My Daily Art Display today looks at a work by the French painter Jean-Baptiste Greuze. His work was praised by the French philosopher and writer Denis Diderot who claimed that Greuze’s paintings were, as he succinctly put it, “morality in paint” and as such represented the highest ideal of painting in his day. So who was this moralistic painter?

Jean-Baptiste Greuze was born in Tournus, a Burgundian town on the banks of the River Saône in 1725. He came from prosperous middle-class family and studied painting in Lyon in the late 1740’s under the successful portrait painter, Charles Grandon. Around 1750 Greuze moved to Paris where he entered the Royal Academy as a student. It was whilst there that he developed a style of painting which was described as Sentimental art, but more about that later. He was accepted as an Associate member of the Academy after he submitted three of his paintings A Father Reading the Bible to His Family, The Blindman Deceived and The Sleeping Schoolboy. These moralising pictorial stories, which in some ways remind me of the works by William Hogarth some two decades earlier, were about life amongst working class folk. It was this genre of art which depicted scenes from the lives of ordinary citizens and which were calculated to teach a moral lesson – that would be Greuze’s trademark for the rest of his life.

Although Greuze was happy to be admitted to the Academy on the strength of his three genre paintings he strived to be accepted as a history painter which, in thiose days, was considered a higher rank of art. However the Academy did not look favourably on his attempts at history paintings and this rebuff so annoyed Greuze that he refused to submit any more of his works for the Academy’s exhibitions. Fortunately for Greuze the public liked his “sentimental” paintings and the sale of his works continued strongly, which meant he had no more need to exhibit his works at the Academy.

During the late eighteenth century in France, Rococo art had almost taken over the French art scene. It was all the rage with its mythological and allegorical themes in pastoral settings and its elegant and sometimes sensuous depictions of aristocratic frivolity. At this time this brand of light-hearted, and now and again erotic works, were much in demand with wealthy patrons. So in some ways the French art world received a shock when Greuze’s pompously moralising rural dramas on canvas countered the frivolity of the artificial world of Rococo art.

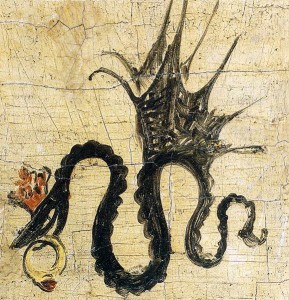

The featured painting today is entitled The Father’s Curse and The Punished Son which Greuze completed in 1778. The first thing that strikes one with the characters depicted at the bedside scene is their staged posturing. This was another trademark of Greuze, the way in which his characters were shown in dramatic poses that had once been reserved for grander historical and religious subjects. It reminds me somewhat of watching an amateur dramatic performance were all the actions of the amateur players seem so “over the top” and comically exaggerated.

The setting of today’s painting is the final part of a tragic tale. The beginning of this saga was when a son decided to abandon the family home and join the army despite the pleadings of his father, mother and siblings who need him to financially support the family. Not having been swayed by their entreaties he left. Now the scene is set with his homecoming. However, it is not a joyous celebration of the return of the prodigal son. Before us in the bed we see his ageing father who has just died and his family are all congregated around the death bed, inconsolable. Look at the exaggerated poses of the family members as they pour out their grief. In the right foreground we see the son who has returned to his home wounded. He is stooped and remorseful, racked with guilt, having returned too late to be with his father before he died and he can see by the state of the home that the family have little money and of course we see him, head in hand, realising it was all his fault.

The increasing significance of the middle class, and of middle-class morality, also played a part in the success of Greuze’s painting genre. His paintings seemed to preach the ordinary virtues of the simple life. It was a call to the return of honesty in the way we dealt with life. Surprisingly, the unconcealed melodrama of his pictorial sermonising was not found offensive, and visitors to the Salons were moved and often openly wept in front of his paintings. The intellectuals of the day were generally opposed to rococo art style and considered its style decadent, and in turn looked upon Greuze as “the painter of virtue, the rescuer of corrupted morality.” Greuze’s fashion for simplicity and his portrayal of ordinary people infiltrated even the highest circles of society, and engravings of Greuze’s work were popular with all classes of society.

Greuze’s reputation declined towards the end of his life and through the early part of the 19th century but briefly revived after 1850, when 18th-century painting returned to favour. The advent of modernism in the early decades of the 20th century totally obliterated Greuze’s reputation.

Greuze survived the French Revolution but his fame did not. He died in Paris on March 21, 1805, in poverty and obscurity.