Arnold and Louise settled down to living in the Colorado town of Denver in 1926. Soon the couple became active in the Denver art community and both were founding members of the Denver Artists Guild in 1928. Whilst living in Denver during the 1920s and 1930s, they would regularly visit Santa Fe in New Mexico and when in Taos would be guests at Mabel Luhan’s Los Gallos compound.

The Rönnerbeck Family (1937)

The help Louise received from the WPA was just what she needed as her portrait commissions had dwindled due to the Depression and the little savings she had left from a family inheritance was quickly diminishing. Besides her portraiture she had always been interested in painting murals and accordingly she worked long and hard and entered a number of WPA competitions to win mural commissions in various US States. In all, she entered sixteen mural commission competitions for the Treasury Department Section of Painting and Sculpture, a New Deal art project established on October 16, 1934, and administered by the Procurement Division of the United States Department of the Treasury.

The Fertile Land Remembers, oil on canvas mural by Louise Rönnebeck for the Worland, Wyoming Post Office, now in the Dick Cheney Federal Building, Casper, Wyoming, (1938)

In many of her submissions she focused on the power of women in striving for their goals but also depicted the plight of women and the children who were forced to work at a young age. In the end, she was awarded two commissions. In November 1937 she was invited to submit sketches for a mural that would decorate a wall in the post office of the Wyoming town of Worland. The Worland commission was for $570 and the artist was allowed 119 days for its completion. The organisers wrote Ronnebeck that the mural called for a “simple and vital design” based on a theme appropriate to the locale. Awarding Louise the Wyoming commission was a controversial decision as she was living in Colorado and many believed the commission should have gone to a Wyoming-based artist but the organisers stated bluntly that no Wyoming artist reached the standards they required. Louise commenced her oil on canvas mural entitled The Fertile Land Remembers in 1938. The mural depicts a white American couple with their child sitting in a wagon being pulled by two large oxen. These three figures, all looking towards us, are painted in a variety of rich colours whilst the native Indian horseback riders seen chasing buffalo are portrayed cloud-like figures in the sky above the wagon and are depicted in pale monochromatic luminous grey. None cast their eyes towards us. They are probably Cheyenne or Sioux, the forgotten people of Wyoming, who lived a nomadic lifestyle in order to pursue buffalo herds and were subdued and placed in reservations. Unlike the colourful people in the wagon being the present and future the pale grey figures are symbolic of the past. In the background we see the emerging elements of the white American future. Louise wrote about her thought process that went into the mural design:

“…The work is a romantic recollection of the covered wagon and the wild Indian and bison of the Old West, who still in retrospect hover over the irrigated fields and oil wells of the present. The covered wagon drawn by oxen is shown inexorably pressing through the galloping figures of a vanishing culture, whose form becomes shadowy and disappear into the past under the white man’s determination to open new lands. The landscapes on either side depict the present which was created by these pioneers. The way in which the idea is presented was suggested by the device of the double exposure used in many motion pictures to show the past and the present merging into one dramatic unit…”

Harvest by Louise Rönnebeck (1940)

Louise Rönnebeck’s second commission was for the post office and courthouse in the Colorado town of Grand Junction but which is now housed in the city’s Wayne N. Aspinwall Federal Building United States Courthouse. Louise won the opportunity to paint The Harvest through entering a contest anonymously, for fear of gender prejudice, and submitting a sample sketch. In 1940, with the enlargement of the Wayne N. Aspinall Federal Building, Rönnebeck’s mural was placed to embellish the postmaster’s office door pediment with its conspicuous V-shaped bottom. Her depiction represented the plight of the Native American Ute people who prior to the 1860s had lived in southwest Colorado for centuries and it was here that they had their seasonal hunting grounds. However, despite a Treaty which granted the Utes absolute and undisturbed use and occupation of their land, the lure of rich mineral deposits lured prospectors on to their land. The tribe was squeezed into an ever-smaller parcel of land by the incoming miners. The matter came to a head in 1881 when the Utes refused to leave the territory and were forced to the south-western border of Colorado. The six million acres of land once owned by the Utes was now up for grabs and settlers poured in establishing local industries such as orcharding in the form of growing peaches. In the foreground of Louise Rönnebeck’s large mural we see the harvesting of the peach crop by a young couple, modelled by Louise’s two children. To the left of the painting, we see settlers moving into the Ute’s land with their horses and to the right we see the result of this influx as the Ute people are forced out. This is a painting depicting a thriving local industry and acts as a counterpoint to the hard times of the Great Depression.

Unveiling of “missing” painting.

In a January 18th, 1992, article by Ginger Rice in Grand Junction’s Daily Sentinel, it describes the mural’s mysterious disappearance for more than twenty-five years. Workers removed the oil-on-canvas painting for conservation work, and it subsequently went missing. Fortunately, a General Services Administration building manager, Tim Gasparani, re-discovered the mural and in 1992, The Harvest finally returned to its original home.

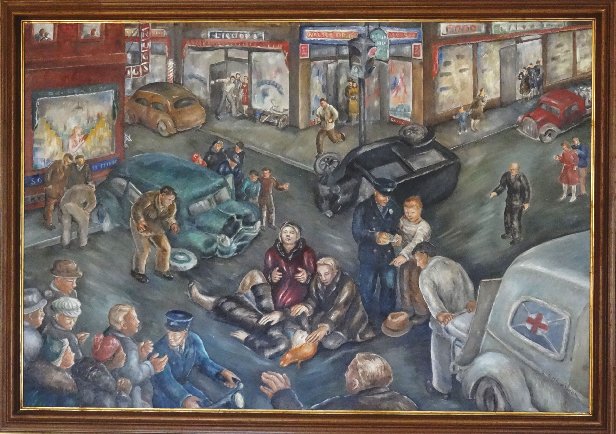

The People vs Mary Elizabeth Smith. by Louise Emerson Rönnerbeck (1936)

In 1936, Louise Rönnerbeck completed a dramatic painting entitled The People vs Mary Elizabeth Smith. The depiction was based upon an emotional trial of an eighteen-year-old mother of a eight-month old child, Mary Elizabeth Smith, in January 1936. She, whom the press termed “the girl mother” had been accused of murdering her husband in the previous November. She had accused her estranged husband, nineteen-year-old Robert Dwight Smith, who was unemployed, as being abusive towards her. Just prior to the shooting he had petitioned the court to annul their three-year-old marriage which would result in their child being looked upon as being illegitimate. For Mary Elizabeth, this was too much to bear and so she took her brother’s hunting rifle, marched along to her sister-in-law’s house where her husband was staying and shot him. She told the police that she did not know why she did it. She just knew she had to protect her baby’s name. Her defence lawyers stated that having been deserted by her husband and struggling to bring up their son it had taken its toll on her mental health. Louise Rönnerbeck depicted the theatrical trial scene which she had witnessed.

The defence lawyer mitigated the actions of his client by reminding the jury of her personal history. Her father had deserted her leaving her mother to struggle to provide for her two children. Her own eight-month-old son, Rodney, born after a particular long and painful labour was the centre of her life. The courtroom was filled throughout the trial and the press feasted on the events. In his article, Jack Carberry of the Denver Post wrote:

“…”they met love, and in their ignorance of life, it engulfed them…”

Rönnebeck’s painting depicts the dramatic trial scene. In the witness box, at the centre of the legal proceedings, we see the frail reed-headed defendant, wearing a dark dress with a white collar, handkerchief in hand, as she grasps the side of the witness box. She is barely able to stand and is fully aware that if the all-male jury (at this time women were not allowed to be jury members) convicts her, she faces either the death penalty or life imprisonment. It was reported in the Denver Post that her testimony was one of child-like simplicity. On the left in the front row of the courtroom we see the girl’s mother holding her daughter’s infant son. She had come every day to offer support to her daughter. After Mary’s testimony it was reported that there was not one person in the courtroom who wasn’t crying, moved by the young woman’s simplistic testimony. Also in the scene we see the prosecutor waving the murder weapon and on a table to his right are the deceased bloodied shirt and trousers. The jury retired for five hours before returning and acquitting her for reasons of insanity.

The Children by Louise Emerson Rönnebeck (c.1935)

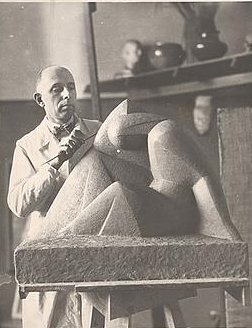

Following the end of World War II, Louise lectured at the University of Denver from 1945 to 1951 as well as providing some magazine illustrations. Her husband Arnold died of cancer on November 14th 1947, aged 62 and with her two children marrying, Arnold in 1950 and Ursula in 1953, she was left on her own. In 1954 she went to live in Bermuda where she and her family had spent many holidays. Here she taught art at the Bermuda High School for Girls between 1955 and 1959 and continued to paint. In the Autumn of 1973 she returned to Denver where she spent the rest of her life.

Louise Emerson Rönnebeck died in Denver on February 17th 1980, aged 78.

I collected information regarding the life and art of Louise Emerson Rönnerbeck from various sources. The main ones were: