Louise at work (c.1930)

My featured artist today is Louise Emerson Rönnebeck, the twentieth century painter famous for her murals. Louise Emerson was born on August 25th 1901 in the Philadelphia suburb of Germantown but spent her childhood in New York. She was the third child of Mary Crawford Suplee and Harrington Emerson and had two elder sisters, Isabel Mary and Margaret Eleanor. Her father was the son of Edwin Emerson, a Professor of Political science and was an American efficiency engineer and business theorist, who founded the management consultancy firm, the Emerson Institute, in New York City in 1900.

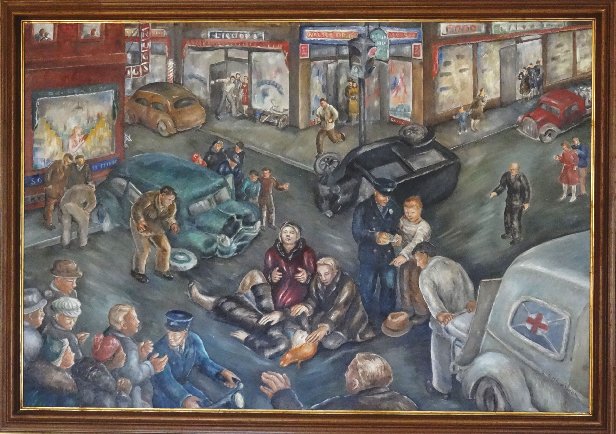

Car Accident at Aylard’s Corner (Denver) by Louise Emerson Rönnebeck ( 1937)

Having completed her regular schooling she attended Barnard College, Columbia University, which was then a private women’s liberal arts college in the New York City borough of Manhattan. In 1922 Louise Emerson graduated from Barnard College and, for the next three years, went on to study at the Art Students League of New York where she studied life drawing and anatomy with Canadian American painter, George Bridgman, sculpture with Leo Lentelli, the Italian sculptor and painting with Kenneth Hayes Miller. The latter had the greatest influence on her art and future career. Miller who taught at the Art Students League from 1911 until 1951 had among his students Edward Hopper and George Bellows.

Building Boom by Louise Emerson Rönnebeck (1937)

During the summers of 1923 and 1924 Louise travelled to France and studied fresco painting at the Fontainebleau Schools which had been established in 1921. It was situated in Fontainebleau, thirty-five miles south-east of the centre of the French capital and consisted of two schools: The American Conservatory, and the School of Fine Arts. Here she studied under Paul-Albert Baudouin, a painter of genre, landscapes and decorative panels.

Taos Indian Child by Louise Emerson Rönnebeck (1925)

In the Summer of 1925, Louise did not carry on with her tradition of going to Paris to study at the American Conservatory and School of Fine Arts as she and her sister Isabel had been invited to stay at Taos in the New Mexico ranch home, Los Gallos, belonging to Mable Dodge Luhan. The ranch was located near the eastern edge of the town center of Taos. Luhan, the heiress of Charles Ganson, a wealthy banker, was an American patron of the arts, who was particularly associated with the Taos art colony. The ranch was a meeting place for many contemporary artists and writers and Louise Emerson distinctly remembered her visit there:

“…It was a marvellous place, all wild, strange, empty and romantic…”

Mabel Dodge Luhan Ranch House

Other guests at the ranch at the time were the writers D.H. Lawrence and his wife Frieda along with Aldous Huxley. Louise was a great admirer of Lawrence and so she and her sister decided to call on him, albeit they had not been invited by the writer. Louise remembers that visit well. Despite not having been invited, it was perfectly all right. He seemed only too happy to have someone who would listen to him. She remembered that he had a red beard and deep-set eyes which conveyed a surprising intensity. She said she was impressed with this wiry, frail, yet madly gifted person, who talked in a common, ugly voice. He and his wife Frieda seemed very Bohemian and avant-garde. Lawrence fought with his wife and they shouted at each other. Despite looking very ill, he baked his visitors bread, and Frieda made jam. Sensing she had been in the presence of a genius, it remained, as Louise recalled, that it had been one of the most memorable days of my life.

Roberta by Louise Emerson Rönnebeck (1928)

Another of the guests staying at the Taos ranch was Arnold Rönnebeck. He was a German-born American modernist artist and sculptor who had arrived in America two years earlier. He was a good friend of many of the avant-garde writers and artists he had met during his time in Berlin and Paris. In America he had become friends with artist Georgia O’Keefe and photographer Alfred Stieglitz and it was at one of the latter’s gallery, An American Place that Rönnebeck first exhibited some of his artwork in America. The gallery was on the seventeenth floor of a newly constructed skyscraper on Madison Avenue. Arnold was impressed by Louise and wrote about her to his New York friend Stieglitz about his first impressions of this young woman:

“…What a summer! …. The one other person who is doing something about this country is a young girl from New York, Louise Emerson, a pupil of Kenneth Hayes Miller at the league. Still under the influence of Derain, but strong and powerful and with a very personal vision. She lives in one of Mabel’s cottages and is going very good watercolors and oil landscapes…”

Louise and Arnold Rönnebeck’s Wedding Photograph

Soon the friendship between Louise and Rönnebeck turned into love and in New York City, twenty-five-year-old Louise Emerson and Arnold Rönnebeck married despite him being sixteen years older than her. The marriage took place in March 1926 at the All Angels Episcopal Church on the Upper Westside of Manhattan and the reception after the ceremony took place in Louise’s parent’s home close by. Despite her marriage, Louise continued to use her maiden name professionally until 1931.

Arnold Rönnebeck working on his sculpture “Grief” in Omaha, Nebraska (1926)

The couple took an extended honeymoon travelling to Omaha, Santa Fe, and Los Angeles, places which Rönnebeck had to visit to finalise some painting and sculptural commissions and attend the one-man exhibitions of his work in San Diego and Los Angeles . After the honeymoon the couple settled in Denver where Arnold became director of the Denver Art Museum.

Louise with her son Arnold (1927)

Louise Ronnebeck gave birth to their first child, Arnold Emerson, in 1927 and two years later a second child Anna Maria Ursula was born. The Rönnebeck household with two young children and two working artists was somewhat chaotic and Louise had to balance looking after the family and carrying on with her art. Add to this mix, Louise was just starting her artistic career whereas her husband had passed the high-point of his career and since he arrived in America from Germany he had not reached the level of his European fame. Her struggle to manage all her tasks and family duties was highlighted in a 1946 Denver Post article, in which Louise was described as:

“…a four handed woman – – managing home and children on one side, and teaching and painting on the other…”

In letters and interviews Louise talked about the struggle to have time to be a mother, wife and artist. In a letter to Edward B Rowan, a friend and arts administrator, teacher, artist, writer, lecturer, critic, and gallerist, dated February 1938, she wrote:

“…Being mother of two strenuous children, and the caretaker of a fairly large house, I have to budget my time carefully…”

“… Between the children’s meal time, the mother rests while the artist works…”

Louise Emerson Rönnebeck

In a February 1930 article in the daily newspaper, Rocky Mountain News, entitled Denverite Out to Prove She Can be Mother and Artist by Margaret Smith, Louise was quoted as saying that she would never encourage her children to become artists as an artist’s life is both unsocial and confining. Although her husband missed the big city lifestyle, Louise was content with her new life in Denver and in a 1934 letter to her former teacher, Kenneth Hayes Miller, she wrote:

“…I have become very attached to life in the west. We rent a charming really spacious house almost in the country for very little money, take frequent weekends in the mountains, and the children are radiant and adorable persons. Arnold, however, misses bitterly the stimulation of a big city and longs very much for a change…”

Colorado Minescape by Louise Emerson Rönnerbeck (c.1933)

Louise and Arnold had only been living in Denver for three years when the country was hit by the Great Depression and Louise knew that with their finances being in a poor state she and the family needed some help to survive. She turned to the WPA. The WPA was the Works Progress Administration, later known as the Work Projects Administration. This was an American New Deal agency that employed millions of jobseekers to carry out public works projects. The Federal Art Project was one of the five projects sponsored by the WPA, and the largest of the New Deal art projects. It was not solely created as some cultural activity, but as an assistance measure which would lead to artists and artisans being employed to create murals, easel paintings, sculpture, graphic art, posters, photography, theatre scenic design, and arts and crafts. One of the important things for the artists, besides earning money, was that commissions were essentially free of government pressure to control subject matter, interpretation, or style.

……….to be continued.

I collected information regarding the life and art of Louise Emerson Rönnerbeck from various sources. The main ones were: