Thérèse Schwartze – self portrait (1917)

Therese Schwartze was a Dutch 20th century painter. Such was a hugely talented portrait artist that was one of only a few females who had been honoured by receiving an invitation to contribute her self-portrait to the hall of painters at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. This genius of portraiture completed around a thousand works during her forty-year career, which means that she completed more than twenty paintings a year. Because many of her portraits were created to be treasured by family members, most of her work has remained in private collections. About one hundred and fifteen of her paintings are in public collections in the Netherlands, and twelve are part of foreign public collections, which leaves the locations of nearly four hundred paintings still unknown. She became a millionaire in the process. Schwartze also established an international reputation, with countless exhibitions and commissions throughout Europe and the United States.

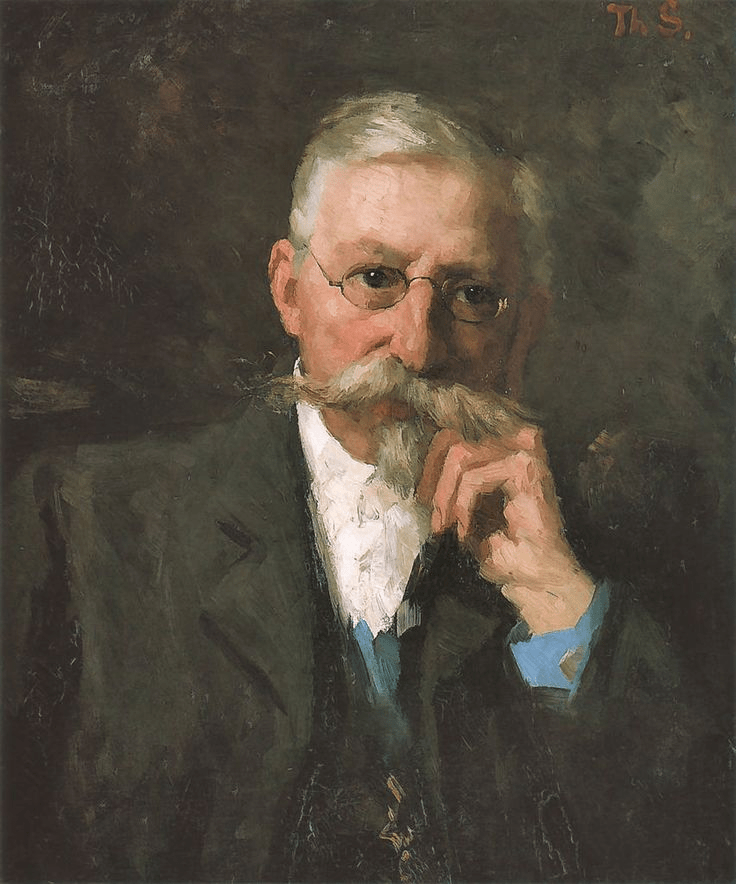

Self Portrait by Johan Georg Schwartze

Thérèse was born on December 20th 1852 in Amsterdam. She was the daughter of Johan Georg Schwartze and Maria Elisabeth Therese Herrmann. She was one of five children and had four sisters including Georgine, a sculptor, Clara Theresia, a painter and one brother, George Washington Schwartze, also a painter.

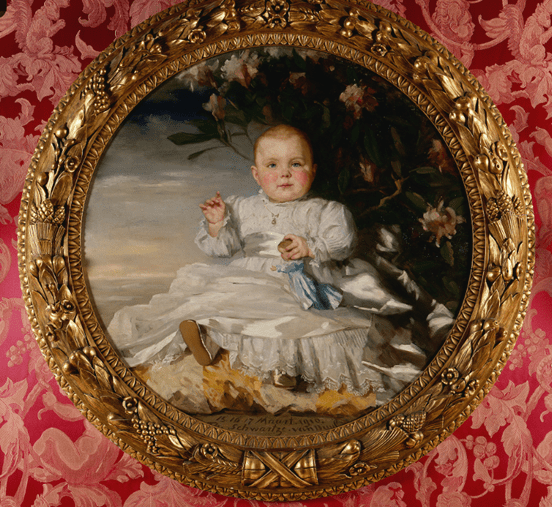

Portrait of Thérèse aged 16 by her father, Johan Georg Schwartze (1869)

Her father was a well-respected portrait painter and it was he who provided Thérèse with her first artistic training. In 1869 her father completed a portrait of his daughter, Thérèse.

Three girls of the orphanage in Amsterdam by Thérèse Schwartze (1885)

At that time, there was the perception that teaching girls and young ladies to paint was seen simply as a part of a cultured upbringing rather than a profession for earning money which was viewed as the role of the man. But for Johann Schwartze he couldn’t care less about such conventions. He trained his daughter in painting and drawing from a very young age and intended that Thérèse would become his worthy successor. She started her professional career at the age of sixteen, working in her father’s studio which she eventually took over when she was twenty-one after his death in 1874. Schwartze wrote to her father in a birthday letter, writing:

“…I will apply myself more to everything, so as, with God’s blessing, to be able to earn my living by painting…”

Because the art academies were not yet open to girls, her father sent her to Munich for expensive private lessons for a year under Gabriel Max and Franz von Lenbach who was regarded as the leading German portraitist of his era. In 1879 she moved to Paris and continued her artistic studies under Jean-Jacques Henner, the Alsace-born portrait artist.

The Vasari Corridor at the Uffizi Gallery, Florence

Thérèse Schwartze’s portraits are truly remarkable and she was one of the few women painters, who had been honoured by an invitation to contribute her self-portrait to the Hall of Painters, the Vasari Corridor, at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. The Uffizi collection is one of the most complete in all Europe, first started by Cardinal Leopoldo de’ Medici in the 17th century. The passageway was designed and built in 1564 by Giorgio Vasari to allow Cosimo de’ Medici and other Florentine elite to walk safely through the city, from the seat of power in Palazzo Vecchio to their private residence, Palazzo Pitti. The passageway used to contain over a thousand paintings, dating from the 17th and 18th centuries, including the largest and very important collection of self-portraits by some of the most famous masters of painting from the 16th to the 20th century, including Filippo Lippi, Rembrandt, Velazquez, Delacroix and Ensor. While the Medici family bought the first paintings, after the collection started, the family started receiving the paintings as donations from the painters themselves. This has continued over the centuries and there were more paintings in the collection that did not have space to be exposed. Things have now changed as from 1973 to 2016, some of the self-portraits which had been hung in the Vasari Corridor, were, however only visible during restricted and occasional visits because of the confined space, which, also lacked air conditioning and adequate lighting. Most of the self portraits have been moved to other rooms at the Uffizi.

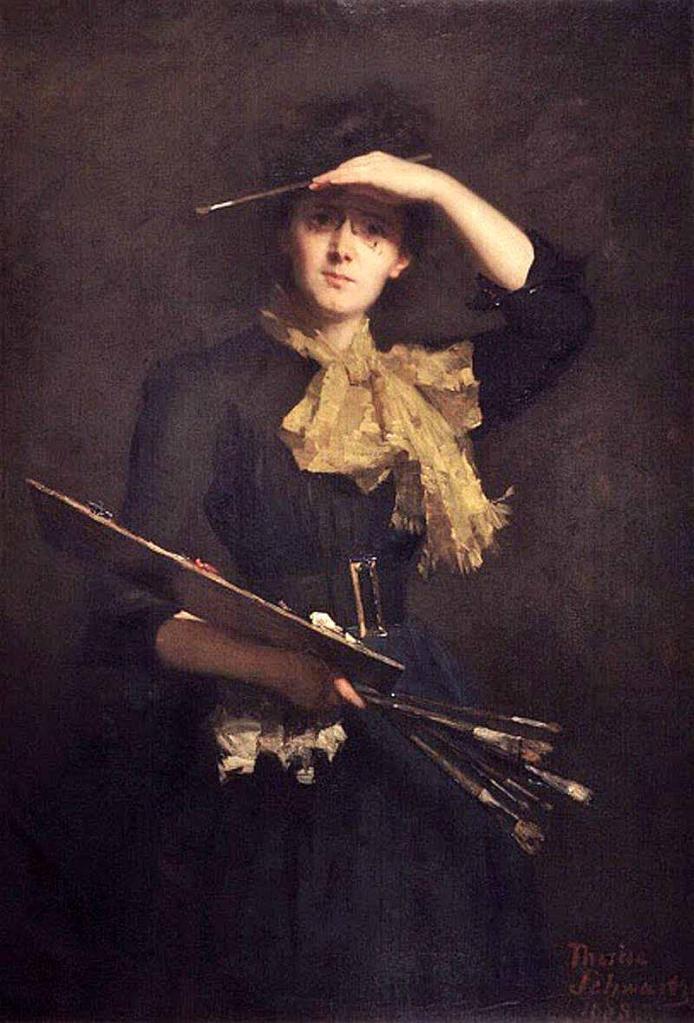

Self-portrait with Palette by Thérèse Scwartze (1888)

Only a handful of female portrait painters were active professionally in the 19th century, one of whom was Schwartze, who was nicknamed the ‘Queen of Dutch Painting’. In the self portrait she contributed to the Uffizi entitled Self-portrait with Palette, she depicts herself staring out at us with a haunted look, paintbrush in one hand with the other looped through a paint-laden palette. The background of this canvas is bare, and our eyes are drawn to the painter’s tools: eyes, brush, pigments, and a rag at the ready. The painting was exhibited at the 1888 Paris Salon before being given to the Uffizi gallery in Florence.

Sir Joshua Reynolds self portrait (c.1748)

Thérèse’s depiction of herself in her self-portrait could well have been inspired by Sir Joshua Reynold’s self-portrait which shows him similarly with his hand raised shielding his eyes from the bright light.

Young Italian Woman, with ‘Puck’ the Dog by Thérèse Schwartze, c. 1885)

Whilst living and studying in Paris, Thérèse completed her painting, Young Italian Woman, with ‘Puck’ the Dog. The model she used for this painting was known as Fortunata. She was one of the many professional Italian models working in Paris in the late 19th century. Schwartze started this painting in 1884 and exhibited it a year later in Amsterdam, having added the dog in the meanwhile.

According the 2021 biography by Cora Hollema and Pieternel Kouwenhoven entitled Thérèse Schwartze: painting for a living. Thérèse’s career took off at a time when a new, wealthy Dutch class wanted to flaunt its status and what better way to achieve this than with a flattering portrait. Her biographer wrote:

“She was in demand because she produced a new elegant, un-Dutch, extravagant, flattering style of portraiture which was in demand by the upcoming ‘new money…….. The new entrepreneurs and industrialists in the second half of the 19th century…”

Portrait of Aleida Gijsberta van Ogtrop-Hanlo with her five children by Thérèse Schwartze (1906).

Schwartze was one of the leading society painters in the Netherlands around 1900. Her clientele came from the nobility and the bourgeois elite in Amsterdam and The Hague. Members of the royal family also sat for her. A good example of her excellent portraiture is her 1906 group portrait of Aleida Gijsberta van Ogtrop-Hanlo with her five children. In this work, Aleida van Ogtrop-Hanlo is surrounded by, from left to right: Adriënne (Zus), Pieter (Piet), Maria (Misel), Eugènie (Toetie) and Adèle (Kees). The youngest and sixth child, Joanna (Jennie) was not yet born. Her husband was a wealthy stockbroker and founder of Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw. The portrait of his wife and children has a dreamy quality, with rich clothing and poetic colours. It gives an excellent impression of the self-image of the Dutch upper classes at the beginning of the twentieth century. Stylistically Thérèse Schwartze followed in the footsteps of the famous eighteenth-century English portrait painter, Thomas Gainsborough.

Portrait of the six Boissevain daughters by Thérèse Schwartze (1916)

An equally great group portrait by Thérèse Schwartze was her Boissevinfamily portrait but this a more decorous depiction. It is entitled Portrait of the Six Boissevain Daughters and she completed it in 1916. According to Schwartze’s biography by art historian, Cora Hollema, this difference in style was not due to a development of the artist, but more to do with the wishes of her client. Mr. & Mrs. Boissevain, who were wealthy members of the Amsterdam upper class had ten children, six daughters and four sons. They were aware of the portrait of Aleida and her children by Thérèse but believed it to be far too modern. So, when they commissioned Thérèse to paint the portrait in 1916 they asked her to produce a more time-honoured portrait of their daughters. Thérèse was now the breadwinner of the family and so sensibly adapted her style according to her client’s demands bearing in mind the adage: The client was king.

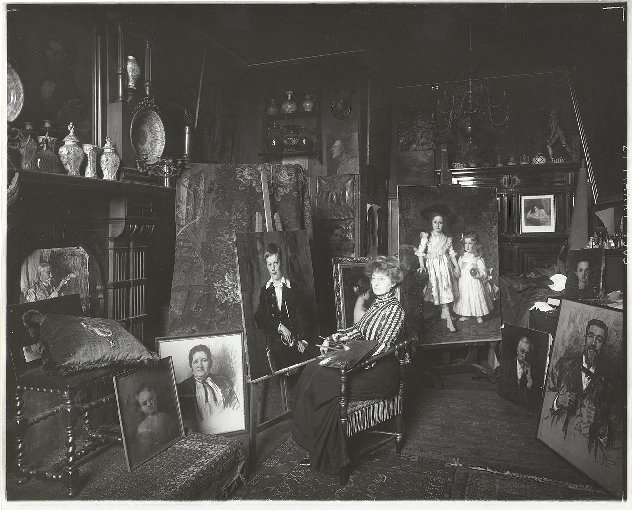

Thérèse Schwartze in her studio, Prinsengracht 1021, Amsterdam, 1903.

Thérèse’s great success as an artist became a point of reference for the young Dutch women painters who founded the Amsterdamse Joffers, a group of women artists who met weekly in Amsterdam at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. These “ladies of Amsterdam” met weekly, often at the Schwartze home, to update the glorious Dutch tradition of painting based on French Impressionist innovations. They supported each other in their professional careers. Most of them were students of the Rijksakademie van beeldende kunsten and belonged to the movement of the Amsterdam Impressionists.

Woman wearing a hat (Portrait of Theresia Ansingh (Sorella)), by Thérèse Schwartze (after 1906).

Besides Schwartze’s commissioned portraits, which made her very wealthy, she still had time to complete portraits of her friends and relatives which were not commissioned and were often given as gifts. A fine example in this regard is the portrait of Schwartze’s niece, Theresia Ansingh, who later became a member of the Amsterdam school of female painters known as The Joffers, many of them were inspired by Schwartze’s professional success.

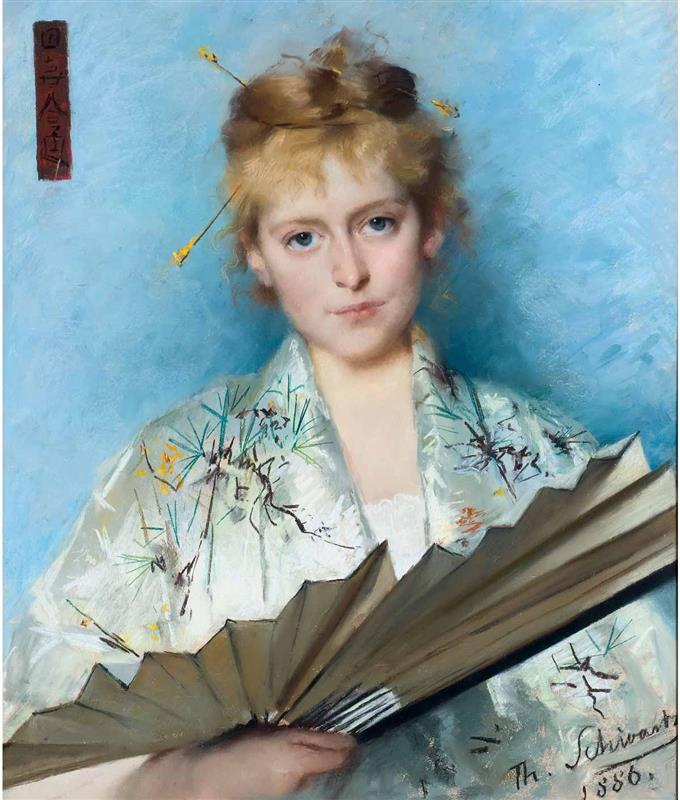

Maria Catharina Ursula (Mia) Cuypers by Thérèse Schwartze (1886)

One of my favourite portraits by Schwartze was her fascinating portrait of one of her friends, which is an amalgam of formal and informal portraiture and is entitled Portrait of Mia Cuypers. She was a daughter of the architect Pierre Cuypers, who designed such famous buildings as the Rijksmuseum and Amsterdam’s Central Station. In 1883, she fell in love, to the dismay of her family and the astonishment of “high society,” with the Chinese-British merchant Frederick Taen-Err Toung from Berlin, who was in Amsterdam selling his Oriental merchandise at the International Colonial Exposition. Mia managed to overcome the social uproar and married Toung in 1886. Being a close acquaintance of the Cuypers family, Thérèse was commissioned by the groom-to-be to make this wedding portrait, which is said to have only taken her one and a half days to complete. There are Chinese characters in the upper left corner, which are not clear in my attached photo, which mean “rice field,” “longevity”/”delighted,” and “coming together.”

Portrait of Queen Emma by Thérèsa Schwartze (ca. 1881)

Soon after, she received a commission for a portrait of Queen Emma and the little princess Wilhelmina, who was born in 1880. In the single portrait of the young queen, she is dressed in dark colours against a neutral background, all is dark except her face. In this painting, one can already see the fine art of portraiture and the depicting of differing textures that Thérèse fully mastered. The fur stole, the lace cap on her head, as well as the brocade of the queen’s robe.

Portrait of Princess Juliana by Thérèsa Schwartze (1910)

Thérèse’s worked with the royal family of the Netherlands through a period of thirty-five years and in all they gave her six commissions that contributed greatly towards her fame and wealth. Most royal portraits were of Queen Wilhelmina.

Portrait of Queen Wilhelmina by Thérèse Schwartze (1910)

The royal court had a habit of paying a little more than the average client, which meant that 1910 was a particularly profitable year for Thérèse. She painted so many members of the royal family that she was almost deemed a member of their household.

Portrait of Anton van Duyl by Thérèse Schwartze

In 1906, Thérèse Schwartze married the editor-in-chief of the Algemeen Handelsblad, Anton van Duyl. Twelve years after they married, Thérèse’s husband died on July 22nd 1918. It was double blow for Thérèse as she herself had been very ill at the time and five months later, on December 23rd 1918, three days after her sixty-seventh birthday, she died in Amsterdam.

Grave of Thérèse Schwartze at the Nieuwe Ooster cemetery, Amsterdam.

She was buried at Zorgvlied cemetery in Amsterdam but was later reburied at the Nieuwe Ooster cemetery in Amsterdam, where her sister created a memorial to her, modelled after her death mask, which is now a rijksmonument.