My Daily Art Display featured artist today is the German Renaissance painter and designer of woodcuts, Lucas Cranach the Elder. He was born in Kronach a small German town in Upper Franconia, Bavaria in 1472. His adopted surname was a derivation of the name of his birthplace, which was a quite usual practice at the time. His father who had the unusual name of Hans Maler, the surname being the German word for “painter”. In those days it was also not uncommon for a person’s surname to have no connection with ancestors but to do with the person’s profession. Lucas Cranach’s father was indeed an artist, hence his surname. Little is known of Cranach’s early life or fledgling artistic training except that one of his tutor commented that Cranach had displayed his artistic talents whilst a teenager. It is recorded that Cranach arrived in Vienna in 1501 and stayed until 1504. It was during this period that he completed many of his earliest works such as The Crucifixion (1503) and Portrait Doctor Johann Stephan Reuss’s (1503). These and his other artistic works captured the attention of Duke Friedrich III, Elector of Saxony, known as Frederick the Wise who, in 1505, employed Cranach as a court painter at the palace of Wittenberg and although he took on private commissions, Cranach remained as court painter almost to the end of his life.

In 1508 Cranach married Barbara Brengbier and they were to have six children, four daughters and two sons. The most famous of the children was Lucas the Younger who went on to become a well known artist in his own right. At the court Cranach, along with other artists such as Dürer and Burgkmair painted many altarpieces for the castle church. In 1509 Cranach temporarily left the court at Wittenberg and went to the Netherlands and painted the portrait of Emperor Maximilian I and his eight year old young grandson Charles who would later become Emperor Charles V.

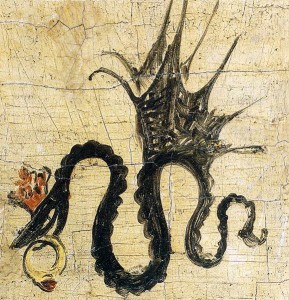

It is interesting to note that up until this time Lucas Cranach the Elder always signed his works with his initials “L C” but in 1508 the Elector of Saxony, Frederick the Wise knighted him and awarded him the coat of arms of a winged serpent as an emblem which, from that time on, superseded or was added to his initials on his paintings.

It is interesting to note that up until this time Lucas Cranach the Elder always signed his works with his initials “L C” but in 1508 the Elector of Saxony, Frederick the Wise knighted him and awarded him the coat of arms of a winged serpent as an emblem which, from that time on, superseded or was added to his initials on his paintings.

An example of this can be seen in his woodcarving of Adam and Eve which he completed in 1509.

Look at the note on the tree showing Cranach’s initials as well as the winged serpent. The coats of arms hanging from the branch to the left of the trunk are those of the Elector of Saxony

Cranach was a friend of Martin Luther, and his art expresses much of the character and emotion of the German Reformation. Cranach, through many of his paintings and engravings, championed the Protestant cause. His portraits of Protestant leaders, including the many portraits of Luther and Duke Henry of Saxony are solemn and thoughtful and painstakingly drawn. At this time Cranach had a large workshop and worked with great speed. His output of paintings and woodcuts was immense.

He died in Weimar, in 1553 aged 81. Cranach’s sons, Lucas and were both artists, but the only one to achieve distinction was Lucas Cranach the Younger, who was his father’s pupil and often his assistant. His oldest son Hans Cranach was also a promising artist but died prematurely.

My Daily Art Display featured painting today is a diptych, which is a picture or other work of art consisting of two equal-sized parts, facing one another like the pages of a book. It is entitled Portraits of Johann the Steadfast and Johann Friedrich the Magnanimous which he painted in 1509. They are usually small in size and hinged together. This one was painted by Lucas Cranach the Elder in 1531. It consists of two portraits. On the left hand panel of the diptych we have a portrait of Johann the Steadfast who was the Elector of Saxony following the death of Frederick the Wise in 1525. On the right hand side we have a portrait of Johann Friedrich the Magnanimous the eldest son of Johann the Steadfast and who became Elector of Saxony on the death of his father in 1533. Cranach was the court painter during the time both of these men were in power.

Looking at the left hand portrait of Johann the Steadfast we see him against a dark green background wearing a black coat with some sort of grey patterning. On his head he has a black hat highlighted with small pearl ornaments.

On the right hand panel we see the portrait of the six-year old, fair-haired boy, Johann Friedrich. Note how Cranach has reversed the colours in comparison to the left hand panel. Where we had a man in black with a green background, in this right hand panel, we have the young lad dressed in a green doublet with bands of red and white in what almost looks like a “tartan pattern” against a black background. The “slashed doublet” which was very fashionable in the first half of the 16th century reveals the red of the shirt which he wears underneath it. He too wears a hat, green in colour to match the doublet, on which are ornamental brooches and atop of which are multi-coloured ostrich plumes. In his hands we see him clutching hold of the golden pommel of a sword with his still-chubby little fingers.

It is unusual to see two men in a diptych which would normally hold portraits of a man and his wife. However there is some degree of poignancy about this coupling of father and son as the father lost his wife a couple of weeks after she gave birth to the young boy so we are looking at a widowed father and his motherless son.