Harmon Foundation Salon in New York. Laura Waring was actively painting during the Harlem Renaissance. The Harlem Renaissance was an influential movement in African American literary, artistic, and cultural history from 1918 to the mid-to-late 1930s. The movement was originally referred to as the New Negro Movement, which referred to Alain LeRoy Locke’s 1925 book, The New Negro, which was an anthology that sought to motivate an African-American culture based in pride and self-dependence.

She was also involved with the Harmon Foundation. It was established in 1921 by wealthy real-estate developer and philanthropist William E. Harmon who was a native of the Midwest, and whose father was an officer in the 10th Cavalry Regiment. The Foundation originally supported a number of good causes but is best known for having served as a large-scale patron of African-American art and by so doing, helped gain recognition for African-American artists who otherwise would have remained largely unknown.

In 1944 the Harmon Foundation, which was under the direction of Mary Beattie Brady, organized an exhibition Portraits of Outstanding Americans of Negro Origin. The idea behind the exhibition was to try and counteract racial intolerance, ignorance and bigotry by illustrating the accomplishments of contemporary African Americans. The exhibition featured forty-two oil paintings of leaders in the fields of civil rights, law, education, medicine, the arts, and the military. Betsy Graves Reyneau, Laura Wheeler Waring, and Robert Savon Pious painted the portraits that became known as the Harmon Collection. US Vice President Henry A. Wallace presented the first portrait, which featured scientist George Washington Carver, to the Smithsonian in 1944. The Harmon Foundation donated most of this collection to the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in 1967.

Anna Washington Derry by Laura Wheeler Waring (1927)

Laura Wheeler Waring will always be remembered for her portraiture and her most acclaimed work was not of the prosperous and famous African Americans which I have highlighted below but of a poor laundress, Anna Washington Derry. She was one of five children who had moved with her family from Maryland to the eastern Pennsylvanian town of Strodsburgh, a borough in Monroe County. Monroe was home to a small free Black community who had arrived via the Underground Railroad, a network of secret routes and safe houses used by enslaved African Americans to escape into free states.

The beautiful realistic depiction of the old lady beautifully conveys the lady’s dignity and inner determination through her use of simple, brown-beige tones of her dress, her expressive face, her folded arms and hands. In the town where she lived Derry was looked upon as that of a community matriarch who was fondly addressed locally as “Annie”. The portrait was unveiled in 1926 at an elite exhibition for Black Philadelphian professionals some of whom may not have identified with Waring’s “ordinary” subject. The art historian Amanda Lampel commented:

“…Although Derry’s portrait did not sell that day, the Philadelphia Tribune, the oldest continuously published African American newspaper in the United States, called it remarkable……… Compared to fellow contemporaries like Aaron Douglas, Waring was much more conservative in her painting style and subject matter. This was in keeping with the types of artists who won the prestigious Harmon Foundation award, which sought to spotlight the up-and-coming Black artists of the Harlem Renaissance. Most of the award winners painted more like Waring and less like Douglas…”

In 1927 Laura exhibited the portrait of Anna Washington Derry at New York’s Harmon Foundation where it received the First Award in Fine Art – Harmon Awards for Distinguished Achievement Among Negroes. From there it was exhibited at Les Galeries du Luxembourg in Paris and across America. The depiction was often reproduced in magazines and journals. The exhibition had its premiere at the Smithsonian Institution on May 2nd, 1944. For the next ten years, Portraits of Outstanding Americans of Negro Origin, exhibition, travelled to museums, historical societies, municipal auditoriums, and community centres around the United States. The public response was overwhelmingly positive in every venue.

James Weldon Johnson by Laura Wheeler Waring

Laura Wheeler Waring will be most remembered for her portraits of successful, upper class Negroes and whites including James Weldon Johnson, the successful Broadway lyricist, poet, novelist, diplomat, and a key figure in the NAACP, National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People. In 1900, he collaborated with his brother to produce “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” a song that later acquired the subtitle of “The Negro National Anthem.”

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois by Laura Wheeler Waring

Another sitter for Laura was William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (W.E.B. DuBois), who was the first African-American to earn a doctorate from Harvard University He then became a professor of history, sociology, and economics at Atlanta University, and co-founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP), and founder and editor of the NAACP’s magazine The Crisis. Laura Waring had worked for Du Bois, creating several illustrations for The Crisis. Laura depicts Du Bois seated at a wooden desk or table, looking to the right. The spectacles he holds in his right hand, and the small paper he holds in his left, confirm his status as an intellectual and academic.

Marian Anderson by Laura Wheeler Waing (1947)

Many women were sitters for Laura’s portraits including Mary White Ovington, an American suffragist, journalist, and co-founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP). Another of her most famous female portraits was of the opera singer, Marian Anderson. This contralto singer, like many African American artists of the time, first achieved success in Europe. She was persuaded to return to America in 1935 and that year had a triumphant concert which secured her standing in the opera world. In 1939 she became embroiled in a historic event when the Daughters of the American Revolution banned her appearance at its Constitution Hall because she was black. President Roosevelt’s wife, Eleanor, stepped into this controversial banning and arranged for her to take top billing at the Easter Sunday outdoor concert at the Lincoln Memorial, an event which drew in 75,000 opera fans as well as having the event broadcast to a radio audience of millions.

Jessie Redmon Fauset by Laura Wheeler Waring (1945)

Another female to have her portrait painted by Laura Wheeler Waring was Jessie Redmon Fauset, the first African American woman to be accepted into the chapter of Phi Beta Kappa at Cornell University, where she graduated with honours in 1905. Fauset then taught high school at M Street High School (now Dunbar High School) in Washington, D.C., until 1919 She then moved to New York City to serve as the literary editor of the NAACP’s official magazine, The Crisis. In that role, she worked alongside W. E. B. Du Bois to help usher in the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s.

Alice Dunbar-Nelson by Laura Wheeler Waring (1927)

In the 1890s women formed national women’s club federations, most of which were dominated by upper-middle-class, educated, northern women. Few of these organizations were bi-racial, a legacy of the sometimes uneasy mid-nineteenth-century relationship between socially active African Americans and white women. Rising American prejudice led many white female activists to ban inclusion of their African American sisters. The black women’s club movement rose in answer in the late nineteenth century. The segregation of black women into distinct clubs produced vibrant organizations that promised racial uplift and civil rights for all blacks, as well as equal rights for women. Soon there followed another, more powerful group known as the National Association of Coloured Women in 1896. Women, including Laura Wheeler Waring and Alice Dunbar-Nelson, came together from a variety of backgrounds to combat negative stereotypes and fight for basic rights. Alice Dunbar-Nelson became the subject of Laura Wheeler Waring’s 1927 portrait. By the time the portrait was completed, Dunbar-Nelson was a prominent political activist and journalist and was much in demand as a public speaker. The depiction of her radiates her self-confidence and both artist and sitter were talented, intellectual women whose friendship helped advance the rights of both women and African Americans.

Waring died on February 3rd, 1948, aged 60, in her Philadelphia home after a long illness. She was buried at Eden Cemetery in Collingdale, Pennsylvania. In 1949, Howard University Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. held an exhibition of art in her honour. Her paintings were also included in the 2015 exhibition We Speak: Black Artists in Philadelphia, 1920s-1970s at Philadelphia’s Woodmere Art Museum.

Laura Wheeler Waring (1887-1948)

There is no doubt that although Laura spent most of her life in America she always treasured her three stays in France which played an important role in her artistic progress. During those three periods on French soil she was able to engage in its culture, and associated with famous French, African, and African American intellectuals. Her scholarship, her study at the Academie de la Grande Chaumiere, and her solo exhibition in Paris gave her recognition in the United States in the form of awards, supervisory and teaching positions, and additional exhibitions. Like many of her colleagues, Waring cherished the freedom she found abroad, declaring in her diary:

“…In my very busy seasons here to come I shall want to relive some of these moments of atmosphere. I record them so that I can never say “I wish I had enjoyed that more” or “I didn’t apprecate all that then but now—[.]” I can never say the above truthfully because am grateful every minute and even the least of things gives me a thrill. . . . The very feeling of freedom is a pleasure and the ride on the bus down will be a joy…”

Much of the information for this blog and many of my other blogs in the past has come from an excellent website entitled The Art Story.

Other sources were:

A CONSTANT STIMULUS AND INSPIRATION”: LAURA WHEELER WARING IN PARIS IN THE 1910s and 1920s by Theresa Lieninger-Miller