Some time ago I talked about Madonna and Child genre of paintings and said that I believed that, as far as religious paintings were concerned, they were the most prolific type of religious art throughout the ages. Other highly popular religious concepts in paintings are the Pietà and the Lamentation.

The Lamentation represents a particular moment from Christ’s Passion, between the Deposition (the bringing down of the lifeless body of Jesus Christ from the cross after the crucifixion) and the Entombment. The paintings always show groups of grieving mourners gathered around the central figure of Christ and his mother, the Virgin Mary. They often appeared in narrative paintings of the Passion of Jesus Christ.

The term Pieta derives from the Italian word for pity. The Pietà is a timeless image, and is a term applied to a painting or sculpture which usually just depicts the Virgin Mary and the dead Christ, often with the Virgin Mary supporting the body of Christ on her lap. However, sometimes the characters of St John the Evangelist or Mary Magdalene would be added to the scene. The setting does not depict a particular moment in the Passion story, unlike scenes of the Lamentation.

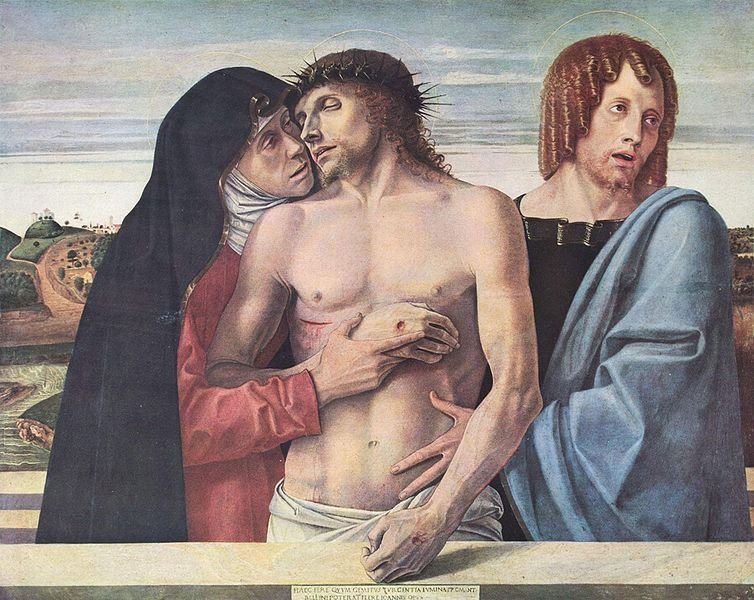

So is My Daily Art Display today a Pietà or a Lamentation? It is entitled a pietà so who am I to disagree ! It is tempera on panel painting which I came across this week and which I thought was very heartrending and poignant. One could almost feel the grief of the Virgin Mary and St John the Evangelist. The work of art painted in 1460 and entitled Dead Christ Supported by the Madonna and St John; (Pietàa) is by Giovanni Bellini and can be seen at the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan.

At the bottom of the painting, on the parapet is the inscription:

HAEC FERE QUUM GEMITUS TURGENTIA LUMINA PROMANT: BELLINI POTERAT FLERE IOANNIS OPUS

which translated means:

When these swelling eyes evoke groans, this work of Giovanni Bellini could shed tears

To me, this perfectly sums up the painting. It is not just me that is moved by this painting as it has been rightly considered as one of the most moving paintings in the history of art. There is a deep passionate feeling to this painting. It is not just religious passion but human and psychological passion. Look at the Virgin Mary as she looks into the eyes of her dead son. See how she is almost using his shoulder to support her chin. There is a deep hurt and sorrow in her eyes as she looks intently at the face of her lifeless son. Is there anything more moving that a mother’s sorrow for the loss of her only son? She clutches the right wrist of Jesus and holds his lifeless limb across his chest. She is almost cuddling him wishing she could breathe life into his dead body. We can see the wound on the back of his right hand made by the crucifixion and Jesus’s left hand, with his fingers curled closed in pain, rests on the parapet.

To the right we see Saint John the Evangelist’s with his face wracked with sorrow and one can empathise with his desolation. His head is turned away from Mary and Jesus as if he can no longer bear to look at the grieving mother clutching at her dead son. John’s mouth is open as if he is crying out in anguish. Maybe he is begging for some morsel of comfort. It is as if he is asking for help to endure what is before him, as he is aware of his task ahead, that of consoling Mary.

The three figures are in a tight group in the foreground behind which is an infinite horizon. The sky is a steely grey-blue which gives a feeling of cold and accentuates the pervading anguish of the setting.

This is indeed a very sad and moving painting.