Four years ago I visited the Courtauld Gallery in London to see the Cezanne exhibition which featured three of his five Card Players paintings. I was fascinated by the figures depicted in these works of art, the same fascination the artist must have had for these rustic characters as they featured in many of his paintings. From around 1887, Cézanne began to paint single figures again and, in his early works, he would used his wife and son as models, later he would get some of the peasant workers to model for him at the family’s estate, Le Jas de Bouffan, (“home of the winds” in the language of Provencal). In this blog I want to have a look at some of his paintings which featured these peasants and the estate where it all happened.

Paul Cézanne’s father, Louis-Auguste Cézanne, was a banker and in September 1859, when Cézanne was twenty years old, his father acquired the Le Jas de Bouffan estate from its then present owner, Gabriel Joursin, who was heavily in debt to the bank. It was a spectacularly beautiful estate, located on the outskirts of Aix-en-Provence, with its long avenue, lined with chestnut trees, leading to the large manor house. The family moved into the large estate house, which was run-down, some of the rooms were in such poor condition that they could not be lived in and were permanently locked up. Initially the family just lived on the first floor with the ground floor rooms set aside for storage. Cézanne, who much to his father’s dismay, wanted to become a professional artist but had placated his father by agreeing to study law at the Law faculty at Aix. His father allowed him to paint murals on the high walls of the grand salon on the ground floor, a room which he was eventually allowed to turn it into his temporary studio.

It could have been that as the surface of the walls was in such a poor condition his father allowed his son to exercise his artistic ability on them. Cézanne decorated the walls with four large panels of the Seasons. The odd thing about his four murals was that he signed them, not with his own name, but with the name “INGRES” and added the date 1811 on the bottom left of the panel representing Winter. So, why sign the painting “Ingres” and why the date, which was almost fifty years in the past? It is thought that the young Cézanne wanted to prove to his father that he was as good an artist as the legendary Ingres and the date probably referred to Ingres’ famous work Jupiter and Thétis, which Ingres completed in 1811 and was in the collection of Cézanne’s local museum, Musée Granet, in Aix-en Provence.

In all, between 1860 and 1870, Cézanne painted twelve large works of art directly on to the walls of the large salon and which remained in situ until 1912. One of these works was entitled The Artist’s Father, Reading “L’Événement” which can be seen at the National Gallery of Art, Washington. Cézanne completed the work in 1866 and depicts Louis-Auguste Cézanne reading the newspaper L’Evénement. The newspaper is a reference to Cézanne’s great friend from his childhood days, the novelist Émile Zola, who was one of the people who urged Cézanne to overcome his father’s demands to have him study law and instead, go to Paris and study art. Zola had become the art critic for the L’Evénement in 1866. It was certainly not the paper Cézanne’s father would have read !

Although often working in his indoor studio, Cézanne also enjoyed painting en plein air in the vast grounds of the estate, which contained a farm, as well as a number of vineyards. He painted a number of views of the manor house, one of which was completed around 1874 and was entitled The House of the Jas de Bouffan. In this work we see the great old ochre-coloured building, with its ivy- clad walls nestled amongst a thriving mix of tall, well-established trees and greenery. It is a beautiful sunlit scene which captures the myriad of visual wonders offered up by nature. Cézanne despite moving around the country, including Paris, where he exhibited works at the first Impressionism exhibition in April 1874, often returned to Jas de Bouffan to relax and paint. The roof of the house had to be replaced in the early 1880’s and it was then that Cézanne’s father made a little studio in the attic for his son. In 1886 when his father died, Cézanne came into a large inheritance which included the family’s beloved estate. This was the same year he married his lover and artist’s model of seventeen years, Hortense. In September 1899, two years after the death of his mother, Cézanne and his two sisters sold Jas de Bouffan to Louis Granel, an agricultural engineer.

Much later, the house and a portion of the grounds were sold to the city of Aix. The house has been open to the public since 2006 for visits in connection with the tours organized by the Office de Tourisme with regards to the life of Cézanne.

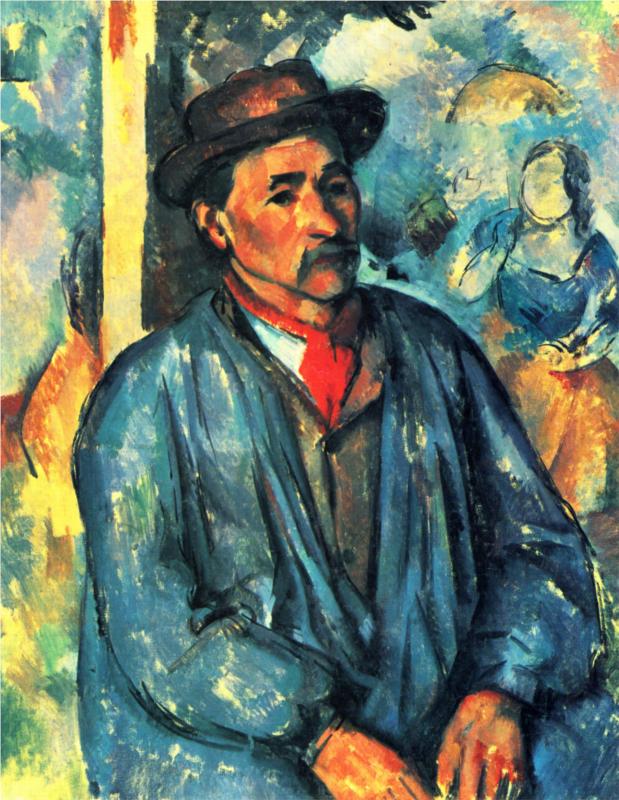

As I wrote before, in the late 1880’s Cézanne began to concentrate once again on single portraits and used his wife Hortense and son Paul as models. Later, in the 1890’s he started to paint a number of pictures which featured some of the workers of the estate. Using actual peasant workers that he knew added that little bit extra realism to the depictions. One such work was entitled Man in a Blue Smock which he completed around 1897 which is now housed in the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth. The worker who sat for Cézanne in this painting was also one of the models used for the famous Card Players series. It is an interesting work which needs to be carefully studied. The man, with a large moustache, shows little expression as he sits before Cézanne, the artist and his boss! It appears that he has been asked to put on a painter’s blue smock over his ordinary working clothes, which includes a red bandanna

The painting of the peasant is awash with muted blues and browns but the red used for the bandanna, the man’s cheeks and the backs of the hands draw our eyes to these very points in the painting. The background of the work is predominately filled with pastel colours but what is most interesting is what is behind the left shoulder of the main character. One can make out a faceless lady carrying a parasol. The museum curator believes that this faceless woman perhaps suggests some mute dialogue between opposite sexes, differing social classes, or even between the artist’s earliest and most fully evolved efforts as a painter. This latter reason falls in well with the fact that the lady with the parasol is a copy of one of Cézanne’s first works which he completed in 1859, when he was twenty years of age, and which can now be found in the Musée Granet in Aix.

Another painting featuring one of his peasant workers is entitled Seated Peasant which he completed around 1896 and is part of the Annenberg Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York The peasant in the painting is young and is seated cross-legged on a cane chair. The setting for the painting is inside one of the rooms in the big house. It is “L-shaped” in design. The background is once again a simple plastered wall with its dado rail. Cézanne has restricted his palette to a small number of colours – greys, blues, browns, yellows and grey greens which are only replaced by the odd small splash of purple and red. Although there is a similarity between him and the peasants in the various Card Players works he has never been identified as being in any of those five famous paintings. The man seems lost in thought. His mouth is drawn down on each side giving his facial expression an air of melancholia. He wears a baggy dark brown coat over a grey jacket and a yellow waistcoat or vest. He wears striped trousers. Look at the way Cézanne has painted his hand which rest on his thigh. It is very large in comparison to the rest of his body and could almost be described it as being “ham-fisted”. As in some other portraits by Cézanne, he has introduced a still-life element into the work. On the floor in the bottom left of the painting he has added two green-bound books, two small boxes, a small bottle and a stick all of which have been placed on a cloth. Only the artist knows why he included these inanimate objects into this portrait! Maybe he was asserting his ability to paint still-life objects.

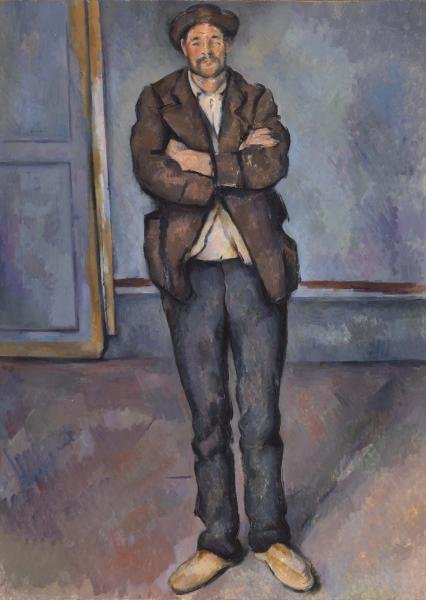

Around the same time, Cézanne painted another portrait of a peasant in a standing position. It looks very much like the setting for the portrait was in the same room as the previous work. It was entitled Paysan debout, les bras croisés, (Peasant Standing with Arms Crossed) and was completed around 1896.

My final work I am showcasing is a head and shoulder depiction simply entitled Le paysan (Peasant) which Cézanne completed around 1891. Again we have this peasant with a most unhappy countenance as he stares downwards. Again his mouth is turned down in an expression of sadness. One has to believe that this is the pose Cézanne wanted his sitter to exhibit. Was the artist trying, by this posed facial expression of his sitter, to get over to us that the life of a peasant was not a happy one. Maybe Cézanne want us to empathize with the man. Maybe Cézanne was determined to depict the inequalities of life in this portrait. Once again the background is plain and in no way detracts from the sitter. The work is a mass of greys and blues but the careful splashes of red on the peasant’s face make us focus on the man’s expression and by doing so poses the question to us as to what we think about is his lot in life.