Marie de Roode Heijermans

The artist I am looking at today is Catherine Mariam ‘Marie’ de Roode-Heijermans who was born in Rotterdam on October 14th, 1859. She was the daughter of Herman Heijermans, a journalist, and his wife Matilda Moses Spiers. She grew up in a large, liberal Jewish family in the Dutch city of Rotterdam. Marie was the second oldest of eleven children and the older sister of Herman a playwright, Louis a community physician, Ida a children’s pedagogue and Helena who was a school principal. Marie did not finish high school but was given drawing lessons from the Dutch painter, Suze Robertson.

She studied at the Koninklijke Academie van Beeldende Kunsten (Royal Academy of Art, The Hague) and Academie voor Beeldende Kunsten Academy of Visual Arts, Rotterdam. One of her teachers was Jan Philip Koelman. In 1881, aged 22, she obtained the drawing certificate at the Hague Drawing Academy. After leaving the Academy Marie worked as an art teacher for several years. Following this period as an educator she left for Brussels, where she took more art lessons at the studio of the French painter, Ernest Blanc Garin. Here, in the Life Clas, she was allowed to paint from nude models, something that was not yet allowed to women in the Netherlands.

Her crowning artistic achievement came in 1892 with her painting ‘Hospice des Vieillards which appeared at the Paris Salon in 1892 and following on from this Marie received a three-year working grant from the Belgian Queen Regent.

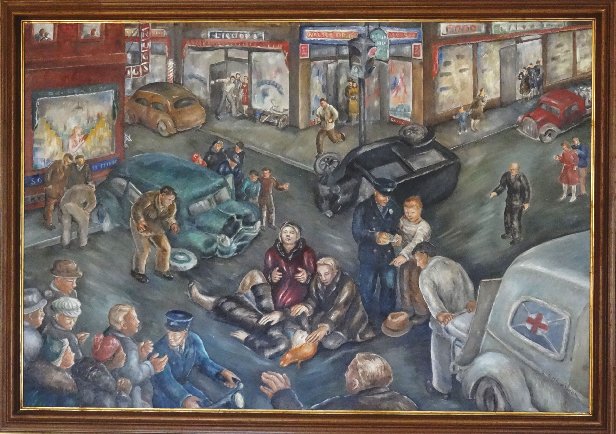

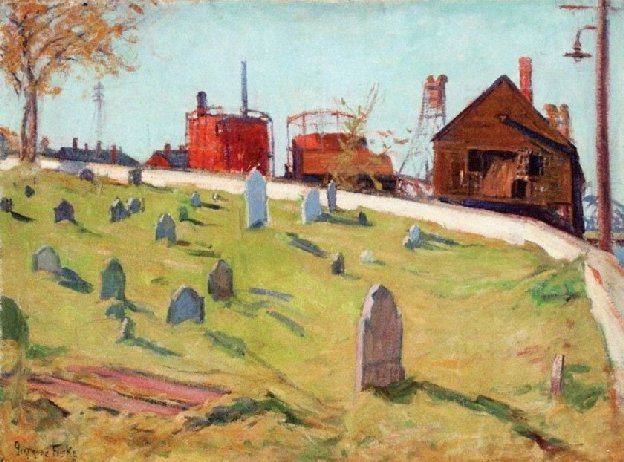

Victime de la misère (The Victim of Misery) by ‘Marie’ Heijermans (1897)

Five years later, in 1897, a piece of Marie’s artwork received more publicity but this time, for all the wrong reasons. The painting is now deemed to be the most outstanding works of the artist’s career. It was a depiction that focused upon social themes, which validates Marie’s artistic commitment to portray the difficult living conditions many people had to endure. The painting entitled Victime de la misère (The Victim of Misery) was exhibited at the World Exhibition in Brussels. King Leopold II of Belgium who saw it considered it to be deeply offensive. and soon after his visit to the exhibition it was removed. Marie Heijermans tried to force its reinstatement through the courts, but all her efforts were in vain.

In the late 1920s the work had been bought by the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam but the depiction was criticised by art critics. For them, this purchase by the museum was unacceoptable as the councilors had, in their eyes, believed the musum had spent tax-payer’s money unwisely. Following the bad press the work was relegated to the museum’s basement at the request of the councilors and the museum mitigated their decision stating “lack of space” forced them to do this.

So what was this furore about? What made the depiction offensive? Why hide it from public view? Why this censorship? Often paintings are censored for political or religious reasons, because the artists who created them desired to communicate through them, a message that upset certain governments and religious groups. However, there are other reasons for censorship such as paintings that affect morality and behaviour. Censorship in all its forms is a manifestation of the fears and tensions of a time when various groups attempt to prevent conversations and behaviours that are different from their own from spreading in society, and by doing so, believing that they can prevent social changes. However, this work by Heijermans did not hint at political or religious connotations.

The elderly “client”.

Maybe the title of the painting gives us a clue – Victime de la misère (The Victim of Misery). From these words we must deduce that the depiction will be somewhat harrowing and maybe it was believed that instead of exhibiting it for its artistic merit, it should be hidden away to avoid upsetting viewers and causing offence. The canvas had been hung for a month, but when the Belgian king was due to visit the exhibition, those in charge considered it to be too offensive and had it removed. Marie Heijermans tried unsuccessfully through the courts to have it reassigned to the gallery walls. However, the Belgian and Dutch authorities backed the gallery decision and declared the work to be a disgrace. Only one voice from the media defended Marie’s work and he was Jan de Roode in Het Volksdagblad, the first workers’ newspaper published in the Netherlands.

Top hat and the “payment” for services rendered.

So let us take a closer look at the depiction for clues. Before us we see a small room, with little furnishing, sparsely decorated with few objects. This could be described as a simple humble room without any luxuries. The painting shows a young naked girl sitting on a stool at the side of the bed. Surely that is not reason enough for it to be taken off the museum wall and hidden in the basement.

The Three Graces by Rubens (1638)

Numerous artists over the years have depicted naked young women in their works. They were depictions of goddesses, nymphs, and portrayed young women exhibiting themselves in seductive poses which for some men allowed them to fantasize and romanticize and what could be. These were looked upon as being acceptable due to the concept being mythological. So what makes this work by Heijermans suffer the wrath of the censors?

Olympia by Édouard Manet (1863)

Heijerman’s painting was not the first to fall foul of the censors for its depiction Édouard Manet’s 1863 famous painting Olympia, reworked the traditional theme of the female nude, using a strong, uncompromising technique. Both the subject matter and its depiction explain the scandal caused by this painting at the 1865 Salon. Nowadays the sight of the naked woman would not have caused a ripple of disgust, but we need to remember that it was painted in 1897 and moral standards were different in those days. The female nude outside those pre-established contexts of mythology was found unacceptable and deemed immoral, an viewed as an assault on good morals.

This painting depicted prostitution and for many this was an unacceptable reality of life and one which, like the painting itself, should be hidden from view. In the foreground we see the young woman sitting on a large, padded stool next to an empty bed which had just been slept in. Her head is bent downwards. She appears utterly miserable and so we refer to the paintings title – The Victim of Misery. The young woman appears to be from a low social class, and her nakedness and an unmade bed points towards her being a prostitute. Look at the end of the bed and next to the woman, we see a chair with some discarded clothes, the man’s top hat and a 20-franc note, the latter is probably the payment she received for her services. In the background, we see a distinguished elderly gentleman with his back to us, adjusting his cravat, dressing himself in a white shirt and black vest before a mirror and we can deduce he is from a very different societal class compared to that of the woman. He is her customer. There is a stark contrast between the satisfied air of the corpulent gentleman and the dejected look of the young woman.

Now collating this information, we can see what Marie Heijermans had depicted and what was her implied message to the viewers. She has through this poignant work denounced the fact that this woman (and many like her) were forced into prostitution. In case we were allowed to doubt the truth of what we are seeing Marie has given the work a title that does not allow us any doubt as to what should be apparent – that this young woman was a victim of prostitution and that society had failed her.

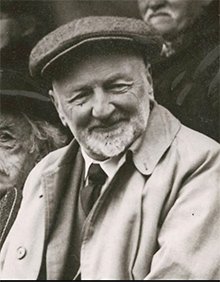

Justus Johannes de Roode

Marie Heijermans was a member of the Cercle des Femmes Peintres, a Brussels-based association of visual artists who were active between 1888 and 1893. On August 23rd 1899 she married the journalist Justus Jan de Roode, who later became editor of Het Volk, a Belgian newspaper that focused on “news with a human undertone”. He was also staff member of the International Labour Organization. The couple had no children. He had been one of the few people which denounced the removal of Marie’s censured painting.

In the years 1921-1926, the couple stayed in Geneva Switzerland, where De Roode was working for the Bureau International du Travail (BIT). Heijermans favoured subjects for her paintings were the elderly, nursing homes, hospices and workers. In 1999-2000, the Marie Heijerman’s painting, – Victime de la misère (The Victim of Misery), was included in the exhibition featuring women artists, As you Will: Women artists in Belgium and The Netherlands (1500-1950). This travelling exhibition was held at the Koninklijk Museum voor Schone in Antwerp and the Museum voor Moderne Kunst in Arnhem. In 2002, the painting featured in the Amsterdam Historical Museum exhibition, Love for Sale, which documented four centuries of prostitution in Amsterdam. The exhibition brought together many amazing documents, photographs and paintings about prostitution. Heijerman’s Victime de la misère was said to be one of the highlights of the exhibition. In 2014 it was exhibited again, this time at the Stedelijk, in the exhibition Men for Women, 5 Centuries of Art, an exhibition which challenged the notion that women were largely absent from art before the late 1800s.

Heijermans died in Amsterdam on October 26th 1937, aged 78. Her husband Justus Johannes de Roode died on January 14th 1945, three weeks before his 79th birthday.

Below are some of the websites where I was able to get information for this blog.